« back

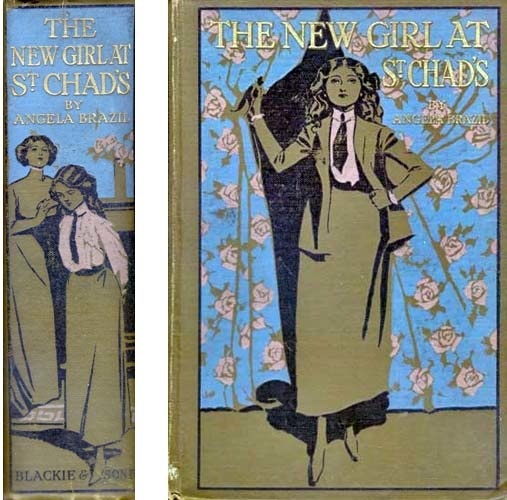

The New Girl at St. Chad's

A Story of School Life

By

ANGELA BRAZIL

Author of

"A Fourth Form Friendship" "The Manor House School"

"The Nicest Girl in the School" &c.

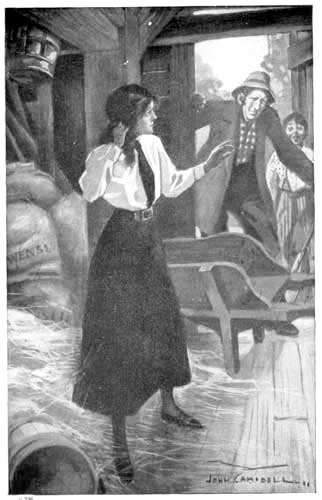

ILLUSTRATED BY JOHN CAMPBELL

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

1912

Contents

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | Honor Introduces Herself | 9 |

| II. | Honor's Home | 25 |

| III. | The Wearing of the Green | 39 |

| IV. | Janie's Charge | 57 |

| V. | A Riding Lesson | 75 |

| VI. | The Lower Third | 93 |

| VII. | St. Chad's Celebrates an Occasion | 106 |

| VIII. | A Mysterious Happening | 126 |

| IX. | Diamond cut Diamond | 138 |

| X. | Honor Finds Favour | 150 |

| XI. | A Relapse | 166 |

| XII. | St. Kolgan's Abbey | 182 |

| XIII. | Miss Maitland's Window | 199 |

| XIV. | A Stolen Meeting | 212 |

| XV. | Sent to Coventry | 227 |

| XVI. | A Rash Step | 243 |

| XVII. | Janie turns Detective | 258 |

| XVIII. | The End of the Term | 271 |

Illustrations

| Page | |

| A Chance for Retaliation | Frontispiece 146 |

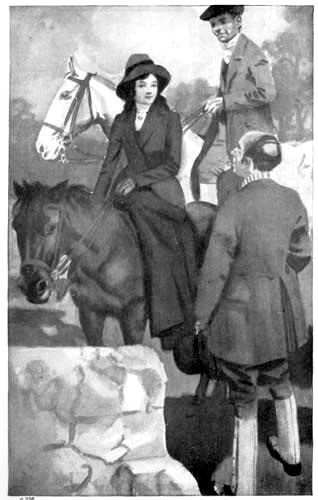

| Honor Concludes the Purchase of Firefly | 33 |

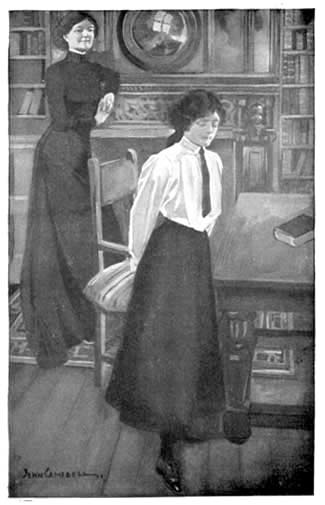

| An Interview With Miss Cavendish | 54 |

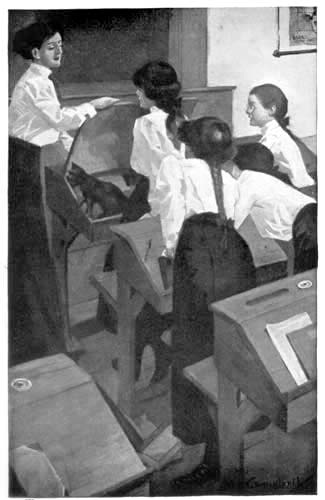

| The Liberation of Pete | 96 |

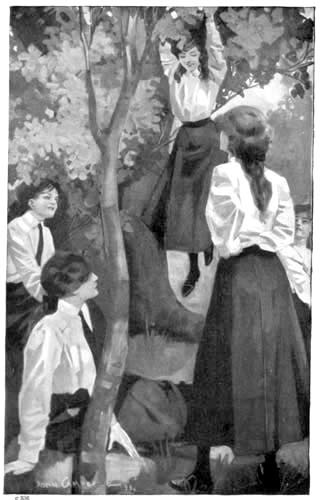

| An Unlucky Escapade | 209 |

| "Startled by the voices, she jumped up" | 253 |

Transcriber's Note: This sentence is incomplete, as printed:

"Where did you get it, Flossie?" enquired

THE NEW GIRL AT ST. CHAD'S

CHAPTER I

Honor Introduces Herself

"Any new girls?"

It was Madge Summers who asked the question, seated on the right-hand corner of Maisie Talbot's bed, munching caramels. It was a very small bed, but at that moment it managed to accommodate no less than seven of Maisie's most particular friends, who were closely watching the progress of her unpacking, and discussing the latest school news, interspersed with remarks on her belongings.

Maisie extricated herself from the depths of her box, and handed a pile of stockings to Lettice, her younger sister.

"What's the use of asking me?" she replied. "Our cab only drove up half an hour ago. I feel almost new myself yet."

"So do I, and horribly in the blues too," said Pauline Reynolds. "It's always a wrench to leave home. I'm perfectly miserable for at least three days at the beginning of each term. I feel as if——"

"Oh, don't all begin to expatiate about your feelings!" broke in Chatty Burns. "We know Pauline's symptoms only too well: the first day she shows aggressively red eyes and a damp pocket-handkerchief; the second day she writes lengthy letters home, begging to be allowed to return immediately and have lessons with a private governess; the third day she wanders about, trying to get sympathy from anyone who is weak-minded enough to listen to her, till in desperation somebody drags her into the playground, and makes her have a round at hockey. That cheers her up, and she begins to think life isn't quite such a desert. By the fourth morning she has recovered her spirits, and come to the conclusion that Chessington College is a very decent kind of place; and she begins to be alarmed lest her mother, on the strength of the pathetic letter, should have decided to let her leave at once, and should have already engaged a private governess."

"You're most unsympathetic, Chatty!" said Pauline, smiling in spite of herself. "You don't know what it is to be home-sick."

"I wouldn't parade such a woebegone face, whatever might be the depths of my misery," returned Chatty briskly.

"I'm always glad to come back," declared Dorothy Arkwright. "I like school. It's fun to meet everybody again, and arrange about cricket, and the Debating Society, and the Natural History Club. There's so much going on at St. Chad's."

"No one has answered my question yet," remarked Madge Summers. "Are there any new girls?"

Chatty wriggled herself into a more comfortable position between Adeline Vaughan and Ruth Latimer.

"I think there are about a dozen altogether. Vivian Holmes says there are four at St. Bride's, three at St. Aldwyth's, two at the School House, and two at St. Hilary's. I saw one of them arriving at the same time as I did, and Miss Cavendish was gushing over another in the library; and Marian Spencer has brought a sister—she introduced her to me just now."

"But what about St. Chad's?"

"We've only one, I believe, though Flossie Taylor, the Hammond-Smiths' cousin, has moved here from St. Bride's. She was always destined for a Chaddite, you know, only there wasn't room for her till the Richardsons left."

"She's no great acquisition," said Dorothy Arkwright. "I hate girls to change their quarters. When once they start at a house, they ought to stick to it."

"Well, she wants to be with her cousins, I suppose," put in Madge Summers. "Who's our new girl?"

"I don't know. I haven't heard anything about her."

"Perhaps she hasn't arrived yet."

"Sh! Sh!" said Pauline Reynolds, squeezing Madge's arm by way of remonstrance, and pointing to the closely-drawn curtains of the cubicle at the farther end of the room. "She's here now."

"Where?"

"There, you goose!"

"What has she shut herself up like that for?"

"How should I know?"

"Perhaps she's unpacking," suggested Dorothy Arkwright.

"If she is, she'll finish it quicker than Lettice and I can," returned Maisie Talbot. "Why can't you be hanging up some of those skirts, instead of sitting staring at me? Yes, this is a whole box of Edinburgh rock, but you shan't have a single piece, any of you, unless you get off my bed at once."

"Poor old Maisie, don't grow excited!" murmured Ruth Latimer, appropriating the box and handing it round, though no one attempted to move.

"But look here! what about this new girl?" persisted Madge. "Hasn't anybody seen her?"

"No. She's been in there ever since she arrived."

"Don't talk so loud; she'll hear you."

"I don't care if she does."

"I want to know what she's doing."

"I can tell you, then," said Chatty Burns, in a whisper that was more audible by far than her ordinary voice.

"What?"

"Crying! New girls always cry, and some old ones too, if you take Pauline as a specimen."

"I'm not crying now!" protested Pauline indignantly. "And how can you tell that the new girl is?"

"I'm as certain as if I'd proved a proposition in Euclid. Why should she have drawn her curtains so closely? If she's not lying on her bed, with a clean pocket-handkerchief to her eyes, I'll give you six caramels in exchange for three peppermint creams!"

"Then you're just mistaken!" cried a voice from the end cubicle. The chintz curtain was pulled aside, and out marched a figure with so jaunty an air as to banish utterly the idea of possible homesickness or tears.

It was a girl of about fifteen, a remarkably pretty girl (so her schoolmates decided, without an instant's hesitation), and rather out of the common. She had a clear, olive complexion, a lovely colour in her cheeks, a bewitching pair of dimples, and a perfect colt's mane of thick, curly, brown hair. Perhaps her nose was a little too tip-tilted, and her mouth a trifle too wide for absolute beauty; but she showed such a nice row of even, white teeth when she laughed that one could overlook the latter deficiency. Her eyes were beyond praise, large and grey, with a dark line round the iris, and shaded by long lashes; and they were so soft, and wistful, and winning, and yet so twinkling and full of fun, that they seemed as if they could compel admiration, and make friends with their first glance. The girl walked across the room in an easy, confident fashion, and stood, with a broad smile on her face, beaming at the seven others seated on Maisie's bed.

"Why shouldn't I pull my curtains?" she asked. "If I'd been pulling faces, now, you might have had some cause for complaint. You look rather a nice set; I think I'm going to like you."

The girls were so surprised that they could only stare. It seemed reversing the usual order of things for a new-comer, who ought to be shy and confused, to be so absolutely and entirely self-possessed, and to pass judgment with such calm assurance upon these old members of St. Chad's, some of whom were already in their third year at Chessington College.

"Perhaps I'd better introduce myself," continued the stranger. "My name is Honor Fitzgerald, and I come from Kilmore, near Ballycroghan, in County Kerry."

"Then you're Irish!" gasped Chatty Burns.

"Quite right. First class for geography! County Kerry is exactly in the bottom left-hand corner of the map of Ireland. It's a more hospitable place than this is. I've been here nearly two hours, and nobody has offered me any refreshments yet. I'm simply starving!"

She looked so humorously and suggestively at the Edinburgh rock that Madge Summers promptly offered it to her, regardless of the fact that the box belonged to Maisie Talbot.

"Come along here," said Ruth Latimer, trying to make a place for the new girl on the bed by pushing the others vigorously nearer the end.

"No room unless I sit on your knee, while you get up and walk about," declared Honor. "There! I knew you would!" as Madge Summers fell with a crash on to the floor.

"Seven little schoolgirls, eating sugar sticks;

One tumbled overboard, and then there were six!"

"Thank you. I think I prefer to 'take the chair', as the dentist says. There only seems to be one in each cubicle, but as I'm the visitor——"

"Take care!" screamed Maisie. "My clean blouses!"

"What am I doing? I declare, I never saw them. There, I'll nurse them for you while I eat this delicious-looking piece of pink rock."

The new girl was so utterly different from anybody else who had ever come to St. Chad's that the others waited with curiosity to hear what she would say next.

"Well?" she enquired coolly at last. "I suppose you're thinking me over. I should like to know your opinion of me. They tell me at home that my nose turns up, and my tongue is too long. But I didn't turn up my nose at the Edinburgh rock, did I?—and as for my tongue, it fits my mouth, as a general rule, though it runs away sometimes."

"When did you come?"

"What class are you in?"

"Have you seen Miss Cavendish yet?"

"How old are you?"

"Have you been to school before?"

"Do you know anyone here?"

"Why did you come to St. Chad's?"

The questions were fired off all together from seven pairs of lips.

"One at a time, please!" returned Honor. "I'm older than I look, and younger than I seem. You mayn't believe me, yet I assure you I've only had three birthdays."

"Rubbish!" said Chatty Burns.

"It's a fact, all the same."

"But how could that be?" demanded Pauline Reynolds incredulously.

"Because I was born on the twenty-ninth of February, and I can't have a birthday except in a leap year. That accounts for anything odd there is about me; so if you find me queer, you must just say: 'She's a twenty-ninth of February girl', and make excuses for me. As for the other questions, I've never been to school before; I've seen Miss Cavendish, but I haven't heard yet what class I'm to be in; five minutes ago I didn't know anybody here, but now I know—how many are there of you?—one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine!"

"Have you unpacked yet?" asked Maisie, returning to her box, which Lettice had been steadily emptying.

"Only about half."

"I think we had better come and help you, then."

"Better finish our own first!" grunted Lettice, for which remark she was promptly snubbed by her elder sister.

"Miss Maitland will be up at eight o'clock to look at our drawers," said Chatty Burns. "She'll expect you to have everything put away, and your coats and dresses hung in the wardrobe."

"We have to be so fearfully tidy here!" sighed Adeline Vaughan. "A warden comes round each morning, and woe betide you if you leave hairs in your brush, or have forgotten to fold your nightdress!"

"It's just as bad at St. Hilary's," said Madge.

"And worse at St. Bride's," added Ruth Latimer.

"My father wanted me to be at the School House," said Honor, "but Miss Cavendish wrote that it was full, so I was entered at St. Chad's instead."

"Yes, you generally need to have your name down for two years before you can get a vacancy at the School House," said Dorothy Arkwright. "It's the popular favourite with parents, because Miss Cavendish herself is the Head; but really, St. Chad's is far nicer. We all stand up for our own house, and I know you'll like it."

"There's the tea-bell! Come along! we must go at once," interrupted Chatty Burns.

"Won't they wait for us?" enquired Honor, beginning to wash her hands with much deliberation.

"Wait! She asks if they'll wait!" exclaimed Adeline Vaughan.

"One can see you've never been to school before!" commented Maisie Talbot. "No, you certainly haven't time to comb your hair now. You had better follow the rest of us as fast as you can."

St. Chad's could accommodate forty pupils, and Honor found a place assigned to her in the dining-hall near the end of a long table, which looked very attractive with its clean white cloth, its pretty china, and its vases of flowers in the middle. She had a good view of her schoolfellows, more than half of whom seemed of about the same age as herself, though there were tall girls, with their hair already put up, and a few younger ones who had apparently only just entered their teens. Grace was sung, and then the urns began to fill an almost ceaseless stream of cups, while plates of bread and butter circulated with much rapidity.

"We're late to-day," explained Honor's neighbour, "because the train from the North does not get in until five. Our usual tea-time is four o'clock, after games; then we have supper at half-past seven, when we've finished evening preparation. Did you bring any jam? Your hamper will be unpacked to-morrow, and the pots labelled with your name. I expect you'll find one opposite your plate at breakfast. Jam and marmalade are the only things we're allowed, except plain cakes."

Tea on the first afternoon was generally an exciting occasion at St. Chad's. There were so many greetings between old friends, so much news and such various topics to be discussed, that conversation, in a sufficiently subdued undertone, went on very briskly. The girls had enjoyed their Easter holidays, but most of them seemed pleased to return to school, for the summer term was always the favourite at Chessington College.

"Have you heard who's in the Eleven?" began Madge Summers. "They've actually put in Grace Shaw, and she bowls abominably. I think it's rank favouritism on Miss Young's part. She always gives St. Hilary's a turn when she can."

"She was a Hilaryite herself," returned Adeline Vaughan. "That's the worst of having a games mistress who's been educated at the school; she's sure to show partiality for her old house."

"And yet in one way it's better, because she understands all our customs and private rules. It would be almost impossible to explain everything to a new-comer."

"What about the house team?" asked Ruth Latimer. "Is anything fixed?"

"Not yet. There's to be a practice to-morrow, and it will go by our scores."

"I shall stick to tennis," declared Pauline Reynolds. "One gets a fair chance there, at any rate, and we must keep up the credit of St. Chad's in the courts. I don't know whether we've any chance of winning the shield. I wish we could get a real champion!"

"You should see Flossie Taylor play!" burst out Edith and Claudia Hammond-Smith, who were anxious to bring their cousin forward, and to ensure her popularity among the other girls.

"I've not heard that she made any record at St. Bride's," remarked Dorothy Arkwright, who resented Flossie's removal to St. Chad's.

"She hasn't had an opportunity. She only came to school last Christmas, and it wasn't the tennis season. Wait till you see her serve!"

"Miss Young will have to be judge, not I," replied Dorothy coldly.

"Flossie is in your bedroom, Dorothy," announced Claudia. "She has the cubicle near the fireplace."

"If you're sleeping in the bed next to mine," said Flossie, eyeing Dorothy across the table with a rather patronizing air, "I sincerely hope you don't snore."

"Of course not!" responded Dorothy, in some indignation.

"At St. Bride's," continued Flossie, "one of my room-mates snored atrociously. I used to have to get up and shake her, and pull the pillow from under her head, before I could go to sleep."

"You'd better not try that on with me!"

"I would, in a minute, if you kept me awake."

"It is a shame she's not in our room," interposed Edith. "We've asked Miss Maitland to let her change with Geraldine Saunders, and I think perhaps she may. We want Flossie all to ourselves; I do hope she'll let us!"

"So do I!" retorted Dorothy feelingly. "The Hammond-Smiths are welcome to their cousin, so far as I'm concerned," she whispered to Chatty Burns; "I don't like her. She's trying to show off. Edith and Claudia are making far too much fuss over her."

"They always gush," commented Chatty. "Still, I dare say Flossie will need taking down a little."

"It would do her all the good in the world," replied Dorothy. Then, turning to the Hammond-Smiths, she remarked aloud: "There's a new girl here who may be just as good as your cousin, for anything we know. Honor Fitzgerald, do you play tennis?"

"I can play, but how you'll like it is another story," answered Honor. "We two," nodding at Flossie, "had better try a set by ourselves, and then you can choose the winner."

"I'm sure I don't care about it, thank you." Flossie's tone was supercilious.

"All right! We don't force ourselves where we're not wanted in my part of the world."

"Is that Ireland? Then I suppose your name is Biddy?"

"Certainly not!"

"I thought all Irish girls were called Biddy; are you sure you're not?"

"My name is Honor Fitzgerald."

"Really! I'm astonished it isn't Mulligan, or O'Grady."

The Hammond-Smiths giggled, and poked Effie and Blanche Lawson.

"Isn't Flossie funny?" they whispered delightedly.

"I think she's very rude," observed Dorothy Arkwright. "I call that an extremely cheap form of wit."

"Irish names are often rather peculiar," drawled Claudia Hammond-Smith.

"They're quite as good as English ones, and sometimes a great deal more ancient and aristocratic," returned Honor.

"One for Claudia, and for Flossie Taylor too!" said Dorothy to Chatty Burns.

"Paddy, for instance," interposed Flossie, who saw that the Lawsons were listening, as well as her cousins. "St. Patrick and pigs always go together, in my mind. I suppose you keep a pig in Ireland?"

"Don't answer her!" whispered Honor's neighbour. "They're only teasing you because you're new. They want to see how much you'll stand."

But poor Honor was unaccustomed as yet to schoolgirl banter, and could not abstain from replying:

"Does it matter whether we do or not?"

She spoke quietly, but there was a gleam in her eye, as if her temper were rising.

"Not in the least! I only thought all Irish people cultivated pigs."

"It's no worse than keeping a cat, or a dog."

"My dear Paddy, of course not! Still, I shouldn't care to have the creatures in the drawing-room. Take a little more bread and butter. I'm sorry we've no potatoes to offer you."

The Hammond-Smiths and the Lawsons tittered, and Dorothy Arkwright was about to state her frank opinion of their behaviour when Honor's pent-up wrath exploded.

"We don't keep pigs in the drawing-room," she exclaimed. "There's a saying that it takes nine tailors to make a man, so if your name is Taylor you can only be the ninth part of a lady!" Then, realizing that her upraised voice had drawn upon her the attention, not only of all the girls, but also of Miss Maitland, she flushed crimson, scraped back her chair, and fled precipitately from the room.

Miss Maitland looked surprised. It was an unheard-of thing for any girl to leave the tea-table without permission. Such a breach of school decorum had surely never been committed before at St. Chad's! There was a very complete code of etiquette observed at the house, and to break one of the laws of politeness was considered an unpardonable offence.

"She's made a bad beginning," whispered Ruth Latimer to Maisie Talbot. "It's most unfortunate. It was really the fault of Flossie Taylor and the Hammond-Smiths. They needn't have teased her so."

"Still, it was silly of her to lose her temper," replied Maisie. "She stalked out of the room like a queen of tragedy. Miss Maitland can't bear girls who give way to their impulses; she despises what she calls 'early Victorian hysterics', and I quite agree with her."

"Yes, we must learn to be stoics here," said Ruth; "and as for teasing, the wisest thing is to take no notice of it."

A monitress had been dispatched to fetch Honor back, but in a short time she returned alone, and reported that she could not find her. Miss Maitland made no comment, and as the meal was now over she gave the signal of dismissal. Most of the girls went to the recreation room, but Maisie Talbot, who had not yet quite concluded her unpacking, ran straight upstairs. Noticing something move behind a curtain in the corner of the bedroom, she pulled it aside. There was Honor, sitting in a queer little heap on the floor, and rubbing her eyes in a very suggestive manner. She jumped up in a moment, however, and pretended that she was only arranging her boots.

"I'd finished tea," she remarked airily, "so I thought I might as well empty my box, and put my dresses away in my wardrobe."

"You'll have to ask Miss Maitland's leave next time, before you march out of the room, or you'll get into trouble," said Maisie. "If it weren't your first evening, you'd be expected to make a public apology. Of course, Flossie Taylor and the Hammond-Smiths were aggravating, but you should just have laughed at them, and then they'd have stopped. We don't behave like kindergarten children here."

Maisie spoke scathingly. She was a girl who had scant sympathy with what she called "babyishness", and disliked any exhibition of feeling. And, after all, she only voiced the general opinion of the school, which, by an unwritten law, had established a calm imperturbation as the height of good breeding.

"I don't care in the least what any of you think!" retorted Honor, and she hung up her skirt with such a jerk that she broke the loop.

Yet, although she spoke lightly, she evidently did care. She was very quiet indeed all the rest of the evening, and hardly spoke at recreation. Chatty Burns sat down next to her and tried to begin a conversation, but Honor answered so briefly that she very soon gave up the effort in despair, and moved away; while the other girls were so interested in their own affairs that they did not trouble to remember their new schoolfellow. At nine o'clock prayers were read, and everybody went upstairs to bed.

When the lights were out, and the room was in perfect silence, a strange, suppressed noise issued from Honor's corner. It might, of course, have been snoring; and Honor explained elaborately next morning that Irish people often have a peculiar way of breathing in their sleep—an affection from which she sometimes suffered herself.

"All the same, I don't quite believe her," confided Pauline Reynolds, who occupied the next cubicle, to Lettice Talbot, a more sympathetic character than her sister Maisie. "I know what it is to feel home-sick, and to smother one's nose in the pillow! If that wasn't sobbing, it was as like it as anything I've ever heard in my life."

CHAPTER II

Honor's Home

For a full understanding of Honor Fitzgerald we must go back a few weeks, and see her in that Irish home which was so far away and so utterly different from Chessington College. Kilmore Castle was a great, rambling, old-fashioned country house, built beside an inland creek of the sea, and sheltered by a range of hills from the wild winds of Kerry. To Honor that was the dearest and most beautiful spot in the world. She loved every inch of it—the silvery strips of water that led between bold, rocky headlands out to the broad Atlantic; the tall mountain peaks that showed so rugged an outline against the sky; the brown, peat-stained river that came brawling down from the uplands, and poured itself noisily into the creek; the wide, lonely moors, with their stretches of brilliant green grass and dark, treacherous bog pools; and the craggy cliffs that made a barrier against the ever-dashing waves, and round which thousands of sea birds flew, with harsh cries and whir of white wings.

Its situation at the end of a long peninsula made Kilmore Castle an isolated little kingdom of its own. On the shore stood a row of low, fishermen's white-washed cabins, dignified by the name of "the village"; but otherwise there was no human habitation in sight, and Ballycroghan, the market town and nearest postal, railway, and telegraph station, was ten miles off.

Trees were rarities at Kilmore; a few stunted specimens, all blown one way by the prevailing gale, grew as if huddled together for protection at the foot of the glen, but they were the exception that proved the rule; nevertheless, under the sheltering walls of the Castle Mrs. Fitzgerald had managed to acclimatize some exotic shrubs, and to cultivate quite a beautiful garden of flowers, for the temperature was uniformly mild, though the winds were boisterous. Brilliant St. Brigid's anemones, the poet's narcissus, tulips, jonquils, and hyacinths bloomed here almost as early as in the Scilly Isles, and made patches of fragrant brightness under the sitting-room windows; while in the crannies of the walls might be seen delicate maidenhair and other ferns, too tender generally to stand a winter in the open.

Born and bred in this far-away corner of the world, Honor had grown up almost a child of nature. Her whole life had been spent as much as possible out-of-doors, boating, fishing, or swimming in the creek; driving in a low-backed car over the rough Kerry roads; galloping her shaggy little pony on the moors; following the otter hounds up the river, and sharing in any sport that her father considered suitable for her age and sex. She was the only girl among five brothers, and in her mother's opinion was by far the most difficult to manage of the whole flock. All the wild Irish blood of the family seemed to have settled in her; the high spirits, the fire, the pride, the quick temper, the impatience of control, the happy-go-lucky, idle, irresponsible ways of a long line of hot-headed ancestors had skipped a generation or two, and, as if they had been bottling themselves up during the interval, had reappeared with renewed force in this particular specimen of the Fitzgerald race.

"She's more trouble than the five boys put together," her mother often declared, and her friends cordially agreed with her. Mrs. Fitzgerald herself was a mild, quiet, nervous, delicate lady, as much astonished at her lively, tempestuous daughter as a meek little hedge-sparrow would be, that had hatched a young cuckoo. Frankly, she did not understand Honor, whose strong, uncontrolled character differed so entirely from her own gentle, clinging, dependent disposition; and whose storms of grief or anger, wild fits of waywardness and equally passionate repentance, and self-willed disobedience, alternating with sudden bursts of reformation, were a constant source of worry and anxiety, and the direct opposite of her ideal of girlhood. Poor Mrs. Fitzgerald would have liked a docile, tractable daughter, who would have been content to sit beside her sofa doing fancy work, instead of riding to hounds; and who would have had more consideration for her weak state of health. She appreciated Honor's warm-hearted affection to the full, but at the same time wished she could make her realize that rough hugs, boisterous kisses, and loud tones were hardly suitable to an invalid. Suffering as she was from a painful and incurable complaint, it was sometimes impossible for her to admit Honor to her sick-room, and for weeks together the girl would hardly see her mother. It was through no lack of love that Honor had failed to give that service and tenderness which, in the circumstances, an only daughter might so fitly have rendered; it was from sheer want of thought, and general heedlessness. Some girls early acquire a sense of responsibility and care for others, but in Honor these qualities were as undeveloped as in a child of six.

Many were the governesses who had attempted to tame the young rebel, and bring her into a state of law and order, but all had been equal failures. She had learnt lessons when she felt inclined, and left them undone when she was idle; and she had managed to make life in the schoolroom such a purgatory that it had been difficult to persuade any teacher to stay long at the Castle, and cope with so thankless a task as her education.

It had been of little use to complain to her father, the only person in the world whose authority she recognized; he was proud of his handsome daughter, and, except when her temper crossed his own, was apt to indulge her in most of her whims. Matters had at last, however, come to a crisis. An act of more than usual assumption on Honor's part had aroused Major Fitzgerald's utmost indignation, and had caused him suddenly to decide that she was spoiling at home, and that the only possible solution of the difficulty was to dispatch her to school as soon as the necessary arrangements could be made for her departure.

The incident that led to this resolution was very characteristic of Honor's headstrong, impulsive nature. She was passionately fond of horses, and for some time had been anxious to possess a new pony. It was not that she loved Pixie, her former favourite, any the less; but he was growing old, and was now scarcely able to take a fence, or carry her in mad career over the moors, being only fit for a sober trot on the high road, or to draw her mother's Bath chair round the garden. To obtain a strong, well-bred, fiery substitute for Pixie was the summit of Honor's ambition. One day, when she was with her father at Ballycroghan, she saw exactly the realization of her ideal. It was a small black cob, which showed a trace of Arab blood in its arching neck, slender limbs, and easy, springy motion. Though its bright eyes proved its high spirit, it was nevertheless as gentle as a lamb, and well accustomed to carrying a lady. Its owner, a local horse-dealer, was anxious to sell it, and pressed Major Fitzgerald to take it as a bargain. Honor simply fell in love with it on the spot. She ascertained that its name was Firefly, and begged and besought her father to buy it for her. But on this occasion he would not yield, even to her utmost coaxing. He did not wish to keep another pony in the stable, and he considered the price asked was excessive, and entirely beyond the present limits of his purse.

"No, Honor, it can't be done," he said. "You must be content with poor old Pixie. I have quite enough expenses just now, without running into such an extravagance."

"But couldn't I have it instead of something else?" pleaded Honor.

"There's nothing we could knock off, dear child," replied her father.

"I could do without a governess," suggested Honor hopefully. "I'd set myself my own lessons, and learn them too. Oh, Daddy, darling, if we gave up Miss Bury, wouldn't you have money enough to buy Firefly?"

Major Fitzgerald laughed in spite of himself.

"I consider Miss Bury a necessity, and not a luxury," he replied. "A governess is the very last person we could dispense with. I should like to see you setting your own lessons! Remarkably short and easy ones they would be! No, little woman, I'm afraid Firefly is an impossibility, and you must just try to forget his existence."

Unfortunately, that was exactly what Honor could not do. She thought continually about the beautiful black cob, and the more she dwelt on her disappointment the more keenly she felt it. She considered, most unreasonably, that her governess was the alternative of the pony, and that if she were without the one she might possibly acquire the other. Her behaviour had never been exemplary, but on the strength of this grievance she grew so unruly, so disrespectful, and so absolutely unmanageable that Miss Bury at length refused to teach her any longer, and, after an interview with Major Fitzgerald in the library, packed her boxes and returned home to England.

Honor viewed her exodus with keen delight. It seemed the removal of an obstacle to her plan. She went in to luncheon determined to broach once more the subject of Firefly, hoping this time to meet with better success. She saw at once, however, from her father's face, that he was not in a suitable mood to grant her any favour. He was much annoyed at the governess's departure, for which he had the justice to blame Honor alone; and he was worried with business matters.

"That tiresome agent has not sent the telegram I expected," he announced. "I shall be obliged to go over to Cork, to consult my solicitor. Tell Murphy to have the trap ready by two o'clock, and let Holmes pack my bag. I shall probably be away until Friday evening."

As soon as her father had started for the station, Honor sauntered out in the direction of the stables. It was one of her mother's bad days. Mrs. Fitzgerald was confined to her room, therefore Honor, released from Miss Bury's authority, felt herself her own mistress. Finding Fergus, the groom, she ordered him to saddle Pixie, and make ready to accompany her on a ride. Fergus was devoted to "Miss Honor", and would never have dreamt of disputing any command she might give him; before three o'clock, therefore, her pony was at the door, and, dressed in her neat blue habit, she was ambling away in the direction of Ballycroghan. It was a leisurely progress, for poor Pixie's gait was slow, in spite of his best endeavours, and Honor loved him too well to urge him hard.

She was determined to call at the horse-dealer's, and to ascertain if Firefly were still for sale. Perhaps, when her father returned home, she might catch him at a favourable moment, and be able to cajole him into changing his mind and buying the cob. Mr. O'Connor, the horse-dealer, lived at a large farm on the way to the town, and, to Honor's intense delight, the first object that met her eyes on approaching the house was Firefly, feeding demurely in a paddock to the left of the road. By an equally lucky chance Mr. O'Connor happened to be at home, and came hurrying out at once when he saw "one of the quality", as he expressed it, drawing bridle at his door.

"Good afternoon! I see you still have the black cob," began Honor eagerly.

"Yes, missy," replied the horse-dealer, "and I was thinking of sending a message to your father about him this very day. It's the good fortune to see you here! I've had a man over from Limerick who's anxious to take him—a tradesman who'd run him in a light cart—but I didn't close the bargain at once. I said to my wife: 'Firefly is too good a breed to carry out groceries. I'd rather be for selling him to the Castle. Miss Fitzgerald took the fancy for him, and I'll not be parting with him till I've had word again from the Major.' Maybe his honour will be wanting him, after all? But sure I must know at once, for the Limerick man will be here at noon to-morrow, and I've promised to tell him one way or another."

"Could you possibly wait until Saturday?" asked Honor.

The dealer shook his head.

"I can't afford to miss a sale," he replied. "I've had the cob on my hands for some time; it's just eating its head off, and it's anxious I am to get rid of it."

Honor was in a fever of excitement. Firefly, so spirited and so aristocratic, whose delicately shaped limbs looked only fit for leaping brooks, or cantering over the short grass on the uplands, to be sold to a tradesman, and to run between the shafts of a cart that delivered groceries! It seemed a degradation and an outrage. She could not dream of allowing it; she must save him at any cost from such a fate.

"Must you absolutely have an answer to-day?" she asked.

"Yes, missy. I fear I couldn't put off Sullivan any longer than noon to-morrow. He's a touchy man, and ready to carry his business elsewhere."

"Very well, then, that settles the matter. We will take the cob. You may send him over to the Castle this evening."

Honor spoke in such a high-handed manner that the dealer never guessed she was acting on her own authority. As she had made a special visit to the farm, accompanied by her groom, he imagined she must have been entrusted by Major Fitzgerald with full powers to buy the pony if she wished.

"Many thanks to you, missy! It's the fine mistress you'll make for Firefly. My respects to his honour, and the price shall be the same as I was asking him before."

The price! Honor had quite forgotten that. Weighed against Firefly's possible future, it had seemed an unimportant detail. She remembered now, however, that her father had considered it extravagant, and declared he could not afford it. The thought was sufficient to check her joy suddenly, and to send her home in a sober frame of mind that was well justified by the sequel.

Major Fitzgerald's wrath, when he arrived on the Friday and found the black cob installed in the stable, was more serious than his daughter had ever experienced before.

"It was a piece of unwarranted presumption!" he declared. "I shall not allow you to keep the pony. It must be sent back to O'Connor's, and resold at the first opportunity. As for you, the sooner you are packed off to school the better. We have indulged you too much at home, and it is time indeed that you learnt to submit to some kind of discipline."

The proposal to send her away to school was a terrible blow to Honor. At first she appealed to her mother, begging her to plead with her father and try to persuade him to alter his resolution. But Mrs. Fitzgerald, while regretting to part with her troublesome daughter, was so convinced of the wisdom of the proceeding that, instead of interceding, she applauded her husband's decision.

"I can't ever like England!" sobbed Honor. "I'd rather have our mountains and lakes and bogs than all the grand streets and houses. I'm Irish to the core, and I don't believe any school over the water can change me. There's no place in the world like Kilmore. I love even the cabins, and the peat fires, and the pigs, and the potatoes! I shan't forget a single stick or stone of it, and I shall never know a moment's happiness till I'm home again."

After considerable hesitation, and the examination of a large number of prospectuses, Major and Mrs. Fitzgerald had determined to send Honor to Chessington College. It had a wide and well-deserved reputation, and Miss Cavendish, the principal, was understood to give much individual attention to the characters and dispositions of her pupils. Added to this, it was situated within a few miles of the Naval Preparatory School where Dermot, Honor's younger brother, had been for the last two years; so that they knew from experience that the neighbourhood was bracing and healthy.

"It's a comfort, at any rate, that I shall be near Dermot," said Honor, as she sat watching while her mother superintended the maid who was packing her boxes.

"I'm afraid you won't see much of him, dear, during term-time," replied Mrs. Fitzgerald. "He will not be able to visit you, I'm sure; neither will Miss Cavendish allow you to go out with him."

"Why not?" demanded Honor.

"Because it would be against the rules."

"Then the rules are absurd, and I shan't keep them."

"Honor! Honor! Don't speak like that! You have run wild here, but at Chessington College you will be obliged to fall in with the ordinary regulations."

"They'll have hard work to tame me, Mother!" laughed Honor, jumping up and dancing a little impromptu jig between the boxes. "I don't want to go, but since I must, I mean to get any enjoyment I can out of it. After all, perhaps it may be rather fun. It's deadly dull here sometimes, when the boys are at school, and Father is busy or away."

Mrs. Fitzgerald sighed. In her delicate health she could scarcely expect to be a companion for Honor, yet when she thought of how few years might be left them together, the parting seemed bitter, and she was hurt that her only daughter would evidently miss her so little. Young folks often say cruel things from mere thoughtlessness, and unintentionally grieve those who love them. In after years Honor would keenly regret her tactless speech, and blame herself that she had not spent more hours in trying to be a comfort, instead of a care; but for the present, though she noticed the look of disappointment that passed over the sensitive face, she did not fully realize its cause, and the words that might have healed the wound went unspoken.

At length the preparations were concluded, and the time had almost arrived to bid farewell to Kilmore Castle and the surrounding demesne. Honor's friends in the village mourned her approaching departure with characteristic Irish grief.

"Miss Honor, darlint, it's meself that will be hungerin' for a sight of yez!" cried old Mary O'Grady, standing at the doorway of her thatched cabin, from which the blue peat smoke issued like a thin mist.

"And it's grand news entoirely they'll be afther tellin' me too, that ye're lavin' the Castle, and goin' over the seas!" put in Biddy Macarthy, a next-door neighbour of Mary's. "It's fine to think of all the iligant things ye'll be seein' now!"

"Bless your bright eyes, it's many a sad heart ye'll lave behind yez!" added Pat Conolly, the oldest tenant on the estate.

"England can never compare with dear Ireland, in my opinion," replied Honor, with a choke in her voice. "There's no spot so sweet as Kilmore, and all the while I'm away I shall be wishing myself back in the 'ould counthree'!"

"Will ye be despisin' this bit of a present, Miss Honor?" said old Mary, producing a cardboard box, from which, out of many folds of tissue paper, she proudly displayed a large bunch of imitation four-leaved shamrock. "My grandson Micky brought it for me all the way from Dublin city, and I've kept it fine and new in its papers. Sure, I know it's not worthy of offerin' to a young lady like yourself, but I'll take it kindly if ye'll deign to accept it."

"Of course I'll accept it!" returned Honor heartily. "It's very kind of you to give it to me. It shall go to school with me, as a remembrance of Ireland, and of you all."

"The four-leaved shamrock brings good luck to its wearer, mavourneen; may it bring it to you! And whenever ye look at the little green leaves, give a thought to the true hearts that will be ay wishin' ye a speedy return."

The last day came all too soon, and Mrs. Fitzgerald, with tears in her eyes, stood at her window, watching the disappearing carriage in which Honor sat by her father's side, waving an energetic good-bye.

"Surely," she said to herself, "school will have the influence that we expect! The general atmosphere of law and order, the well-arranged rules, the esprit de corps and strict discipline of the games, all cannot fail to have their effect; and among so large a number of companions, and in the midst of so many new and absorbing interests, my wild bird will find her wings clipped, and will settle down sensibly and peaceably among the others."

CHAPTER III

The Wearing of the Green

Chessington College stood on a breezy slope midway between the hills and the sea, and about a mile from the rising watering-place of Dunscar. It was a famous spot for a school, as the fresh winds coming either from the uplands or from the wide expanse of channel were sufficient to blow away all chance of germs, and to ensure a thoroughly wholesome and bracing atmosphere. The College prided itself upon its record of health; Miss Cavendish considered no other girls were so straight and well-grown as hers, with such bright eyes, such clear skins, and such blooming cheeks. Ventilation, sea baths, and suitable diet were her three watchwords, and thanks to them the sanatorium at the farther side of the shrubbery scarcely ever opened its doors to receive a patient, while the hospital nurse who was retained in case of emergencies found her position a sinecure.

The buildings were modern and up-to-date, with all the latest appliances and improvements. They were provided with steam heat and electric light; and the gymnasium, chemical laboratory, and practical demonstration kitchen were on the very newest of educational lines. The school covered a large space, and was built in the form of a square. In the middle was a great, gravelled quadrangle, where hockey could be practised on days when the fields were too wet for playing. At one end stood the big lecture-hall, the chapel, the library, and the various classrooms, the whole surmounted by a handsome clock tower; while opposite was the School House, where Miss Cavendish herself presided over a chosen fifty of her two hundred pupils. The two sides of the square were occupied by four houses, named respectively St. Aldwyth's, St. Hilary's, St. Chad's, and St. Bride's, each being in charge of a mistress, and capable of accommodating from thirty to forty girls. Though the whole school met together every day for lessons, the members of each different house resembled a separate family, and were keenly anxious to maintain the honour of their particular establishment. Miss Cavendish did not wish to excite rivalry, yet she thought a spirit of friendly emulation was on the whole salutary, and encouraged matches between the various house teams, or competitions among the choral and debating societies. The rules for all were exactly similar. Every morning, at a quarter to seven, a clanging bell rang in the passages for a sufficient length of time to disturb even the soundest of slumbers; breakfast was at half-past seven, and at half-past eight everybody was due in chapel for a short service; lectures and classes occupied the morning from nine till one, and the afternoon was devoted to games; tea was at four, and supper at half-past seven, with preparation in between; and after that hour came sewing and recreation, until bedtime. It was a well-arranged and reasonable division of time, calculated to include right proportions of work and play. Mens sana in corpore sano was Miss Cavendish's favourite motto, and the clean bill of health, the successes in examinations, and the high moral tone that prevailed throughout pointed to the fulfilment of her ideal. Most of the girls were thoroughly happy at Chessington College, and, though it is in girl nature to grumble at rules and lessons, there was scarcely one who would have cared to leave it if she had been given the opportunity.

It was to this new, interesting, and exciting world of school that Honor unclosed her eyes on the morning after her arrival. She opened them sleepily, and, I regret to say, promptly shut them again, and turned over comfortably in bed, regardless of the vigorous bell that was delivering its warning in the passage. Punctuality had not been counted a cardinal virtue at Kilmore Castle, and she saw no special necessity for rising until she felt inclined. She had just dropped off again into a delicious doze when once more her peace was rudely disturbed. The curtain of her cubicle was drawn back, and three lively faces made their appearance.

"Look here! Don't you know it's time to get up?" said Maisie Talbot, administering a vigorous poke that would have roused the Seven Sleepers of legendary lore, and caused even Honor to yawn.

"You'll be fined a penny if you're late for breakfast," added Lettice, "and that's a very unsatisfactory way of disposing of one's pocket-money."

"And makes Miss Maitland particularly irate," said Pauline Reynolds.

"Honor Fitzgerald! do you intend to get up, or do you not? Because if you don't, we shall have to try 'cold pig'!" Then, as there were no signs of movement, Lettice carried out her threat by dabbing a wet sponge full in Honor's face, while at the same moment Maisie wrenched back the bed-clothes with a relentless hand.

"We're doing you a real kindness, so you needn't be cross, Miss Paddy Pepper-box!" said Lettice. "Just wait till you've seen Miss Maitland scowl at a late-comer, and you'll give us a vote of thanks."

"I'm not cross," said Honor, laughing in spite of the violation of her slumbers. Lettice spoke so merrily, it was impossible to take offence, even at the nickname. "But I think you use rather summary measures. The sponge was horribly cold and nasty."

"It's the only way to get people to bestir themselves," said Lettice complacently. "I've had experience with sleepy room-mates before."

"We always try the water cure at St. Chad's," added Maisie. "We've given you quite mild treatment, as it was a first case; we might have used your bedroom jug, instead of a sponge."

Owing to her companions' efforts, Honor was in time for breakfast—a fortunate circumstance for her, as, after the episode at the tea-table on the preceding evening, her house-mistress would not have been ready to overlook any deficiency in punctuality.

There was always a short recess between breakfast and chapel, which the girls called a "breathing space", and during which they could revise exercises, sharpen lead pencils, and take a last peep at lessons. This morning everybody seemed to be assembling in the dressing-room for this brief interval, and there Honor repaired with the others.

"I hear you've been put in the Lower Third, Paddy," said Lettice Talbot. "Vivian Holmes told me so just now. It's my form. Maisie and Pauline are in it too."

"Isn't Maisie above you?" asked Honor, looking at the sisters, the elder of whom overtopped the younger by nearly a head. "She is in inches, at any rate."

"I'm only a year older than Lettice, though I am so much taller," explained Maisie. "I suppose I ought to be in a higher form, but she always manages to catch me up. I make up my mind every term I'm going to win a double remove and leave her behind, yet somehow it never happens to come off. I'm much better at cricket and hockey than at French and algebra. But after all, it's rather convenient to have her in the same form: she's sure to remember what the lesson is when I forget, and I can borrow her books if I lose my own."

"Yes, I have to work for both," complained Lettice. "Maisie won't even copy her exercise questions; she always relies on me."

Maisie certainly made her younger sister useful. She expected her to fetch and carry, tidy both their cubicles, and generally maintain a very subservient and inferior position. On the other hand, though she tyrannized over Lettice herself, she would not allow anybody else to do so, and was ready to take her part and fight her battles against the whole school.

"I'm glad we're in the same class," remarked Honor, with an approving glance at Lettice's round, smiling face. "Perhaps I shall ask you to copy the exercise questions too. My memory is not particularly good where lessons are concerned. Who else is in the Lower Third?"

"Ruth Latimer, my greatest chum."

"We allow ourselves chums," put in Maisie, "but we're not at all romantic at Chessington. We don't swear eternal friendships, and exchange locks of hair, and walk about the College with our arms clasped round each other's necks, and write each other sentimental notes, with 'sweetest' and 'darling' and 'fondest love' in them. That's what Miss Maitland calls 'early Victorian'. We're very matter of fact here. Still, when we choose a chum we generally stick to her, and don't go in for all that nonsense of 'getting out of friends', or not speaking, as they do at some schools."

Honor was about to ask more questions, but at that moment Vivian Holmes, the monitress and head girl of the house, came bustling into the room.

"You haven't got your sailor and jersey yet, Honor Fitzgerald," she said. "Miss Maitland asked me to give them to you. Here they are, both marked with your name, so that they needn't be mixed up with anybody else's. You're to take this hook, and this compartment for your shoes, and this locker to keep your books in. I've put labels on them all."

Honor looked without enthusiasm at the knitted woollen coat, and with marked disfavour at the white sailor hat, with its band of orange ribbon.

"I can't wear that!" she ejaculated.

"Why not?" enquired Vivian, in surprise.

"There's an orange band round it."

"Orange is the St. Chad's colour," explained Vivian. "We all have exactly the same hats at Chessington, but each house has its own special ribbon—blue for the School House, pink for St. Aldwyth's, scarlet for St. Hilary's, and violet for St. Bride's. I thought you knew that already."

"If I had, I'd have insisted upon going to another house," declared Honor tragically. "You ask me to wear orange? Why, the very name of 'Orangeman' sets my teeth on edge. I'm a Nationalist to the last drop of my blood; we all are, down in Kerry."

Vivian smiled.

"Don't be absurd!" she said, in rather an off-hand manner. "Our hats have nothing whatever to do with politics. Here are two long pins, but if you prefer an elastic you can stitch one on," and without deigning to argue further she walked away.

Honor stood turning the hat round and round, with a very queer expression on her face. She was a devoted daughter of Erin. Her country's former glories and the possible brilliance of its future as a separate kingdom could always provoke her wildest enthusiasm; to be asked, therefore, to don the colour which in her native land stood as the symbol of the union with England, and for direct opposition to national independence, seemed to her little short of an insult to her dear Emerald Isle. There were still five minutes left before she need start for chapel, so, making up her mind suddenly, she rushed upstairs to her bedroom. She would show these Saxons that she was a true Celt! They might compel her to wear their emblem of bondage, but it should be with an addition that would proclaim her patriotic sentiments to the world.

Hurriedly hunting in her top drawer, she produced a yard of vivid green ribbon and the bunch of imitation shamrock that old Mary O'Grady had given her as a parting present. Then she set to work on a piece of amateur millinery. There was little time to use needle and thread, but with the aid of pins she managed to twist the ribbon into several loops, and to fasten the shamrock conspicuously in front. She looked at the result of her labours with great approval.

"One could almost imagine it was St. Patrick's Day," she said to herself. "Nobody could possibly mistake me now for a Unionist. I'm labelled 'Home Rule' as plainly as can be." Then, hastily pinning on her hat before the mirror, she ran downstairs, humming under her breath:

"So we'll bide our time; our banner yet

And motto shall be seen,

And voices shout the chorus out,

'The Wearin' o' the Green'!"

The girls at Chessington College were all dressed exactly alike, in a uniform costume of blue serge skirts, with blue or white cotton blouses for summer, and flannel ones for winter. On Sundays they wore white serge coats and skirts, and for evenings white muslin or nuns' veiling. They were allowed a little latitude in the way of embroideries with respect to best frocks, but their everyday, ordinary clothes were required to be of the school pattern, with the addition of sailor hats and knitted coats, for use in running across the quadrangle on wet or cold days. Miss Cavendish considered that this rule encouraged simplicity, and provided against any undue extravagance in the matter of dress. She did not allow rings or bracelets to be worn, and the sole vanity permitted to the girls was in the choice of their hair ribbons.

Punctually at twenty-five minutes past eight each morning the bell in the little chapel began to give warning, and by half-past every member of the school was expected to have taken her seat, and to be ready for the short service held there daily by the senior curate of the parish church at Dunscar. In twos and threes and small groups the girls came hurrying in answer to the call of the tinkling bell. Though they laughed and talked as they ran across the quadrangle, they sobered down as they neared the door, and, each taking a Prayer Book from a pile laid ready in the porch, passed silently and reverently into the chapel. Every house had its own special rows of seats, and the sailor hats that mingled like a kaleidoscope in the grounds were here divided into their several sets of colours, though sometimes varied by a gleam of ruby or amber falling from the stained-glass windows above. The singing was musical and the responses hearty, while into his five minutes' explanation of the lesson for the day the clergyman generally managed to compress much helpful thought, sending away some, at least, of his hearers braced up for the duties that awaited them.

On this particular morning anyone accustomed to the ordinary atmosphere of the place might have been aware that something of an unusual character was in the air.

There was an undercurrent of unrest, a turning of heads, a subdued rustling, even an occasional whisper; and the head mistress, realizing at last that some outside cause must be distracting the minds of her pupils, glanced up, and, following the direction of all eyes, saw a sight that filled her with unfeigned astonishment. Among the neat rows of orange-banded sailor hats in the benches marked "St. Chad's" was one trimmed with large and obtrusive knots of emerald-green ribbon, which drooped over the brim, while a bunch of imitation shamrock finished the front. It seemed to stand out so conspicuously from its fellows that it resembled a succulent palm tree growing in the midst of a sandy desert, and could not fail to attract the attention of the whole school. How such an irregularity had crept in amongst the uniforms of the college Miss Cavendish could not comprehend; it must form the subject of an after enquiry, and in the meantime, stilling with a reproachful glance a faint whisper in her vicinity, she joined in the singing of a psalm with her usual clear intonation. When the service was over, however, and the girls began to file away in orderly line, she spoke a few, rapid words to a monitress, who at once passed quickly out by a side door.

As the extraordinary green hat made its appearance in the quadrangle it was greeted with quite a buzz of excitement by the girls assembled outside. Only a few of them, comparatively, knew Honor by sight, and the rest were asking who she was, and to which house she belonged. The common feeling was distinctly unfavourable. Apart from the unseemliness of such an exhibition in a sacred place, new girls were not expected to make themselves conspicuous, or to introduce innovations; either was considered an impertinence on their part: so the general verdict was that Honor had done a dreadful thing, and public opinion was dead against her. She, however, held up her head as proudly as though her absurd hat had been the latest creation from Bond Street.

"It's a tribute to my native land!" she said airily, in response to a chorus of questions. "Sorry you don't like it, but it's my first attempt at hat-trimming, and I flattered myself it wasn't bad for a beginner. St. Patrick for ever! I made up my mind before I started that I'd keep up the credit of the shamrock on this side of the water, and I've done my best. Hurrah for old Ireland!" Then, as if her feelings were absolutely too much for her, she took her skirt in her hands, and began to dance an old-fashioned Kerry hornpipe, humming a lively Irish tune to supply the music.

The girls stared in amazement at the mad performance. "She's showing off!" declared some, but others laughed, and watched with a kind of fascination, for the dance was striking and original, and the movements were unusually graceful.

Honor's triumph, however, was short-lived. Vivian Holmes forced her way through the crowd, and, laying her hand on the shoulder of the obstreperous new-comer, told her to report herself at once in Miss Cavendish's study. The lookers-on scuttled away to their classes without being told; they were half-ashamed of having taken so much notice of a new girl. Lettice Talbot, turning round, caught a glimpse of Honor walking blithely away, with a jaunty smile on her face.

"As if a visit to the head mistress meant nothing at all!" she gasped.

"She'll soon find out her mistake," replied Ruth Latimer grimly. "Miss Cavendish can reduce one to a quaking jelly when she feels inclined."

Honor was in one of her wildest, most reckless moods, and the prospect of a passage of arms with the principal of the College was as the call of battle to a knight of old. In her conflicts with her governesses at home she had invariably come off best, and it pleased her to think she had now the opportunity of trying her will in opposition to that of the ruler of this little kingdom.

Miss Cavendish's study was a beautiful and unusual room. It was built in accordance with an old-world design, and in shape resembled an ancient chapter-house. The richly carved chimney-piece, the dark panelling of the walls, and the straight-backed oak chairs helped to carry out the prevailing note of mediaevalism, which was further enhanced by a large, stained-glass window, filled with figures of saints, that faced the doorway. To enter was like going into the peace and serenity of some old cathedral, and, notwithstanding her defiant frame of mind, a feeling of something akin to reverence crept over Honor as she crossed the threshold. Her impressionable Celtic temperament could not fail to be influenced by outward surroundings: she had a great love of the beautiful, and this room satisfied her æsthetic tastes.

The head mistress was standing beside the hearth, which, though devoid of fire at this season of the year, was piled up with newly cut logs. In her long, clinging black dress, the light from the halo of St. Aldwyth in the window falling on her regular Greek features, and touching with a ruddier gleam the pale gold of her rippling hair, Miss Cavendish looked an imposing and commanding figure. Born of a good family, the daughter of a high dignitary of the Church, she was by nature a student, and after a brilliant career at Girton she had for a time devoted herself to scientific research, arousing much interest by her clever articles in various periodicals; but feeling that her true vocation was teaching, she had turned her attention to education, and, gaining a reputation in the scholastic world, had in course of time been elected as the principal of Chessington College, a post which she filled with dignity, and greatly to the satisfaction of both governors and parents. Not a remarkably tender woman, she was perhaps more respected than loved by her pupils; but she had great powers of administration, and managed to impress upon her girls a strict sense of duty and responsibility, a love of work, a fine perception of honour, and a desire to keep up the high tone and prestige of the school.

She turned her clear, cold blue eyes on Honor, as the latter entered the room, with a scrutinizing gaze, so comprehensive and so full of authority that, despite her intention of showing a bold front, the girl involuntarily quailed.

"Come here, Honor Fitzgerald," began Miss Cavendish, in a calm, measured tone. "I wish you to explain to me why you have taken it upon yourself to alter the costume which, you are well aware, is obligatory for all attending the College."

"I can't wear orange," replied Honor, plucking up her courage for the battle; "it's against my principles."

"There are right principles and wrong principles; we will decide presently to which class yours belong. On what grounds do you raise your objection?"

"I'm Irish," said Honor briefly, "so I prefer green."

"That is no reason. We have many nationalities here, and do you imagine that every girl can be permitted to carry out her individual taste? Tell me why you suppose such a rule was framed."

"I don't know," returned Honor rebelliously.

"Then you must think, for I require an answer."

Honor stared at the fireplace, at the bookcase, with its richly bound volumes; at the window, where the red robe of St. Hilary made such a glorious spot of colour; at the table, covered with books and papers; and finally her glance went back to the head mistress, whose eyes were still fixed on her with that steady, embarrassing gaze.

"Was it to make everybody look alike?" she replied at last, almost as if the words were dragged from her lips.

"Exactly! Then, to return to my original question, why, knowing this fact, did you presume to break the rule?"

Honor was again silent. Somehow her intended bravery seemed to desert her.

"I met your father, Major Fitzgerald, yesterday," continued Miss Cavendish. "I understand that he held a command in the Royal Munster Fusiliers, and did splendid service in the Boer War. Kindly tell me what explanation he would have given to his general if he had appeared at church parade minus his uniform."

"Oh, but he wouldn't have done that!" exclaimed Honor in horror.

"Why not?"

"Why! because he is a soldier. How could he? The uniform is part of the service."

"And what is the first duty of a soldier?"

"To obey orders," answered Honor, with a spark of apprehension in her eyes.

"You are right. Now, what would happen to a regiment if each individual, instead of obeying his superior officer, were to follow his own inclinations?"

"It would go to pieces."

"And what occurs when a soldier commits any breach of regulations?"

"He is court-martialled and punished."

"Is that just?"

"Yes."

"But why?"

"Oh, because—because—it's the Army, and they must! There couldn't be any discipline without."

"Exactly! You are an officer's daughter, and you evidently appreciate the vast importance of good discipline. Now, we are a little army here. Every girl, as a member of this community, is bound to preserve its rules, which have been wisely framed, and deserve to be faithfully kept. You have been guilty of a very grave breach of our regulations, and by your own showing you merit punishment. Do you consider this to be just?"

"Yes," returned Honor, meeting the head mistress's look firmly.

"We have an esprit de corps at the College," continued Miss Cavendish, "which makes each girl anxious to keep up the credit and prestige of the school. When you have been here a short time, and have learnt the tone of the place, I believe and trust that you will be truly ashamed of the remembrance of your appearance in chapel this morning. It is for this reason I shall not punish you, though you have yourself acknowledged that punishment would be only an act of justice. As for the matter of principle to which you referred, so far from advancing the good fame of your country, you were bringing it into disrepute. If you imagine it was a particularly patriotic deed to flaunt the shamrock in a wrong place you are much mistaken. We have had Irish girls here before, and I have always been able to rely upon them for the maintenance of our high standard. You may go now, Honor, and remove that foolish trimming from your hat; and remember that, as you have been christened 'Honor', I shall expect you to live up to your name."

Honor left the room more subdued than she would have cared to acknowledge. The calm, well-balanced arguments had completely disarmed her. She had entered in a reckless mood, almost anxious to be scolded, that she might have the chance of showing how little she cared; and now, for perhaps the first time in her life, she had been compelled to think seriously and sensibly upon a subject.

Very few teachers would have taken the trouble to reason thus with a pupil, but Miss Cavendish had her special method of education, and believed in paying particular attention to each girl's individuality. "Different plants require different cultivation, if you are to obtain good results," was one of her axioms. "You cannot successfully grow roses and carnations with the same treatment." She had seen at once, partly from her own observation and partly as the result of a talk with Major Fitzgerald, that Honor was an unusual and difficult character; and she wished to obtain a hold over the girl's mind from the very outset. It was part of her system to train her pupils to keep rules rather from a recognition of their justice and value than from a fear of punishment; therefore she regarded the ten minutes spent in the study as, not wasted time, but an opportunity of sowing good seed on hitherto neglected ground.

Vivian Holmes was waiting for Honor outside the door of the study. After conducting her to the school dressing-room, she produced a pair of scissors and ripped the offending green trimming from the hat in stony silence.

"May I keep them?" Honor ventured to ask, for it went to her heart to see her bunch of cherished shamrock torn ruthlessly from its place and flung aside.

"As you like," replied Vivian, "so long as they are not seen here again." Then, with a look of utterly crushing scorn, she burst out: "You needn't think that what you have done is at all clever. It's not the place of a new girl to show off in this way, and you'll gain nothing by it. I am responsible for St. Chad's, and I don't mean to have this kind of nonsense going on there; so please understand, Honor Fitzgerald, that if you give any more trouble, you may expect to find yourself thoroughly well sat upon!"

CHAPTER IV

Janie's Charge

The four-leaved shamrock having so far belied its reputation, and brought bad luck instead of good upon its wearer, Honor put it away in her drawer, with the resolve not to test its powers again until she was back in her own Emerald Isle, where, perhaps, it could exercise its magic more freely than in the land of the stranger.

Her first day at school was satisfactory, in spite of its bad beginning. She took her place in her new class, and made the acquaintance of Miss Farrar, her Form mistress, and all the seventeen girls who composed the Lower Third Form.

After the quiet and solitude of Kilmore Castle, to be at Chessington College seemed like plunging into the world. It was almost bewildering to meet so many companions, all of whom were busily occupied with employments into which she had not yet been initiated. It was an especially fresh experience for Honor to belong to a class, instead of learning from a private governess, and she much appreciated the change. It interested her to watch the faces of her schoolfellows, and to listen to their recitations, or their replies to Miss Farrar's questions. The strict discipline of the place astonished her: the ready answers, the total lack of whispering, the way in which each girl sat straight at her desk, giving her whole attention to the subject in hand; the prompt obedience, even the orderly manner of filing out of the room for lunch, all were as unusual as they were amazing to one who had hitherto behaved as she liked during lessons. She felt for the first time that she was a unit in a large community, and began to have some dim perception of that esprit de corps to which Miss Cavendish had referred during their interview in the study.

In spite of her previous laziness and neglect of work, Honor was a very bright girl, and she contrived even in that first morning to satisfy Miss Farrar that she was capable of doing well if she wished. Perhaps, after all, the four-leaved shamrock had sent her a little luck, for she happened to remember a date which the rest of the Form had forgotten, and won corresponding credit in consequence. When one o'clock arrived she arranged her new textbooks and notebooks in the desk that had been allotted to her next to Lettice Talbot.

"Did you get into a fearful scrape with Miss Cavendish, Paddy?" whispered the latter eagerly. "Do tell me about it!"

But Honor pursed up her mouth and looked inscrutable. She was unwilling to divulge what had passed in the study, and Lettice's curiosity had perforce to go unsatisfied.

On her arrival at St. Chad's Honor had been given a spare cubicle in the bedroom occupied by the Talbots and Pauline Reynolds. On the following afternoon, however, Miss Maitland sent for Janie Henderson, a girl of nearly sixteen, and informed her that a fresh arrangement had been made.

"I am going to put you and Honor Fitzgerald together in the room over the porch," she said. "I hope that you will get on nicely, and become friends. I want you, Janie, to have a good influence over Honor, and help her to keep school rules. She does not yet know our St. Chad's standards, and has very much to learn. I give her into your charge because I am sure you are conscientious, and will try your best to make her wish to improve and turn out a worthy Chaddite. You may carry your things into your new quarters during recreation-time."

"Yes, Miss Maitland," answered Janie, with due respect. She dared not dispute the mistress's orders, but inwardly she was anything but pleased. She did not wish to leave her present cubicle, and looked with dismay at the prospect of having to share a bedroom with this wild Irish girl, towards whom as yet she certainly felt no attraction.

Janie Henderson had a painfully shy and reserved disposition. Hitherto she had made no friends, invited no confidences, and "kept herself to herself" at St. Chad's. She was seldom seen walking with a companion, and during recreation generally buried herself in a book. Slight, pale, and narrow-chested, her constitution was not robust; and though a year and a half at Chessington College had already worked a wonderful improvement, she was still far below the ordinary average of good health. She was a quiet, mouse-like girl, who seldom obtruded herself, or took any prominent part in the life of St. Chad's—a girl who was continually in the background, and passed almost unnoticed among her schoolfellows. She had little self-confidence and a sensitive dread of being laughed at, so for this reason she rarely offered a suggestion, or an opinion, unless invited. She often felt lonely at school, but her shyness prevented her from making advances, and so far nobody had offered her even the elements of friendship. It sometimes hurt her to be thus entirely ignored and left out, but she had grown accustomed to it, and, shutting herself up in her shell, she followed the motto of the Miller of Dee:

"I care for nobody, no, not I,

Since nobody cares for me."

She was obliged to share in the daily games, which were compulsory for all; but she never joined in the voluntary ones unless she were specially asked to do so, to make up a side, and then she played with an utter lack of enthusiasm. "Moonie", as the girls called her, was a bookworm pure and simple. She had read almost every volume in the school library; it did not matter whether it were biography, travels, poetry, essays, or fiction, she would devour any literature that came her way. She lived in an imaginary world, peopled by heroes and heroines of romance, who often seemed more real to her than her schoolmates, and certainly twice as interesting. Half the time she went about in a dream, and even during lesson hours she would let her thoughts drift far away to some exciting incident in a story, or some mental picture of her own. It appeared as if Miss Maitland could not have picked out two more opposite and unsuitable girls to share a bedroom than Honor Fitzgerald and Janie Henderson; but she had good reasons for her choice. Not only did she hope that Janie's sober ways would steady Honor, but she also thought that Honor's high spirits would have a leavening effect upon Janie, who was sadly in need of stirring up.

"I wish I could shake the pair in a bag!" she confided to a fellow-teacher. "It would be of the greatest advantage to both."

There was at least one compensation to Janie for being obliged to change her quarters. No. 8, the room over the porch, was a special sanctum, much coveted by all the other Chaddites. It was arranged to accommodate only two, instead of four, and was the beau-ideal of every pair of chums. It had a French window opening out on to a tiny balcony, and, having been originally intended for one of the mistresses, was furnished rather more luxuriously than the rest of the bedrooms. There was a handsome wall-paper, a full-length mirror in the wardrobe, a comfortable basket-chair, and also what appealed particularly to Janie—a large and inviting bookcase, with glass doors. She conducted her removal, therefore, with less dissatisfaction than she had at first anticipated.

"I call you lucky," declared Lettice Talbot. "I only wish I could go instead. Everyone on our landing is envying you. I shall be rather sorry to lose Paddy—I think she's a joke."

"Especially as we're to have Flossie Taylor instead," said Pauline Reynolds. "It's a poor exchange. I can't stand Flossie; she gives herself airs."

"She needn't put them on with us," observed Maisie. "I've had a quarrel with her already. She was actually trying to make Lettice pick up her balls for her at tennis!"

"Lettice always picks up yours," suggested Pauline.

"That's a totally different matter," declared Maisie.

"I wish Miss Maitland would have let Flossie join the Hammond-Smiths," said Lettice. "I can't imagine why she is making such changes. Oh, here's Honor! Do you know, Paddy, you have got notice to quit?—in fact, you're going to be evicted from No. 13."

Honor had already been informed of the fact by the house-mistress herself. She appeared to take the news with the utmost sangfroid.

"I don't care in the least which room I have," she replied. "All I bargain for is a room-mate who doesn't use 'cold pig' in the mornings. I haven't forgotten your wet sponge."

"You ungrateful Paddy! It was for your good."

"If you call me Paddy I shall call you Salad!"

"You can if you like. It's rather a pretty name, and has a juicy, succulent sound about it."

"Make haste, Honor, and clear your drawers," grunted Maisie. "Here's Flossie Taylor coming down the passage with her arms full of under-linen."