« back

OUR BOYS

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON, MARY E. WILKINS,

FRANCES A. HUMPHREY, MARGARET EYTINGE,

MRS. A. D. T. WHITNEY, MARY D. BRINE, Etc., Etc., Etc.

Profusely Illustrated.

AKRON, OHIO

1904

The Cat-tail Arrow

BY CLARA DOTY BATES

![[Illuminated letter] L](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/63.png)

Well indeed he loved to whittle,

Shaped it like the half of O—

How he could I scarcely know,

For his fingers were so little.

As he whittled came a sigh:

"If I only had an arrow;

Something light enough to fly

To the tree-tops or the sky!

Then I'd have such fun tomorrow."

Then he thought of all the slim

Things that grow—the hazel bushes,

Willow branches, poplars trim—

And yet nothing suited him

Till he chanced to think of rushes.

He knew well a quiet pool

Where he always paused a minute

On his way to district school,

Just to see the waters cool

And his own bright face within it.

There the cat-tails thickly grew,

With their heads so brown and furry;

They were straight and slender too,

Plenty strong enough he knew,

And he sought them in a hurry.

Such an arrow as he wrought—

Almost passed a boy's believing.

When he drew the bow-string taut,

Out of sight and quick as thought

Up it went, the blue air cleaving.

Who was Sammie, would you know?

It was grandpa—he was little

Nearly eighty years ago;

But 'tis no doubt as fine a bow

As the best he still could whittle.

A YOUNG SALT.

A YOUNG SALT.HE COULDN'T SAY NO.

![[Illuminated letter] I](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/62.png)

He just was full of knowledge,

His studies swept the whole broad range

Of High School and of College;

He read in Greek and Latin too,

Loud Sanscrit he could utter,

But one small thing he couldn't do

That comes as pat to me and you

As eating bread and butter:

He couldn't say "No!" He couldn't say "No!"

I'm sorry to say it was really so!

He'd diddle, and dawdle, and stutter, but oh!

When it came to the point he could never say "No!"

Geometry he knew by rote,

Like any Harvard Proctor;

He'd sing a fugue out, note by note;

Knew Physics like a Doctor;

He spoke in German and in French;

Knew each Botanic table;

But one small word that you'll agree

Comes pat enough to you and me,

To speak he was not able:

For he couldn't say "No!" He couldn't say "No!"

'Tis dreadful, of course, but 'twas really so.

He'd diddle, and dawdle, and stutter, but oh!

When it came to the point he could never say "No!"

And he could fence, and swim, and float,

And use the gloves with ease too,

Could play base ball, and row a boat,

And hang on a trapeze too;

His temper was beyond rebuke,

And nothing made him lose it;

His strength was something quite superb,

But what's the use of having nerve

If one can never use it?

He couldn't say "No!" He couldn't say "No!"

If one asked him to come, if one asked him to go,

He'd diddle, and dawdle, and stutter, but oh!

When it came to the point he could never say "No!"

When he was but a little lad,

In life's small ways progressing,

He fell into this habit bad

Of always acquiescing;

'Twas such an amiable trait,

To friend as well as stranger,

That half unconsciously at last

The custom held him hard and fast

Before he knew the danger,

And he couldn't say "No!" He couldn't say "No!"

To his prospects you see 'twas a terrible blow.

He'd diddle, and dawdle, and stutter, but oh!

When it came to the point he could never say "No!"

And so for all his weary days

The best of chances failed him;

He lived in strange and troublous ways

And never knew what ailed him;

He'd go to skate when ice was thin;

He'd join in deeds unlawful,

He'd lend his name to worthless notes,

He'd speculate in stocks and oats;

'Twas positively awful,

For he couldn't say "No!" He couldn't say "No!"

He would veer like a weather-cock turning so slow;

He'd diddle, and dawdle, and stutter, but oh!

When it came to the point he could never say "No!"

Then boys and girls who hear my song,

Pray heed its theme alarming:

Be good, be wise, be kind, be strong—

These traits are always charming,

But all your learning, all your skill

With well-trained brain and muscle,

Might just as well be left alone,

If you can't cultivate backbone

To help you in life's tussle,

And learn to say "No!" Yes, learn to say "No!"

Or you'll fall from the heights to the rapids below!

You may waver, and falter, and tremble, but oh!

When your conscience requires it, be sure and shout "No!"

THE CHRISTMAS MONKS.

![[Illuminated letter] A](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/58.png)

The Convent of the Christmas Monks is a most charmingly picturesque pile of old buildings; there are towers and turrets, and peaked roofs and arches, and everything which could possibly be thought of in the architectural line, to make a convent picturesque. It is built of graystone; but it is only once in a while that you can see the graystone, for the walls are almost completely covered with mistletoe and ivy and evergreen. There are the most delicious little arched windows with diamond panes peeping out from the mistletoe and evergreen, and always at all times of the year, a little Christmas wreath of ivy and holly-berries is suspended in the centre of every window. Over all the doors, which are likewise arched, are Christmas garlands, and over the main entrance Merry Christmas in evergreen letters.

The Christmas Monks are a jolly brethren; the robes of their order are white, gilded with green garlands, and they never are seen out at any time of the year without Christmas wreaths on their heads. Every morning they file in a long procession into the chapel to sing a Christmas carol; and every evening they ring a Christmas chime on the convent bells. They eat roast turkey and plum pudding and mince-pie for dinner all the year round; and always carry what is left in baskets trimmed with evergreen to the poor people. There are always wax candles lighted and set in every window of the convent at nightfall; and when the people in the country about get uncommonly blue and down-hearted, they always go for a cure to look at the Convent of the Christmas Monks after the candles are lighted and the chimes are ringing. It brings to mind things which never fail to cheer them.

But the principal thing about the Convent of the Christmas Monks is the garden; for that is where the Christmas presents grow. This garden extends over a large number of acres, and is divided into different departments, just as we divide our flower and vegetable gardens; one bed for onions, one for cabbages, and one for phlox, and one for verbenas, etc.

Every spring the Christmas Monks go out to sow the Christmas-present seeds after they have ploughed the ground and made it all ready.

There is one enormous bed devoted to rocking-horses. The rocking-horse seed is curious enough; just little bits of rocking-horses so small that they can only be seen through a very, very powerful microscope. The Monks drop these at quite a distance from each other, so that they will not interfere while growing; then they cover them up neatly with earth, and put up a sign-post with "Rocking-horses" on it in evergreen letters. Just so with the penny-trumpet seed, and the toy-furniture seed, the skate-seed, the sled-seed, and all the others.

Perhaps the prettiest, and most interesting part of the garden, is that devoted to wax dolls. There are other beds for the commoner dolls—for the rag dolls, and the china dolls, and the rubber dolls, but of course wax dolls would look much handsomer growing. Wax dolls have to be planted quite early in the season; for they need a good start before the sun is very high. The seeds are the loveliest bits of microscopic dolls imaginable. The Monks sow them pretty close together, and they begin to come up by the middle of May. There is first just a little glimmer of gold, or flaxen, or black, or brown, as the case may be, above the soil. Then the snowy foreheads appear, and the blue eyes, and the black eyes, and, later on, all those enchanting little heads are out of the ground, and are nodding and winking and smiling to each other the whole extent of the field; with their pinky cheeks and sparkling eyes and curly hair there is nothing so pretty as these little wax doll heads peeping out of the earth. Gradually, more and more of them come to light, and finally by Christmas they are all ready to gather. There they stand, swaying to and fro, and dancing lightly on their slender feet which are connected with the ground, each by a tiny green stem; their dresses of pink, or blue, or white—for their dresses grow with them—flutter in the air. Just about the prettiest sight in the world is the bed of wax dolls in the garden of the Christmas Monks at Christmas time. Of course ever since this convent and garden were established (and that was so long ago that the wisest man can find no books about it) their glories have attracted a vast deal of admiration and curiosity from the young people in the surrounding country; but as the garden is enclosed on all sides by an immensely thick and high hedge, which no boy could climb, or peep over, they could only judge of the garden by the fruits which were parceled out to them on Christmas-day.

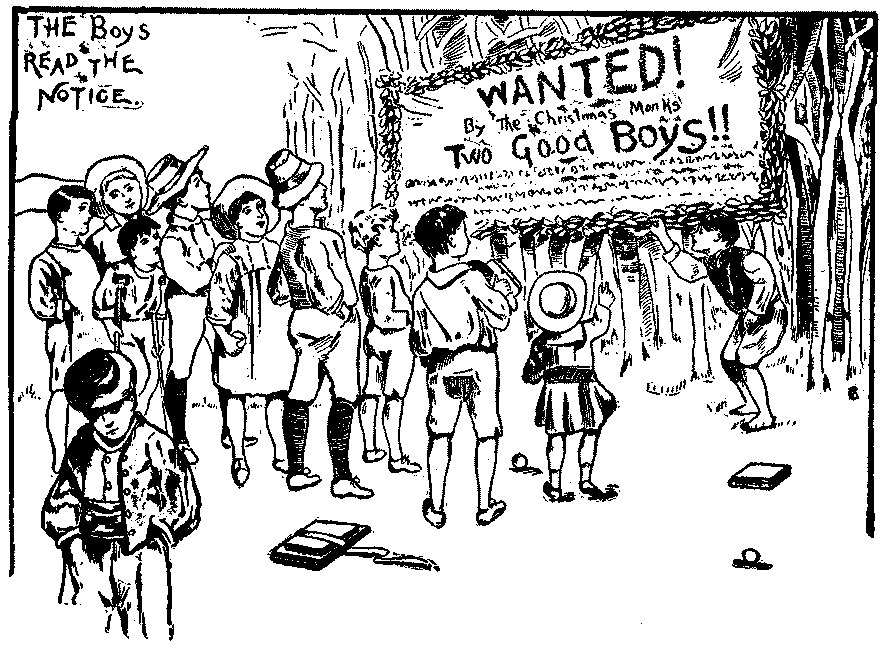

You can judge, then, of the sensation among the young folks, and older ones, for that matter, when one evening there appeared hung upon a conspicuous place in the garden-hedge, a broad strip of white cloth trimmed with evergreen and printed with the following notice in evergreen letters:

"Wanted—By the Christmas Monks, two good boys to assist in garden work. Applicants will be examined by Fathers Anselmus and Ambrose, in the convent refectory, on April 10th."

This notice was hung out about five o'clock in the evening, some time in the early part of February. By noon the street was so full of boys staring at it with their mouths wide open, so as to see better, that the king was obliged to send his bodyguard before him to clear the way with brooms, when he wanted to pass on his way from his chamber of state to his palace.

There was not a boy in the country but looked upon this position as the height of human felicity. To work all the year in that wonderful garden, and see those wonderful things growing! and without doubt any body who worked there could have all the toys he wanted, just as a boy who works in a candy-shop always has all the candy he wants!

But the great difficulty, of course, was about the degree of goodness requisite to pass the examination. The boys in this country were no worse than the boys in other countries, but there were not many of them that would not have done a little differently if he had only known beforehand of the advertisement of the Christmas Monks. However, they made the most of the time remaining, and were so good all over the kingdom that a very millennium seemed dawning. The school teachers used their ferrules for fire wood, and the king ordered all the birch trees cut down and exported, as he thought there would be no more call for them in his own realm.

When the time for the examination drew near, there were two boys whom every one thought would obtain the situation, although some of the other boys had lingering hopes for themselves; if only the Monks would examine them on the last six weeks, they thought they might pass. Still all the older people had decided in their minds that the Monks would choose these two boys. One was the Prince, the king's oldest son; and the other was a poor boy named Peter. The Prince was no better than the other boys; indeed, to tell the truth, he was not so good; in fact, was the biggest rogue in the whole country; but all the lords and the ladies, and all the people who admired the lords and ladies, said it was their solemn belief that the Prince was the best boy in the whole kingdom; and they were prepared to give in their testimony, one and all, to that effect to the Christmas Monks.

Peter was really and truly such a good boy that there was no excuse for saying he was not. His father and mother were poor people; and Peter worked every minute out of school hours to help them along. Then he had a sweet little crippled sister whom he was never tired of caring for. Then, too, he contrived to find time to do lots of little kindnesses for other people. He always studied his lessons faithfully, and never ran away from school. Peter was such a good boy, and so modest and unsuspicious that he was good, that everybody loved him. He had not the least idea that he could get the place with the Christmas Monks, but the Prince was sure of it.

When the examination day came all the boys from far and near, with their hair neatly brushed and parted, and dressed in their best clothes, flocked into the convent. Many of their relatives and friends went with them to witness the examination.

The refectory of the convent, where they assembled, was a very large hall with a delicious smell of roast turkey and plum pudding in it. All the little boys sniffed, and their mouths watered.

The two fathers who were to examine the boys were perched up in a high pulpit so profusely trimmed with evergreen that it looked like a bird's nest; they were remarkably pleasant-looking men, and their eyes twinkled merrily under their Christmas wreaths. Father Anselmus was a little the taller of the two, and Father Ambrose was a little the broader; and that was about all the difference between them in looks.

The little boys all stood up in a row, their friends stationed themselves in good places, and the examination began.

Then if one had been placed beside the entrance to the convent, he would have seen one after another, a crestfallen little boy with his arm lifted up and crooked, and his face hidden in it, come out and walk forlornly away. He had failed to pass.

The two fathers found out that this boy had robbed birds' nests, and this one stolen apples. And one after another they walked disconsolately away till there were only two boys left: the Prince and Peter.

"Now, your Highness," said Father Anselmus, who always took the lead in the questions, "are you a good boy?"

"O holy Father!" exclaimed all the people—there were a good many fine folks from the court present. "He is such a good boy! such a wonderful boy! We never knew him to do a wrong thing in his sweet life."

"I don't suppose he ever robbed a bird's nest?" said Father Ambrose a little doubtfully.

"No, no!" chorused the people.

"Nor tormented a kitten?"

"No, no, no!" cried they all.

At last everybody being so confident that here could be no reasonable fault found with the Prince, he was pronounced competent to enter upon the Monks' service. Peter they knew a great deal about before—indeed, a glance at his face was enough to satisfy any one of his goodness; for he did look more like one of the boy angels in the altar-piece than anything else. So after a few questions, they accepted him also; and the people went home and left the two boys with the Christmas Monks.

The next morning Peter was obliged to lay aside his homespun coat, and the Prince his velvet tunic, and both were dressed in some little white robes with evergreen girdles like the Monks. Then the Prince was set to sowing Noah's ark seed, and Peter picture-book seed. Up and down they went scattering the seed. Peter sang a little psalm to himself, but the Prince grumbled because they had not given him gold-watch or gem seed to plant instead of the toy which he had outgrown long ago. By noon Peter had planted all his picture-books, and fastened up the card to mark them on the pole; but the Prince had dawdled so his work was not half done.

"We are going to have a trial with this boy," said the Monks to each other; "we shall have to set him a penance at once, or we cannot manage him at all."

So the Prince had to go without his dinner, and kneel on dried peas in the chapel all the afternoon. The next day he finished his Noah's Arks meekly; but the next day he rebelled again and had to go the whole length of the field where they planted jewsharps, on his knees. And so it was about every other day for the whole year.

One of the brothers had to be set apart in a meditating cell to invent new penances; for they had used up all on their list before the Prince had been with them three months.

The Prince became dreadfully tired of his convent life, and if he could have brought it about would have run away. Peter, on the contrary, had never been so happy in his life. He worked like a bee, and the pleasure he took in seeing the lovely things he had planted come up, was unbounded, and the Christmas carols and chimes delighted his soul. Then, too, he had never fared so well in his life. He could never remember the time before when he had been a whole week without being hungry. He sent his wages every month to his parents; and he never ceased to wonder at the discontent of the Prince.

"They grow so slow," the Prince would say, wrinkling up his handsome forehead. "I expected to have a bushelful of new toys every month; and not one have I had yet. And these stingy old Monks say I can only have my usual Christmas share anyway, nor can I pick them out myself. I never saw such a stupid place to stay in my life. I want to have my velvet tunic on and go home to the palace and ride on my white pony with the silver tail, and hear them all tell me how charming I am." Then the Prince would crook his arm and put his head on it and cry.

Peter pitied him, and tried to comfort him, but it was not of much use, for the Prince got angry because he was not discontented as well as himself.

Two weeks before Christmas everything in the garden was nearly ready to be picked. Some few things needed a little more December sun, but everything looked perfect. Some of the Jack-in-the-boxes would not pop out quite quick enough, and some of the jumping-Jacks were hardly as limber as they might be as yet; that was all. As it was so near Christmas the Monks were engaged in their holy exercises in the chapel for the greater part of the time, and only went over the garden once a day to see if everything was all right.

The Prince and Peter were obliged to be there all the time. There was plenty of work for them to do; for once in a while something would blow over, and then there were the penny-trumpets to keep in tune; and that was a vast sight of work.

One morning the Prince was at one end of the garden straightening up some wooden soldiers which had toppled over, and Peter was in the wax doll bed dusting the dolls. All of a sudden he heard a sweet little voice: "O, Peter!" He thought at first one of the dolls was talking, but they could not say anything but papa and mamma; and had the merest apologies for voices anyway. "Here I am, Peter!" and there was a little pull at his sleeve. There was his little sister. She was not any taller than the dolls around her, and looked uncommonly like the prettiest, pinkest-cheeked, yellowest-haired ones; so it was no wonder that Peter did not see her at first. She stood there poising herself on her crutches, poor little thing, and smiling lovingly up at Peter.

"Oh, you darling!" cried Peter, catching her up in his arms. "How did you get in here?"

"I stole in behind one of the Monks," said she. "I saw him going up the street past our house, and I ran out and kept behind him all the way. When he opened the gate I whisked in too, and then I followed him into the garden. I've been here with the dollies ever since."

"Well," said poor Peter, "I don't see what I am going to do with you, now you are here. I can't let you out again; and I don't know what the Monks will say."

"Oh, I know!" cried the little girl gayly. "I'll stay out here in the garden. I can sleep in one of those beautiful dolls' cradles over there; and you can bring me something to eat."

"But the Monks come out every morning to look over the garden, and they'll be sure to find you," said her brother, anxiously.

"No, I'll hide! O Peter, here is a place where there isn't any doll!"

"Yes; that doll did not come up."

"Well, I'll tell you what I'll do! I'll just stand here in this place where the doll didn't come up, and nobody can tell the difference."

"Well, I don't know but you can do that," said Peter, although he was still ill at ease. He was so good a boy he was very much afraid of doing wrong, and offending his kind friends the Monks; at the same time he could not help being glad to see his dear little sister.

He smuggled some food out to her, and she played merrily about him all day; and at night he tucked her into one of the dolls' cradles with lace pillows and quilt of rose-colored silk.

The next morning when the Monks were going the rounds, the father who inspected the wax doll bed was a bit nearsighted, and he never noticed the difference between the dolls and Peter's little sister, who swung herself on her crutches, and looked just as much like a wax doll as she possibly could. So the two were delighted with the success of their plan.

They went on thus for a few days, and Peter could not help being happy with his darling little sister, although at the same time he could not help worrying for fear he was doing wrong.

Something else happened now, which made him worry still more; the Prince ran away. He had been watching for a long time for an opportunity to possess himself of a certain long ladder made of twisted evergreen ropes, which the Monks kept locked up in the toolhouse. Lately, by some oversight, the toolhouse had been left unlocked one day, and the Prince got the ladder. It was the latter part of the afternoon, and the Christmas Monks were all in the chapel practicing Christmas carols. The Prince found a very large hamper, and picked as many Christmas presents for himself as he could stuff into it; then he put the ladder against the high gate in front of the convent, and climbed up, dragging the hamper after him. When he reached the top of the gate, which was quite broad, he sat down to rest for a moment before pulling the ladder up so as to drop it on the other side.

He gave his feet a little triumphant kick as he looked back at his prison, and down slid the evergreen ladder! The Prince lost his balance, and would inevitably have broken his neck if he had not clung desperately to the hamper which hung over on the convent side of the fence; and as it was just the same weight as the Prince, it kept him suspended on the other.

He screamed with all the force of his royal lungs; was heard by a party of noblemen who were galloping up the street; was rescued, and carried in state to the palace. But he was obliged to drop the hamper of presents, for with it all the ingenuity of the noblemen could not rescue him as speedily as it was necessary they should.

When the good Monks discovered the escape of the Prince they were greatly grieved, for they had tried their best to do well by him; and poor Peter could with difficulty be comforted. He had been very fond of the Prince, although the latter had done little except torment him for the whole year; but Peter had a way of being fond of folks.

A few days after the Prince ran away, and the day before the one on which the Christmas presents were to be gathered, the nearsighted father went out into the wax doll field again; but this time he had his spectacles on, and could see just as well as any one, and even a little better. Peter's little sister was swinging herself on her crutches, in the place where the wax doll did not come up, tipping her little face up, and smiling just like the dolls around her.

"Why, what is this!" said the father. "Hoc credam! I thought that wax doll did not come up. Can my eyes deceive me? non verum est! There is a doll there—and what a doll! on crutches, and in poor, homely gear!"

Then the nearsighted father put out his hand toward Peter's little sister. She jumped—she could not help it, and the holy father jumped too; the Christmas wreath actually tumbled off his head.

"It is a miracle!" exclaimed he when he could speak; "the little girl is alive! parra puella viva est. I will pick her and take her to the brethren, and we will pay her the honors she is entitled to."

Then the good father put on his Christmas wreath, for he dare not venture before his abbot without it, picked up Peter's little sister, who was trembling in all her little bones, and carried her into the chapel, where the Monks were just assembling to sing another carol. He went right up to the Christmas abbot, who was seated in a splendid chair, and looked like a king.

"Most holy abbot," said the nearsighted father, holding out Peter's little sister, "behold a miracle, vide miraculum! Thou wilt remember that there was one wax doll planted which did not come up. Behold, in her place I have found this doll on crutches, which is—alive!"

"Let me see her!" said the abbot; and all the other Monks crowded around, opening their mouths just like the little boys around the notice, in order to see better.

"Verum est," said the abbot. "It is verily a miracle."

"Rather a lame miracle," said the brother who had charge of the funny picture-books and the toy monkeys; they rather threw his mind off its level of sobriety, and he was apt to make frivolous speeches unbecoming a monk.

The abbot gave him a reproving glance, and the brother, who was the leach of the convent, came forward. "Let me look at the miracle, most holy abbot," said he. He took up Peter's sister, and looked carefully at the small, twisted ankle. "I think I can cure this with my herbs and simples," said he.

"But I don't know," said the abbot doubtfully. "I never heard of curing a miracle."

"If it is not lawful, my humble power will not suffice to cure it," said the father who was the leach.

"True," said the abbot; "take her, then, and exercise thy healing art upon her, and we will go on with our Christmas devotions, for which we should now feel all the more zeal."

So the father took away Peter's little sister, who was still too frightened to speak.

The Christmas Monk was a wonderful doctor, for by Christmas eve the little girl was completely cured of her lameness. This may seem incredible, but it was owing in great part to the herbs and simples, which are of a species that our doctors have no knowledge of; and also to a wonderful lotion which has never been advertised on our fences.

Peter of course heard the talk about the miracle, and knew at once what it meant. He was almost heartbroken to think he was deceiving the Monks so, but at the same time he did not dare to confess the truth for fear they would put a penance upon his sister, and he could not bear to think of her having to kneel upon dried peas.

He worked hard picking Christmas presents, and hid his unhappiness as best he could. On Christmas eve he was called into the chapel. The Christmas Monks were all assembled there. The walls were covered with green garlands and boughs and sprays of holly berries, and branches of wax lights Were gleaming brightly amongst them. The altar and the picture of the Blessed Child behind it were so bright as to almost dazzle one; and right up in the midst of it, in a lovely white dress, all wreaths and jewels, in a little chair with a canopy woven of green branches over it, sat Peter's little sister.

And there were all the Christmas Monks in their white robes and wreaths, going up in a long procession, with their hands full of the very showiest Christmas presents to offer them to her!

But when they reached her and held out the lovely presents—the first was an enchanting wax doll, the biggest beauty in the whole garden—instead of reaching out her hands for them, she just drew back, and said in her little sweet, piping voice: "Please, I ain't a millacle, I'm only Peter's little sister."

"Peter?" said the abbot; "the Peter who works in our garden?"

"Yes," said the little sister.

Now here was a fine opportunity for a whole convent full of monks to look foolish—filing up in procession with their hands full of gifts to offer to a miracle, and finding there was no miracle, but only Peter's little sister.

But the abbot of the Christmas Monks had always maintained that there were two ways of looking at all things; if any object was not what you wanted it to be in one light, that there was another light in which it would be sure to meet your views.

So now he brought this philosophy to bear.

"This little girl did not come up in the place of the wax doll, and she is not a miracle in that light," said he; "but look at her in another light and she is a miracle—do you not see?"

They all looked at her, the darling little girl, the very meaning and sweetness of all Christmas in her loving, trusting, innocent face.

"Yes," said all the Christmas Monks, "she is a miracle." And they all laid their beautiful Christmas presents down before her.

Peter was so delighted he hardly knew himself; and, oh! the joy there was when he led his little sister home on Christmas-day, and showed all the wonderful presents.

The Christmas Monks always retained Peter in their employ—in fact he is in their employ to this day. And his parents, and his little sister who was entirely cured of her lameness, have never wanted for anything.

As for the Prince, the courtiers were never tired of discussing and admiring his wonderful knowledge of physics which led to his adjusting the weight of the hamper of Christmas presents to his own so nicely that he could not fall. The Prince liked the talk and the admiration well enough, but he could not help, also, being a little glum; for he got no Christmas presents that year.

TEDDY AND THE ECHO.

![[Illuminated letter] T](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/67.png)

His oars a softened click-clack make;

On all that water bright and blue,

His boat is the only one in view;

So, when he hears another oar

Click-clack along the farthest shore,

"Heigh-ho," he cries, "out for a row!

Echo is out! heigh-ho—heigh-ho!"

"Heigh-ho, heigh-ho!"

Sounds from the distance, faint and low.

Then Teddy whistles that he may hear

Her answering whistle, soft and clear;

Out of the greenwood, leafy, mute,

Pipes her mimicking, silver flute,

And, though her mellow measures are

Always behind him half a bar,

'Tis sweet to hear her falter so;

And Ted calls back, "Bravo, bravo!"

"Bravo, bravo!"

Comes from the distance, faint and low.

She laughs at trifles loud and long;

Splashes the water, sings a song;

Tells him everything she is told,

Saucy or tender, rough or bold;

One might think from the merry noise

That the quiet wood was full of boys,

Till Ted, grown tired, cries out, "Oh, no!

'Tis dinner time and I must go!"

"Must go? must go?"

Sighs from the distance, sad and low.

When Ted and his clatter are away,

Where does the little Echo stay?

Perched on a rock to watch for him?

Or keeping a lookout from some limb?

If he were to push his boat to land,

Would he find her footprint on the sand?

Or would she come to his blithe "hello,"

Red as a rose, or white as snow?

Ah no, ah no!

Never can Teddy see Echo!

SONG OF THE CHRISTMAS STOCKINGS.

![[Illuminated letter] S](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/66.png)

Hanging by the chimney snug and tight:

Jolly, jolly red,

That belongs to Ted;

Daintiest blue,

That belongs to Sue;

Old brown fellow

Hanging long,

That belongs to Joe,

Big and strong;

Little, wee, pink mite

Covers Baby's toes—

Won't she pull it open

With funny little crows!

Sober, dark gray,

Quiet little mouse,

That belongs to Sybil

Of all the house;

One stocking left,

Whose should it be?

Why, that I'm sure

Must belong to me!

Well, so they hang, packed to the brim,

Swing, swing, swing, in the firelight dim.

'Twas the middle of the night.

Open flew my eyes;

I started up in bed,

And stared in surprise;

I rubbed my eyes, I rubbed my ears,

I saw the stockings swing, I heard the stockings sing;

Out in the firelight

Merry and bright,

Snug and tight,

Six were swinging,

Six were singing,

Like everything!

And the red, and the blue, and the brown, and the gray,

And the pink one, and mine, had it all their own way,

And no one could stop them—because, don't you see,

Nobody heard 'em—but just poor me!

"All day we carry toes,

To-night we carry candy;

Christmas comes once a year

Very nice and handy.

Run, run, race all day,

Mother mends us after play,

We don't care, life is gay,

Sing and swing, away, away!

"Boots and little tired shoes,

We kick 'em off in glee;

It's fun to hang up here

And Santa Claus to see.

Run, run, race all day,

Mother mends us after play,

We don't care, life is gay,

Sing and swing, away, away!

"To-morrow down we come,

The sweet things tumble out,

Then carrying toes again

We'll have to trot about.

Run, run, race all day,

Mother'll mend us after play,

We don't care, we'll swing so gay

While we can—away, away!"

JOE LAMBERT'S FERRY.

![[Illuminated letter] I](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/62.png)

It was about as disagreeable a morning for going out as can be imagined; and yet everybody in the little Western river town who could get out went out and stayed out.

Men and women, boys and girls, and even little children, ran to the river-bank: and, once there, they stayed, with no thought, it seemed, of going back to their homes or their work.

The people of the town were wild with excitement, and everybody told everybody else what had happened, although everybody knew all about it already. Everybody, I mean, except Joe Lambert, and he had been so busy ever since daylight, sawing wood in Squire Grisard's woodshed, that he had neither seen nor heard anything at all. Joe was the poorest person in the town. He was the only boy there who really had no home and nobody to care for him. Three or four years before this March morning, Joe had been left an orphan, and being utterly destitute, he should have been sent to the poorhouse, or "bound out" to some person as a sort of servant. But Joe Lambert had refused to go to the poorhouse or to become a bound boy. He had declared his ability to take care of himself, and by working hard at odd jobs, sawing wood, rolling barrels on the wharf, picking apples or weeding onions as opportunity offered, he had managed to support himself "after a manner," as the village people said. That is to say, he generally got enough to eat, and some clothes to wear. He slept in a warehouse shed, the owner having given him leave to do so on condition that he would act as a sort of watchman on the premises.

Joe Lambert alone of all the villagers knew nothing of what had happened; and of course Joe Lambert did not count for anything in the estimation of people who had houses to live in. The only reason I have gone out of the way to make an exception of so unimportant a person is, that I think Joe did count for something on that particular March day at least.

When he finished the pile of wood that he had to saw, and went to the house to get his money, he found nobody there. Going down the street he found the town empty, and, looking down a cross street, he saw the crowds that had gathered on the river-bank, thus learning at last that something unusual had occurred. Of course he ran to the river to learn what it was.

When he got there he learned that Noah Martin the fisherman who was also the ferryman between the village and its neighbor on the other side of the river, had been drowned during the early morning in a foolish attempt to row his ferry skiff across the stream. The ice which had blocked the river for two months, had begun to move on the day before, and Martin with his wife and baby—a child about a year old—were on the other side of the river at the time. Early on that morning there had been a temporary gorging of the ice about a mile above the town, and, taking advantage of the comparatively free channel, Martin had tried to cross with his wife and child, in his boat.

The gorge had broken up almost immediately, as the river was rising rapidly, and Martin's boat had been caught and crushed in the ice. Martin had been drowned, but his wife, with her child in her arms, had clung to the wreck of the skiff, and had been carried by the current to a little low-lying island just in front of the town.

What had happened was of less importance, however, than what people saw must happen. The poor woman and baby out there on the island, drenched as they had been in the icy water, must soon die with cold, and, moreover, the island was now nearly under water, while the great stream was rising rapidly. It was evident that within an hour or two the water would sweep over the whole surface of the island, and the great fields of ice would of course carry the woman and child to a terrible death.

Many wild suggestions were made for their rescue, but none that gave the least hope of success. It was simply impossible to launch a boat. The vast fields of ice, two or three feet in thickness, and from twenty feet to a hundred yards in breadth, were crushing and grinding down the river at the rate of four or five miles an hour, turning and twisting about, sometimes jamming their edges together with so great a force that one would lap over another, and sometimes drifting apart and leaving wide open spaces between for a moment or two. One might as well go upon such a river in an egg shell as in the stoutest row-boat ever built.

The poor woman with her babe could be seen from the shore, standing there alone on the rapidly narrowing strip of island. Her voice could not reach the people on the bank, but when she held her poor little baby toward them in mute appeal for help, the mothers there understood her agony.

There was nothing to be done, however. Human sympathy was given freely, but human help was out of the question. Everybody on the river-shore was agreed in that opinion. Everybody, that is to say, except Joe Lambert. He had been so long in the habit of finding ways to help himself under difficulties, that he did not easily make up his mind to think any case hopeless.

No sooner did Joe clearly understand how matters stood than he ran away from the crowd, nobody paying any attention to what he did. Half an hour later somebody cried out: "Look there! Who's that, and what's he going to do?" pointing up the stream.

Looking in that direction, the people saw some one three quarters of a mile away standing on a floating field of ice in the river. He had a large farm-basket strapped upon his shoulders, while in his hands he held a plank.

As the ice-field upon which he stood neared another, the youth ran forward, threw his plank down, making a bridge of it, and crossed to the farther field. Then picking up his plank, he waited for a chance to repeat the process.

As he thus drifted down the river, every eye was strained in his direction. Presently some one cried out: "It's Joe Lambert; and he's trying to cross to the island!"

There was a shout as the people understood the nature of Joe's heroic attempt, and then a hush as its extreme danger became apparent.

Joe had laid his plans wisely and well, but it seemed impossible that he could succeed. His purpose was, with the aid of the plank to cross from one ice-field to another until he should reach the island; but as that would require a good deal of time, and the ice was moving down stream pretty rapidly, it was necessary to start at a point above the town. Joe had gone about a mile up the river before going on the ice, and when first seen from the town he had already reached the channel.

After that first shout a whisper might have been heard in the crowd on the bank. The heroism of the poor boy's attempt awed the spectators, and the momentary expectation that he would disappear forever amid the crushing ice-fields, made them hold their breath in anxiety and terror.

His greatest danger was from the smaller cakes of ice. When it became necessary for him to step upon one of these, his weight was sufficient to make it tilt, and his footing was very insecure. After awhile as he was nearing the island, he came into a large collection of these smaller ice-cakes. For awhile he waited, hoping that a larger field would drift near him; but after a minute's delay he saw that he was rapidly floating past the island, and that he must either trust himself to the treacherous broken ice, or fail in his attempt to save the woman and child.

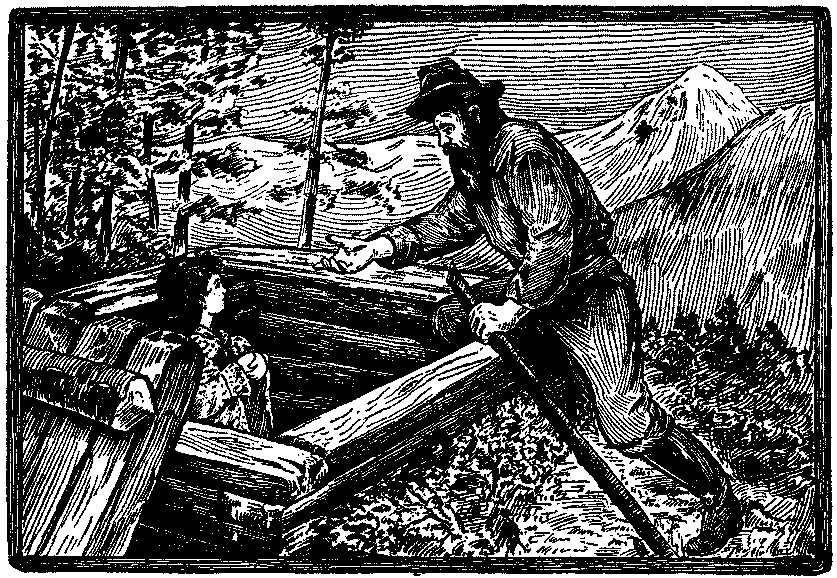

Joe Saves Mrs. Martin and Baby Martin.

Joe Saves Mrs. Martin and Baby Martin.Choosing the best of the floes, he laid his plank and passed across successfully. In the next passage, however, the cake tilted up, and Joe Lambert went down into the water! A shudder passed through the crowd on shore.

"Poor fellow!" exclaimed some tender-hearted spectator; "it is all over with him now."

"No; look, look!" shouted another. "He's trying to climb upon the ice. Hurrah! he's on his feet again!" With that the whole company of spectators shouted for joy.

Joe had managed to regain his plank as well as to climb upon a cake of ice before the fields around could crush him, and now moving cautiously, he made his way, little by little toward the island.

"Hurrah! Hurrah! he's there at last!" shouted the people on the shore.

"But will he get back again?" was the question each one asked himself a moment later.

Having reached the island, Joe very well knew that the more difficult part of his task was still before him, for it was one thing for an active boy to work his way over floating ice, and quite another to carry a child and lead a woman upon a similar journey.

But Joe Lambert was quick-witted and "long-headed," as well as brave, and he meant to do all that he could to save these poor creatures for whom he had risked his life so heroically. Taking out his knife he made the woman cut her skirts off at the knees, so that she might walk and leap more freely. Then placing the baby in the basket which was strapped upon his back, he cautioned the woman against giving way to fright, and instructed her carefully about the method of crossing.

On the return journey Joe was able to avoid one great risk. As it was not necessary to land at any particular point, time was of little consequence, and hence when no large field of ice was at hand, he could wait for one to approach, without attempting to make use of the smaller ones. Leading the woman wherever that was necessary, he slowly made his way toward shore, drifting down the river, of course, while all the people of the town marched along the bank.

When at last Joe leaped ashore in company with the woman, and bearing her babe in the basket on his back, the people seemed ready to trample upon each other in their eagerness to shake hands with their hero.

Their hero was barely able to stand, however. Drenched as he had been in the icy river, the sharp March wind had chilled him to the marrow, and one of the village doctors speedily lifted him into his carriage which he had brought for that purpose, and drove rapidly away, while the other physician took charge of Mrs. Martin and the baby.

Joe was a strong, healthy fellow, and under the doctor's treatment of hot brandy and vigorous rubbing with coarse towels, he soon warmed. Then he wanted to saw enough wood for the doctor to pay for his treatment, and thereupon the doctor threatened to poison him if he should ever venture to mention pay to him again.

Naturally enough the village people talked of nothing but Joe Lambert's heroic deed, and the feeling was general that they had never done their duty toward the poor orphan boy. There was an eager wish to help him now, and many offers were made to him; but these all took the form of charity, and Joe would not accept charity at all. Four years earlier, as I have already said, he had refused to go to the poorhouse or to be "bound out," declaring that he could take care of himself; and when some thoughtless person had said in his hearing that he would have to live on charity, Joe's reply had been:

"I'll never eat a mouthful in this town that I haven't worked for if I starve." And he had kept his word. Now that he was fifteen years old he was not willing to begin receiving charity even in the form of a reward for his good deed.

One day when some of the most prominent men of the village were talking to him on the subject Joe said:

"I don't want anything except a chance to work, but I'll tell you what you may do for me if you will. Now that poor Martin is dead the ferry privilege will be to lease again, I'd like to get it for a good long term. Maybe I can make something out of it by being always ready to row people across, and I may even be able to put on something better than a skiff after awhile. I'll pay the village what Martin paid."

The gentlemen were glad enough of a chance to do Joe even this small favor, and there was no difficulty in the way. The authorities gladly granted Joe a lease of the ferry privilege for twenty years, at twenty dollars a year rent, which was the rate Martin had paid.

At first Joe rowed people back and forth, saving what money he got very carefully. This was all that could be required of him, but it occurred to Joe that if he had a ferry boat big enough, a good many horses and cattle and a good deal of freight would be sent across the river, for he was a "long-headed" fellow as I have said.

One day a chance offered, and he bought for twenty-five dollars a large old wood boat, which was simply a square barge forty feet long and fifteen feet wide, with bevelled bow and stern, made to hold cord wood for the steamboats. With his own hands he laid a stout deck on this, and, with the assistance of a man whom he hired for that purpose, he constructed a pair of paddle wheels. By that time Joe was out of money, and work on the boat was suspended for awhile. When he had accumulated a little more money, he bought a horse power, and placed it in the middle of his boat, connecting it with the shaft of his wheels. Then he made a rudder and helm, and his horse-boat was ready for use. It had cost him about a hundred dollars besides his own labor upon it, but it would carry live stock and freight as well as passengers, and so the business of the ferry rapidly increased, and Joe began to put a little money away in the bank.

After awhile a railroad was built into the village, and then a second one came. A year later another railroad was opened on the other side of the river, and all the passengers who came to one village by rail had to be ferried across the river in order to continue their journey by the railroads there. The horse-boat was too small and too slow for the business, and Joe Lambert had to buy two steam ferry-boats to take its place. These cost more money than he had, but, as the owner of the ferry privilege, his credit was good, and the boats soon paid for themselves, while Joe's bank account grew again.

Finally the railroad people determined to run through cars for passengers and freight, and to carry them across the river on large boats built for that purpose; but before they gave their orders to their boat builders, they were waited upon by the attorneys of Joe Lambert, who soon convinced them that his ferry privilege gave him alone the right to run any kind of ferry-boats between the two villages which had now grown to such size that they called themselves cities. The result was that the railroads made a contract with Joe to carry their cars across, and he had some large boats built for that purpose.

All this occurred a good many years ago, and Joe Lambert is not called Joe now, but Captain Lambert. He is one of the most prosperous men in the little river city, and owns many large river steamers besides his ferry-boats. Nobody is readier than he to help a poor boy or a poor man; but he has his own way of doing it. He will never toss so much as a cent to a beggar, but he never refuses to give man or boy a chance to earn money by work. He has an odd theory that money which comes without work does more harm than good.

THE CHRISTMAS GIFT.

![[Illuminated letter] O](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/64.png)

How can I ever love you enough?

How was it, I wonder, that any one knew

I wanted a little dog, just like you?

With your jet black nose, and each sharp-cut ear,

And the tail you wag—O you are so dear!

Did you come trotting through all the snow

To find my door, I should like to know?

Or did you ride with the fairy team

Of Santa Claus, of which children dream,

Tucked all up in the furs so warm,

Driving like mad over village and farm,

O'er the country drear, o'er the city towers,

Until you stopped at this house of ours?

Did you think 'twas a little girl like me

You were coming so fast thro' the snow to see?

Well, whatever way you happened here,

You are my pet and my treasure dear—

Such a Christmas present! O such a joy!

Better than any kind of a toy!

Something that eats and drinks and walks,

And looks so lovely and almost talks;

With a face so comical and wise,

And such a pair of bright brown eyes!

I'll tell you something: The other day

I heard papa to my mamma say

Very softly, "I really fear

Our baby may be quite spoiled, my dear,

We've made of our darling such a pet,

I think the little one may forget

There's any creature beneath the sun

Beside herself to waste thought upon."

I'm going to show him what I can do

For a dumb little helpless thing like you.

I'll not be selfish and slight you, dear;

Whenever I can I shall keep you near.

SOME EDUCATED HORSES.

A NOD OF GREETING.

A NOD OF GREETING.![[Illuminated letter] O](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/64.png)

The plan looks quixotic, does it not? But one thing you may be sure of; he might have worse associates. There are grades of intellect—we will call it intellect, for it comes very near, so near that we never can know just where the fine shading off begins between a horse's brain and that of a man; and there are warm, loving equine hearts. Many horses are superior to many men; nobler, more honorable, quicker-witted, more loyal, and a thousand times more companionable. Would you not rather, if you had to live on Robinson Crusoe's island, have an intelligent, sympathetic horse and a devoted bright dog than some people you know? One is inclined to favor Hamerton's notion after seeing the Bartholomew Educated Horses, who can do almost anything but speak.

BUCEPHALUS TAKES THE HAT.

BUCEPHALUS TAKES THE HAT.I am writing this for boys and girls who love animals, and for those elderly people who are fond of them too, including the lady whom I overheard saying that she had been nine times to see the remarkable exhibition. The young folks were enthusiastic patrons of that little theatre in Boston, where for more than a hundred afternoons and evenings the "Professor," as he was called, showed off his four-footed pupils. One forenoon he set apart for a free entertainment of as many poor children as the house would hold, who went under the charge of the truant officers and had an overwhelming good time.

There were sixteen of the animals, counting a donkey; grays, bays, chestnut-colored beauties, and one who looked buff in the gaslight. In recalling them, I cannot say that there was a white-footed one. What consequence about white feet, you ask! Perhaps you know that they make that of some account in the horse bazaars of the East. The Turks say "two white fore feet are lucky; one white fore and hind foot are unlucky;" and they have a rhyme that runs—

One white foot, buy a horse,

Two white feet, try a horse,

Three white feet, look well about him,

Four white feet, do without him.

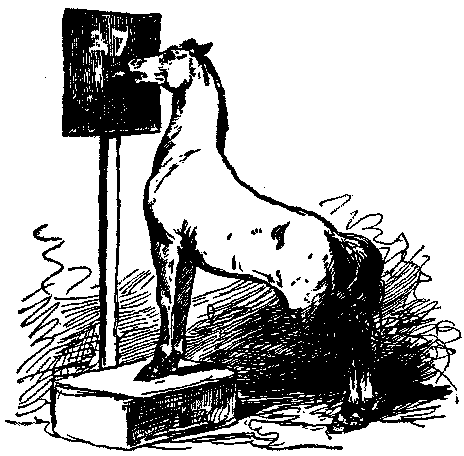

THE CHAIR IS BROUGHT.

THE CHAIR IS BROUGHT.They were all named. There was a Chevalier, a Prince, and a Pope; a little pet, Miss Nellie, who looked as if she would be ready to drink tea out of your saucer and kiss you after her fashion; Mustang, an irrepressible and rude savage from the Rio Grande region; Brutus, C�sar, and Draco; a Broncho beauty; a Sprite; a stately stepping Abdallah; Jim, who was a character; and a Bucephalus, after that storied steed who would suffer no one to ride but his master, the Great Alexander, but for him to mount, would kneel and wait.

It is perhaps needless and an insult to their intelligence for me to say that they all know their own names as well as you know yours. They know, too, their numbers when they are acting as soldiers formed in line waiting orders; the Professor passes along and checking them off with his forefinger numbers them, then falling back, calls out for certain ones to form into platoons, and they make no mistake. Their ears are alert, their senses sharp, their memory good. "Number Two," "Number Four," and so on, answer by advancing, as a soldier would respond to the roll-call.

They came around from the stable an hour before the performance and went up the stairs by which the audience went; and a crowd used to gather every afternoon and evening to see that remarkable and free feat.

PRINCE.

PRINCE.When the curtain rose there was to be seen a small stage carpeted ankle deep with saw-dust, where Professor Bartholomew purposed to have his horses act; first the part of a school, then of a court room, last a military drill and taking of a fort. They came in one after another, pretending, if that is not too strong a word, that they were on the way to school, and that was the playground; and there they played together, with such soft, graceful action, such caressing ways, and trippings as dainty as in "Pinafore," until at the ringing of a bell they came at once to order from their mixed-up, mazy pastime, and waited the arrival of their teacher, the Professor, who entered with a schoolmaster air, and gave the order.

"Bucephalus, take my hat, and bring me a chair!" as you might tell James or John to do the same, and with more promptness than they would have shown, Bucephalus came forward, took the hat between his teeth, carried it across the stage and placed it on a desk, and brought a chair.

SPRITE AS A MATHEMATICIAN.

SPRITE AS A MATHEMATICIAN.The master, seating himself, began the business of the day, saying, "The school will now form two classes; the large scholars will go to the left, the small ones to the right;" and six magnificent creatures separated themselves from the group huddled together and went as they were bid, while Nellie, the mustang, and other little ones, filed off to the opposite side, and placed themselves in a row, with their heads turned away from the stage. And there they remained, generally minding their business, though sometimes one would get out of position, look around, or give his neighbor a nudge which brought out a reprimand: "Pope, what are you doing?" "Brutus, you need not look around to see what I am about!" "Sprite, you let Mustang alone!" "Mustang, keep in your place!"

He then called for some one to come forward and be monitor, and Prince volunteered, was sent to the desk for some papers, tried to raise the lid, and let it drop, pretending that he couldn't, but after being sharply asked what he was so careless for, did it, and then brought a handkerchief and made a great ado about wanting to have something done with it, which proved to be tying it around his leg. Meanwhile one of the horses behaved badly, whereupon the teacher said, "I see you are booked for a whipping," and the culprit came out in the floor, straightened himself, and received without wincing what seemed to be a severe whipping; but in reality it was all done with a soft cotton snapper, which made more sound than anything else.

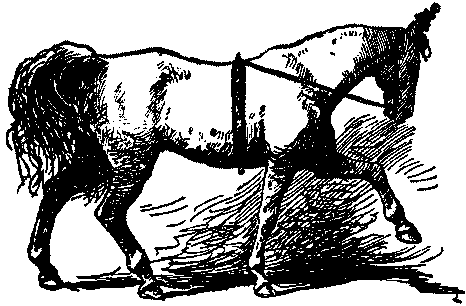

ABDALLAH PACES.

ABDALLAH PACES.Mustang was called upon to ring the bell, a good-sized dinner-bell, for the blackboard exercises by Sprite. He, too, made believe he couldn't, seized it the wrong way, dropped it, picked it up wrong end first, was scolded at, then took it by the handle, gave it a vigorous shake, and after letting it fall several times, set it on the table. Meanwhile a platform was brought in supporting a tall post, at the top of which, higher than a horse could reach, was a blackboard having chalked on it a sum which was not added up correctly. Sprite, being requested to wipe it out, took the sponge from the table, and planting her fore-feet on the platform, stretched her head up, and by desperate passes succeeded in wiping out a part of the figures, and started to leave, but seeing that some remained, went back and erased them.

One day she went through a process which showed conclusively that horses can reason. She dropped the sponge the first thing, and it fell down behind the platform out of her sight. She got down, and looked about in the saw-dust for it, the audience curiously watching to see what she would do next. She was evidently much perplexed. She knew perfectly well that her duty would not be fulfilled until she had rubbed the figures out, and the sponge was not to be found. Mr. Bartholomew said nothing, gave her no look or hint or sign to help her out of her predicament, but sat in his chair and waited. At last she deliberately stepped on the platform again, stretched her head up and wiped the figures out with her mouth, at which the audience applauded as if they would bring the roof down. That was something clearly not in the programme, but a bit of independent reasoning. Yet, having done so much, she knew that something was not right. About that sponge—what had become of it? It was her business to lay it on the table when she was through using it. She hesitated, looked this way and that, started to go, came back, dreadfully puzzled and uncertain, suddenly spied it, set her teeth in it, put it on the table, and went to her place, with a clear conscience, no doubt, and the people cheered more wildly than before.

A GAME OF LEAP-FROG.

A GAME OF LEAP-FROG.This was to me one of the most interesting things I witnessed; and connecting it with some facts Mr. Bartholomew communicated, it was doubly so.

NELLIE ROLLS THE BARREL OVER THE "TETER."

NELLIE ROLLS THE BARREL OVER THE "TETER."He said that it was his practice not to interfere or help; the horse knew just what she was to do, and he preferred to wait and let her think it out for herself. The other horses all knew too if there was any failure or mistake, and the offender was closely watched by them, and in some way reproved by them if they could get the opportunity, and at times this little by-play became very amusing.

After this was most exquisite dancing by Bucephalus, and by C�sar, whose steppings were in perfect rhythm to the music. Then the latter turned in a circle to the right or the left and walked around defining the figure eight, just as any one in the audience chose to request; and Abdallah came in with a string of bells around her, and paced, cantered, galloped, trotted, marched or walked as the word was given. The horses were generally expected to come to the footlights and bow to the audience at the close of any feat; occasionally one would forget to do this, and then some of his comrades would shoulder or buffet him, or Mr. Bartholomew would give a reminder, "That is not all, is it?" and back would come the delinquent, and bow and bow twenty times as fast as he could, as if there could not be enough of it. At the close of one scene all the horses came up to the front in a line, and leaning over the rope which was stretched there to keep them from coming down on the people's heads, would bow, and bow again, and it was a wonderfully pretty sight to see.

A game of leap frog was announced. "There are four of the horses that jump," said Mr. Bartholomew. They like this least of any of their feats, and those who can do it best are most timid. At first one horse is jumped over, then two, three, are packed closely together, and little Sprite clears them all at one flying leap, broad-backed and much taller than herself though they are. Those who do not want to try it beg off by a pretty pantomime, and Sprite is encouraged by her master, who pats her first and seems to be saying something in her ear. They like to get approval in the way of a caress, but beyond that they are in no way rewarded.

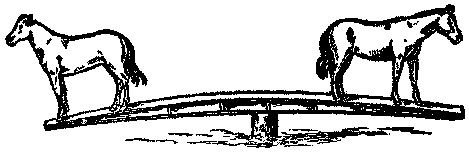

PRINCE AND POPE PLAY AT SEE-SAW.

PRINCE AND POPE PLAY AT SEE-SAW.Next Nellie rolled a barrel over a "teter plank" with her fore-feet, and Prince and Pope performed the difficult feat, and one which required mutual understanding and confidence, of see-sawing away up in air on the plank; first face to face, carefully balancing, and then the latter slowly turned on the space less than twenty inches wide, without disturbing the delicate poise. This he considers one of the most remarkable, because each horse must act with reference to the other, and the understanding between them must be so perfect that no fatal false movement can be made.

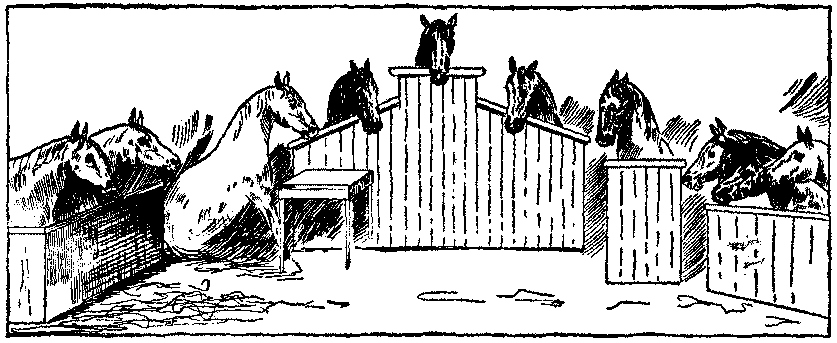

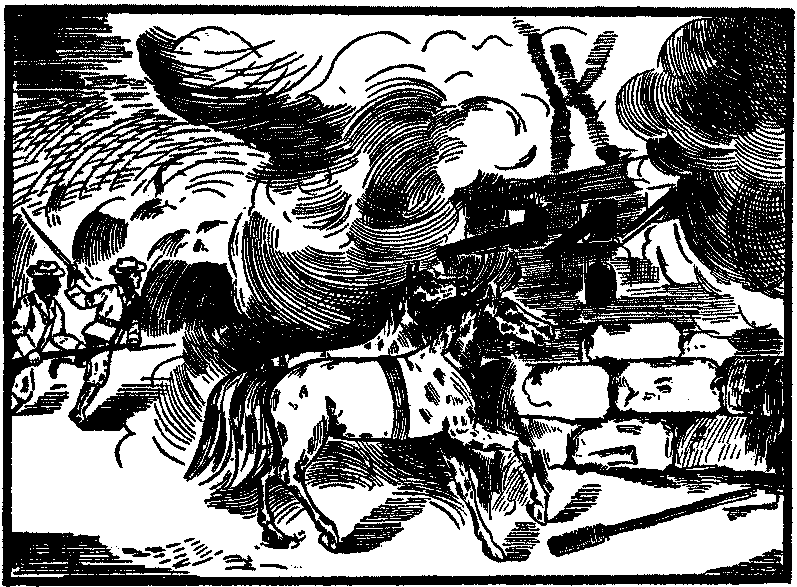

One of the grand tableaux represents a court scene with the donkey set up in a high place for judge, the jury passing around from mouth to mouth a placard labelled "Not Guilty," and the releasing of the prisoner from his chain. But the military drill exceeds all else by the brilliance of the display and the inspiring movements and martial air. Mr. Bartholomew in military uniform advancing like a general, disciplined twelve horses who came in at bugle call, with a crimson band about their bodies and other decorations, and went through evolutions, marchings, counter-marchings, in single file, by twos, in platoons, forming a hollow square with the precision of old soldiers. They liked it too, and were proud of themselves as they stepped to the music. The final act was a furious charge on a fort, the horses firing cannon, till in smoke and flame, to the sound of patriotic strains, the structure was demolished, the country's flag was saved, caught up by one horse, seized by another, waved, passed around, and amidst the excitement and confusion of a great victory, triumphant horses rushing about, the curtain fell.

THE GREAT COURT SCENE.

THE GREAT COURT SCENE.It was from first to last a wonderful exhibition of horse intelligence.

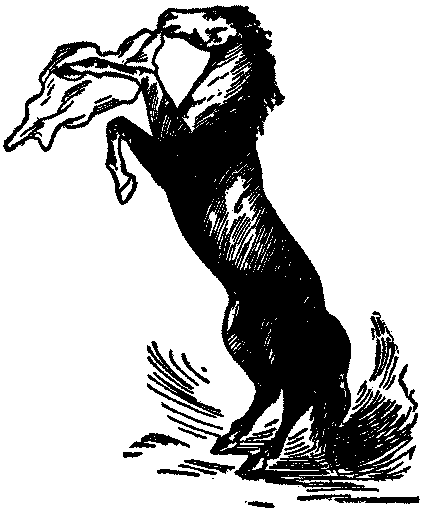

Trained horses, that is, trained for circus feats at given signals, are no novelty. Away back in the reign of one of the Stuarts, a horse named Morocco was exhibited in England, though his tricks were only as the alphabet to what is done now. And long before Rarey's day, there was here and there a man who had a sort of magnetic influence, and could tame a vicious horse whom nobody else dared go near. When George the Fourth was Prince of Wales, he had a valuable Egyptian horse who would throw, they said, the best rider in the world. Even if a man could succeed in getting on his back, it was not an instant he could stay there. But there came to England on a visit a distinguished Eastern bey, with his mamelukes, who, hearing of the matter which was the talk of the town, declared that the animal should be ridden. Accordingly many royal personages and noblemen met the Orientals at the riding house of the Prince, in Pall Mall, a mameluke's saddle was put on the vicious creature, who was led in, looking in a white heat of fury, wicked, with danger in his eyes, when, behold, the bey's chief officer sprung on his back and rode for half an hour as easily as a lady would amble on the most spiritless pony that ever was bridled.

STRETCHING HIMSELF.

STRETCHING HIMSELF.Some men have a tact, a way with animals, and can do anything with them. It is a born gift, a rare one, and a precious one. There was a certain tamer of lions and tigers, Henri Marten by name, who lately died at the age of ninety, who tamed by his personal influence alone. It was said of him in France, that at the head of an army he "might have been a Bonaparte. Chance has made a man of genius a director of a menagerie."

Professor Bartholomew was ready to talk about his way, but a part of it is the man himself. He could not make known to another what is the most essential requisite. He, too, brought genius to his work; besides that, a certain indefinable mastership which animals recognize, love for them, and a vast amount of perseverance and patient waiting. It is a thing that is not done in a day.

He was fond of horses from a boy, and began early to educate one, having a remarkable faculty for handling them; so that now, after thirty years of it, there is not much about the equine nature that he does not understand. He trained a company of Bronchos, which were afterwards sold; and since then he has gradually got together the fifteen he now exhibits, and he has others in process of training. He took these when they were young, two or three years old; and not one of them, except Jim, who has a bit of outside history, has ever been used in any other way. They know nothing about carriages or carts, harness or saddle; they have escaped the cruel curb-bits, the check reins and blinders of our civilization. Fortunate in that respect. And they never have had a shoe on their feet. Their feet are perfect, firm and sound, strong and healthy and elastic; natural, like those of the Indians, who run barefoot, who go over the rough places of the wilds as easily as these horses can run up the stairs or over the cobble stones of the pavement if they were turned loose in the street.

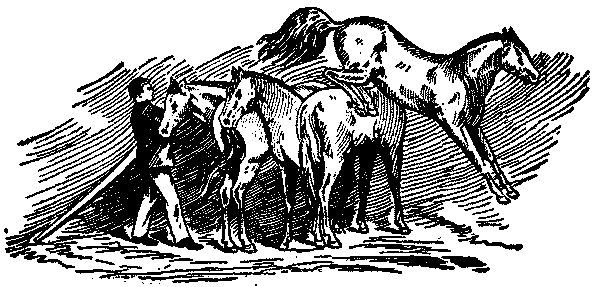

MILITARY DRILL.

MILITARY DRILL.It was a pleasure to know of their life-long exemption from all such restraints. That accounted in great measure for their beautiful freedom of motion, for that wondrous grace and charm. Did you ever think what a complexity of muscles, bones, joints, tendons and other arrangements, enter into the formation of the knees, hoofs, legs of a horse; what a piece of mechanism the strong, supple creature is?

These have never had their spirits broken; have never been scolded at or struck except when a whip was necessary as a rod sometimes is for a child. The hostlers who take care of them are not allowed to speak roughly. "Be low-spoken to them," the master says. In the years when he was educating them he groomed and cared for them himself, with no other help except that of his two little sons. No one else was allowed to meddle with them; and, necessarily, they were kept separate from other horses. Now, wherever they are exhibiting, he always goes out the first thing in the morning to see them. He passes from one to another, and they are all expecting the little love pats and slaps on their glossy sides, the caressings and fondlings and pleasant greetings of "Chevalier, how are you, old fellow?" "Abdallah, my beauty," and, "Nellie, my pet!" Some are jealous, Abdallah tremendously so, and if he does not at once notice her, she lays her ears back, shows temper, and crowds up to him, determined that no other shall have precedence.

A PRETTY TABLEAU.

A PRETTY TABLEAU.They are not "thorough-breds." Those, he said, were for racers or travellers; yet of fine breeds, some choice blood horses, some mixed, one a mustang, who at first did not know anything that was wanted of him.

"Why," said he, "at first some of them would go up like pop corn, higher than my head. But I never once have been injured by one of them except perhaps an accidental stepping on my foot. They never kick; they don't know how to kick. You can go behind them as well as before, and anywhere."

In buying he chose only those whose looks showed that they were intelligent. "But how did he know, by what signs?" queried an all-absorbed "Dumb Animals" woman.

"Oh, dear," he said, "why, every way; the eyes, the ears, the whole face, the expression, everything. No two horses' faces look alike. Just as it is with a flock of sheep. A stranger would say, 'Why, they are all sheep, and all alike, and that is all there is to it;' but the owner knows better; he knows every face in the flock. He says, 'this is Jenny, and that is Dolly, there is Jim, and here's Nancy.' Oh, land, yes! they are no more alike than human beings are, disposition or anything. Some have to be ordered, and some coaxed and flattered. Yes, flattered. Now if two men come and want to work for me, I can tell as soon as I cast my eyes on them. I say to one, 'Go and do such a thing;' but if I said it to the other, he'd answer 'I won't; I'm not going to be ordered about by any man.' Horses are just like that. A horse can read you. If you get mad, he will. If you abuse him, he will do the same by you, or try to. You must control yourself, if you would control a horse."

They must be of superior grade, "for it's of no use to spend one's time on a dull one. It does not pay to teach idiots where you want brilliant results, though all well enough for a certain purpose."

Some of these he had been five years in educating to do what we saw. Some he had taught to do their special part in one year, some in two. The first thing he did was to give the horse opportunity and time to get well acquainted with him; in his words, "to become friends. Let him see that you are his friend, that you are not going to whip him. You meet him cordially. You are glad to see him and be with him, and pretty soon he knows it and likes to be with you. And so you establish comradeship, you understand each other. Caress him softly. Don't make a dash at him. Say pleasant things to him. Be gentle; but at the same time you must be master." That is a good basis. And then he teaches one thing at a time, a simple thing, and waits a good while before he brings forward another; does not perplex or puzzle the pupil by anything else till that is learned, and some of the first words are "come," "stand," "remain."

What a horse has once learned he never or seldom forgets. Mr. Bartholomew thinks it is not as has sometimes been said, because a horse has a memory stronger than a man, "but because he has fewer things to learn. A man sees a million things. A horse's mind cannot accommodate what a man's can, so those things he knows have a better chance. Those few things he fixes. His memory fastens on them. I once had a pony I had trained, which was afterwards gone from me three years. At the end of that time I was in California exhibiting, and saw a boy on the pony. I tried to buy him, but the boy who had owned him all that time, refused to part with him; however, I offered such a price that I got him, and that same evening I took him into the tent and thought I would see what he remembered. He went through all his old tricks (besides a few I had myself forgotten) except one. He could not manage walking on his hind feet the distance he used to. Another time I had a trained horse stolen from me by the Indians, and he was off in the wilds with them a year and a half. One day, in a little village—that was in California too—I saw him and knew him, and the horse knew me. I went up to the Indian who had him and said, 'That is my horse, and I can prove it.' Out there a stolen horse, no matter how many times he has changed hands, is given up, if the owner can prove it. The Indian said, 'If you can, you shall have him, but you won't do it.' I said, 'I will try him in four things; I will ask him to trot three times around a circle, to lie down, to sit up, and to bring me my handkerchief. If he is my horse, he will do it.' The Indian said, 'You shall have him if he does, but he won't!' By this time a crowd had got together. We put the horse in an enclosure, he did as he was told, and I had him back."

Mr. Bartholomew said, "My motto in educating them is, 'Make haste slowly;' I never require too much, and I never ask a horse to do what he can't do. That is of no use. A horse can't learn what horses are not capable of learning; and he can't do a thing until he understands what you mean, and how you want it done. What good would it do for me to ask a man a question in French if he did not know a word of the language? I get him used to the word, and show him what I want. If it is to climb up somewhere, I gently put his foot up and have him keep it there until I am ready to have it come down, and then I take it down myself. I never let the horse do it. The same with other things, showing him how, and by words. They know a great number of words. My horses are not influenced by signs or motions when they are on the stage. They use their intelligence and memory, and they associate ideas and are required to obey. They learn a great deal by observing one another. One watches and learns by seeing the others. I taught one horse to kneel, by first bending his knee myself, and putting him into position. After he had learned, I took another in who kept watch all the time, and learned partly by imitation. They are social creatures; they love each other's company."

Most of these horses have been together now for several years, and are fond of one another. They appear to keep the run of the whole performance, and listen and notice like children in a school when one or more of their number goes out to recite. It was extremely interesting to observe them when the leap-frog game was going on. Owing to the smallness of the stage, it was difficult for the horse who was to make the jump to get under headway, and several times poor Sprite, or whichever it was, would turn abruptly to make another start, upon which every horse on her side would dart out for a chance at giving her a nip as she went by. They all seemed throughout the entire exhibition to feel a sort of responsibility, or at least a pride in it, as if "this is our school. See how well Bucephalus minds, or how badly Brutus behaves! This is our regiment. Don't we march well? How fine and grand, how gallant and gay we are!" And the wonder of it all is, not so much what any one horse can do, or the sense of humor they show, or the great number of words they understand, but the mental processes and nice calculation they show in the feats where they are associated in complex ways, which require that each must act his part independently and mind nothing about it if another happens to make a mistake.

VICTORY.

VICTORY.To obtain any adequate representation of these horses while performing, it was necessary that it be done by process called instantaneous photographing. You are aware that birds and insects are taken by means of an instrument named the "photographic revolver," which is aimed at them. Recently an American, Mr. Muybridge, has been able to photograph horses while galloping or trotting, by his "battery of cameras," and a book on "the Horse in Motion" has for its subject this instantaneous catching a likeness as applied to animals. But how could any process, however swift, or ingenious, or admirable, do full justice to the grace and spirit, the all-alive attitudes and varieties of posture, the dalliance and charm, the freedom in action?

THE STORMING OF THE FORT.

THE STORMING OF THE FORT.Professor Bartholomew gave his performances the name of "The Equine Paradox." He now has his beautiful animals in delightful summer quarters at Newport, where they are counted among the "notable guests." He has the Opera House there for his training school for three months, preparing new ones for next winter's exhibition, and keeping the old ones in practice. It is pleasant to know that he cares so faithfully for their health as to give them a home through the warm weather in that cool retreat by the sea.

AFTER THE PLAY.

AFTER THE PLAY.QUESTIONS.

![[Illuminated letter] C](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/59.png)

Can you put the apple again on the bough, which fell at our feet to-day?

Can you put the lily-cup back on the stem, and cause it to live and grow?

Can you mend the butterfly's broken wing, that you crushed with a hasty blow?

Can you put the bloom again on the grape, or the grape again on the vine?

Can you put the dewdrops back on the flowers, and make them sparkle and shine?

Can you put the petals back on the rose? If you could, would it smell as sweet?

Can you put the flour again in the husk, and show me the ripened wheat?

Can you put the kernel back in the nut, or the broken egg in its shell?

Can you put the honey back in the comb, and cover with wax each cell?

Can you put the perfume back in the vase, when once it has sped away?

Can you put the corn-silk back on the corn, or the down on the catkins—say?

You think that my questions are trifling, dear? Let me ask you another one:

Can a hasty word ever be unsaid, or a deed unkind, undone?

THE BRAVEST BOY IN TOWN.

![[Illuminated letter] H](https://subjectcoach.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/stories/16171-h/61.png)

And his name was Jamie Brown;

But it changed one day, so the neighbors say,

To the "Bravest Boy in Town."

'Twas the time when the Southern soldiers,

Under Early's mad command,

O'er the border made their dashing raid

From the north of Maryland.

And Chambersburg unransomed

In smouldering ruins slept,

While up the vale, like a fiery gale,

The Rebel raiders swept.

And a squad of gray-clad horsemen

Came thundering o'er the bridge,

Where peaceful cows in the meadows browse,

At the feet of the great Blue Ridge;

And on till they reached the village,

That fair in the valley lay,

Defenseless then, for its loyal men,

At the front, were far away.

"Pillage and spoil and plunder!"

This was the fearful word

That the Widow Brown, in gazing down

From her latticed window, heard.

'Neath the boughs of the sheltering oak-tree,

The leader bared his head,