« back

|

GOLDEN MOMENTS BRIGHT STORIES FOR YOUNG FOLKS FULLY ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON DE WOLFE, FISKE AND COMPANY 361 and 365 Washington Street |

SOPHIE'S ROSES.

Froulein Hoffman always gave the girls at her school a holiday on the tenth of June. It was her birthday; and though the old lady would not allow her pupils to make her any presents, saying, in her firm manner, "Such things speedily become a tax, my dears," yet she was always pleased that they should decorate the schoolrooms in her honor, and hang a handsome wreath round her father's picture.

So on the evening before the birthday the day-girls would bring baskets of flowers, and the big schoolroom table was brought out into the garden, and there the wreaths and garlands were made amid much chattering and laughing by the happy children.

"There," said Marie Schmidt, with a satisfied smile, as she held up a large wreath for general admiration. "That's finished at last! and I flatter myself that the old gentleman never had so handsome a decoration in his lifetime as I have now made for his picture."

The girls laughed; but gentle Adela Righton, the only English girl at the school, said quietly, "Take care, Marie; Froulein Hoffman might hear you, and it would hurt her feelings to think that we were laughing at her father."

"I don't want to laugh at any one, you sober old Adela," returned the reckless Marie. "I only think the old gentleman's hooked nose and beady black eyes will look very well under my wreath of lilies and roses."

Adela said no more, for she saw that her words only excited Marie; and fortunately at that moment a diversion was created by a girl coming into the garden with two immense baskets of cabbage-roses and white moss-buds.

"What! more flowers? Why could you not bring them sooner, you tiresome girl?" exclaimed Lotta, who, having finished her garland for the schoolroom window, was more inclined for a romp than for any other flower-wreathing.

"Throw them away! bury them in a hole!" said impetuous Marie, getting up and shaking the petals off her dress. "We've done the wreaths now, Sophie, so your flowers have come too late. I'll tell you what, though: we might fasten a rose to the end of Fanny's pig-tails, and then they would indeed be rose-red."

"No, thank you, Marie: I prefer my pig-tails unadorned," said Fanny good-temperedly, for she was accustomed to jokes on her red hair.

"Throw the flowers on the grass, Sophie! we really can't begin again now!" declared Marie. "I'm going to teach the girls a new game. Now, children, stand in a row. Now hold out your frocks and sing with me." And Marie, leaning against a tree, proceeded to give her orders, and, being somewhat blunt, did not notice the grieved look on Sophie's face as she thought of her wasted flowers.

"Poor roses!" said Adela kindly, noticing Sophie's discomfiture. "They are too sweet to be wasted. May I use them as I like, Sophie?"

"Oh, yes, dear Adela!" said Sophie, brightening. She was a fair, pretty child, with a shady hat tied under her dimpled chin; and seeing Adela stooping to pick up the despised flowers, her spirits rose, and she joined the others in their game under the tree, and danced and sang with the rest.

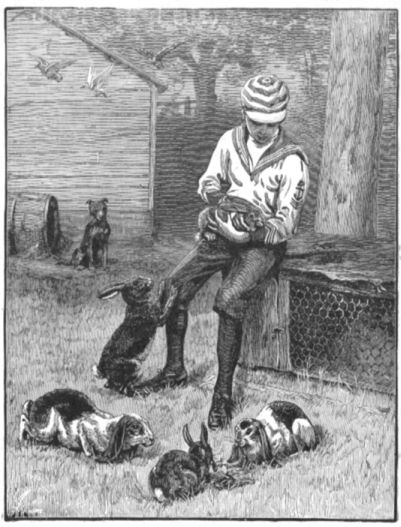

MARIE TEACHES THEM A NEW GAME.

When Froulein Hoffman went early the next morning, as was her yearly custom, to deposit a wreath on her father's grave, she found, to her surprise and intense delight, that some one had been before her.

The grave was literally covered with sweet rose-petals, and round the border, in white rose-buds, were the words,—

"Not lost, but gone before."

Her heart was full to overflowing at this kindly act, and at breakfast, in the gayly-decorated room, she made the girls a little speech.

"Dear girls, you are all young, and have still your friends and relations with you. Mine are all now in God's keeping, but it is very sweet to me to believe that they who loved me so well when on earth still think of me in Heaven. You have helped me to realize this by your tender care of my dear father's grave, and in his name and my own I thank you."

There was silence for a minute or two, for the old lady's speech had moved even the giddy Marie. Then Sophie pressed Adela's hand, and whispered gratefully, "My roses went to decorate God's garden; that is best of all."

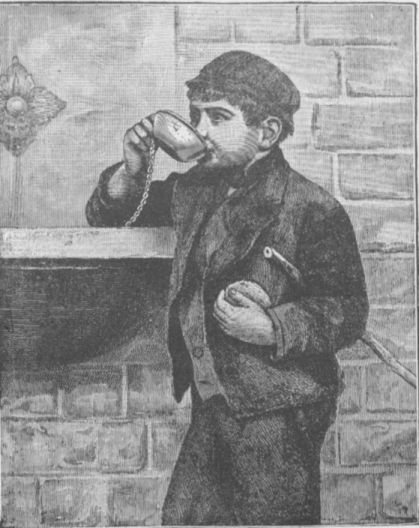

"GOOD MORNING"

MARY'S PIGEONS.

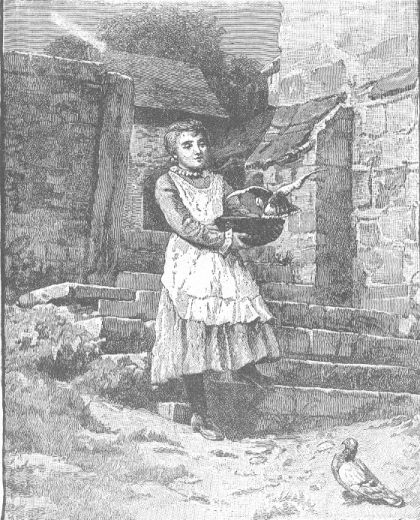

I can't believe there are prettier pigeons than mine anywhere in the world. Every morning and every afternoon I feed them myself, and they are so tame they eat out of my hand, or out of the basin when I hold it for them.

There is some one else who thinks them as pretty as I do, and I'll tell you all about her. It was last year, early in the autumn, that I went out with the pan into the front yard to feed them, and walked down the stone steps, calling the pigeons all the way, while they flew after me. I didn't notice anything in the road, which was just in front of me, until I saw a very big man in a grand livery picking his way across the yard, and then I noticed a carriage had stopped in front of the house, and the lady inside was looking at me and at my pigeons. She beckoned me to come to her; but I was too shy, and ran into the house, to find Mother, who went out to the lady, and I followed just behind her.

And what do you think the lady wanted? To buy my pigeons—my beautiful pigeons! She offered me a dollar, and then two, and then three; but I shook my head every time, and hugged the pigeon that was in my arms. At last she showed me five dollars in gold, and asked if I would let them go for that. But I couldn't—it didn't seem as if any money could pay me for the loss of my pigeons.

Mother said I must do as I liked about it, for they were my very own, but she said five dollars was a great deal of money, and more than the pigeons were worth; only I didn't think so.

Then the lady said she wouldn't ask me any more, but in case I changed my mind she would give Mother her card. I was sorry I couldn't let her have my birds, but then I dare say she has lots of pretty things, and I have only my pigeons.

Well, Father and William laughed at me for some time about the pigeons; and if I wanted any money for shoes or anything, Father would say, "Dear me! how well Mary's five dollars would have paid for this!" But that was only laughingly, for he would never have taken my money.

This spring my pigeons made a nest, and there were two eggs in it, and after a time two birds, that grew just like the others. I was thinking about the lady one day, and I thought, as I had refused to sell her the old birds, I had better offer to give her the young ones. So next day William carried them over in a basket, and left them at the house.

A few days after, the carriage stopped again before our house, and this time the lady came in and sat in the parlor, and ate a piece of Mother's cake and drank a glass of new milk. But before she went away she gave me a parcel which she said was for my very own, and she hoped I would take as good care of it as I did of my pigeons. And when I looked there was the most beautiful work-case in the world! I used not to like my sewing, but now I do, because I use the work-case and the silver thimble every time!

A CAGE STORY.

Now, Pussy, don't turn away and look sulky. I've only put you in Polly's cage so that you may understand a real true cage story that Uncle Rupert told me last night. He's a soldier, you know, and he wears a red sash, just like mine, only he does not wear it round his waist as little girls do, but across his shoulder.

Well, that's not the story, but this is. Uncle Rupert was in China, where the men wear pig-tails down their back, and it was war time: the English were fighting against the Chinese. He told me why, but I've forgotten, but I know in the end the English won; but they lost a battle first, and Uncle Rupert was taken prisoner. English people are kind to their prisoners, Pussy, but the Chinese are very cruel. Uncle Rupert says he could not tell me the dreadful things that they did to some of the poor English soldiers, but he told me what they did to him, and though it was dreadful it was rather funny too. Listen, Pussy! They made a big cage, only it wasn't nearly big enough, and they shut Uncle up in it, and slung it on a big stick, and carried him about as a show to all the towns and villages. It was very hot, and Uncle was so cramped up in the cage that he could hardly move, and he was very hungry and thirsty, and very, very miserable. The people used to come and stare at him, and tease him by poking nice fruit through the bars, and then snatching it away before he could eat it. Uncle Rupert said he longed to die; but he said one thing, Pussy, which I must always remember, only I'm afraid you won't understand this. He told me how glad he was that when he was a little boy his mother had taught him a great many texts and hymns. They all came into his mind then, and they comforted him very much, and made him remember that God was near him, even in the cage. So he was patient, and at last he was saved, for some English soldiers marched to the village, and the Chinese ran away and left the cage behind them, and you may be sure the soldiers soon got Uncle Rupert out.

GOOD NIGHT.

A THANKOFFERING.

Ada Fortescue was recovering from a long and dangerous illness, and for the last week she had been able to lie on a sofa near the window, and see the people passing through the street as they trudged on their way to the city. Ada was twelve years old; and as she lay on her sofa she had many thoughts, some very serious, but most were happy and grateful.

Ada was Dr. Fortescue's only child, and her mother had been dead for eight years. During her illness Ada had often seen how grave her father looked, but now his thankfulness brought tears into her eyes. It was so nice to be loved so very much, thought Ada.

To-day a very absorbing thought was in her mind, and she looked up and down the street with more than usual interest. That morning her father had told her that he had put aside a sum of money as a thankoffering for her recovery, and she might choose the way in which it should be spent. What should she do? Ada thought of the missionaries far away, of the new church close by, of the hospital, and the orphanage.

At that moment a noise in the street attracted her attention. A man was loudly scolding a little boy, who was crying bitterly. The boy looked pale and tired; and Ada felt very sorry for him, so she opened the window to hear what was the matter. The man had come out of his shop, and was saying angrily, "Do you think I have nothing to do but give glasses of water to every vagabond who goes by? Be off with you, and don't stand there crying and making a crowd collect," for some of those who were passing had paused to find out what was the matter.

Ada rang the bell and sent the maid out to the little boy, who came thankfully for some water, only the water was nearly all milk, and there was a bun and a piece of bread for him besides. What a happy little boy he felt, and what a happy little girl was Ada as she met her father at the door of her room, saying, "I know, I know! a drinking fountain, father!"

At first Dr. Fortescue could not understand what she meant, but when she explained he thought it was a very good idea.

Some months later when Ada had a bad cold and was up in her room once more, it amused her to watch her drinking fountain, which was in the opposite wall, and see all the people who drank at it, and she was very glad when one day she recognized the little boy who had first put the idea of a drinking fountain into her head. He had a roll in his hand, and wore a nice tidy suit of clothes; and when Ada sent the maid to inquire after him she heard that he was on the way to see his mother with a quarter's wages in his pocket, for he had got a good place and meant to do all he could to keep it.

ONLY AN OLD COAT.

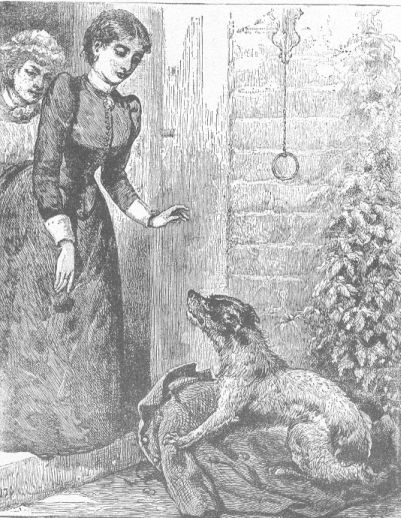

A TRUE STORY OF A FAITHFUL DOG.

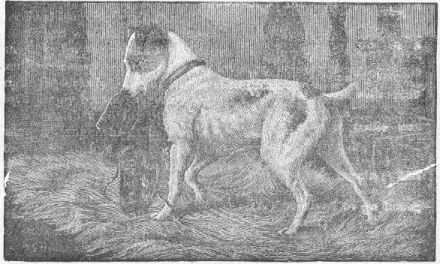

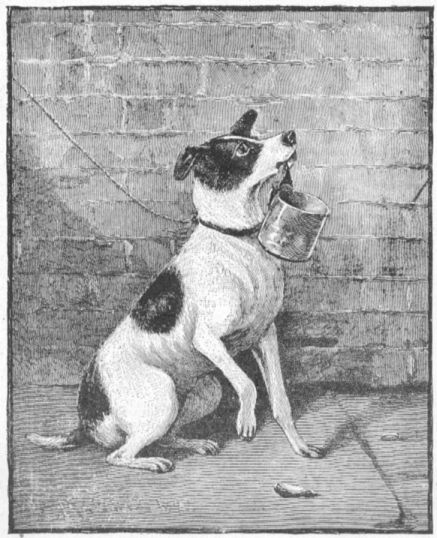

"Only an old coat! That's what it is surely, but that old coat cost me a good friend, it did. Poor old Tinker was worth more than a dozen coats." So said Eli Watton, as he put the old coat over his shoulders, and settled himself in his donkey-cart with a man by his side who had asked for a lift.

"Who was poor old Tinker?" asked the stranger.

"My dog," answered Eli, "and a better one never followed any man. Poor fellow! though he weren't much to look at. Well, I'll tell you how it was I lost him, poor chap. Every Friday I have to drive into town to fetch the clothes for my wife to wash, and I often had to go in again on a Monday with clean ones. Tinker, poor fellow, used to go with me most times, but I never gave much heed to him. He'd always follow without a word. He was an ugly brute, people used to say—a sort of lurcher, and he never got much petting from any one.

"Well, one day I drove as usual, and I had this old coat over the basket of clothes. When I got to one house I suppose I pitched the old coat out, but I never heeded it; and I never noticed whether Tinker was with me or not. That night we missed Tinker; and my wife couldn't think what I'd done with the old coat, and I couldn't remember anything about it.

"On Monday I had to go to that same house, and there I found my poor old Tinker dead; they'd had him shot. I was in a way about it, I can tell you. It was in this way, you see. This old coat was in a doorway, where I suppose I threw it when I was taking down the basket. Old Tinker saw I left it there, and he sat down upon it to keep it safe for me, showing his teeth at anybody who offered to touch it. The servants got frightened; they tried to beat him away, and they tried to coax him away, but he wouldn't stir, and at last they thought he must be mad, and told their mistress. She came and did all she could to coax the dog away, for he was right in the way when they went out or in; but he snarled at them all. He must have been pretty near starved, lying there all Saturday night and Sunday, and I dare say he did get fiercer and fiercer, so at last they got him shot.

"I've never had a dog along with me again. I don't suppose I shall ever get one like Tinker. I always think of him when I take up this old coat;" and Eli gave his donkey a cut with the whip, and I am not sure if there was not something like a tear in his eye as he thought of his lost Tinker. What did it matter that he was an ugly dog? He did his duty to the end of his life, and which of us can do more?

|

AMBITION I often wonder how Papa F. Wyville Home. |

THE GOOD AND BAD FAIRIES.

Two houses stood side by side, as much alike as two twins. Honeysuckle and sweetbrier climbed over the rustic porches, flowers bloomed gayly in the gardens, and the warm sun shone equally on both. In each lived a little girl who had an invisible fairy companion. The children were the same size, the same age, and had the same advantages, with this difference, that the one fairy was good and the other bad.

A ray of sunshine glides through the window into the first house, and shines encouragingly on little Minnie, who is trying to do her lessons.

But the bad fairy has set her pygmies to work. One persuades her that she will do her lessons better if she sits in an easy-chair, another puts a cushion at her back, while a third fans her face so gently that the soft breeze, fragrant with honeysuckle and sweetbrier, soon sends her off to sleep, but not to rest. To her dismay the pygmy sweep comes round the corner, and with his sooty brush sweeps the pages of her new atlas. The coalheavers turn over her inkstand upon it, and the black fluid comes streaming down. Aunt Susan's sharp voice calls out, "Mind your dress, you naughty child."

Minnie puts her hand across it; but the fireman quickly pulls aside the table-cloth, runs his finger down the stream, and her lap is a pool of ink.

"Won't you catch it?" says an old woman, with a delighted chuckle; and the pygmy under the table crawls out, grinning with pleasure.

"We can take the horse to the water, if we cannot make him drink," shouts a newsboy in her ear; and with a great deal of tugging and thumping she feels herself driven closer to her books. But idle hands make an idle brain, and the pages seem only a blank.

"How long wilt thou sleep, lazy one?" cries a grave face in spectacles and lawns. With a sleepy feeling she turns her head away from his stern gaze, only to meet the sterner faces of the judges, who are examining her untidy copy-book.

"Not a single line written this morning. What have you to say in self-defence?"

"Please, sir, the acrobat had my pen balanced on his nose," said Minnie feebly.

"An excuse is worse than a lie," answered one of the judges; "for an excuse is a lie guarded." The book closed with a bang, and the judge marched off to consider the verdict.

At this moment Minnie started up in a fright, to find the dinner-bell ringing, the inkstand upset in her hurry, and no lessons done.

And now she had to go and wash her hands and make herself tidy for dinner. What would mother say when she came to know how little Minnie had done that morning?

A ray of sunshine shone through the window of the second house also, and softly kissed the rosy cheek of little Winnie, as she lay sleeping in her cot.

"Get up," said a small voice in her ear: "it is your turn to arrange the schoolroom to-day."

Winnie jumped out of bed, and was dressed in less than no time; for the good fairy had set her train to wait on her. Her shoes were placed ready to her feet, her strings did not get into knots, and even her hair was not tangled.

Running down into the schoolroom, and tying on a large apron, she set to work to polish the mahogany cupboard with so good a will that Jack Tar, who stood above it, fairly clapped his hands with glee. Two neat little maids swept the floor, and two little men with their tiny brushes took up the dust. The highest shelf in the book-case was soon mounted by one of the pygmies, whilst two on the next shelf dusted and handed him the books. The carpet-cleaner stretched and nailed down a corner of the drugget which had been kicked up. The coachman, footman, butler, and buttons stood in readiness to carry out the orders of Policeman X. It was a good thing Policeman X was there; for quite a crowd had collected to see the work so briskly going on. The three little pygmies climbed up the rail of a chair to beeswax and polish it. A bookbinder sat cross-legged on one corner, arranging the loose leaves of a book; and a fat cobbler sat balanced on the rail below, singing, "A stitch in time saves nine."

The work was soon done; and when Aunt Susan came into the room she praised little Winnie, and said the white hen had laid her an egg for breakfast.

Now, perhaps, you would like to know the names of the two fairies who attended the little girls. The good fairy was called Work-with-a-will; the bad fairy, No-will-to-work.

HELPING MOTHER

It was a lovely summer's day; there was a hot sun with a nice breeze, and Mrs. Jones, who had a heavy wash on her hands, was delighted.

"I shall get all dried off before night," she exclaimed, as she hung out the snowy sheets, and the children's shirts and pinafores, which latter looked rather like doll's clothes as they hung on the line beside father's great stockings.

Tommy and Jeannie, of course, were there too, and very busy, as they had taken it into their heads to plant all the clothes-pegs they could lay hands upon, under the idea that they would soon grow into cabbages!

"Dear! dear!" exclaimed poor Mrs. Jones, when she turned round, having filled the line, and found out what her children had been after. "Did any one ever see such children? I must get them away from the wash somehow. See now, duckies, I'll get you some cherries off the tree, and you'll play pretty on the bench, and let mother get on with her work, won't you?"

"Yes, mother, we'll be ever so good," declared Tommy; and Jeannie, who could not speak plainly, echoed solemnly, "Never good!"

So Mrs. Jones fetched a ladder and gathered some juicy cherries, and for a long time the children played with them happily enough. First of all Tommy kept a jeweller's shop on the old bench, and sold cherry earrings to Jeannie, who tried to fasten the double cherries on to her fat little ears. Then she kept shop, and sold cherry boots to Tommy, and then they got the doll's perambulator and wheeled the cherries to market, and then Tommy said it was time to eat the cherries, and he divided them fairly, and soon ate his share up. But what a mess he did make of his hands and face! they were stained black with cherry juice. "Never mind!" said Tommy calmly, "I'll soon wipe it all off;" and catching hold of a sheet which hung on the line near, he first rubbed himself quite clean, and then gave Jeannie's hands a rub, too, on this most convenient towel. Not till he had finished, and the sheet was again flapping in the wind, did thoughtless Tommy reflect on the mischief he had done. But when he saw the purple stains on the clean sheet he began to cry bitterly, and running to his mother, he pulled her round and showed her the cherry-stained sheet.

"Look, mother! look! But I didn't mean to," he sobbed.

"Mothers," says an old writer, "should be all patience," and certainly Mrs. Jones needed patience that morning. She did look vexed at first, as she saw her work undone, but the next minute she was able to say gently, "What a pity, Tommy! You should think a bit, and then you would be able to help me when I'm busy," and that was all. She took the sheet down and put it once more in the wash-tub.

Meanwhile Tommy sat quietly sucking his thumb. He always sucked his thumb when he thought, and just now he had a great deal to think of. Mother had said he might help her! That was quite a new idea to Tommy, and he sucked his thumb harder than ever.

That summer's day marked a turning point in Tommy's life. He then determined—little fellow as he was—to help mother, and it was wonderful how soon the thoughtless little pickle grew into a helpful boy.

"It seems as if he couldn't do enough for me," Mrs. Jones would declare, with honest pride in her tone; "and Jeannie, she copies Tommy, and between them both they'll fetch and carry and run for me till I seem as if I had nothing left for me to do. I'm a lucky woman, that I am!"

|

Little Sister

Sleep, little sister, a sweet, sweet sleep, E. Oxenford. |

"LITTLE ME."

I cannot tell how she came to be called "Little Me." She was a shy little girl, and almost afraid of her own voice; though to hear her playing with her brothers you would not have fancied that she was shy. And now they were on their way to the country. There was Emma the nurse, and Miss Brown the governess, Little Me, Tommy, aged seven, and Jack, aged ten. There was first a long journey in a cab, with many boxes; then a long journey in a train very full of people.

It seemed to Little Me as if that train had been going on all the day, and the sandwiches and milk which nurse had in a little hamper tasted quite warm; and Little Me's legs ached from dangling from a seat too high for her feet to reach the ground, and at last she fell asleep.

She awoke suddenly with a start to find every one turning out of the train, and she felt cross and inclined to cry, but there was no time.

"LITTLE ME"

At last all three children, Miss Brown, and nurse were safely packed into a carriage which was waiting for them. The luggage came behind in a cart.

Little Me was really tired, so nurse put her to sit on a soft rug at the bottom of the carriage. Here she could just see green trees overhead, and the tops of green hedges, and soft white clouds turning to gold and red, as the sun set behind some hills in the far-off distance.

They reached at last a pretty cottage, with a thatched roof and a white wall quite covered with red roses. There was a little path of round stones leading up to the front door, and all the windows had small diamond panes.

A stout old lady, in a spotless white cap with pink ribbons, met them at the door, and took Little Me in her strong arms and carried her up some narrow stairs into a bedroom with white curtains to the bed and windows, and white walls.

After a good wash Little Me felt quite wide-awake, and very hungry, and was glad to be taken down to tea.

It was a delightful tea! There were tiny little loaves for each of the children, home-made cakes with plenty of plums, and strawberries and cream, and ducks' eggs. These the farmer's wife showed Little Me had pretty pale green shells, instead of white or brown like the hens' eggs, and Mrs. White promised to show the children some baby chickens and ducklings the next day.

How Little Me did sleep that night, to be sure! She never heard her father and mother and Bob, her elder brother, arrive at all; and it was eight o'clock before she woke the next morning, and found they had all gone out and left Me in kind Mrs. White's care. Mrs. White took her to feed the chickens—such dear little fluffy balls of yellow and white and black down, and Mrs. White let Little Me feed them out of a saucer, and some of them jumped over Me's hand, and were most friendly; and then Mrs. White took her to a pretty pond, and showed her a beautiful duck and nine baby ducks, not so fluffy and small as the chickens, but yet very soft and clean-looking.

Bob was rather too grown up to play much with Little Me, and Tommy always played with Jack, so that Little Me spent much of her time wandering about by herself.

The pond where the duck and ducklings lived had a little waterfall at one end, and then it became a little stream, and ran over pebbles under a bridge, and wandered away into the fields with a border of forget-me-nots.

Little Me was very fond of this stream, and one day Tommy persuaded her to take off her shoes and socks and walk through the stream with him. This was very delightful; but when they were just in the middle of the stream there came in sight some cows, and a boy and man driving them.

Now, if there was one thing Little Me dreaded more than another it was cows; and her ideas of propriety were greatly shocked at the idea of a strange man and boy seeing her bare feet, so she raced back to her shoes and socks, picked them up, and tumbled over a stile as fast as her short, fat little legs could go, and hid behind a hedge, all out of breath.

There poor Little Me crouched till she heard the last slow step of the last cow plash through the stream, where some of them stopped to drink, and the sound of voices died away over the bridge; then in much hurry and alarm she thrust her wet little feet into her damp socks, which she had in her fright dropped into the water, and the wet feet and socks were hastily put into the shoes, and Little Me again climbed the stile to join her brother, to whom she was ashamed to own that she had been afraid of the cows.

Being a city child, and not a very strong one, Little Me was unused to wet feet, and she caught a bad cold, which ended by her spending many days in bed; but the boys brought her flowers, and Mrs. White made her many little loaves and cakes, and gave her honey and cream, and altogether Me thought being ill at a farmhouse much better than being well in the city.

OSCAR AND BRUNO.

When we were living in a very remote part of Northumberland, in an old house that had once been a monastery, we had two large dogs named Oscar and Bruno.

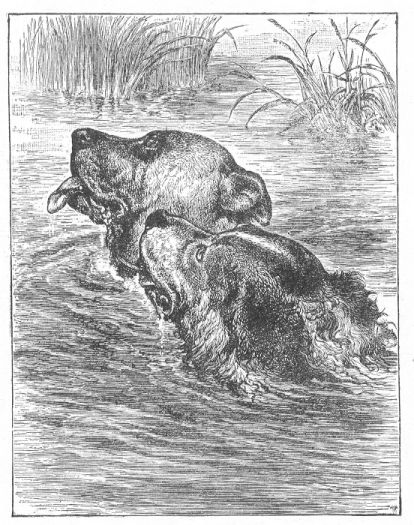

Oscar, who was a Newfoundland with a bit of the retriever in him, had been especially trained to take the water and to secure the game when shot among the deep pools.

Bruno, on the other hand, was a huge mastiff, who was kept to guard the house; gentle and docile to those whom he knew, but woe betide the suspicious-looking stranger who approached the house—his growl was enough to frighten the stoutest-hearted beggar in the world.

My father thought Bruno was getting a little lazy, so proposed to take him down to the river with Oscar. I was to accompany them, and see poor old Bruno have a bath.

The river was not very broad, narrow enough to be spanned by an old wooden bridge, but it was very deep in the centre.

Bruno floundered about, and at last got into the deep centre current, and, to my horror, I saw he was losing strength and sinking. I shouted to father that Bruno was drowning. He called to Oscar, "Save your friend, Oscar!" And the faithful creature seemed to grasp the situation, for he swam out to Bruno, and taking hold of his strong leather collar between his teeth, he lifted his head and shoulders out of the water. I eagerly watched them, for Bruno was very heavy, and it looked as if poor Oscar would not have strength to land his friend.

Father encouraged Oscar, for I saw the fear in his face too; and making one supreme effort, struggling and panting, Oscar brought Bruno into shallow water. In a few minutes Oscar was all right, but poor old Bruno was long before he came to himself. His devotion to Oscar after that was beautiful to see, and they were firmer and truer friends ever afterwards.

A LITTLE KNOWLEDGE.

Tom was one of those boys who, being fairly quick and clever, think they know everything and can do everything without being taught. Now, however quick and clever a boy or girl may be, this is a great mistake, because it is wiser and safer to profit by the experience of an older person than to learn by one's own experience. But Tom always knew beforehand anything that his father or mother could tell him; and the result was that he often found himself in the wrong, and more than once suffered for his conceit and self-sufficiency.

Tom had lived in London all his life, with only occasional visits to the seaside and a few days in the country at Christmas, when his father and mother usually went on a visit to his uncle's house at Felford. He was therefore much excited when at breakfast one morning, just after the Midsummer holidays had begun, his mother handed a letter across the table to her husband, asking, "What do you think of that?"

Tom's quick eyes saw that the writing was his uncle's. He watched, and saw his father and mother both glance at him.

"Well, Tom, I see you have your suspicions about this letter," said his father; "and you are right. It does concern you. Your uncle has asked you to go to Felford. Your aunt and the little ones will be away; but your uncle will be at home, and Allan will be there to keep you company. Now, do you think you can be trusted to go alone, and not give your uncle any trouble, or lead Allan into mischief?"

"Why, of course, Father!" Tom answered readily.

"I am sorry to say there is no 'of course' in the matter; but you can try this once, and I hope it may be as you say. But you must remember that your uncle is very strict, and that you will not be allowed"—

"Oh, I know!" said Tom, but his father stopped him.

"If you say that to me again I shall not let you go to your uncle's. If you know so well, you ought to practise what you know, and give less anxiety to your mother and me."

At last the day came. His father saw him off at the station; and, after a journey of two hours, Tom arrived at the Felford station, and found his uncle's wagon had come to meet him, and Allan was in it. The boys had much to say to each other; for they had not met for some months, and were always good friends, Allan being only eight months younger than Tom. Allan had much to tell of their plans for enjoyment while Tom was at Felford, and among other pleasant things, there was to be a village cricket match, in which Allan was to play.

"And you, too, Tom," he said, for he never doubted his cousin's powers. "It won't be a very grand match, you see, but it will be capital fun, and the boys play"—

"Oh, I know!" said Tom.

"All right: that will be capital," said Allan; and Tom, who had never held a bat in his life, found himself engaged to play in the match.

"But I shall find it quite easy," he thought. "I've seen it played, and the boys at school seem to find it simple enough."

His uncle was out riding when Tom reached Felford, having had business to attend to, so the boys at once went out into the garden and inspected the scene of the future cricket match.

Tom looked at it a moment, then visions of Lords came before him, and he said decidedly, "It wants rolling dreadfully!"

"Father said it was too dry to roll," said Allan, in rather a melancholy tone. "You see, if"—

"Oh, I know!" interrupted Tom; "but we might try to roll it ourselves, don't you know. That would be fun, and it would surprise him. Is there a roller anywhere?"

"Yes, the small garden-roller; but Father said"—

"Oh, I know!" said Tom impatiently. "Let us fetch it."

Allan said no more. It was clear that Tom did not intend to listen to anything he had to say.

"Do you know how to use the roller?" asked Allan.

"I should hope so! Any one must know that," said Tom; and away they went to fetch it.

Now, there is a right way and a wrong way to do everything, and a garden-roller should be pulled and not pushed, but this Tom did not understand; therefore, he set to work with Allan to push the roller through the garden towards the field, while Twinkle, the fox-terrier, followed at their heels.

A garden-roller is an awkward thing to manage if you don't understand it. The iron handle is heavily weighted, and if pressed down and then released it springs up with great force, owing to the weight with which it is balanced.

Tom knew nothing of this; and Allan had never been allowed to touch the roller, so he was as ignorant as Tom. They had paused to draw breath, when Twinkle's bark of delight made Allan exclaim, "There's Father!"

At that moment Tom took his arms off the iron handle on which they had been resting, and the handle sprang up. There was a cry from Allan, and Tom saw to his horror that one end of the iron bar had struck the boy just above the eye. It was a painful blow, and the bruise began at once to discolor and swell, so that by the time his father came up poor Allan was a piteous object.

It was a most unfortunate beginning to Tom's visit. Of course his uncle was angry, for the garden-roller was quite useless for the purpose of rolling the field, and the ground was so hard and dry that no rolling, even with the heaviest horse-roller, would have done any good. Allan was very sorry for Tom, and took more than a fair share of the blame, saying he ought to have been more careful; but he was rather distressed when he found that he had a black eye, and that it could not be well before the cricket match, when the boys would be sure to chaff him.

This exploit of Tom's and his uncle's anger made the boy more careful; and all went well until the day before the cricket match, when Tom and Allan went out for a private practice in the field.

"You aren't standing right. Your leg's before the wicket," said Allan, as Tom stood ready, bat in hand, to receive the ball.

"Oh, I know! but it's only for practice," said Tom quickly. "Send me the ball."

Allan bowled, Tom hit, the ball spun straight up in the air and came down almost at Tom's feet.

"Hullo!" said Allan, pointing to the stumps; "how did you do that?"

Tom looked round and found he had knocked over the stumps. This slight mistake having been set right, Tom was ready to start again. This time, as the ball spun off his bat, there was a crash, and Allan exclaimed in horror, "Oh, Father's precious orchids!" for the ball had gone through the glass of the small greenhouse, and had overturned and injured several cherished plants.

Poor Tom thought he had had enough of cricket for that day, and went in to make his confession to his uncle. Allan's piteous face did more towards softening his father than Tom's regrets, and he said very little about the matter, though possibly he felt the more.

The next day the cricket match came off. Tom very soon found that in playing it was necessary to have done something more than look on. He knew little or nothing of the rules of the game, and brought disgrace on himself, and on his cousin for having introduced so bad a player into the village eleven. Had there been any one to take his place he would have been turned out in spite of anything Allan could say, but as it was they were obliged to put up with him.

When Tom went in, his first action was to put himself out, amid the hootings of fury and amusement of the rest of the party. Even Allan was getting cross with him.

When the other side went in again, Tom made more effort to follow the game and catch the ball; but he knew nothing of cricket, and was wearing his ordinary walking-boots. The grass was dry and slippery, and Tom was clumsy. He was chasing the ball, and thought he should really succeed in catching it this time, when his foot slipped and he fell heavily on the grass. He had broken his leg!

The boys who had laughed before were now full of sympathy. He was at once taken into the house and the doctor sent for. What poor Tom suffered for the rest of that day and all the night, only those who have broken a leg can tell, and added to his pain was the feeling that he had shown all Allan's friends what a boastful fellow he was.

|

The Swallows' Song.

"Tweet! tweet! tweet!" the swallows say, E. Oxenford. |

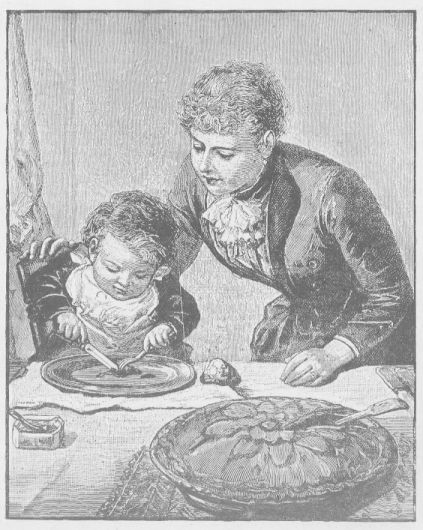

HIS FIRST KNIFE AND FORK.

Stevie could hardly believe his eyes. But it was true, quite true, all the same for that, and he opened his blue eyes wider and wider till mother laughed and kissed them, and lifted him up into his high chair, saying, "Yes, Stevie, they are yours, your very own, and grandpa sent them to you because he remembered your birthday." Such a beautiful, sweet-smelling leather case it was, lined with purple velvet, and inside it a silver fork with a pretty "S" on the handle, and a knife that would really cut. His first knife and fork! Oh, how Stevie had longed for them! And now that they had come, his very own, he felt quite a man, almost like father.

"Stevie must learn to handle them nicely, ready to show grandpa when he comes. Not that way, pet! Let the back of the blade look up to the ceiling, like little birdies after they drink, and keep the sharp edge down to the plate, and then little fingers won't be cut."

"All alone by myself, mother? all alone by myself?" cried Stevie eagerly; but mother stood beside him till the pie was cut up, and the pretty knife and fork had been laid aside to be washed and put back in their velvet case.

Stevie learned to handle his knife and fork quite nicely in a few days, but he found it rather hard that he was never allowed to have them to play with. He used them at the table and that was all. The day grandpa came Stevie was all excitement to show him how well he could use his beautiful present. Mother had gone to the station to meet him, and it seemed that the long morning of waiting would never be over. But twelve o'clock came at last, and nurse gave Stevie a biscuit and an apple, and sent him out in the garden so that he should not disturb baby's nap. He ran away down to the fountain and began to play dinner. Then he thought of his dear knife and fork. He knew just where they were, but he had been told never to touch them. He did want them so much, and they were his own. The apple would seem just like a real dinner if he only had them. Stevie ran into the dining-room and mounted the chair by the sideboard. For a moment he stopped; for it seemed as if some one said, "Don't touch, Stevie!" quite loud in his ear, but only the clock went "Tick, tack, tick, tack!" There was only the little voice of conscience inside Stevie to say "Don't touch;" and he wouldn't listen to that, so he ran away with the pretty case in his hand.

Stevie played dinner, and old gray pussy sat on the fountain basin and looked at him. She played grandpa, at least Stevie said so; but somehow the apple didn't taste so sweet as at first, and he cut his thumb a little, and thought he would put the knife and fork back. Back in their case he did put them, clip went the little silver fastening, Pussy arched her back and swelled her tail, for the dog belonging to the baker had just come through the gate with his master. There was a rush and a tussle, and the baker ran to Stevie; but something had gone splash! into the fountain, and Stevie ran away crying. How everybody did hunt for that knife and fork, while Stevie sat very pale and quiet, holding one fat thumb hidden by his hand.

Grandpa sat next to the high-chair. "Cheer up, little man: it will be found."

And mother said, "Never mind, pet; it can't be really lost!"

Stevie's thumb hurt him, and he felt so miserable that he couldn't bear his trouble "all alone by himself" any longer, so he sobbed out, "'Tisn't lost! it is in the fountain! Wanted it all by myself!"

Mother took him on her lap till she had made out what had happened. Then she tied up the poor cut thumb while grandpa went down to the fountain and fished up the knife and fork. Stevie ate his dinner with a spoon, for grandpa said he thought the knife and fork had better go away till the poor thumb was well. The pretty case was quite, quite spoiled. But Stevie got his knife and fork back; and we noticed that we didn't have to say, "Don't touch, Stevie!" nearly so often to him, and that he was not nearly so eager to have things "all alone."

|

The Wren's Gift. A little maid was sitting |

VERA'S CHRISTMAS GIFT.

It was Christmas Day, and very, very hot; for Christmas in South Africa comes at mid-summer, whilst the winter, or rainy season, occurs there in July and August, which certainly seems a strange arrangement to our ideas. However, whatever the temperature may be, Christmas is ever kept by all English people as nearly as possible in the same way as they were wont to keep it "at Home," for it is thus that all colonists lovingly speak of the land of their birth.

So, though little Vera Everest lived on an African farm, she knew all about Christmas, and did not forget to hang up both her fat, white socks, to find them well filled with presents on Christmas morning; and there were roast turkey and plum-pudding for dinner, just as you had last year.

She was not old enough to ride to the distant village church with her parents, but she amused herself during their absence with singing all the Christmas carols she knew to Sixpence, her Zulu nurse; and by and by she heard the tramp of the horse's feet, and ran to the door.

Instead of the cheerful greeting she expected, Mother hardly noticed her little girl. She held an open letter in her hand, and was crying—yes, crying on Christmas Day!

Mrs. Everest was indeed in sad grief; the mail had just come in, and she had a letter to say that her mother was seriously ill, and longing to see her. A few months ago there would have been no difficulty about the journey; but the Everests had lost a great deal of money lately, and an expensive journey was now quite out of the question, and yet it cut her to the heart not to be able to go to her mother when she was ill, and perhaps dying.

Vera was too young to be told all this, but she was not too young to see that Mother was in trouble.

"I do believe Santa Claus forgot Mammy's stocking," she said to herself: "she has not had a present to-day, and that's why she's crying."

So Vera turned the matter over in her mind, and came to the conclusion that she must give Mother a present, as Santa Claus had so shamefully neglected her.

She went to her treasure-box—a tin biscuit-case in which she kept the pretty stones and crystals which she picked up in her walks, and, after thinking a little, she chose a bright, irregular-shaped stone, and, clasping her hands tightly behind her, she went on to the veranda.

Mother was lying back in a cane chair and gazing with sad eyes over the sea.

"I've brought you a Christmas present, Mother," said Vera. "Don't cry any more, but guess what it is."

Mrs. Everest turned round and smiled lovingly at her child. Certainly little Vera made a pleasant picture for a mother's eyes to dwell upon as she stood there roguishly smiling in her cool white frock and blue sash, and a coral necklace on her fat neck, whilst her golden hair shone like a halo round her head.

"Guess, Mother dear," repeated Vera; then, unable to wait, she jumped on Mrs. Everest's lap, and, opening her little pink hands, she displayed the stone. "It's your Christmas present!" she declared.

Mrs. Everest kissed the child, but did not, so thought Vera, take enough notice of her handsome gift.

"It shines, doesn't it, Father?" she said, holding it up for Mr. Everest's inspection as he passed along the veranda.

Mr. Everest stopped, took the stone in his hand, then, turning deadly pale, he walked quickly into the house without saying a word. Vera felt the world was somewhat disappointing to-day; but in a minute or two her father reappeared, and hastily encircling both wife and child with his arm, he said gayly, "There, Sophy! kiss your little daughter, and congratulate her. She has made your fortune, and you can leave for home to-morrow, and engage a state cabin if you like."

"O Henry! what do you mean?" said the bewildered Mrs. Everest.

"Just what I say!" he declared. "Vera's gift to you is a diamond; and if I know anything, it will sell in Capetown for a good round sum. So don't fret any more, little woman, but pack up your traps and take your clever daughter with you, and we will start for Capetown to-night, so as to catch the first steamer for home."

Vera could not now think that her present was not enough appreciated, for Father would not let it out of his hand until he got to the jeweller's at Capetown, and had sold it for a large sum of money.

Vera and her mother sailed the very next day, and Grandma got better from the hour of their arrival. As for Mother, she was now always smiling; for with Grandma well, and no debts to worry her, she felt so happy that she seemed hardly to know how to be grateful enough.

Certainly there could not have been a more opportune present than Vera's Christmas Gift.

TOMMY TORMENT.

We all called him in private "Tommy Torment;" but his mother called him "My precious darling," and "My sweet, good boy," and spoiled him in a truly dreadful way. Anyhow, he was not a nice boy, and we never saw more of him than we could help.

He did not go to school even, for this seven-year-old boy was thought too delicate, and was taught at home by a governess with sandy curls, who brought books in a needlework bag that we all used to laugh at—I am sure I don't know why; but her teaching could not have amounted to much, for I went into the schoolroom one day, and found Tommy riding defiantly on the rocking-horse, while poor Miss Feechim stood by him with an A B C in one hand and a long pointer in the other, with which she showed him the letters. When he said them correctly, Miss Feechim gave him a sugar-plum out of the bag on her arm, but when he refused to look at them, which he did as often as not, she only said, "Oh, Tommy!" and shook her curls, and never attempted to make him mind her; and then he laughed and called her names, and rocked his horse so violently up and down that his poor mother came rushing up-stairs white with anxiety to know what was the matter.

You can imagine after this we were not overjoyed when we heard from Mother that Lady Mary was so ill her mother had taken possession of her, and that we were to have the pleasure of Tommy Torment's company at the seaside. Mother said she was very sorry, but she could not help it. The doctor said Lady Mary must have complete rest, and no worries; and Lady Mary had said she could not trust her precious treasure to any one else but Mother. So, when we set off on our annual holiday, Tommy was stuck into a corner of the omnibus.

Well, at first, and under Mother's eye, we really did think we had been rather hard on Tommy Torment, he seemed so like other boys; but presently, when the novelty had worn off, and he had become tired of being good, the real Tommy appeared, and for at least a week we had really what Nurse calls a "regular time of it." There was not a trick he did not know; and the worst of it was that our boys became tricky too, and we really did not know how to bear the rough usage we all received, for we never had a moment's pleasure or peace of our lives; and what with sand in our hair, wet star-fish down our backs, and seeing our dolls shipwrecked in their best clothes off the steepest possible rocks, we never felt secure for a moment, and we actually began to wish ourselves back in the city, when Nurse fortunately rose to the occasion, and, taking the law into her own hands, escorted the whole party up to Mother, which brought matters to a climax; for our boys were so ashamed of their cruelty and ungentlemanly behavior when Mother explained to them what their tricks really meant, that they became their own true selves, and we had the first good play together of the season the next morning on the shore, though Tommy did his best to bother us, and to draw off the boys again by promising to show them quite a new way of managing a shipwreck.

But the boys would not join Tommy, and so he went off alone, and we saw him five minutes after with Yellowboy, the sandy kitten, tied to the mast of his ship, doing his very best to drown the poor little thing, pretending he was rescuing it from the perils of the ocean.

I could fill pages were I to go on telling you only of Tommy's tricks; but as that cannot be, I am just going to let you know how we cured him. We simply let him alone. Mother only scolded him, or rather talked to him, once, and that seemed to have no effect on him at all, though Mother's "talkings" usually soften the hardest heart; so finally we all agreed to go our own ways just as if he were not there, Nurse promising to put all our toys and pets out of his reach, and to see that he came to no real harm.

He actually bore a whole week of it before he repented. We used to watch him from the corners of our eyes moping all by himself, and looking at the toes of his boots, or at his ship, which he really could not sail without our help, and felt so sorry for him. We longed to break our resolution; but Mother and Nurse helped us to keep firm, and one Monday morning Tommy came up to me and said, "Why won't you play with me, Hilda?"

"Because you are cruel and ungentlemanly," I said seriously, "and because you are selfish. We tried our best to be pleasant to you, though we never wanted you here, and in return you made the boys horrid to us, and never allowed us five minutes' peace. You spoiled a whole week of our precious holidays, and we can't afford to waste any more time over you. We can do without you perfectly well, and so please go away."

"But I am truly sorry, Hilda," he said, looking down. "I've been 'flecting" (he meant reflecting). "I'd much rather be agreeable and nice, and I won't be selfish if you'd not look away from me and forget me any more. If I'd your mother I'd be good perhaps, but I really think my mother doesn't understand boys." And he sighed deeply, and put his hands into his knickerbocker pockets.

"You'll not forget, and tease us again?" I asked firmly; "and you know I must ask Mother too."

"I'll promise, really," said Tommy, giving me a very grubby little hand; "only please do look at me as you look at Charley, and don't leave me all to myself again. I do get so tired of myself, you can't think."

I could, for once I had been left alone just in the same way; but I didn't tell Tommy this, and only went to Mother, and soon he was playing quite happily with us, and remained such a good boy. Nurse used to look out for spots on his chest every day when she bathed him, for she was quite sure that he must be going to be ill, but he wasn't; and he remained so good we were quite sorry to part with him, for he was really funny, and full of life. But as his mother kept very weak, Tommy was sent to school; and so, when we went back from the seaside, after the holidays were over, we did not meet again for nearly a year.

When we did meet, we hardly knew him again, he was such a jolly little fellow. And when he grew confidential, which he did the third day of the holidays, he said to me very solemnly, "I say, Hilda, if any little boys and girls are as rude and naughty as I used to be once, I know how to cure them. I shall first talk to them nicely, as your mother talked to me, and then I shall let them alone. It cured me, I know. You don't ever call me Tommy Torment now, do you, Hilda?"

THE TRICYCLE.

My grandfather does give me nice things! Last birthday he gave me a lovely box of tools, and he gave me the rocking-horse when I was quite little, and the swing trapeze that hangs from the nursery ceiling, and books and toys,—I can't remember them all now. But his last present was best of all: it was a tricycle!

I was nine last birthday, and I couldn't help wondering—though it sounds rather greedy—what grandfather would give me, because I thought it wouldn't be a toy, and he had given me a book at Christmas, for he said I was growing "quite a man."

When the birthday morning came, and I ran down to breakfast, there was nothing at all from grandfather! I'm afraid I looked very disappointed just at first; but presently we heard a little noise outside, and there was grandfather himself, and a man with him, who was wheeling the dearest little tricycle you ever saw.

It was rather hard work at first, and I soon got tired; but now I can go ten miles with father, and not feel at all tired.

I'll tell you one thing that makes me so glad about my tricycle. I was just going out on it one morning, when mother came running out of the house, looking so pale and frightened that I was quite frightened too.

"Bertie," she said, "tell John to go at once to Dr. Bell's and ask him to come here at once—at once, remember. Your father has cut his hand very badly, and we can't stop the bleeding."

"I'll go, mother; let me go on the tricycle," I said.

And she answered, "Do, dear; only make haste!"

I don't think I ever went so fast before; but it was a good road, and that helped me, and I was saying to myself all the time, "Oh, don't let me be too late for the doctor! Please let me find him and bring him to father."

And I did find the doctor at home. I was out of breath, but I managed to tell him what was the matter, and he was soon ready.

Of course I couldn't keep up with his pony-cart, as father could have done, but I got home not long after, and heard that the doctor was there, and the bleeding had stopped.

Father was very weak for some time, and his hand was not well for several weeks, but the doctor and mother said he would have died if I hadn't been able to fetch the doctor so quickly on my tricycle.

That's why I like my tricycle so much, and think it such a useful thing. If it had been a pony, it would have had to be saddled and bridled; but I always keep it cleaned and oiled, so it was quite ready for use when it was wanted. Mother used to be rather afraid of my riding it at one time, but she doesn't mind it now, because she knows how useful it was the day father cut his hand.

|

On the Threshold I. Bring me my grandson, Agnes, II. Do you think he is old enough yet, girl, III. You who are yet but a child, dear, IV. Old winter waits for the snowdrop V. We meet in the same wide doorway, F. W. H. |

TROT, TODDLES, AND THE TEA-PARTY.

Trot walked slowly up-stairs, repeating the words she had heard,—

"If you want the entertainment to be a success, you must draw up a programme, and carry it out."

She looked very solemn, for she felt the importance of the occasion. On the day following she and Toddles were to give their very first party; and four little girls and four little boys, not to mention the four dolls of the four little girls, were coming to take tea with Trot and Toddles and mother.

Trot had thought about it a great deal, and so had Toddles, wondering what would happen, and what they should do to make the guests enjoy themselves.

"TODDLES STOOD IN FRONT OF HER."

The two children had spent many half-hours talking the matter over, and each time the conversation had ended by Toddles saying,—"Well, never mind; there'll be tea." He had found out from cook that there would be two kinds of jam provided for the tea-party, and he felt quite sure that even if there were fourteen little boys and fourteen little girls expected, they would enjoy themselves thoroughly if they had plenty of jam. But Trot did not agree with him, and declared that the question could not be settled that way.

"'HIGHER!' SHOUTED TODDLES."

The speech which Trot had overheard suggested all kinds of plans, and she made her way into the nursery to talk over the party once more with Toddles.

Toddles was in the middle of a grand sea-fight. His tin soldiers were sailing about on books on the sea of the nursery floor, and Toddles was firing first at one ship, and then at another, with a large glass marble. Toddles did not wish to be disturbed.

"Toddles," said Trot, "the tea-party is settled at last. If you want the entertainment to be a success, you must draw up a programme, and carry it out."

"Six down at one shot!" cried Toddles; "and the captain among them, too."

"Toddles," said Trot solemnly, "you do want the entertainment to be a success, don't you?"

"TODDLES FELL DOWN."

Bang! bang! "There'll be tea," cried Toddles.

Trot touched him on the shoulder.

"Do come and talk about the party, Toddles," she said. "I have thought of a new game to play at."

Toddles looked up at last; he was beginning to feel interested. Trot's new games always meant fun, though they sometimes ended in a scolding from nurse.

"What is it?" he asked.

"A circus," answered Trot, with a smile.

"No," said Toddles, jumping up from the floor. "Do you really mean it?"

Trot sat down in a chair, and Toddles stood in front of her, and rested his two chubby elbows in her lap.

"TROT PUT THE JAR UPON HER HEAD."

"We must draw up a programme, and carry it out," said Trot, waving one arm, as she had seen her father do, when he had made the same remark down-stairs.

Toddles stared; he felt very much impressed, though he did not know in the least what Trot meant.

"And the circus will be the programme," continued Trot, drawing a dirty, crumpled piece of paper out of her pocket. "I will write it down on this. They will come at four o'clock."

"Oh, they'll come before that," objected Toddles. "You put 'Tea at 4' on the letters, and they are sure to come in plenty of time for tea. I should, because of the two kinds of jam, you know."

"Never mind," said Trot; "we can't do anything before tea, so the first thing to put down is 4 Tea;" and she wrote the word in big printing letters.

Toddles watched her silently.

"After tea will come the circus," said Trot. "I wonder how you spell circus?"

"But will mother let us have the circus?" said Toddles. "There won't be room in here for all the horses and clowns, and ladies we saw the other day."

"THERE WAS ... A SMASH"

Trot laughed. "That isn't the kind of circus I mean," she said; "we're to be the circus!"

Toddles looked more astonished than ever.

"We shall ask the party to sit in a circle," said Trot; "and then we shall do things. Perhaps we may as well settle now what to do."

"We must jump through hoops, of course," said Toddles.

"And walk about with things on our heads," said Trot; "balancing, they call it."

"I do wish we could walk on a rope like the man did the other day," said Toddles.

"We will," said Trot, writing busily.

The spelling was rather a trouble to her; but Toddles quite approved of it, and both children were satisfied with the programme when it was finished, though perhaps any one else might have found difficulty in understanding it. It looked something like this:

"4 TEA AFTER TEA JUMPING THREW HOOPS BALLUNCING TITE ROPES."

"Won't they be surprised?" said Toddles.

"Now we will practise," said Trot. "As we can't have any horses, I will hold the hoop, and you shall jump through it."

"That is much too easy," said Toddles. "Couldn't you stand on a chair, and let me jump off another chair through the hoop?"

Trot looked doubtful—"Nurse doesn't like us to stand on the chairs," she said.

|

A Silent Friend I who live in a house with a roof, F. W. Home. |

She fetched her big wooden hoop and held it up.

"Higher!" shouted Toddles, getting ready to make a spring.

Trot raised the hoop and Toddles jumped; then somehow Toddles and the hoop got mixed up together, and Toddles fell down on the ground.

"Oh dear!" said Trot. "I am sorry; we must try again."

Toddles picked himself up, and rubbed his elbows.

"Don't you think it will look stupid to jump through hoops when we can't ride on horses?" he said. "Of course if we had horses it would be easy enough. I think we had better leave that part out."

"'LET US TRY WALKING THE ROPE.'"

"Perhaps we had," said Trot; and she slowly drew her pencil through "JUMPING THREW HOOPS."

"We can both balance things," said Toddles, "I know;" and he jumped up quickly and ran across the room. "I will lie on my back, and put the footstool on my feet—"

"And throw it up in the air, and catch it," cried Trot. "Like the man with the tub the other day. That will be fine!—What shall I do?"

"Walk about with that pot on your head," suggested Toddles.

"That old thing," said Trot; "that will be very easy."

Toddles lay down on his back, and stuck the footstool on his feet, and Trot put the jar upon her head.

"It is quite easy," said Toddles, "and I am sure the party will like it."

"Quite easy," said Trot.

There was a sound of something falling, a cry, a little scream, and a smash.

"Oh!" cried Toddles.

"E—ee—eh!" cried Trot.

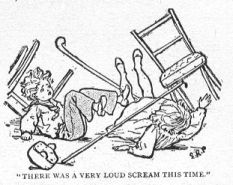

"THERE WAS A VERY LOUD SCREAM THIS TIME."

"It came right on my nose," said Toddles. "I believe it's broken."

"I'm sure my toe is," said Trot.

There was no doubt at all about the pot, it was very much broken.

"Hush!" said Trot, "there's nurse!"

Toddles stopped in the middle of a scream, and the two children crept on their hands and knees to the door, and listened eagerly—but it was a false alarm.

"Let us try walking the rope," said Trot.

"I suppose you will do that," said Toddles, rubbing his nose; "though we haven't any rope."

"Then we must find something else," said Trot cheerfully, determined not to be beaten. "I think a walking-stick would do beautifully to practise on, and we'll get nurse to give us a rope to-morrow."

"It looked very easy the other day," said Toddles, as Trot began to arrange one end of the stick on a chair, and the other on a stool; "but I don't expect it is."

"We'll be more careful this time," said Trot. "You hold the walking-stick so that it sha'n't slip, and I'll hold this long stick so that I sha'n't slip."

"All right," said Toddles, in a tone of voice which meant that he thought it was all wrong.

There was a loud scream this time—a scream that brought nurse up-stairs very quickly, so that she might see what was the matter.

Both the children were on the floor, and sticks, chair, and stool were flying in every direction.

For a minute nurse was doubtful which was Trot, which was Toddles, and which were sticks and chair.

"What are you doing?" said nurse.

But neither of the children answered. Toddles's head felt as if it had suddenly become twice its usual size, and Trot did not feel quite sure where she was, or whether she was standing on her head or her heels.

"TODDLES AND TROT WERE SITTING SIDE BY SIDE."

Nurse picked them up, and kissed them and comforted them, but quite forgot to scold the two miserable little pickles.

They didn't say anything about the circus, and somehow or other Toddles thought he would like to go to bed early; and of course there was no use in Trot staying up by herself, so she went to bed early too.

Next morning the children slept late, and did not seem very eager to get up when they did wake.

"Trot," said Toddles, sighing deeply, "it is the party day. What shall we do about the circus?"

Trot only answered with something between a groan and a growl.

"Children," said mother, coming into the nursery after breakfast, "shall we write to the boys and girls, and tell them to come another day?"

And though you will probably be astonished to hear it, Toddles and Trot nodded their heads and smiled.

"You wouldn't like it not to be a success," said mother.

"Trot," said Toddles, when mother had left the room, "you won't write a programme next time."

"If I do, Toddles," said Trot, "you may carry it out—out of the room, I mean."

But after all there was one part of the programme carried out.

At four o'clock that same afternoon Toddles and Trot were sitting side by side on the nursery floor, looking and feeling very unhappy and miserable.

"If only we hadn't hurt ourselves," said Trot, "we might have been having the party now."

"And the two kinds of jam," said Toddles. "Oh dear! oh dear!"

"Oh dear! oh dear!" said Trot.

The door opened, and nurse came into the room.

"Miss Trot, Master Toddles," said she, "you are to have tea down-stairs with mistress to-day."

Toddles and Trot looked surprised; but they jumped up quickly from the floor, forgetting for the moment all their aches and pains.

"Do you think," whispered Toddles to Trot, as they walked slowly down-stairs, "that there will be two kinds?"

Trot nodded her head. "I hope so," she said.

And there were.

|

BUTTERCUP LAND. They sailed away in a paper boat, E. Oxenford. |

"TEASING NED."

Such a terrible tease was Ned! Mother's patience lasted longer than any one else's, but even she was perhaps not altogether sorry when holidays were over and the boys were safely back at boarding-school. He teased the cats and the dogs and the chickens, teased the servants terribly with his mess and pranks; teased his bigger brother George, and more than all teased his good little sister Lizzie. "Lizababuff," she called herself, which was as near as her wee mouth could get to Elizabeth. George was something of a tease too, if the truth must be owned, only, beside Ned, people didn't notice him so much. Yet tease as they might, by hanging her dolls high out of reach in the walnut-tree, setting her dear black kitty afloat on the pond in a box, or laughing at her when she failed to catch little birds by putting salt on their tails, or any other way, and they had a great many, Lizzie never sulked; she forgave them directly, and wherever the boys played, in garden, orchard, or paddock, Lizzie's little fat face and white sun-bonnet could always be seen close by.

A very favorite place with the children was the paddock gate; here they would often swing for hours or amuse themselves by watching anything that might come along the road. Not much traffic passed that way, to be sure, but knowing every one in the village, they seemed to find enough to interest them.

"Here comes Tom Crippy with two baskets," cried Ned, as they all leaned over the gate one sunny afternoon,—an afternoon on which even Lizzie's sunny temper had almost given way, for both boys were in an especially teasing mood, and had brought tears very near her blue eyes more than once. "Don't they look heavy?" he went on. "My! He's got carrots and ripe apples in one. All ours are as hard as wood."

"Going to take them up to the house, Tom?"

"Not to yours, Master Ned," Tom answered, setting down his baskets and resting on a low wall. "This one is for you; but this one, with the apples, is for Mrs. Veale."

George looked at the baskets. "It is very hot, and you look tired right out," he said. "Suppose you leave Mrs. Veale's basket here while you take ours."

Tom Crippy agreed at once, and gladly made his way up to the house with his lightened load, Ned shouting after him, "I say, Tom, you may as well spare us an apple when you come back!"

"Wouldn't it be fun to hide his basket?" Ned went on; but, having offered to take care of it, both boys dismissed the idea as mean.

"Now for the apple," they said, when he returned.

In vain Tom protested, "I never promised it. It isn't mine to give! not even father's! Mrs. Veale has bought and paid for these apples."

George would have let him go after a bit; but Ned was somewhat greedy, and hankered after the apple, as well as after what he called a bit of fun.

"Well, it won't be more than a mouthful apiece," said Tom, at last. "Who'll have first bite?" and he took a ripe, red apple from the basket.

"I," cried Ned at once.

"Well!" said Tom, "I should have thought you would have let the little lady!"

He looked at George, who at once blinded Ned's eyes. Widely, eagerly, he opened his mouth, to close his teeth upon—a carrot.

People who tease can rarely stand being teased themselves. Frantic with rage, Ned struck out right and left, then dashing the basket over, trampled and smashed the delicious apples with his feet.

Well, the apples had to be paid for, and the boys had to be punished; even mother couldn't overlook such an afternoon's work as this.

The boys' pocket-money would be stopped till the two shillings were made up. Threepence a week each, and a month seemed long to look forward to. Gloomily they leaned over the gate in the evening. Patter, patter, nearer and nearer came little feet. "Lizababuff has opened her money-box, and here is sixpence for George and sixpence for Ned."

How they hugged the sun-bonnet! "Lizzie, you are a brick! But we won't take your money, nor tease you any more!"

"DAISY."

Far in the Highlands of Scotland, nestling amid their rugged mountains lay a beautiful farm. Here one of our boys lived with the good old farmer for two or three years, to be taught sheep-farming. Every summer he came to see us; and one year, as we were staying at a country house, he brought us a dear little pet lamb, which he had carried on his shoulder for many a mile across the country. It was a poor little orphan, its mother having died; but Willie had brought her up on warm new milk, which the farmer had given him. We at once named her Daisy, she was so white and fluffy, just like a snowball; and twice a day we used to feed her with warm milk out of a bottle. She very quickly got tame, roaming about and following us in our walks. She knew Sunday quite well, and never attempted to go to church with us but once; when we were half way there who should come panting after us but Daisy, so she had to be taken home, and very sulkily lay down beside Hero, the watch-dog, perhaps for a little sympathy. Of course she grew into a very big lamb, and as we had to go back to town for the winter a farmer offered to take Daisy and put her amongst his own flock of sheep. Next summer when we returned the first thing we did was to go and see Daisy. The flock was feeding in a meadow, and as we opened the gate a sheep darted from among them, came straight to us, and bleating out her welcome, trotted home with us. She went back to live with the farmer, and died at a good old age.

CHARLIE'S WORD.

"Well, children, I'll let you go and have this picnic by yourselves if you'll give me your word that you'll behave just as you would do if I were with you. Will you promise?"

"Yes, Nurse, we do promise; and we'll keep our word," said Algy Parker, "won't we?" and he turned round to Charlie, Basil, and little Ivy, as if to ask them to confirm his words.

"Yes, we promise," they repeated eagerly, full of delight to think that they might actually picnic by themselves for a whole day.

"Don't leave the Home Fields, mind," said Nurse. "You can't come to much harm there, I should think; and I should be glad of a free day, so as to get the nurseries cleaned out before your mother comes to-morrow; so mind your promise, and take good care of little Miss Ivy."

In a very short time all was ready. Cook had packed a most tempting lunch of ham sandwiches, plum-cake, and gooseberry turnovers, and this was placed in a basket on Algy's mail-cart; and then off he started, and Charlie and Basil, with little Ivy between them, ran after him down the long avenue, laughing and singing as joyfully as young birds.

The Home Fields lay at the bottom of the avenue, and the children were no sooner in them than Ivy gave a scream of delight. "The roses, Algy! The wild roses are out; oh, do pick me some!"

Ivy always got her own way with her brothers; and Algy obediently stopped, threw off his hat, pulled out his clasp-knife, and gathered a good bunch of the delicate blossoms for the little queen.

Charlie did not care for roses; he was better amused with the duck-pond, and began building a little pier for himself with some stones that lay near, much to the disgust of a pair of respectable old ducks, who considered the pond their private property, and very much resented Charlie's operations.

"Just listen to old Mrs. Quack preaching to me," cried Charlie, smiling to himself as he stood some little way in the pond. As he spoke, however, one of the stones of the pier slipped, and Charlie stumbled right into the water!

What of that?—it is a fine sunny day, and his boots will soon dry again, and he will not be a jot the worse.

Yes, quite true; but Nurse strictly forbade wet boots, and Charlie well knew that had she been there he would at once be sent back to the house to change them, and might think himself lucky if he escaped being put to bed as a punishment. Such things had happened before now in the Parker nursery; and Charlie recollected also there was no mother at home to-day to beg him off, as she often had done. But for all that Charlie's mind was made up; he had given his word to behave as if Nurse were by, and so he must go home.

"Perhaps she'll put you to bed," sobbed little Ivy.

"I can't help it," said Charlie sorrowfully. "I must keep my word."

So the poor boy trudged manfully back to the house to find his worst fears realized. Nurse was very busy and consequently cross; and on hearing Charlie's tale and seeing his boots, she sent him off to bed. "He'd be dry enough there," she averred.

Charlie knew there was no help for it, Nurse would be obeyed; so slowly and sorrowfully he began undressing, the large tears rolling down his cheeks, when the door opened and Mother stood there! She had come back sooner than was expected; and before Charlie quite realized all that was happening, Nurse had buttoned on his dry boots, and Mother and he were walking quickly towards the Home Fields. How the children did scream with delight when they found that Mother herself was going to picnic with them.

"You must thank Charlie that I am here," said Mother. "If he had not kept his promise to Nurse I should not have known where to find you;" and Mother looked fondly at her honest little boy.

"You see, I was obliged to," said Charlie simply: "I had given my word."

INDUSTRIOUS JACK.

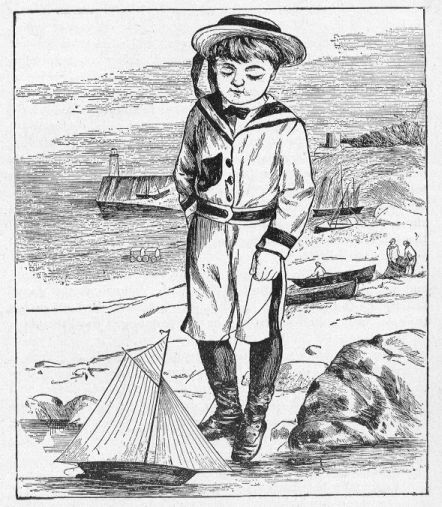

Jack, the lock-keeper's son, does not idle away his time after his day's work is done. He is very fond of boat-making; and although he has only some rough pieces of wood and an old pocket-knife, he is quite clever in constructing tiny vessels. Perhaps, some day, he may become a master boat-builder. Perseverance and the wise employment of spare moments will work wonders.

A VISIT TO NURSE.

It was indeed a treat for the four little Deverils when they received an invitation from old Nurse to spend the day at her cottage. She had lately married a gardener, and having no children of her own, she knew no greater pleasure than to entertain the little charges she had once nursed so faithfully. She always invited the children when the gooseberries were ripe, and each child had a special bush reserved for it by name; indeed, Nurse would have considered it "robbing the innocent" had any one else gathered so much as one berry off those bushes.

When they were tired of gooseberries, there was the swing under the apple-tree, and such a tea before they went home! The more buttered toast the children ate the better pleased was Nurse; and she brought plateful after plateful to the table, till even Sydney's appetite was appeased, and he felt the time had come for a little conversation.

"I'm going to be a sailor when I grow up, Nurse," he observed, "and I'll take you a-sail in my ship. Gerry says he'll be a schoolmaster; he wants to cane the boys, you know. Cyril has decided to be an omnibus conductor, and Baby," he concluded, pointing his finger at the only girl in the family, with a half-loving, half-contemptuous glance, "what do you think Baby says she'll do?"

Baby was just about to take a substantial bite out of her round of toast; but at Sydney's words she stopped halfway and said promptly, "Baby's going to take care of the poor soldiers."

Gerry, at the other end of the table, put down his mug with a satisfied gasp, and then burst out laughing, whilst Cyril raised his head and said solemnly, "The soldiers might shoot you, Baby."

Baby went on unconcernedly with her tea; and Sydney said loftily, "It's all nonsense, of course! She'll know better by and by. Children can't take care of soldiers, can they, Nurse?"

"Bless her heart!" said Nurse, as she softly stroked the fair little head, and placed a fresh plate of toast on the table.

"But can they, now?" persisted Sydney.