« back

W.H.G. Kingston and Henry Frith

"Notable Voyagers"

Chapter One.

Introduction—A.D. 1486.

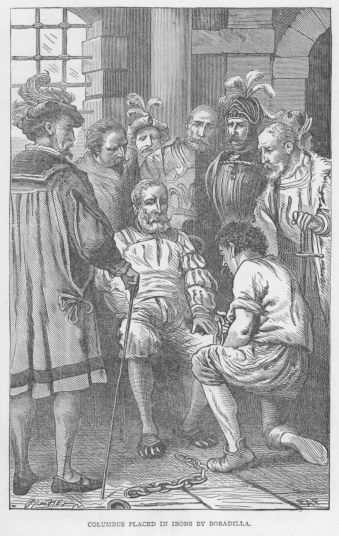

Columbus before the conclave of Professors at Seville—His parentage and early history—Battle with Venetian galleys—Residence in Portugal—Marries widow of a navigator—Grounds on which he founded his theory—Offers his services to the King of Portugal—His offer declined—Sends his brother Bartholomew to Henry the Seventh of England—Don John sends out a squadron to forestall him—Sets off for Spain—Introduced by the Duke of Medina Celi to Queen Isabella—She encourages him—Plan for the recovery of the Holy Sepulchre—His long detention at Court while Ferdinand and Isabella are engaged in the war against the Moors of Granada—A hearing at length afforded him—His demands refused—Leaves the Court in poverty and visits Palos on his way to France—Met by Juan Perez, Prior of the Rabida convent—The Prior listens to his plans—Introduces him to the Pinzons, and informs the Queen of his intended departure—Sent for back at Court—All his demands agreed to—Authority given him to fit out a squadron.

In the year 1486 a council of learned professors of geography, mathematics, and all branches of science, erudite friars, accomplished bishops, and other dignitaries of the Church, were seated in the vast arched hall of the old Dominican convent of Saint Stephen in Salamanca, then the great seat of learning in Spain. They had met to hear a simple mariner, then standing in their midst, propound and defend certain conclusions at which he had arrived regarding the form and geography of the earth, and the possibility, nay, the certainty, that by sailing west, the unknown shores of Eastern India could be reached. Some of his hearers declared it to be grossly presumptuous in an ordinary man to suppose, after so many profound philosophers and mathematicians had been studying the world, and so many able navigators had been sailing about it for years past, that there remained so vast a discovery for him to make. Some cited the books of the Old Testament to prove that he was wrong, others the explanations of various reverend commentators. Doctrinal points were mixed up with philosophical discussions, and a mathematical demonstration was allowed no weight if it appeared to clash with a text of Scripture or comment of one of the fathers.

Although Pliny and the wisest of the ancients had maintained the possibility of an antipodes in the southern hemisphere, these learned gentlemen made out that it was altogether a novel theory.

Others declared that to assert there were inhabited lands on the opposite side of the globe would be to maintain that there were nations not descended from Adam, as it would have been impossible for them to have passed the intervening ocean, and therefore discredit would be thrown on the Bible.

Again, some of the council more versed in science, though admitting the globular form of the earth, and the possibility of an opposite habitable hemisphere, maintained that it would be impossible to arrive there on account of the insupportable heat of the torrid zone; besides which, if the circumference of the earth was as great as they supposed, it would require three years to make the voyage.

Several, with still greater absurdity, advanced as an objection that should a ship succeed in reaching the extremity of India, she could never get back again, as the rotundity of the globe would present a kind of mountain up which it would be impossible for her to sail even with the most favourable wind.

The mariner replied in answer to the scriptural objection that the inspired writers were not speaking technically as cosmographers, but figuratively, in language addressed to all comprehensions, and that the commentaries of the fathers were not to be considered as philosophical propoundings, which it was necessary either to admit or refute.

In regard to the impossibility of passing the torrid zone, he himself stated that he had voyaged as far as Guinea under the equinoxial line, and had found that region not only traversable, but abounding in population, fruits, and pasturage.

Who was this simple mariner who could thus dare to differ from so many learned sages? His person was commanding; his demeanour elevated; his eye kindling; his manner that of one who had a right to be heard, while a rich flow of eloquence carried his hearers with him. His countenance was handsome; his hair already blanched by thought, toil, and privation.

He was no other than Columbus, who, after his proposals had been rejected by the Court of Portugal, had addressed himself to that of Spain, and had, year after year, waited patiently to obtain a hearing from Ferdinand and Isabella, then occupied in their wars against the Moors.

He had been a seaman from the age of fourteen. He was born in the city of Genoa about the year 1435, where his father, Dominico Colombo, carried on the business of a wool comber, which his ancestors had followed for several generations. He was the eldest of three brothers, the others being Bartholomew and Diego. He had at an early age evinced a desire for the sea, and accordingly his education had been mainly directed to fit him for maritime life.

His first voyages were made with a distant relative named Colombo, a hardy veteran of the seas, who had risen to some distinction by his bravery.

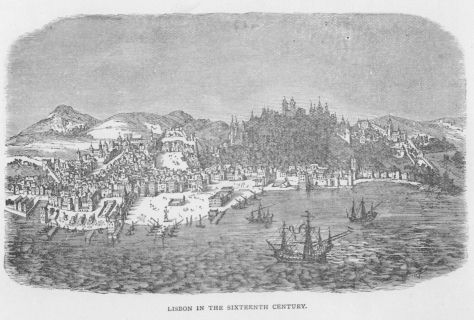

Under this relative young Christopher saw much service, both warlike and in trading voyages, until he gained command of a war ship of good size. When serving in the squadron of his cousin information was brought that four richly-laden Venetian galleys were on their return voyage from Flanders. The squadron lay in wait for them off the Portuguese coast, between Lisbon and Cape Saint Vincent. A desperate engagement ensued; the vessels grappled each other. That commanded by Columbus was engaged with a huge Venetian galley. Hand-grenades and other fiery missiles were thrown on board her, and the galley was wrapped in flames. So closely were the vessels fastened together, that both were involved in one conflagration. The crews threw themselves into the sea. Columbus seized an oar, and being an expert swimmer, reached the shore, though fully two leagues distant. On recovering he made his way to Lisbon. Possibly he may have resided there previously; certain it is that he there married a lady, the daughter of a distinguished navigator, from whose widow he obtained much information regarding the voyages and expeditions of her late husband, as well as from his papers, charts, journals, and memoranda.

Having become naturalised in Portugal, he sailed occasionally on voyages to the coast of Guinea, and when on shore supported his family by making maps and charts, which in those days required a degree of knowledge and experience sufficient to entitle the possessor to distinction.

He associated with various navigators, and he noted down all he heard. It was said by some that islands had been

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, two great travellers, Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville, journeyed eastward over a large portion of Asia, and had given vivid descriptions of the magnificence of its cities and scenery. Marco Polo especially had described two large islands, Ontilla and Cipango, the latter undoubtedly Japan, which it was expected would be the first reached by a navigator sailing westward.

A Portuguese pilot, Martin Vicenti, after sailing four hundred and fifty-two leagues to the west of Cape Saint Vincent, had found a piece of carved wood evidently laboured with an iron instrument, and as probably the wind had drifted it from the west, it might have come from some unknown land in that direction. A brother-in-law of Columbus had likewise found a similar piece of wood drifted from the same quarter. Reeds of enormous size, such as were described by Ptolemy to grow in India, had been picked up, and trunks of huge pine-trees had been driven on the shores of the Azores, such as did not grow on any of those islands. The bodies of two dead men, whose features differed from those of any known race of people, had been cast on the island of Flores. There were islands, it was rumoured, still farther west than those visited, and a mariner sailing from Port Saint Mary to Ireland asserted that he had seen land to the west, which the ship’s company took to be some extreme point of Tartary.

These facts being made known to Columbus, served to strengthen his opinion. The success indeed of his undertaking depended greatly on two happy errors: the imaginary extent of Asia to the east, and the supposed smallness of the earth. A deep religious sentiment mingled with his meditations. He looked upon himself as chosen by Heaven for the accomplishment of its purposes, that the ends of the earth might be brought together, and all nations and tongues united under the banner of the Redeemer.

The enthusiastic nature of his conceptions gave an elevation to his spirit, and dignity and eloquence to his whole demeanour. He never spoke in doubt or hesitation, but with as much certainty as if his eyes had beheld the promised land.

No trial or disappointment could divert him from the steady pursuit of his object. That object, it is supposed, he meditated as early as the year 1474, though as yet it lay crude and immatured in his mind. Shortly afterwards, in the year 1477, he made a voyage to the north of Europe, navigating one hundred leagues beyond Thule, when he reached an island as large as England, generally supposed to have been Iceland.

In vain he had applied to Don John the Second, who ascended the throne of Portugal in 1481. That king was so deeply engaged in sending out expeditions to explore the African coast that his counsellors advised him to confine his efforts in that direction. He would, however, have given his consent had not Columbus demanded such high and honourable rewards as were considered inadmissible.

To his eternal disgrace the Bishop of Ceuta advised that Columbus should be kept in suspense while a vessel was secretly dispatched in the direction he pointed out, to ascertain if there was any truth in his story. This was actually done, until the caravel meeting with stormy weather, and an interminable waste of wild tumbling waves, the pilots lost courage and returned.

Columbus, indignant at this attempt to defraud him, his wife having died some time previously, resolved to abandon the country which had acted so treacherously. He first sent his brother Bartholomew to make proposals to Henry the Seventh, King of England; but that sovereign rejected his offers, and having again made a proposal to Genoa, which, from the reverses she had lately received, she was unable to accept, he turned his eyes to Spain.

The great Spanish Dukes of Medina Sidonia and Medina Coeli, were at first inclined to support him, and the latter spoke of him to Queen Isabella, who giving a favourable reply, Columbus set off for the Spanish Court, then at Cordova.

The sovereigns of Castile and Arragon were, however, so actively engaged in carrying on the fierce war with the Moors of Grenada, that they were unable to give due attention to the scheme of the navigator, while their counsellors generally derided his proposals.

The beautiful and enlightened Isabella treated him from the first with respect, and other friends rose up who were ready to give him support.

Wearied and discouraged by long delays, however, he had again opened up negotiations with the King of Portugal, and had been requested by that monarch to return there. He had also received a letter from Henry the Seventh of England, inviting him to his Court, and holding out promises of encouragement, when he was again summoned to attend the Castilian Court, and a sum of money was sent him to defray his expenses, King Ferdinand probably fearing that he would carry his proposals to a rival monarch, and wishing to keep the matter in suspense until he had leisure to examine it.

He accordingly repaired to the Court of Seville. While he was there two monks arrived with a message from the Grand Soldan of Egypt, threatening to put to death all the Christians and to destroy the Holy Sepulchre if the Spanish sovereigns did not desist from war against Grenada.

The menace had no effect in altering their purpose, but it aroused the indignation of the Spanish cavaliers, and still more so that of Columbus, and made them burn with ardent zeal once more to revive the contest of faith on the sacred plains of Palestine. Columbus had indeed resolved, should his projected enterprise prove successful, to devote the profits from his anticipated discoveries to a crusade for the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre from the power of the infidels.

During the latter part of the year 1490 Ferdinand and Isabella were engaged in celebrating the marriage of their eldest daughter, the Princess Isabella, with Prince Don Alonzo, heir apparent of Portugal. Bearing these long and vexatious delays as he had before done, Columbus supported himself chiefly by making maps and charts, occasionally assisted from the purse of his friend Diego de Deza.

The year was passing on. Columbus was kept in a state of irritating anxiety at Cordova, when he heard that the sovereigns were about to commence that campaign which ended in the expulsion of the Moors from Spain. Aware that many months must pass before they would give their minds to the subject if he allowed the present moment to slip by, he pressed for a decisive reply to his proposals with an earnestness that would admit of no evasion.

The learned men of the council were directed to express their opinion of the enterprise. The report of each was unfavourable, although the worthy friar Diego de Deza, tutor to Prince John, and several others, urged the sovereigns not to lose the opportunity of extending their dominions and adding so greatly to their glory.

Again, however, Columbus was put off. Having no longer confidence in the vague promises which had hitherto been made, he turned his back on Seville, resolved to offer to the King of France the honour of carrying out his magnificent undertaking.

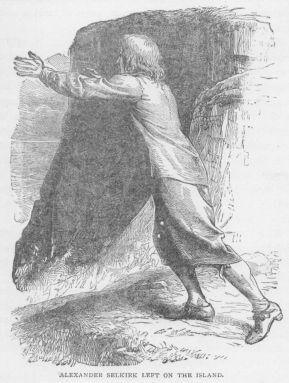

Leaving Seville, his means exhausted, he travelled on foot, leading his young son Diego by the hand, to the sea-port of Palos de Moguer in Andalusia. Weary and exhausted, he stopped to ask for bread and water at the gate of the ancient Franciscan convent of Santa Maria de Rabida.

The Prior, Juan Perez de Marchena, happening to come up, and remarking the appearance of the stranger, entered into conversation with him. The Prior, a man of superior information, was struck with the grandeur of his views, and when he found that the navigator was on the point of abandoning Spain to seek patronage in the Court of France, and that so important an enterprise was about to be lost for ever to the country, his patriotism took the alarm. He entertained Columbus as his guest, and invited a scientific friend—a physician—Garcia Fernandez, to converse with him.

Fernandez was soon captivated by his conversation. Frequent conferences took place, at which several of the veteran mariners of Palos were present. Among these was Martin Alonzo Pinzon, the head of a family of wealthy and experienced navigators. Facts were related by some of the mariners in support of the theory of Columbus, and so convinced was Pinzon of the feasibility of his project, that he offered to engage in it with purse and person. The Prior, who had once been confessor to the Queen, was confirmed in his faith by the opinions expressed, and he proposed writing to her immediately, and entreated Columbus to delay his journey until an answer could be received.

It was decided to send Sebastian Rodriguez, a shrewd and clever pilot, to Santa Fé, where the Queen then was. Isabella had always been favourable to Columbus, and the Prior received a reply desiring that he himself should repair to Court. He went, and, seconded by the Marchioness of Moya and other old friends, so impressed the Queen with the importance of the undertaking, that she desired Columbus might be sent for, and ordered that seventy-two dollars, equal to two hundred and sixteen of the present day, might be forwarded to him, to bear his travelling expenses.

With his hopes raised to the highest pitch, Columbus again repaired to Court; but so fully occupied was he with the grandeur of his enterprise, that he stipulated that he should be invested with the title and privilege of admiral, and viceroy over the countries he should discover, with one-tenth of all gains, either by trade or conquest. It must be remembered the pious and patriotic way—according to his notions—in which he intended to expend the wealth he hoped to acquire.

The courtiers were indignant, and sneeringly observed that his arrangement was a secure one, that he was sure of a command, and had nothing to lose.

On this he offered to furnish one-eighth of the cost, on condition of enjoying one-eighth of the profit. The King looked coldly on the affair, and once more the sovereigns of Spain declined the offer. Columbus was at length again about to set off on his journey to Palos, when the generous spirit of Isabella was kindled by the remarks of the Marchioness of Moya, supported by Louis de Saint Angel, Receiver of the Ecclesiastical Revenues in Arragon. She exclaimed, “I undertake the enterprise for my own crown of Castile, and will pledge my jewels to raise the necessary funds!”

This was the proudest moment in the life of Isabella, as it stamped her as the patroness of the great discovery.

Saint Angel assured her there was no necessity for pledging her jewels, and expressed his readiness to advance seventeen thousand florins. A messenger was dispatched to bring back the navigator, with the assurance that all he desired would be granted; and so, turning the reins of his mule, he hastened back with joyful alacrity to Santa Fé, confiding in the noble probity of the Queen.

Articles of agreement were drawn up by the royal secretary at once. Columbus was to have for himself during his life, and his heirs and successors for ever, the office of admiral of all lands and continents which he might discover.

Secondly: He was to be viceroy and governor-general over them.

Thirdly: He was to be entitled to receive for himself one-tenth of all pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and all other articles and merchandise obtained within this admiralty.

Fourthly: He or his lieutenant was to be the sole judge in all cases and disputes arising out of traffic between those countries and Spain.

Fifthly: He might then, and at all after times, contribute an eighth part of the expense in fitting out vessels to sail on this enterprise, and receive one-eighth part of the profit.

The latter engagement he fulfilled through the assistance of the Pinzons of Palos, and added a third vessel to the armament.

Thus, one-eighth of the expense attendant on this grand expedition, undertaken by a powerful nation, was actually borne by the individual who conceived it, and who likewise risked his life on its success.

The capitulations were afterwards signed by Ferdinand and Isabella on the 17th of April, 1492, when, in addition to the above articles, Columbus and his heirs were authorised to prefix the title of Don to their names.

It was arranged that the armament should be fitted out at the port of Palos, Columbus calculating on the co-operation of his friends Martin Alonzo Pinzon and the Prior of the convent.

Both Isabella and Columbus were influenced by a pious zeal for effecting the great work of salvation among the potentates and peoples of the lands to be discovered. He expected to arrive at the extremity of the ocean, and to open up direct communication with the vast and magnificent empire of the Grand Khan of Tartary. His deep and cherished design was the recovery of the Holy Sepulchre, which he meditated during the remainder of his life, and solemnly provided for in his will.

Let those who are disposed to faint under difficulties in the prosecution of any great and worthy undertaking, remember that eighteen years elapsed after the time that Columbus conceived his enterprise, before he was able to carry

Chapter Two.

First voyage of Columbus—A.D. 1492.

Columbus returns to Palos—Assisted by the Prior of La Rabida—The Pinzons agree to join him—Difficulty of obtaining ships and men—At length three vessels fitted out—Sails in the Santa Maria, with the Pinta and Nina, on 3rd August, 1492—Terrors and mutinous disposition of the crews—Reaches the Canary Islands—Narrowly escapes from a Portuguese squadron seat to capture him—Alarm of the crews increases—The squadron sails smoothly on—Columbus keeps two logs to deceive the seamen—Signs of land—Seaweed—Flights of birds—Birds pitch on the ship—Frequent changes in the tempers of the crews—Westerly course long held—Course altered to south-west—Pinzon fancies he sees land—Disappointment—Columbus sees lights at night—Morning dawns—San Salvador discovered—Natives seen—Columbus lands—Wonder of the natives—Proceeds in search of Cipango—Other islands visited, and gold looked for in vain—Friendly reception by the natives—Supplies brought off—Search for Saometo—Cuba discovered 20th October, 1492—Calls it Juana—Believes it to be the mainland of India—Sends envoys into the interior—Their favourable report of the fertility of the country—A storm—Deserted by Martin Pinzon in the Pinta—First view of Hispaniola—A native girl captured—Set free—Returns with large numbers of her countrymen—Arcadian simplicity of the natives.

Columbus hastened to Palos, where he was received as the guest of Fray Juan Perez, the worthy Prior of the convent of Rabida. The whole squadron with which the two sovereigns proposed to carry out their grand undertaking was to consist only of three small vessels. Two of these, by a royal decree, were to be furnished by Palos, the other by Columbus himself or his friends.

The morning after his arrival, Columbus, accompanied by the Prior, proceeded to the church of Saint George in Palos, where the authorities and principal inhabitants had been ordered to attend. Here the royal order was read by a notary public, commanding them to have two caravels ready

Orders were likewise read, addressed to the public authorities, and the people of all ranks and conditions in the maritime borders of Andalusia, commanding them to furnish supplies and assistance of all kinds for fitting out the caravels.

When, however, the nature of the service was explained, the owners of vessels refused to furnish them, and the seamen shrank from sailing into the wilderness of the ocean.

Several weeks elapsed, and not a vessel had been procured. The sovereigns therefore issued further orders, directing the magistrates to press into the service any caravel they might select, and to compel the masters and crews to sail with Columbus in whatever direction he should be sent.

Notwithstanding this nothing was done, until at length Martin Alonzo Pinzon, with his brother, Vincente Yanez Pinzon—both navigators of great courage and ability, and owners of vessels—undertook to sail on the expedition, and furnish one of the caravels required. Two others were pressed by the magistrates under the arbitrary mandate of the sovereigns.

The owners of one of the vessels, the Pinta, threw all possible obstacles in the way of her being fitted out. The caulkers performed their work in an imperfect manner, and even some of the seamen who had at first volunteered repented of their hardihood, and others deserted.

The example of the Pinzons at length overcame all opposition, and the three vessels, two of them known as caravels, not superior to the coasting craft of more modern days, were got ready by the beginning of August.

Columbus hoisted his flag on board the largest, the Santa Maria; the second, the Pinta, was commanded by Martin Alonzo Pinzon, accompanied by his brother Francisco Martin as pilot; and the third, the Nina, was commanded by Vincente Yafiez Pinzon. The other three pilots were Sancho Raiz, Pedro Alonzo Nino, and Bartolomeo Roldan.

Roderigo Sanches was inspector-general of the armament, and Diego de Arana chief alguazil. Roderigo de Escobar went as royal notary. In all, one hundred and twenty persons.

Columbus and his followers, having solemnly taken the communion, went on board their ships. Believing that their friends were going to certain death, the inhabitants of Paios looked on with gloomy apprehensions, which greatly affected the minds of the crew.

The little squadron set sail from Palos half an hour before sunrise on the 3rd of August, 1492, and steered a course for the Canary Islands. Columbus had prepared a chart by which to sail. On this he drew the coasts of Europe and Africa, from the south of Ireland to the end of Guinea, and opposite to them, on the other side of the Atlantic, the extremity of Asia, or rather India, as it was then called. Between them he placed the island of Cipango or Japan, which, according to Marco Polo, lay one thousand five hundred miles from the Atlantic coast. This island Columbus placed where Florida really exists. Though he saw his hopes of commencing the expedition realised, he had good reason to fear that his crews might at any moment insist on returning.

On the third day after sailing, it was discovered that the rudder of the Pinta was broken and unslung, probably a trick of her owners. The wind was blowing so strongly at the time that he could not render assistance, but Martin Alonzo Pinzon, being an able seaman, succeeded in securing it temporarily with ropes.

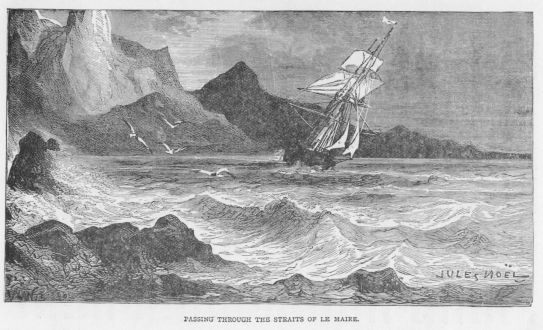

As the Pinta also leaked, Columbus put into the Canaries on the morning of the 9th of August, and was detained there three weeks, trying to obtain a better vessel. None being found, the lateen sails of the Pinta were altered into square sails. While here the crews were frightened by seeing flames burst out of the lofty peak of Teneriffe. Shortly after a vessel arrived from Ferro, which reported that three Portuguese caravels were watching to capture the squadron of Columbus, who, suspecting that the King of Portugal had formed a hostile plan in revenge for his having embarked in the service of Spain, immediately put to sea and stood away from the coast. He was now striking off from the frontier islands of the Old World into the region of discovery. For three days the squadron was detained by a calm. On the 9th of September he saw Ferro, the most western of the Canary Islands, where the Portuguese were said to be waiting for him, about nine leagues distant. At length, a breeze filling the sails of his ships, he was able to stand on his course, as he hoped, free of all danger. Chaos, mystery, and peril were before them. The hearts of his crew sank as they lost sight of land, and many of the seamen broke into loud lamentations. The Admiral tried to soothe their distress, and to inspire them with his own glorious anticipations by describing to them the magnificence of the countries to which he was about to conduct them, and the wealth and glory which would be theirs.

He now issued orders to the commanders of the other vessels that, in the event of separation, they should continue directly westward; but that, after sailing seven hundred leagues, they should lay by from midnight to daylight, as about that distance he confidently expected to find land.

As he foresaw the farther they sailed the more their vague terrors would increase, to deceive them, he kept two logs; one correct, retained for his own government, and the other open to general inspection, from which a certain number of leagues were daily subtracted from the sailing of the ships.

The crews, though no faint-hearted fellows, had not as yet learned to place confidence in him. The slightest thing alarmed them. When about one hundred and fifty leagues west of Ferro, they picked up part of the mast of a large vessel, and the crews fancied that she must have been wrecked drifting ominously to the entrance of those unknown seas.

About nightfall, on the 13th of September, he for the first time noticed the variation of the needle, which, instead of pointing to the north star, varied about half a point. He remarked that this variation of the needle increased as he advanced. He quieted the alarm of his pilots, when they observed this, by assuring them that the variation was not caused by any fallacy in the compass, but by the movement of the north star itself, which, like the other heavenly bodies, described a circle round the pole.

The explanation appeared so highly plausible and ingenious that it was readily received. On the 14th of September they believed that they were near land, from seeing a heron and a tropical bird, neither of which were supposed to venture far out to sea.

The following night the mariners were awestruck by beholding a meteor of great brilliancy—a common phenomenon in those latitudes. With a favourable breeze, day after day, the squadron was wafted on, so that it was unnecessary to shift a single sail.

They now began to observe patches of weeds drifting from the west, which increased in size as they advanced. These, together with a white tropical bird which never sleeps on the water, made Columbus hope that he was approaching some island; for, as he had come but three hundred and sixty leagues since leaving the Canary Islands, he supposed the mainland still to be far off.

The breeze was soft and steady, the water smooth. The crews were in high spirits, and every seaman was on the look-out, for a pension of ten thousand maravedis had been promised to him who should first discover land.

Alonzo Pinzon in the Pinta took the lead. On the afternoon of the 13th of September he hailed the Admiral, saying that from the flight of numerous birds and the appearance of the northern horizon, he thought there was land in that direction; but Columbus replied that it was merely a deception of the clouds, and would not alter his course.

The following day there were drizzling showers, and two boobies flew on board the Santa Maria, birds which seldom wander more than twenty leagues from land. Sounding, however, no bottom was found. Unwilling to waste the present fair breeze, he resolved, whatever others thought, to keep one bold course until the coast of India was reached.

Notwithstanding, even the favourable breeze began to frighten the seamen, who imagined that the wind in those regions might always blow from the east, and if so, would prevent their return to Spain.

Not long after the wind shifted to the south-west, and restored their courage, proving to them that the wind did not always prevail from the east. Several small birds also visited the ships, singing as they perched on the rigging, thus showing that they were not exhausted by their flight. Again the squadron passed among numerous patches of seaweed, and the crews, ever ready to take alarm, having heard that ships were sometimes frozen in by ice, fancied that they might be fixed in the same manner, until they were caught by the nipping hand of winter.

Then they took it into their heads that the water was growing shoaler, and expressed their fears that they might run on some sand-banks and be lost. Then a whale was seen, which creature Columbus assured them never went far from land. Notwithstanding, they became uneasy at the calmness of the weather, declaring that as the prevailing winds were from the east, and had not power to disturb the torpid stillness of the ocean, there was the risk of perishing amidst stagnant and shoreless waters, and being prevented by contrary winds from ever returning to Spain.

Next a swell got up, which showed that their terrors caused by the calm were imaginary. Notwithstanding this, and the favourable signs which increased his confidence, he feared that after all, breaking into mutiny, they would compel him to return.

The sailors fancied that their ships were too weak for so long a voyage, and held secret consultations, exciting each other’s discontent. They had gone farther than any one before had done. Who could blame them, should they, consulting their safety, turn back?

Columbus, though aware of the mutinous disposition of his crew, maintained a serene and steady countenance, using gentle words with some, stimulating the pride and avarice of others, and threatening the refractory.

On the 25th of September the wind again became favourable, and the squadron resumed its westerly course. Pinzon now, on examining the chart, supposed that they must be approaching Cipango. Columbus desired to have it returned, and it was thrown on board at the end of a line.

While Columbus and his pilot were studying it, they heard a shout, and looking up saw Pinzon standing at the stern of the Pinta, crying, “Land! land! Señor, I claim my reward!”

There was indeed an appearance of land to the south-west. Columbus and the other officers threw themselves on their knees, and returned thanks to God. The seamen, mounting the rigging, strained their eyes in the direction pointed out, but the morning light put an end to their hopes.

Again with dejected hearts they proceeded, the sea, as before, tranquil, the breeze propitious, and the weather mild and delightful. In a day or two more weeds were seen floating from east to west, but no birds were visible. The people again expressed their fears that they had passed between two islands; but after the lapse of another day the ships were visited by numberless birds, and various indications of land became more numerous. Full of hope, the seamen ascended the rigging, and were continually crying out that they saw land.

Columbus put a stop to these false alarms, declaring that should any one assert that they saw land, and it was not discovered within three days, he should forfeit all claim to the reward.

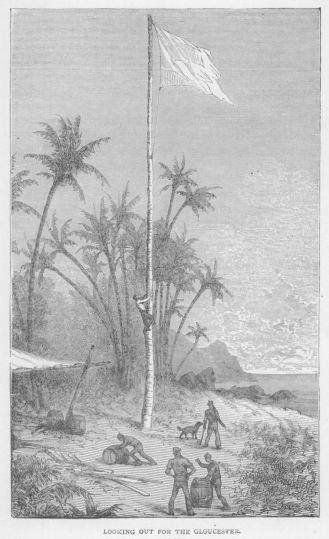

Pinzon now proposed that they should steer south-west, but Columbus persisted in keeping a westerly course. On the 7th of October, at sunrise, several of the Admiral’s crew fancied that they saw land; the Nina pressing forward, a flag was run up at her masthead, and a gun was fired,—the preconcerted signal for land.

The captain and his crew were mistaken notwithstanding. The clouds which had deceived them melted away. The crews again became dejected. But once more flocks of field birds were seen flying through the air to the south-west, and Columbus, having already run the distance at the termination of which he had expected to find the island of Cipango, fancied he might have missed it. He therefore altered his course to the south-west.

As the ships advanced the signs of land increased: a heron, a pelican, and a duck were seen bound in the same direction. Branches of trees, and grass, fresh and green, were observed. The crews, however, believing these to be mere delusions for leading them on to destruction, insisted on abandoning the voyage.

Columbus sternly resisted their importunities, and the

All gloom and mutiny now gave way to sanguine expectations, and Columbus promised a doublet of velvet, in addition to the pension to be given by the sovereign, to whosoever should first see the longed-for shore.

As he walked the high poop of his ship at night, his eye continually ranging along the horizon, he thought he saw a light glimmering at a great distance. Fearing that his hopes might deceive him, he successively called up two of his officers. They both saw it, apparently proceeding from a torch in the bark of a fisherman, or held in the hand of some person on shore, borne up as he walked.

So uncertain were these gleams that few attached any importance to them. The ships continued their course until two in the morning, when Rodrigo de Triana, a seaman on board the Pinta, descried land at two leagues ahead. A gun was fired from the Santa Maria, to give the joyful news. When all doubt on the subject was banished the ships lay to.

Who can picture the thoughts and feelings of Columbus, as he walked the deck, impatiently waiting for dawn, which was to show him clearly the long-sought-for land, with, as he hoped, its spicy groves, its glittering temples, its gilded cities, and all the splendour of Oriental civilisation!

As the dawn of the 12th of October, 1492, increased, Columbus first observed one of the outlying islands of the New World. It was several leagues in extent, level, and covered with trees, and populated, for the naked inhabitants were seen running from all parts to the shore, and gazing with astonishment at the ships. The anchors being dropped, the boats manned, he, richly attired in scarlet and holding the royal standard, accompanied by the Pinzons in their own boats, approached the shore.

On landing he threw himself on his knees, and kissing the earth, returned thanks to God, the rest following his example. He then, drawing his sword, took possession of the island, which he named San Salvador, in the names of the sovereigns of Castile. The crews now thronged round the Admiral, some embracing him, others kissing his hands, expressing their joy; the most mutinous becoming the most enthusiastic and devoted.

The natives, who had at first fled, supposing the ships monsters which had risen from the deep, recovering their fears, now timidly advanced, lost in admiration at the shining armour and splendid dresses of the Spaniards, and their complexions and beards, at once recognising the Admiral as the commander of the strangers.

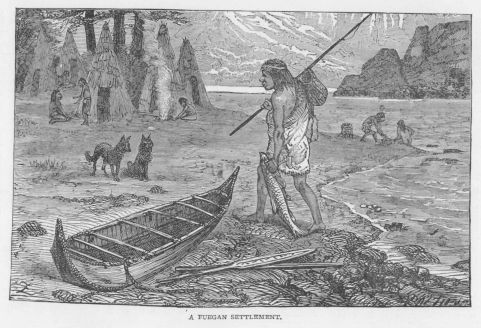

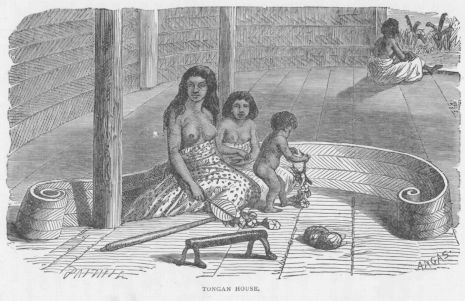

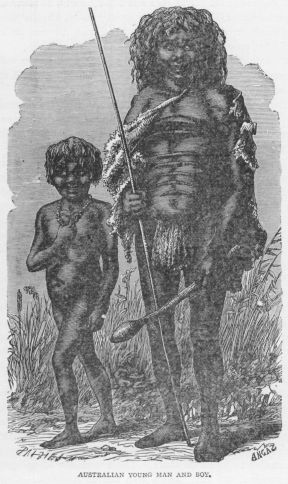

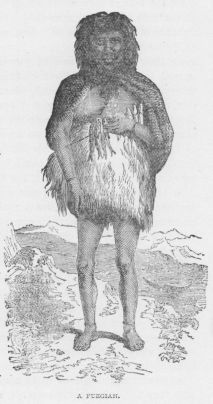

Columbus, pleased with their gentleness, suffered them to scrutinise him, and won them by his benignity. The natives were equally objects of curiosity to the Spaniards. They were naked, painted all over with a variety of colours and designs. Their complexion was tawny, and they were destitute of beards; their hair not crisp, like that of negroes, but straight and coarse; their features were agreeable; their stature moderate and well shaped; their foreheads lofty, and their eyes remarkably fine.

As Columbus supposed that he had landed on an island at the extremity of India, he called the natives Indians, as the inhabitants of the New World have ever since been denominated. Their only arms were lances pointed with the teeth or bones of fishes. There was no iron seen, and so ignorant were the natives of its properties, that one of them took a drawn sword by the edge, not aware that it would cut.

Columbus, to win their confidence, distributed among them coloured caps, hawks’ bells, and glass beads, with which they were highly pleased, allowing the Spaniards unmolested to walk about the groves examining the beautiful trees, the shrubs, fruits, and flowers, all so strange to them.

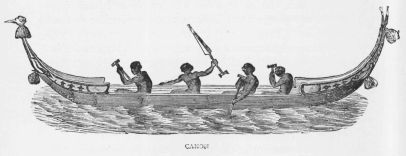

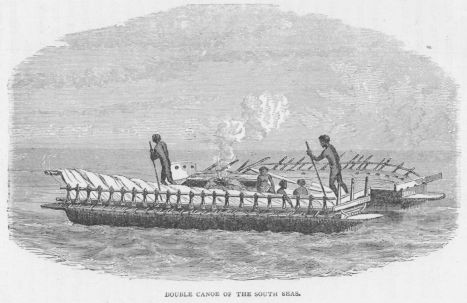

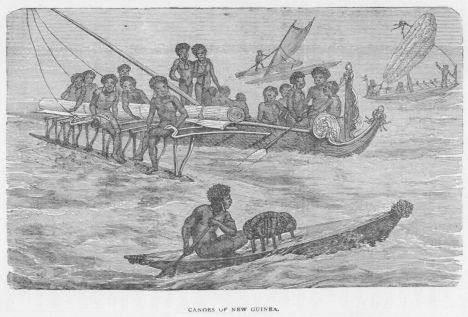

The next morning canoes of all sizes, formed out of single trees, came off, some holding one man, some forty or fifty, who managed them with great dexterity.

They readily accepted toys and trinkets, which, supposing them to be brought from heaven, possessed a supernatural virtue in their eyes. The only things they had to give in return were parrots and balls of cotton-yarn, besides cassava cakes, formed from the flour of a root called yuca, which they cultivated in their fields. The Spaniards, who were eagerly looking out for gold, were delighted to obtain some small ornaments of that metal in exchange for beads and hawks’ bells. As it was a royal monopoly, Columbus forbade any traffic in it, as he did also in cotton, reserving to the crown all trade in it.

Misled by the accounts he had read in Marco Polo’s works, he was from the first persuaded that he had arrived at the islands lying opposite Cathay in the Chinese seas, and that the country to the south, which he understood from the natives abounded in gold, must be the famous island of Cipango.

San Salvador, where he first landed, still retains its name, though called by the English from its shape Cat Island. It is one of the great cluster of the Lucayos or Bahama Islands. Coasting round it in the boats, the Admiral visited various spots, and had friendly intercourse with the natives, to whom he gave glass beads and other trifles.

He landed at another place, where there were six Indian huts surrounded by groves and gardens as beautiful as those of Castile.

At last the sailors, wearied with their exertions, returned to the ships, carrying seven Indians, that they might, by acquiring the Spanish language, serve as interpreters. Taking in a supply of wood and water, the squadron sailed the same evening to the south, where the Admiral expected to discover Cipango. As the Indians told him there were upwards of a hundred islands in the neighbourhood, he was confirmed in his belief that they must be those described by Marco Polo, abounding with gold, silver, drugs, and spices.

Several other islands were visited, but the explorers looked in vain for bracelets and anklets of gold. One day, just as the ships were about to make sail, one of the San Salvador Indians on board the Nina, plunging overboard, swam to a large canoe which had come near. A boat was sent in chase, but the Indians in their light canoe escaped, and reaching the island fled to the woods. Shortly afterwards a canoe, having on board a single native, coming near, he was captured and brought to Columbus, who, treating him with kindness won his heart; his canoe was also restored to him, and that taken by the Nina was set at liberty.

Soon afterwards, while traversing the channel between two islands, when about midway another Indian in his canoe was overtaken, a string of glass beads round his neck, showing that he had come from San Salvador.

Columbus, admiring his hardihood, had him and his canoe taken on board, when he was treated with great kindness, bread and honey being given him to eat. It was too late to select a spot through the transparent sea for anchoring, and the ship lay to until the morning, while the Indian voyager, with all his effects and loaded with presents, was allowed to depart.

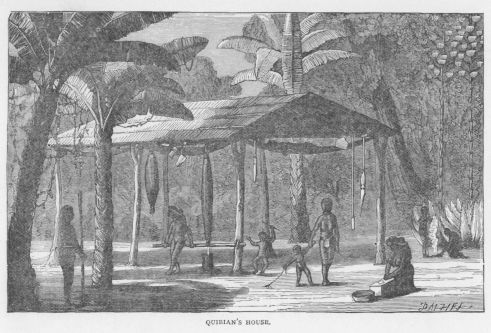

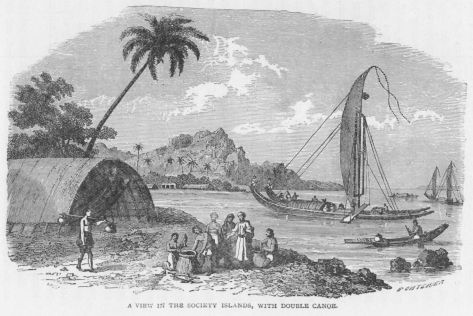

Next day the natives came off, bringing fruits, and roots, and pure water. They were treated in the same way as the former had been. Their huts, which were formed of tall poles and branches neatly interwoven with palm-leaves of a circular form, were visited. They were clean and neat, and generally sheltered under wide-spreading trees. For beds they had nets of cotton extended between two posts, which they called hammocks, a name since generally adopted by seamen.

Columbus, as he sailed round the island, found a magnificent harbour, sufficient to hold a hundred ships. He was delighted with the beauty of the scenery, the shady groves, the fruits, the herbs and flowers,—all differing so greatly from those of Spain. Everywhere the natives received their visitors as superior beings, and gladly conducted them to the coolest springs, and assisted them in rolling their casks to the boats. To the last island visited by Columbus he gave the name of Fernandina. Sailing thence on the 19th of October, he steered in quest of a large island called Saometo, where, misled by his guides, he expected to find the sovereign of the surrounding islands, habited in rich clothes and jewels and gold, possessed of great treasures, a large city, and a gold-mine. Neither were found; but the voyagers were delighted with the balmy air, the beautiful scenery, the graceful trees, the vast flocks of parrots and other birds of gorgeous plumage, and the fish, which rivalled them in the brilliancy of their colours. No animals were seen, with the exception of a dog which never barked, a species of rabbit, and numerous lizards and iguanas.

Columbus was as much misled by his own fervent imagination as by not comprehending the accounts given him by the natives. He proposed that his stay at those islands should depend upon the quantity of gold, spices, precious stones, and other objects of Oriental trade which he should find there. After this he intended to proceed to the mainland of India, which he calculated was within ten days’ sail, and there, after visiting some of its magnificent capitals described by Marco Polo, he would deliver the letters of the sovereigns to the Grand Khan, with whose reply he would return triumphantly to Spain.

Such was his idea when, leaving the Bahamas, he went in quest of the island of Cuba, of which he had been told.

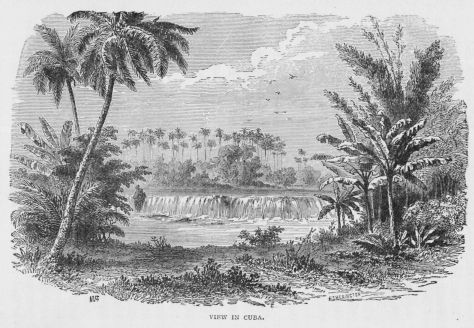

Touching at various islands, having crossed the Bahama bank, he came in sight of Cuba on the morning of the 28th of October. He was struck as he approached by its lofty mountains, its far-stretching headlands, its plains and valleys, and noble rivers.

He anchored in a beautiful stream, the banks overhung with trees. Here landing, he took possession of the island, giving it the name of Juana, in honour of Prince Juan, and the river that of San Salvador. Going on shore in search of the inhabitants, he found only two abandoned huts, containing a few nets, hooks, and harpoons of bone, showing that the owners were mere savages.

Again he was delighted with the scenery, and the vast flights of birds of gorgeous plumage, parrots, woodpeckers, and humming-birds flitting among the trees, and sucking honey from the flowers. He fancied too, from the smell of the woods, that he perceived the fragrance of Oriental spices. He discovered also shells of the kind of oysters which produce pearls.

Having experienced since his arrival soft and genial weather, he concluded that a perpetual serenity reigned over those happy seas. Though the inhabitants had fled, he remarked that their dwellings were better built than those he had hitherto seen, being clean in the extreme; and as he discovered a few rude statues and wooden masks ingeniously carved, he supposed that these signs of civilisation would go on increasing as he advanced towards terra firma. He fancied that the inhabitants had fled, mistaking his armament for one of those scouring expeditions sent by the Grand Khan to make prisoners and slaves. He, however, with the assistance of his Indian friends, succeeded in calming the fears of the natives, who came off in sixteen canoes, bringing cotton-yarn

Again misled by his guides, he was induced to believe that a powerful chief lived in the interior of the country, and two of his officers were therefore dispatched, carrying presents and specimens of spices and drugs, to ascertain whether such productions were to be found there. They were directed also to obtain all the information they could respecting it.

While his envoys were absent he had his ships careened and repaired. During this time reports were brought him of the existence of cinnamon-trees, nutmegs, and rhubarb; and his native friends, when he showed them gold and pearls, declared that there were people in an island called Bohio who wore such things round their necks, arms, and ankles.

The return of the envoys was eagerly looked forward to, but their report when they appeared quickly disabused the Admiral’s mind. After travelling about twelve leagues they arrived at a village of about fifty houses, containing a thousand inhabitants, who had received them with every mark of respect, looking upon them as beings of a superior order. The villagers, however, were as little advanced in civilisation as those on the coast, nor was gold, cinnamon, nor pepper to be found among them, although they said such things existed far off to the south-west.

On their return with some of the inhabitants, the Spaniards were surprised to see them roll up the dried leaves of a plant which they called “tobacco,” and smoke it with a satisfaction which the voyagers could not comprehend, as it appeared to them an unsavoury nauseous indulgence, little dreaming what determined smokers their descendants would become. The envoys described the country as fertile in the extreme, the fields produced pepper, sweet potatoes, maize, pulse, and yuca, while the trees were laden with tempting fruits of delicious flavour. There was also a vast quantity of cotton,—some just growing, some in full growth,—while the houses were stored with it partly wrought into yarn and nets.

Columbus was, by the misapprehension of terms, led into many errors. Bohio, meaning simply “a house,” and therefore signifying a populous island, was frequently applied to Hispaniola. His great object, however, was to reach some civilised country of the East with which he might establish commercial relations, and carry home its Oriental merchandise as a rich trophy of his discovery. Besides Bohio, he had heard of another island called Babique, of which he now sailed in search, hoping that it might prove some civilised island on the coast of Asia. Shortly afterwards he altered his course east-south-east, following back the direction of the coast, and thus did not discover his mistake in supposing Cuba to be a part of terra firma, an error in which he continued to the day of his death.

Some time was spent in cruising about an archipelago of small and beautiful islands, which has since afforded a lurking-place for piratical craft.

In attempting to reach the supposed land of Babique, he met with a contrary gale, which compelled him to put about, when he made signals to the other vessels to do likewise.

The Pinta did not obey him, and when morning dawned was nowhere to be seen. This circumstance disturbed Columbus, who had reason to fear that Pinzon, jealous of his success, intended to prosecute the discovery by himself, or to return to Spain with an account of the success of the enterprise.

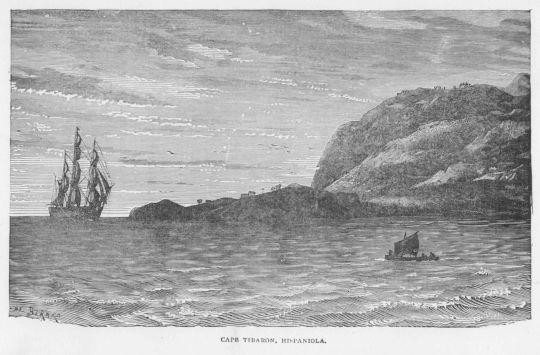

Finding that Pinzon did not rejoin him, he returned to Cuba, and continued for several days sailing along the coast. Again and again he was struck with the magnificence of the scenery and size of the trees, out of a single trunk of which canoes were formed, capable of holding one hundred and fifty people. On the 5th of December he reached the eastern end of Cuba, and then steering large, away from it, he discovered land to the south-east. On approaching, he saw high mountains towering above the horizon, and found that it was an island of great extent, being Hagi or Hispaniola.

Again his native friends exclaimed, “Bohio!”—by which they meant to say that it was thickly populated, though, as he understood the expression, that it abounded with gold. He was struck with the unrivalled beauty of its scenery. On the following day he entered a harbour at the western end, which he called Saint Nicholas. It was deep and spacious, surrounded by trees, many of them loaded with fruit.

Sailing again, he entered another harbour, called Port Concepcion, now known as the Bay of Moustique. Wishing to open an intercourse with the natives, he sent six well-armed men into the interior. The people fled, but the sailors captured a young female who was perfectly unclothed,—a bad omen as to the civilisation of the island,—but an ornament of gold in her nose gave hope that the precious metal might be found there.

The Admiral soothed her terror by presenting her with beads, brass rings,—hawks’ bells, and other trinkets, and sent her on shore clothed, accompanied by several of the crew and three Indian interpreters. She would, however, willingly have remained with the native women she found on board. The party were afraid of venturing to the village, and, having set her at liberty, returned to the ship.

The following morning nine well-armed men, with an interpreter from Cuba, again landed and approached a village containing a thousand houses, but the inhabitants had fled. The interpreter, however, overtook them, and telling them that the strangers had descended from the skies, and went about the world making beautiful presents, they turned back to the number of a thousand, approaching the Spaniards with slow and trembling steps, making signs of profound reverence.

While they were conversing another large party of Indians approached, headed by the husband of the female captive, whom they brought in triumph on their shoulders. The husband expressed his gratitude for the magnificent presents bestowed on his wife.

The Indians, now conducting the Spaniards to their houses, set before them a banquet of cassava bread, fish, roots, and fruits of various kinds. They presented also numbers of tame parrots, freely offering, indeed, whatever they possessed.

Delighted as they were with all they saw, the Spaniards still bitterly complained that they found no signs of riches among the natives. Nature abundantly supplying all they required, they were without even a knowledge of artificial wants, and so unbounded was their hospitality, that they were ready to bestow everything they possessed on their guests. The fertile earth producing all they required, they preferred to live in that Arcadian state of simplicity which poets have delighted to picture. Their fields and gardens were without hedges or divisions of any sort. They were kind to each other, and required no magistrates nor laws to keep them in order. Alas! how soon was this happy state of existence to be destroyed by the cruel, avaricious, and profligate Spaniards. Unlike their pious, high-minded, and sagacious chief, they resembled the bloodhounds they were wont to let loose in chase of their victims.

How different might have been the fate of the islands had such men as the pilgrim fathers or the enlightened Penn been the first to settle among them! The bright light of true Christianity might have beamed on their hearts, with all the advantages of civilisation, and far greater happiness than they had hitherto enjoyed might have been their lot. No blame can be attached to Columbus, no slur can be cast

Chapter Three.

First voyage of Columbus continued—A.D. 1492.

The Tortugas—Returns to Hispaniola—Picks up an Indian in a canoe on the way—The Indian’s report induces a cacique to visit the ships—Friendly intercourse with other caciques—Farther along the coast, an envoy from the great cacique Guacanagari visits the ships—The notary sent to the cacique—His large, clean village—The Spaniards treated as superior beings—Cibao, mistaken for Cipango, heard of—The ship of Columbus wrecked—Guacanagari’s generous behaviour—Terror of the Indians at hearing a cannon discharged—Delighted with hawks’ bells—Stores from the wreck saved—A fort built with the assistance of the natives, and called La Natividad—The cacique’s friendship for Columbus—Abundance of gold obtained—A garrison of thirty men left in the fort, with strict rules for their government—Guacanagari sheds tears at parting with the Admiral—The Nina sails eastward—The Pinta rejoins him—Pinzon excuses himself—His treachery discovered—In consequence of it Columbus resolves to return to Spain—Pinzon’s ill treatment of the natives—Fierce natives met with—First native blood shed—The Indians notwithstanding visit the ship—Columbus steers for Spain—Contrary winds—A fearful storm—The device of Columbus for preserving the knowledge of his discoveries—The Azores reached—Castañeda, Governor of Saint Mary’s—Crew perform a pilgrimage to the Virgin’s shrine—Seized by the Governor—Caravel driven out to sea—Matters settled with Castañeda—Sails—Another tempest—Nearly lost—Enters the Tagus—Courteously received by the King of Portugal—Reaches Palos 15th of March, 1493—Enthusiastic reception at Palos—Pinzon in the Pinta arrives—Dies of shame and grief—Columbus received with due honour by Ferdinand and Isabella—Triumphal entrance into Barcelona—His discovery excites the enterprise of the English.

After a brief stay among the happy and simple-minded natives, the weather becoming favourable, Columbus again attempted to discover the island of Babique. On his way he fell in with an island, to which, on account of the number of turtles seen there, he gave the name of Tortugas. Meeting with contrary winds, he returned to Hispaniola, and on the way fell in with an Indian in a canoe. Having taken the man and his frail barque on board, he treated him kindly and set him on shore at Hispaniola, near a river known as Puerto de Paz.

The Indian gave so favourable a report of the treatment he had received, that a cacique in the neighbourhood, and some of his people, visited the ships. They were handsomer than any yet met with, and of a gentle and peaceable disposition. Several of them wore ornaments of gold, which they readily exchanged for trifles.

Another young cacique shortly afterwards appeared, carried on a litter borne by four men, and attended by two hundred of his subjects. He was received on board, and, Columbus being at dinner, he came down with two of his councillors, who seated themselves at his feet. He merely tasted whatever was given to him, and then sent it to his followers.

Dinner being over, he presented to the Admiral two pieces of gold, and a curiously-worked belt, evidently the wampum still employed by the North American Indians as a token of peace. Columbus, in return, gave him a piece of cloth, several amber beads, coloured shoes, and, showing him a Spanish coin with the heads of the King and Queen, endeavoured to explain to him the power and grandeur of his sovereigns, as well as the standard of the cross; but these apparently failed to have any effect on the mind of the savage chieftain. Columbus also had a large cross erected in the centre of the village, and, from the respect the Indians paid to it, he argued that it would be easy to convert them to Christianity.

Again sailing on the 20th of December, the expedition anchored in the Bay of Acul. Here the inhabitants received them with the greatest frankness. They appeared to have no idea of traffic, but freely gave everything they possessed, though Columbus ordered that articles should be given in exchange for all received.

Several caciques came off, inviting the Spaniards to their villages. Among them came an envoy from an important chief named Guacanagari, ruling over all that part of the island. Having presented a broad belt of wampum and a wooden mask, the eyes, nose, and tongue of which were of gold, he requested that the ships would come off the town where the cacique resided. As this was impossible, owing to a contrary wind, Columbus sent the notary of the squadron, with several attendants. The town was the largest and best built they had yet seen. The cacique received them in a large, clean square, and presented to each a robe of cotton, while the inhabitants brought fruits and provisions of various sorts. The seamen were also received into their houses, and presented with cotton garments and anything they seemed to admire; while the articles given in return were treasured up as sacred relics.

Several caciques had in the meantime visited the ships. They mentioned a region, evidently the interior, called Cibao, which Columbus thought must be a corruption of Cipango, and whose chief he understood had banners of wrought gold, and was probably the magnificent prince mentioned by Marco Polo.

As soon as the wind was fair, Columbus visited the chief, Guacanagari, the coast having been surveyed by boats the previous day. Feeling perfectly secure, although so near the coast, he retired to his cabin. The helmsman handed over his charge to one of the ship’s boys, and failed to notice that breakers were ahead. Suddenly the ship struck; the master and crew rushed on deck. Columbus, calm as usual, ordered the pilot to carry out an anchor astern. Instead of so doing, in his fright, he rowed off to the other caravel, about half a league to windward. Her commander instantly went to the assistance of his chief. The ship had meantime been drifting more and more on the reef, the shock having opened several of her seams. The weather continued fine, or she must at once have gone to pieces.

The Admiral, having gone on board the caravel, sent envoys to Guacanagari, informing him of his intended visit and his disastrous shipwreck. When the cacique, who lived a league and a half off, heard of the misfortune, he shed tears, and sent a fleet of canoes to render assistance. With their help the vessel was unloaded, the chief taking care that none of the effects should be pilfered. Not an article was taken; indeed, the people exhibited the greatest sympathy with their guests, who were treated with the utmost hospitality.

Two days afterwards Guacanagari came on board the Nina to visit the Admiral, and, with tears in his eyes, offered him all he possessed. While he was on board a canoe arrived with pieces of gold, and, on observing his countenance light up, the cacique told him there was a place not far off, among the mountains, where it could be procured in the greatest abundance. He called the place Cibao, which Columbus still confounded with that of Cipango.

Guacanagari, after dining on board, where he exhibited the utmost frankness, invited Columbus to his village. Here he had prepared an abundant banquet, consisting of coneys, fish, roots, and various fruits. He afterwards conducted the Admiral to some beautiful groves, where a thousand natives were collected to perform their national games and dances.

In return, the Admiral sent on board for a Castilian accustomed to the use of the Moorish bow and arrows. The cacique was greatly surprised at the skill with which the Castilian used his weapon, and told him that the Caribs, who made frequent descents on his territory, were also armed with bows and arrows.

Columbus promised his protection, and, to show his host the powerful means at his disposal, ordered a heavy cannon and an arquebus to be discharged. At the report the Indians fell to the ground, as if they had been struck by a thunderbolt. As they saw the shot shivering a tree, they were filled with dismay, until Columbus assured them that these weapons should be turned against their enemies.

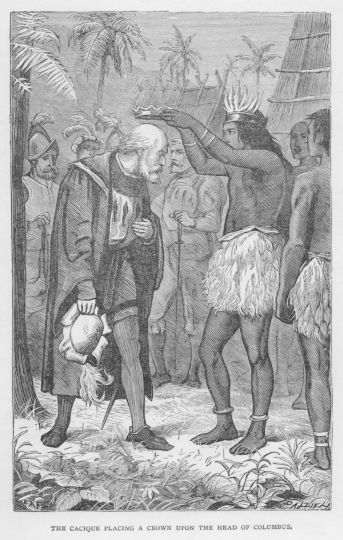

The cacique now presented Columbus with a wooden mask, the eyes, ears, and other parts, of gold; and he also placed a golden crown on his head, and hung plates of gold round his neck. The natives, though willing to receive anything in exchange for gold, were chiefly delighted with the hawks’ bells, dancing and playing a dozen antics as they listened to the sound. An Indian gave even a handful of gold for one of the toys, and then bounded away, fearing that the stranger might repent having parted so cheaply with such an inestimable a treasure. The shipwrecked Spaniards, delighted with their idle life on shore, expressed their wish to remain on the island. This, with the friendly behaviour of the natives, induced Columbus to agree to their proposal. He considered that they might explore the island, learn the language and manners of the natives, and procure by traffic a large amount of gold. He resolved also to build a fortress for their defence, to be armed with the guns saved from the wreck. With his usual promptness he had the work commenced.

When Guacanagari heard that some of the Spaniards were to be left on the island for its defence from the Caribs, he was overjoyed, as were his subjects, who eagerly lent their assistance in building the fortress, little dreaming that they were assisting to place on their necks the galling yoke of slavery.

While the work of the fortress was rapidly going on, Guacanagari treated the Admiral with princely generosity. As Columbus, on one occasion, was landing, the cacique met him, accompanied by five tributary chiefs, each carrying a coronet of gold. On arriving at his house, Guacanagari took

Columbus, by misunderstanding names and descriptions, formed the most magnificent idea of the wealth of the interior of the island, and even in the red pepper which abounded he fancied that he traced Oriental spices. He was thus led to believe that the shipwreck was providential, as, had he sailed away, he should not have heard of its vast wealth. What in some spirits would have awakened a grasping and sordid cupidity to accumulate, immediately filled his vivid imagination with plans of magnificent expenditure.

To the fortress, which was of some size, and sufficiently strong to repulse a naked and unwarlike people, Columbus gave the name of La Navidad, in memory of having escaped shipwreck on Christmas Day. He considered it very likely to prove most useful in keeping the garrison themselves in order, and to prevent them wandering about and committing acts of licentiousness among the natives.

Of the numbers who volunteered he selected thirty-nine in all, among whom was a physician, a ship’s carpenter, a cooper, a tailor, and a gunner; the command being given to Diego de Arana, notary and alguazil of the armament, with Pedro Gutierrez and Rodrigo de Escobedo as his lieutenants, directing them to obtain all the information in their power. He charged the garrison to be especially circumspect in their intercourse with the natives,—to treat them with gentleness and justice,—to be highly discreet in their conduct towards the Indian females, and, moreover, not to scatter themselves, or on any account stray beyond the friendly territory of Guacanagari.

On the 2nd of January, 1493, Columbus bade farewell to the generous cacique and his chieftains, commending those he left behind to their care. To impress the Indians with an idea of the warlike prowess of the white man, after a banquet he had given at his house, he ordered them to engage in mock fights with swords, bucklers, crossbows, arquebuses, and cannon.

Guacanagari shed tears as he parted with Columbus, who, returning on board, two days afterwards set sail, the garrison on shore answering the cheers of their comrades who were about to return to their native land. The ship, being towed out of the harbour, they stood to the eastward, but were detained for two days by a contrary wind.

On the 6th, a seaman aloft cried out that he saw the Pinta. The certainty that he was right cheered the heart of the Admiral and his crew. In a short time she approached, and, as the wind was contrary, Columbus put back to a little bay west of Monte Cristo, where he was followed by the Pinta.

Pinzon endeavoured to excuse himself, but Columbus discovered that he had purposely separated, and had gone to Hispaniola, where he had remained trading with the natives; collecting a considerable quantity of gold, the greater part of which he retained, and the rest divided among the men to secure his secret.

Columbus, however, knowing the number of friends the Pinzons had on board, repressed his indignation; but so much was his confidence in his confederates impaired, that, instead of continuing his explorations, as he hoped to have done when he first saw the Pinta, he resolved at once to sail for Spain.

While obtaining wood and water for the voyage at a river flowing into the bay, so much gold was perceived in the sand at its mouth that the name of Rio del Oro, or the Golden River, was given to it. At present it is called the Santiago. Turtles of large size were found here, and, as a proof how so sagacious a man as Columbus might deceive himself, he states that he here saw three mermaids, who were very far from lovely, although they had traces of human countenances. They were undoubtedly manatees or sea-cows.

Putting into the river where Pinzon had been trading, some of the natives complained that he had violently carried off four men and two girls to be sold as slaves in Spain.

Discovering that such was the case, Columbus ordered that they should be restored immediately to their homes, and, giving them numerous presents and clothing, he sent them on shore.

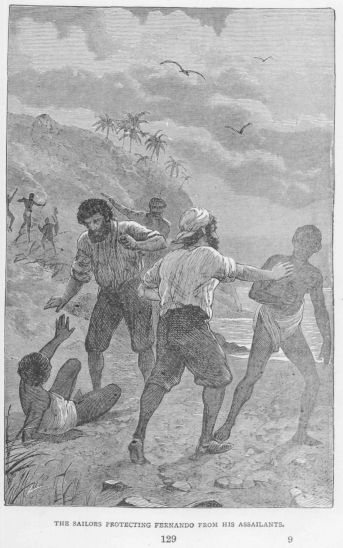

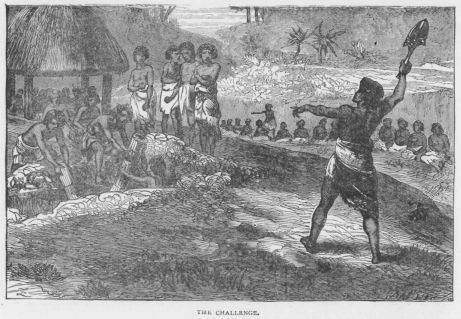

Proceeding on, they anchored in a deep gulf a little way beyond Cape Cabron. The natives were found to be of a ferocious aspect, hideously painted. Their hair was long, tied behind, and decorated with coloured feathers; some were armed with war-clubs; others had bows as long as those used by English archers, with slender reed arrows pointed with bone or the teeth of a fish. Their swords were of palm wood, as hard and heavy as iron, not sharp, but broad, and capable, with one blow, of cleaving through a helmet.

Columbus fancied that they must be Caribs, but an Indian on board assured him that the Caribbean Islands were much farther off. They made no attempt, however, at first, to molest the Spaniards. One of them came on board the Admiral’s ship. Various presents having been given him, he was sent again on shore in one of the boats.

As she approached, upwards of fifty savages, armed with bows, arrows, war-clubs, and javelins, were seen lurking among the trees. The Indian, however, speaking to them, they laid by their arms, and parted with two of their bows to the Spaniards. Suddenly, however, mistrusting their visitors, they rushed back to where they had left their weapons, and returned with cords as if to bind the Spaniards. The latter on this immediately attacked them, wounded two, and put the rest to flight, and would have pursued them had they not been restrained by the commander of the boat.

This was the first time native blood, soon to flow so freely, was shed by the white man in the New World. It greatly grieved Columbus thus to see his efforts to maintain a friendly intercourse frustrated.

Next day, notwithstanding the above occurrence, when a large party went on shore, the cacique who ruled over the neighbourhood came down to meet them, and sent a wampum belt as a token of amity. The cacique, with only three attendants, without fear entered the boat, and was conveyed on board the caravel. Columbus highly appreciated this frank, confiding conduct, and, having placed biscuits and honey and other food before his guests, shown them round the ship, and made them several presents, he sent them back to the land highly gratified. No other interruption occurred to their friendly intercourse. Four young Indians who came on board gave such glowing accounts of the islands to the east, that Columbus prevailed on them to accompany him as guides. He also wished to visit two islands which he fancied to exist,—one inhabited by Amazons, and the other by men; but a favourable breeze springing up for Spain, and observing the gloom in the countenances of the seamen,—knowing as he did also their insubordinate spirit, and the leaky state of the ships, and that, should they founder, his glorious discovery would be lost to the civilised world,—he deemed it wise to steer directly homewards. The favourable breeze, however, soon died away, and for the remainder of the voyage light winds from the eastward prevailed.

The Pinta also sailed badly, her foremast being so defective that it could carry but little sail. In the early part of February, having run to about the thirty-eighth degree of north latitude, they got out of the track of the trade winds, and once more were able to steer a direct course. The pilots, by the changes of their courses, at length got perplexed; but Columbus kept so careful a reckoning that he felt sure of their position. The two principal pilots made out that they were one hundred and fifty leagues nearer Spain than he knew to be the case. He, however, allowed them to remain in their error, that he alone might possess a knowledge of the route to the newly-discovered countries. By his calculation they were not far off from the Azores. On the 12th of February a strong gale with a heavy sea got up, and the next day the wind and swell so increased that Columbus was aware that a heavy tempest was approaching. It soon burst upon them with frightful violence, increasing still more on the 14th, the waves threatening every moment to overwhelm their battered barks. After laying to for three hours they were compelled to scud before the wind. During the darkness of the night the Pinta was lost sight of. The Admiral steered as well as he could to the north-east to approach the coast of Spain, showing lights to the Pinta; but no answering signals were seen, and fears were entertained that she had foundered. The following day the tempest raged as furiously as before on the helpless bark. During the storm the ignorant and superstitious crew cast lots as to who should perform pilgrimages to their respective saints, in which the Admiral, no less superstitious than his men, joined. Two of the lots fell on him. Each man also made his private vow to perform some pilgrimage, or other penitential rite.

The heavens, however, were deaf to their vows. The storm increased, and the crew gave themselves up for lost. The Admiral took the wisest steps to preserve the ship, by ordering that the empty casks should be filled with water, to ballast her better. His mind all the time was a prey to the most painful anxiety. His fear was that the Pinta had already foundered, and that his vessel would also go to the bottom.

An expedient occurred to him at this time by which, though he and his ships should perish, the glory of his achievement might survive to his name, and its advantages be secured to his sovereigns. He wrote on a parchment a brief account of his voyage and discovery; then, having sealed and directed it to the King and Queen, he wrapped it in a waxed cloth, which he placed in the centre of a piece of wax, and, enclosing the whole in a large cask, threw it into the sea. He also enclosed a copy in a similar manner, placing the cask on the poop so that it might float off should the vessel sink.

These precautions somewhat mitigated his anxiety. Towards sunset a streak of clear sky appeared in the west, the sign of finer weather. It came, though the sea ran so high that little sail could be carried.

At daybreak on the morning of the 15th the cry of “Land!” was raised. The transports of the crew equalled those exhibited on first beholding the New World. Various conjectures were offered as to what land it was. Some thought it the rock of Cintra, others the island of Madeira, others a portion of Spain. Columbus, however, knew that it was one of the Azores, in possession of the Portuguese.

On the evening of the 17th of February the vessel dropped her anchor off the island of Saint Mary’s, the most southern of the Azores, and at length the great navigator was enabled to enjoy the first moments of sleep he had taken for many a day.

Next morning the inhabitants were astonished, on seeing the battered vessel, that she had been able to live through the gale, which had, with unexampled fury, raged for fifteen days. Three seamen who had landed were persuaded to remain and give an account of their adventures.

After some time the Governor, Juan de Castañeda, who claimed an acquaintance with Columbus, sent off fowls, bread, and various refreshments, apologising for not coming himself, on account of the lateness of the hour.

On the following morning Columbus reminded his people of their vows, to go in procession to the shrine of the Virgin at the first place where they should land. The messengers who had been kept on board were sent to make preparations, and a priest arrived at a small chapel dedicated to the Virgin some little distance off. One-half of the crew then landed and walked in procession, barefooted and in their shirts, to the chapel, while the Admiral waited their return to perform the same ceremony with the remainder.

Scarcely, however, had the first party begun their prayers than they were surrounded by a gang of horse and foot from the village, and made prisoners.

As the hermitage could not be seen from the caravel, not being aware of what had taken place, the Admiral feared that his boat had been wrecked, and accordingly, weighing anchor, he stood in a direction to command a view of the chapel.

He now caught sight of a number of armed horsemen, who, dismounting, entered the boat, and came towards the caravel. He accordingly got ready to give them a warm reception, but they approached in a pacific manner, and Castañeda himself, who was in the boat, asked leave to come on board.

Columbus reproached him for his perfidy, to which he replied that he was only acting in accordance with the orders of his sovereigns, so that Columbus began to fear that a war had broken out between the two countries during his absence. He had no time to ascertain the truth before another heavy gale coming on, he was driven from his anchorage, and compelled to stand out to sea.

For two days the vessel remained in the greatest peril, short-handed as she was, being unable to return to her anchorage at Saint Mary’s.

As soon as she dropped anchor, a notary and two priests came off demanding to see his papers on the part of Castañeda, who had sent them to assure him that if it should be found that he really sailed in the service of the Spanish sovereigns, he would render him every assistance in his power.

The notary and priest were satisfied with his letters of commission, and the following morning the boat and seamen were sent back. From the latter Columbus learnt the cause of Castañeda’s conduct. The inhabitants had told them that the King of Portugal, jealous lest his expedition should interfere with his discoveries in India, had directed his governors of islands and distant ports to seize and detain him wherever he should be met with.

Having been detained two days longer at Saint Mary’s in an endeavour to take in wood and ballast, but being prevented by the heavy surf which broke upon the shore, he set sail on the 24th of February. After a fine run of two days the weather again became tempestuous, and there appeared every probability of the ship foundering.

On the 3rd of March land was descried, and it was with the greatest difficulty that the ship could be kept off the shore. At daylight on the 4th the voyagers found themselves off the rock of Cintra, a few miles from Lisbon. Rather than risk another night at sea, Columbus determined to hazard the chance of falling into the hands of the Portuguese. The ship was accordingly steered in and brought up opposite Rastello, at the mouth of the river Tagus.

The oldest mariners who came off assured Columbus that they had never known so temptestuous a winter, and had been watching his vessel with the greatest anxiety since she had first been seen. He immediately dispatched a courier to the King and Queen of Spain with the tidings of his discovery, and requested permission of the King of Portugal to go up to Lisbon, fearing that the inhabitants of Rastello, when they heard of her rich freight, might be tempted to rob her.

The King of Portugal, who was some distance from the capital, at once invited Columbus to visit him. During the interview which ensued he endeavoured to conceal his vexation at having refused the proposals which had been made him by the navigator.

His Court tried to persuade him that Columbus had visited countries over which, according to the Pope’s bull, he had the right to rule. Some had the baseness to hint that Columbus should be assassinated, and suggested that he should be embroiled in a quarrel, during which the project might be accomplished.

The King, happily, had too much magnanimity to agree to so nefarious a measure. He treated Columbus with the greatest courtesy, and a large party of cavaliers escorted him back to his ship.