« back

ROLLO IN LONDON

BY

JACOB ABBOTT.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY TAGGARD AND THOMPSON

M DCCC LXIV.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854, by

Jacob Abbott,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

STEREOTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY.

RIVERSIDE, CAMBRIDGE:

PRINTED BY H. O. HOUGHTON

Calculations.

"Now, Rollo," said Mr. George, after breakfast Monday morning, "we will go into the city and see St. Paul's this morning. I suppose it is nearly two miles from here," he continued. "We can go down in one of the steamers on the river for sixpence, or we can go in an omnibus for eightpence, or in a cab for a shilling. Which do you vote for?"

"I vote for going on the river," said Rollo.

"Now I think of it," said Mr. George, "I must stop on the way, just below Temple Bar; so we shall have to take a cab."

Temple Bar is an old gateway which stands at the entrance of the city. It was originally a part of the wall that surrounded the city. The rest of the wall has long since been removed; but this gateway was left standing, as an ancient and venerable relic. The principal street leading from the West End to the city passes through it under an archway; and the sidewalks, through smaller [Pg 99]arches, are at the sides. The great gates are still there, and are sometimes shut. The whole building is very much in the way, and it will probably, before long, be pulled down. In America it would be down in a week; but in England there is so much reverence felt for such remains of antiquity that the inconvenience which they produce must become very great before they can be removed.

Mr. George and Rollo took a cab and rode towards the city. Just after passing Temple Bar, Mr. George got out of the cab and went into an office. Rollo got out too, and amused himself walking up and down the sidewalk, looking in at the shop windows, while Mr. George was doing his business.

When Mr. George came out Rollo had got into the cab again, and was just at that moment giving a woman a penny, who stood at the window of the cab on the street side. The woman had a child in her arms.

When Rollo first saw the woman, she came up to the window of the cab—where he had taken his seat after he had looked at the shop windows as much as he pleased—and held up a bunch of violets towards him, as if she wished him to buy them. Rollo shook his head. The woman did not offer the violets again, but looked down [Pg 100]towards her babe with an expression of great sadness in her face, and then looked imploringly again towards Rollo, without, however, speaking a word.

Rollo put his hand in his pocket and took out a penny and gave it to her. The woman said "Thank you," in a faint tone of voice, and went away.

It was just at this moment that Mr. George came out to the cab.

"Rollo," said Mr. George, "did not you know it was wrong to give money to beggars in the streets?"

"Yes," said Rollo; "but this time I could not resist the temptation, she looked so piteously at her poor little baby."

Mr. George said no more, but took his seat, and the cab drove on.

"Uncle George," said Rollo, after a little pause, "I saw some very pretty gold chains in a window near here; there was one just long enough for my watch. Do you think I had better buy it?"

"What was the price of it?" asked Mr. George.

"It was marked one pound fifteen shillings," said Rollo; "that is about eight dollars and a half."

"It must be a very small chain," said Mr. George.

"It was small," said Rollo; "just right for my watch and me."

"Well, I don't know," said Mr. George, in a hesitating tone, as if he were considering whether the purchase would be wise or not. "You have got money enough."

"Yes," said Rollo; "besides my credit on your book, I have got in my pocket two sovereigns and two pennies, and, besides that, your due bill for four shillings."

"Yes," said Mr. George, "I must pay that due bill."

What Rollo meant by a due bill was this: Mr. George was accustomed to keep his general account with Rollo in a book which he carried with him for this purpose, and from time to time he would pay Rollo such sums as he required in sovereigns, charging the amount in the book. It often happened, however, in the course of their travels, that Mr. George would have occasion to borrow some of this money of Rollo for the purpose of making change, or Rollo would borrow small sums of Mr. George. In such cases the borrower would give to the lender what he called a due bill, which was simply a small piece of paper with the sum of money borrowed written upon [Pg 102]it, and the name of the borrower, or his initials, underneath. When Mr. George gave Rollo such a due bill for change which he had borrowed of him, Rollo would keep the due bill in his purse with his money until Mr. George, having received a supply of change, found it convenient to pay it.

The due bill which Rollo referred to in the above conversation was as follows:—

A Misfortune.

The queen's birthday proved to be an unfortunate day for Rollo, for he met with quite a serious misfortune in the evening while he and Mr. George were out looking at the illuminations. The case was this:—

Rollo had formed a plan for going with Mr. George in the evening to the hotel where his father and mother were lodging, to get Jennie to go out with them to see the illuminations. They had learned from their landlady that the best place to see them was along a certain street called Pall Mall, where there were a great many club houses and other public buildings, which were usually illuminated in a very brilliant manner.[F]

It was after eight o'clock when Mr. George and Rollo went out; and as soon as they came into the street at Trafalgar Square, they saw all around them the indications of an extraordinary and general excitement. The streets were full of people; and in every direction, and at different distances from them, they could see lights gleaming in the air, over the roofs of the houses, or shining brightly upon the heads of the crowd in the street below, in some open space, or at some prominent and conspicuous corner. The current seemed to be setting to the west, towards the region of the club houses and palaces. The lights were more brilliant, too, in that direction. So Rollo, taking hold of his uncle's hand and hurrying him along, said,—

"Come, uncle George! This is the way! They are all lighted up! See!"

For a moment Rollo forgot his cousin Jennie; though the direction in which he was going led, in fact, towards the hotel where she was.

The sidewalk soon became so full that it was impossible to go on any faster than the crowd itself was advancing; and at length, when Mr. George and Rollo got fairly into Pall Mall, and were in the midst of a great blaze of illuminations, which were shining with intense splendor all around them, they were for a moment, in passing [Pg 161]round a corner, completely wedged up by the crowd, so that they could scarcely move hand or foot. In this jam Rollo felt a pressure upon his side near the region of his pocket, which reminded him of his purse; and it immediately occurred to him that it was not quite safe to have money about his person in such a crowd, and that it would be better to give it to his uncle George to keep for him until he should get home.

So he put his hand into his pantaloons pocket to take out his purse; but, to his great dismay, he found that it was gone.

"Uncle George!" said he, in a tone of great consternation, "I have lost my wallet!"

"Are you sure?" said Mr. George, quietly.

Mr. George knew very well that four times out of five, when people think they have lost a purse, or a ring, or a pin, or any other valuable, it proves to be a false alarm.

Rollo, without answering his uncle's question, immediately began to feel in all his other pockets as well as he could in the crowd which surrounded him and pressed upon him so closely. His wallet was nowhere to be found.

"How much was there in it?" asked Mr. George.

"Two pounds and two pennies," said Rollo, "and your due bill for four shillings."

"Are you sure you did not leave it at home?" asked Mr. George.

"Yes," said Rollo. "I have not taken it out since this morning. I looked it over this morning and saw all the money, and I have not had it out since."

"Some people think they are sure when they are not," said Mr. George. "I think you will find it when you go home."

Rollo was then anxious to go home at once and ascertain if his purse was there. All his interest in seeing the illumination was entirely gone. Mr. George made no objection to this; and so, turning off into a side street in order to escape from the crowd, they directed their steps, somewhat hurriedly, towards their lodgings.

"I know we shall not find it there," said Rollo, "for I am sure I had it in my pocket."

"It is possible that we may find it," said Mr. George. "Boys deceive themselves very often about being sure of things. It is one of the most difficult things in the world to know when we are sure. You may have left it in your other pocket, or put it in your trunk, or in some drawer."

"No," said Rollo; "I am sure I put it in this pocket. Besides, I think I felt the robber's hand when he took it. I felt something there, at any [Pg 163]rate; and that reminded me of my purse; and I thought it would be best for me to give it to you. But when I went to feel for it, it was gone."

Mr. George had strong hopes, notwithstanding what Rollo said, that the purse would be found at home; but these hopes were destined to be disappointed. They searched every where when they got home; but the purse was nowhere to be found. They looked in the drawers, in the pockets of other clothes, in the trunk, and all about the rooms. Mr. George was at length obliged to give it up, and to admit that the money was really gone.

Philosophy.

Mr. George and Rollo held a long conversation on the subject of the lost money while they were at breakfast the morning after the robbery occurred, in the course of which Mr. George taught our hero a good deal of philosophy in respect to the proper mode of bearing such losses.

Before this conversation, however, Rollo's mind had been somewhat exercised, while he was dressing himself in his own room, with the question, whether or not his father would make up this loss to him, as one occasioned by an accident. You will recollect that the arrangement which Mr. Holiday had made with Mr. George was, that he was to pay Rollo a certain sum for travelling expenses, and that Rollo was to have all that he could save of this amount for spending money. Rollo was to pay all his expenses of every kind out of his allowance, except that, in case of any accident, the extra expense which the occurrence of the [Pg 165]accident should occasion was to be reimbursed to him by his father—or rather by Mr. George, on his father's account.

Now, while Rollo was dressing himself on the morning after his loss, the question arose to his mind, whether this was to be considered as an accident in the sense referred to in the above-named arrangement. He concluded that Mr. George thought it was not.

"Because," said he to himself, "if he had thought that this was a loss which was to come upon father, and not upon me, he would have told me so last night."

When the breakfast had been brought up, and our two travellers were seated at the table eating it, Rollo introduced the conversation by expressing his regret that he had not bought the gold watch chain that he had seen in the Strand.

"How unlucky it was," said he, "that I did not buy that chain, instead of saving the money to have it stolen away from me! I am so sorry that I did not buy it!"

"No," replied Mr. George, "you ought not to be sorry at all. You decided to postpone buying it for good and sufficient reasons of a prudential character. It was very wise for you to decide as you did; and now you ought not to regret it. To wish that you had been guilty of an act of folly, [Pg 166]in order to have saved a sovereign by it, is to put gold before wisdom. But Solomon says, you know, that wisdom is better than gold; yea, than much fine gold."

Rollo laughed.

"Well," said Rollo, "at any rate, I have learned one lesson from it."

"What lesson is that?" said Mr. George.

"Why, to be more careful after this about my money."

"No," replied Mr. George, "I don't think that you have that lesson to learn. I think you are careful enough now, not only of your money, but of all your other property. Indeed, I think you are a very careful boy; and any greater degree of care and concern than you usually exercise about your things would be excessive. The fact is, that in all the pursuits and occupations of life we are exposed to accidents, misfortunes, and losses. The most extreme and constant solicitude and care will never prevent such losses, but will only prevent our enjoying what we do not lose. It is as foolish, therefore, to be too careful as it is not to be careful enough.

"Indeed," continued Mr. George, "I think the best way is for travellers to do as merchants do. They know that it is inevitable that they should meet with some losses in their business; and so [Pg 167]they make a regular allowance for losses in all their calculations."

"How much do they allow?" said Rollo.

"I believe it is usually about five per cent.," said Mr. George. "They calculate that, for every one hundred dollars that they trust out in business, they must lose five. Sometimes small losses come along quite frequently. At other times there will be a long period without any loss, and then some great one will occur; so that, in one way or the other, they are pretty sure in the long run to lose about their regular average. So they make their calculations accordingly; and when the losses come they consider them matters of course, like any of their ordinary expenses."

"That is a good plan," said Rollo.

"I think it is eminently a good plan," said Mr. George, "for travellers. In planning a journey, we ought always to include this item in our calculations. We ought to allow so much for conveyance, so much for hotel bills, and so much for losses, and then calculate on the losses just as much as we do on the payment of the railroad fares and hotel bills. That is the philosophy of it.

"However," continued Mr. George, "though we ought not to allow any loss that we may meet with to make us anxious or over-careful afterwards, still we may sometimes learn something by it. [Pg 168]For instance, I think it is generally not best to take a watch, or money, or any thing else of special value in our pockets when we go out among a crowd."

"Yes," said Rollo; "if I had only thought to have put my purse in my trunk when I went out, it would have been safe."

"No," replied Mr. George; "it would not have been safe—that is, not perfectly safe—even then; for a thief might have crept into the house, and gone into your room, and opened the lock, and got out the money while you were away."

"But the front door is kept locked," said Rollo.

"True," said Mr. George; "that is a general rule, I know; but it might have been left open a few minutes by accident, so that the thief could get in—such things do happen very frequently; or one of the servants of the house might have got the trunk open. So that the money is not absolutely safe if you leave it in the trunk. In fact, I think that in all ordinary cases it is safer for me to carry my money in my pocket than to leave it in my trunk in my room. It is only when we are going among crowds that it is safer to leave it in our rooms; but there is no absolute and perfect safety for it any where."

"I don't see," said Rollo, "how they can possibly [Pg 169]get the money out so from a deep pocket without our knowing it."

"It is very strange," said Mr. George; "but I believe the London pickpockets are the most skilful in the world. Sometimes they go in gangs, and they contrive to make a special pressure in the crowd, in a narrow passage, or at a corner, and then some of them jam against the gentleman they are going to rob, pretending that they are jammed by others behind them, and thus push and squeeze him so hard on every side that he does not feel any little touch about his pocket; or, by the time he does feel and notice it, the purse is gone."

"Yes," said Rollo, "that is exactly the way it was with me.

"But there is one thing I could have done," said Rollo. "If I had put my purse in my inside jacket pocket, and buttoned up the jacket tight, then they could not possibly have got it."

"Yes," said Mr. George, "they have a way of cutting through the cloth with the little sharp point of the knife which they have in a ring on one of their fingers. With this they can cut through the cloth any where if they feel a purse underneath, and take it out without your knowing any thing about it till you get home."

"I declare!" said Rollo. "Then I don't see what I could do."

"No," replied Mr. George, "there is nothing that we can do to guard absolutely against the possibility of losing our property when we are travelling—or in any other case, in fact. There is a certain degree of risk that we must incur, and various losses in one way or another will come. All we have to do is to exercise the right degree of precaution, neither too much nor too little, and then submit good naturedly to whatever comes."

This is the end of the story of Rollo's being robbed, except that, the next morning after the conversation above described was held, Rollo found on his table, when he got up and began to dress himself, a small package folded up in paper, with a little note by the side of it. He opened the note and read as follows:—

Dear Rollo: From the moment that your loss was ascertained, I determined that I would refund the amount to you, under the authority which I received from your father to pay all expenses which you might incur through unexpected casualties. This robbery I consider as coming under [Pg 171]that head; and so I refund you the amount, and have charged it to your father.

I did not tell you what my design was in this respect at once, because I thought I would see how you would bear the loss on the supposition that it was to be your own. I also wished to avail myself of the opportunity to teach you a little of the philosophy of the subject. And now, [Pg 172]inasmuch as, in learning the lesson, you have shown yourself an excellent pupil, and as you also evince a disposition to bear the loss like a man, there is no longer any reason for postponement; and so I replace the amount that was taken from you by a little package which accompanies this note.

THE LOSS MADE GOOD.

THE LOSS MADE GOOD.

On opening the package, which was lying on the table by the side of his note, Rollo found within a new wallet very much like the one which he had lost; and in this wallet were two sovereigns, two pennies, and a new due bill from his uncle George for four shillings.

The Docks.

One day Mr. George told Rollo that before leaving London he wished very much to go and see the London docks and the shipping in them.

"Well," said Rollo, "I'll go. But what are the docks?"

It may seem surprising that Rollo should be so ready to go and see the docks before he knew at all what they were. The truth is, what attracted him was the word shipping. Like other boys of his age, he was always ready to go, no matter where, to see ships, or any thing connected with shipping.

So he first said he was ready to go and see the docks, and then he asked what they were.

"They are immense basins," said Mr. George, "excavated in the heart of the city, for ships to go into when they are loading or unloading."

"I thought the ships staid in the river," said Rollo.

"Part of them," said Mr. George; "but not all. There is not room for all of them in the river; at least there is not room for them at the wharves, along the banks of the river, to load and reload. Accordingly, about fifty years ago, the merchants of London began to form companies for the purpose of excavating docks for them. The place that they chose for the docks was at a little distance from the river, below the city. Their plan was to build sheds and warehouses around the docks, so as to have conveniences for loading and unloading their ships close at hand.

"And I want to go and see some of these docks," added he, in conclusion.

"So do I," said Rollo. "Let us go this very day."

Although Rollo was thus ready, and even eager, to go with his uncle to see the docks, the interest which he felt in them was entirely different from that which his uncle experienced. Mr. George knew something about the construction of the works and the history of them, and he had a far more distinct idea of the immense commerce which centred in them, and of the influence of this commerce on the general welfare of mankind and on the wealth and prosperity of London, than Rollo could be expected to have. He accordingly wished to see them, in order to enjoy the emotions [Pg 175]of grandeur and sublimity which would be awakened in his mind by the thought of their prodigious magnitude as works of artificial construction, and of the widely-extended relation they sustained to the human race, by continually sending out ships to the remote regions of the globe, and receiving cargoes in return from every nation and every clime.

Rollo, on the other hand, thought little of these grand ideas. All that he was interested in was the expectation of seeing the ships and the sailors, and of amusing himself with the scenes and incidents which he hoped to witness in walking along the platforms, and watching the processes of loading and unloading the ships, or of moving them from one place to another in the crowded basins.

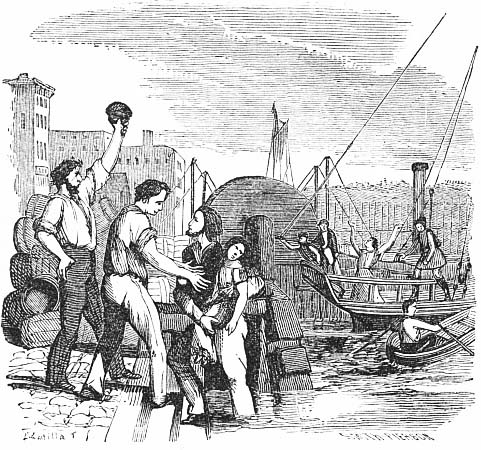

Rollo was not disappointed, when he came to visit the docks, in respect to the interesting and amusing incidents that he expected to see there. He saw a great many such incidents, and one which occurred was quite an uncommon one. A little girl fell from the pier head into the water. The people all ran to the spot, expecting that she would be drowned; but, fortunately, the place where she fell in was near a flight of stone steps, which led down to the water. The people crowded down in great numbers to the steps, to help the child out. The occurrence took place just as the [Pg 176]men from the docks were going home to dinner; and so it happened that there was an unusually large number of people near at the time of the accident.

SAVED.

SAVED.

The place from which the child fell was the corner of the pier head, in the foreground of the picture, where you see the post, just beyond the stone steps.

There is a boat pulling off from the vessel to the rescue of the little girl in the foreground, to the left; but its assistance will not be required.

Now, Rollo's chief interest in going to see the docks was the anticipation of witnessing scenes and incidents of this and other kinds; but Mr. George expected to be most interested in the docks themselves.

The construction of the docks was indeed a work of immense magnitude, and the contrivers of the plan found that there were very great difficulties to be surmounted before it could be carried into effect. It was necessary, of course, that the place to be selected should be pretty low land, and near the river; for if the land was high, the work of excavating the basins would have been so much increased as to render the undertaking impracticable. It was found on examination that all the land that was near the river, and also near the city, and that was in other respects suitable for the purpose, was already occupied with streets and houses. These houses, of course, had all to be bought and demolished, and the materials of them removed entirely from the ground, before the excavations could be begun.

Then, too, some very solid and substantial barrier was required to be constructed between [Pg 178]the excavated basins made and the bank of the river, to prevent the water of the river from bursting in upon the workmen while they were digging. In such a case as this they make what is called a coffer dam, which is a sort of dam, or dike, made by driving piles close together into the ground, in two rows, at a little distance apart, and then filling up the space between them with earth and gravel. By this means the water of the river can be kept out until the digging of the basins is completed.

The first set of docks that was made was called the West India Docks. They were made about the year 1800. Very soon afterwards several others were commenced; and now there are five. The following table gives the names of them, with the number of acres enclosed within the walls of each:—

| Names. | Acres. |

| West India Docks | 295 |

| East India Docks | 32 |

| St. Catharine's Docks | 24 |

| London Docks | 90 |

| Commercial Docks | 49 |

If you wish to form a definite idea of the size of these docks, you must fix your mind upon some pretty large field near where you live, if you live in the country, and ask your father, or [Pg 179]some other man that knows, how many acres there are in it. Then you can compare the field with some one or other of the docks according to the number of acres assigned to it in the above table.

If you live in the city, you must ask the number of acres in some public square. Boston Common contains forty-eight acres.

St. Catharine's Docks contain only twenty-four acres; and yet more than a thousand houses were pulled down to clear away a place for them, and about eleven thousand persons were compelled to remove.

Most of the docks are now entirely surrounded by the streets and houses of the city; so that there is nothing to indicate your approach to them except that you sometimes get glimpses of the masts of the ships rising above the buildings at the end of a street. The docks themselves, and all the platforms and warehouses that pertain to them, are surrounded by a very thick and high wall; so that there is no way of getting in except by passing through great gateways which are made for the purpose on the different sides. These gateways are closed at night.

Mr. George and Rollo, when the time arrived for visiting the docks, held a consultation together [Pg 180]in respect to the mode of going to them from their lodgings at the West End.

Of course the docks, being below the city, were in exactly the opposite direction from where they lived—Northumberland Court. The distance was three or four miles.

"We can go by water," said Mr. George, "on the river, or we can take a cab."

"Or we can go in an omnibus," said Rollo. "Yes, uncle George," he added eagerly, "let us go on the top of an omnibus."

Mr. George was at first a little disinclined to adopt this plan; but Rollo seemed very earnest about it, and finally he consented.

"We can get up very easily," said he; "and when we are up there we can see every thing."

"I am not concerned about our getting up," said Mr. George. "The difficulty is in getting down."

However, Mr. George finally consented to Rollo's proposal; and so, going out into the Strand, they both mounted on the top of an omnibus, and in this way they rode down the Strand and through the heart of London. They were obliged to proceed slowly, so great was the throng of carts, wagons, drays, cabs, coaches, and carriages that encumbered the streets. In about an [Pg 181]hour, however, they were set down a little beyond the Tower.

"Now," said Mr. George, "the question is, whether I can find the way to the dock gates."

"Have you got a ticket?" asked Rollo.

"No," said Mr. George; "I presume a ticket is not necessary."

"I presume it is necessary," said Rollo. "You never can go any where, or get into any thing, in London, without a ticket."

"Well," said Mr. George, "we will see. At any rate, if tickets are required, there must be some way of getting them at the gate."

Mr. George very soon found his way to the entrance of the docks. It was at the end of a short street, the name and position of which he had studied out on the map before leaving home. He took care to be set down by the omnibus near this street; and by this means he found his way very easily to his place of destination.

The entrance was by a great gateway. The gateway was wide open, and trains of carts, and crowds of men,—mechanics, laborers, merchants, clerks, and seamen,—were going and coming through it.

"We need not have concerned ourselves about a ticket," said Mr. George.

"No," said Rollo. "I see."

"The entrance is as public as any street in London," said Mr. George.

So saying, our two travellers walked on and passed within the enclosures.

As soon as they were fairly in, they stopped at the corner of a sort of sidewalk and looked around. The view which was presented to their eyes formed a most extraordinary spectacle. Forests of masts extended in every direction. Near them rose the hulls of great ships, with men going up and down the long plank stairways which led to the decks of them. Here and there were extended long platforms bordering the docks, with immense piles of boxes, barrels, bales, cotton and coffee bags, bars of iron, pigs of lead, and every other species of merchandise heaped up upon them. Carts and drays were going and coming, loaded with goods taken from these piles; while on the other hand the piles themselves were receiving continual additions from the ships, through the new supplies which the seamen and laborers were hoisting out from the hatchways.

Here and there, too, the smoke and the puffing vapor of a steamer were seen, and the clangor of ponderous machinery was heard, giving dignity, as it were, to the bustle.

"So, then, these are the famous London Docks," said Mr. George.

"What a place!" said Rollo.

"I had no idea of the vast extent and magnitude of the works," said Mr. George.

"How many different kinds of flags there are at the masts of the vessels, uncle George!" said Rollo. "Look!"

"What a monstrous work it must have been," said Mr. George, "the digging out by hand of all these immense basins!"

"What did they do with the mud?" asked Rollo.

"They loaded it into scows," said Mr. George, "and floated it off, up or down the river, wherever there were any low places that required to be filled up.

"When, at length, the excavations were finished," continued Mr. George, "they began at the bottom, and laid foundations deep and strong, and then built up very thick and solid walls all along the sides of the basins, up to the level of the top of the ground, and then made streets and quays along the margin, and built the sheds and warehouses, and the work was done."

"But then, how could they get the ships in?" asked Rollo.

"Ah, yes," said Mr. George; "I forgot about that. It was necessary to have passage ways [Pg 184]leading in from the river, with walls and gates, and with drawbridges over them."

"What do they want the drawbridges for?" asked Rollo.

"So that the people that are at work there can go across," said Mr. George. "The people who live along the bank of the river, between the basin and the bank, would of course have occasion to pass to and fro, and they must have a bridge across the outlet of the docks. But then, this bridge, if it were permanent, would be in the way of the ships in passing in and out; and so it must be made a drawbridge.

"Then, besides," continued Mr. George, "they need drawbridges across the passage ways within the docks; for the workmen have to go back and forth continually, in prosecuting the work of loading and unloading the ships and in warping them in and out."

"Yes," said Rollo. "There is a vessel that they are warping in now."

Rollo understood very well what was meant by warping; but as many of the readers of this book may live far from the sea, or may, from other causes, have not had opportunities to learn much about the manœuvring of ships, I ought to explain that this term denotes a mode of moving [Pg 185]vessels for short distances by means of a line, either rope or cable, which is fastened at one end outside the ship, and then is drawn in at the other by the sailors on board. When this operation is performed in a dock, for example, one end of the line is carried forward some little distance towards the direction in which they wish the vessel to go, and is made fast there to a pile, or ring, or post, or some other suitable fixture on the quay, or on board another vessel. The other end of the line, which has remained all the time on board the ship, is now attached to the capstan or the windlass, and the line is drawn in. By this means the vessel is pulled ahead.

Vessels are sometimes warped for short distances up a river, when the wind and current are both against her, so that she cannot proceed in any other way. In this case the outer end of the line is often fastened to a tree.

In the arctic seas a ship is often warped through loose ice, or along narrow and crooked channels of open water, by means of posts set in the larger and more solid floes. When she is drawn up pretty near to one of these posts, the line is taken off and carried forward to another post, which the sailors have, in the mean time, been getting ready upon another floe farther ahead.

Warping is, of course, a very slow way of getting along, and is only practicable for short distances, and is most frequently employed in confined situations, where it would be unsafe to go fast. You would think, too, that this process could only be resorted to near a shore, or a quay, or a great field of ice, where posts could be set to attach the lines to; but this, as will appear presently, is a mistake.

The warping which had attracted Rollo's attention was for the purpose of bringing a ship up alongside of the quay at the place where she was to be unloaded. The ship had just come into the dock.

"She has just come in," said Rollo, "I verily believe. I wish we had been here a little sooner, so as to have seen her come through the drawbridges."

Just at this instant the rope leading from the ship, which had been drawn very tense, was suddenly slacked on board the ship, and the middle of it fell into the water.

"What does that mean?" asked Rollo.

"They are going to fasten it in a new place, I suppose," said Mr. George. "Yes, there's the boat."

There was a boat, with two men in it, just then coming up to the part of the quay where the end [Pg 187]of the line had been fastened. A man on the quay cast off the line, and threw the end down on board the boat. The boatmen, after taking it in, rowed forward to another place, and there fastened it again. As soon as they had fastened it, they called out to the men on board the ship, "Haul away!" and then a moment afterwards the middle of the rope could be seen gradually rising out of the water until it was drawn straight and tense as before; and then the ship began to move on, though very slowly, towards the place where they wished to bring her.

"That's a good way to get her to her place," said Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. George. "I don't know how seamen could manage their vessels in docks and harbors without this process of warping."

"I suppose they can't warp any where but in docks and harbors," said Rollo.

"Why not?" asked Mr. George.

"Because," replied Rollo, "unless there was a quay or a shore close by, they would not have any thing to fasten the line to."

Mr. George then explained to Rollo that they could warp a vessel among the ice in the arctic regions by fastening the line to posts set for the purpose in the great floes.

"O, of course they can do that," said Rollo. [Pg 188]"The ice, in that case, is just the same as a shore; I mean where there is not any shore at all."

"Well," said Mr. George, "they can warp where there is not any shore at all, provided that the water is not too deep. In that case they take a small anchor in a boat, and row forward to the length of the line, and then drop the anchor, and so warp to that."

"Yes," said Rollo; "I see. I did not think of that plan. But when they have brought the vessel up to where the anchor is, what do they do then?"

"Why, in the mean time," said Mr. George, "the sailors in the boat have taken another anchor, and have gone forward with it to a new station; and so, when the ship has come up near enough to the first anchor, they shift the line and then proceed to warp to the second."

Rollo was much interested in these explanations; though, as most other boys would have been in his situation, he was a little disappointed to find himself mistaken in the opinion which he had advanced so confidently, that warping would be impracticable except in the immediate vicinity of the shore. Indeed, it often happens with boys, when they begin to reach what may be called the reasoning age, that, in the conversations which they hold with those older and better informed [Pg 189]than themselves, you can see very plainly that their curiosity and their appetite for knowledge are mingled in a very singular way with the pleasure of maintaining an argument with their interlocutor, and of conquering him in it. It was strikingly so with Rollo on this occasion.

"Yes," said he, after reflecting a moment on what his uncle had said, "yes; I see how they can warp by means of anchors, where there is a bottom which they can take hold of by them; but that is just the same as a shore. It makes no difference whether the line is fastened to an anchor on the bottom, or to a post or a tree on the land. One thing I am sure of, at any rate; and that is, that it would not be possible for them to warp a ship when it is out in the open sea."

"It would certainly seem at first view that they could not," replied Mr. George, quietly; "and yet they can."

"How do they do it?" asked Rollo, much surprised.

"It is not very often that they wish to do it," said Mr. George; "but they can do it, in this way: They have a sort of float, which is made in some respects on the principle of an umbrella. The sailors take one or two of these floats in a boat, with lines from the ship attached to them, and after rowing forward a considerable distance, [Pg 190]they throw them over into the water. The men at the capstan then, on board the ship, heave away, and the lines, in pulling upon the floats, pull them open, and cause them to take hold of the water in such a manner that the ship can be drawn up towards them. Of course the floats do not take hold of the water enough to make them entirely immovable. They are drawn in, in some degree, towards the ship; but the ship is drawn forward much more towards them."

"Yes," said Rollo; "I see that they might do it in that way. But I don't understand why they should have any occasion to warp a ship out in the open sea."

"They do not have occasion to do so often," replied Mr. George. "I have been told, however, that they resort to this method sometimes, in time of war, to get a ship away from an enemy in a calm. Perhaps, too, they might sometimes have occasion to do it in order to get away from an iceberg."

The Emigrants.

While this conversation was going on Mr. George and Rollo had been sauntering slowly along the walk, with warehouses on one side of them, and a roadway for carts and drays on the other, between the walk and the dock; and now all at once Rollo's attention was attracted by the spectacle of a large ship, on the decks of which there appeared a great number of people—men, women, and children.

"What is that?" asked Rollo, suddenly. "What do you suppose all those people are doing on board that ship?"

"That must be an emigrant ship," said Mr. George. "Those are emigrants, I have no doubt, going to America. Let us go on board."

"Will they allow us to go?" asked Rollo, doubtfully.

"O, yes," said Mr. George; "they will not know but that we are emigrants ourselves, or the friends of some of the emigrants. In fact, [Pg 192]we are the friends of some of the emigrants. We are the friends of all of them."

So saying, Mr. George led the way, and Rollo followed up the plankway which led to the deck of the ship. Here a very singular spectacle presented itself to view. The decks were covered with groups of people, all dressed in the most quaint and singular costume, and wearing a very foreign air. They were, in general, natives of the interior provinces of France and Germany, and they were dressed in accordance with the fashions which prevailed in the places from which they severally came.

The men were generally standing or walking about. Some were talking together, others were smoking pipes, and others still were busy with their chests and bundles, rearranging their effects apparently, so as to have easy and convenient access to such as they should require for the voyage. Then there were a great many groups of women and girls seated together on benches, trunks, or camp stools, with little children playing about near them on the deck.

"I am very glad to see this," said Mr. George. "I have very often witnessed the landing of the emigrants in New York at the end of their voyage; and here I have the opportunity of seeing them as they go on board the ship, at the beginning of it."

"I am glad, too," said Rollo. "But look at that old woman!"

Rollo pointed as he said this to an aged woman, whose face, which was of the color of mahogany, was wrinkled in a most extraordinary manner, and who wore a cap of very remarkable shape and dimensions. She had an antique-looking book in her hands, the contents of which she seemed to be conning over with great attention. Mr. George and Rollo looked down upon the pages of the book as they passed, and saw that it was printed in what might be called an ancient black-letter type.

"It is a German book," said Rollo, in a whisper.

"Yes," said Mr. George. "I suppose it is her Bible, or perhaps her Prayer Book."

Near the old woman was a child playing upon the deck. Perhaps it was her grandchild. The child had a small wagon, which she was drawing about the deck. The wagon looked very much worn and soiled by long usage, but in other respects it resembled very much the little wagons that are drawn about by children in America.

"It is just like one of our little wagons," said Rollo.

"Yes," replied Mr. George, "of course it is; [Pg 194]for almost all the little wagons, as well as the other toys, that children get in America, come from Germany."

"Ah!" said Rollo; "I did not think of that."

"Would you ask her to let me see her wagon?" continued Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. George; "that is, if you can ask her in German."

"Don't you suppose she knows English?" asked Rollo.

"No," said Mr. George, "I presume not."

"I mean to try her," said Rollo.

So he extended his hand towards the child; and then, smiling upon her to denote that he was her friend, and also to make what he said appear like an invitation, and not like a command, he pronounced very distinctly the words, "Come here."

The child immediately came towards him with the little wagon.

"There!" said Rollo; "I was pretty sure that she could understand English."

The child did not understand English, however, after all. And yet she understood what Rollo said; for it so happens, by a remarkable coincidence, that the German words for "come here," though spelled differently, sound almost precisely like the English words. Besides, the child knew from Rollo's gesture that he wished her to come to him.

Rollo attempted to talk with the child, but he could make no progress. The child could not understand any thing that he said. Presently a very pleasant-looking woman who was sitting on a trunk near by, and who proved to be the child's mother, shook her head smilingly at Rollo, and said, with a very foreign accent, pointing at the same time to the child, "Not understands English."

Mr. George then held a little conversation with this woman in German. She told him that she was the mother of the child, and that the old woman who was reading near was its grandmother. She had a husband, she said, and two other children. Her husband was on the shore. He had gone into the city to make some purchases for the voyage, and her two other children had gone with him to see what was to be seen.

Mr. George and Rollo, after this, walked about the deck of the ship for some time, looking at the various family groups that were scattered here and there, and holding conversations with many of the people. The persons whom they talked with all looked up with an expression of great animation and pleasure in their countenances when they learned that their visitors were Americans, and seemed much gratified to see them. I suppose they considered them very favorable specimens [Pg 196]of the people of the country which they were going to make their future home.

I am sure that they needed all the kind words and encouraging looks that Mr. George and Rollo bestowed upon them; for it is a very serious and solemn business for a family to bid a final farewell to their native land, and in many instances to the whole circle of their acquaintances and friends, in order to cross the stormy ocean and seek a home in what is to them an entirely new world.

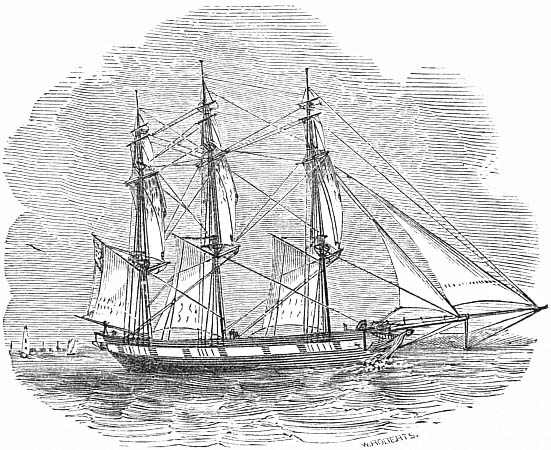

PLEASANT WEATHER.

PLEASANT WEATHER.

Even the voyage itself is greatly to be dreaded by them, on account of the inevitable discomforts and dangers of it. While the ship is lying in the docks, waiting for the appointed day of sailing to arrive, they can pass their time very pleasantly, sitting upon the decks, reading, writing, or sewing; but as soon as the voyage has fairly commenced, all these enjoyments are at once at an end; for even if the wind is fair, and the water is tolerably smooth, they are at first nearly all sick, and are confined to their berths below; so that, even when there are hundreds of people on board, the deck of the ship looks very solitary.

The situation of the poor passengers, too, in their berths below, is very uncomfortable. They are crowded very closely together; the air is confined and unwholesome; and their food is of the coarsest and plainest description. Then, besides, in every such a company there will always be some that are rude and noisy, or otherwise disagreeable in their habits or demeanor; and those who are of a timid and gentle disposition often suffer very severely from the unjust and overbearing treatment which they receive from tyrants whom they can neither resist nor escape from.

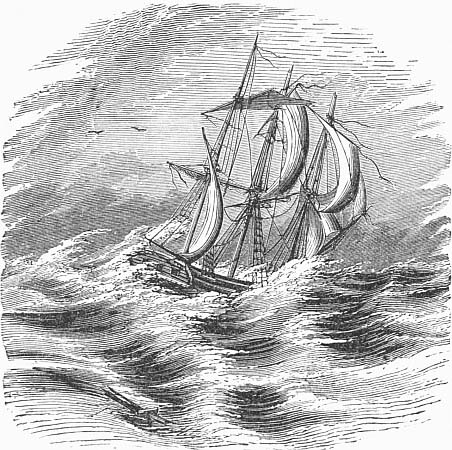

Then, sometimes, when the ship is in mid ocean, there comes on a storm. A storm at sea, attacking [Pg 198]an emigrant ship full of passengers, produces sometimes a frightful amount of misery. Many of the company are dreadfully alarmed, and feel sure that they will all certainly go to the bottom. Their terror is increased by the tremendous roar of the winds, and by the thundering thumps and concussions which the ship encounters from the waves.

THE STORM.

THE STORM.

The consternation is increased when the gale comes on suddenly in a squall, so that there is not time to take the sails in in season. In such a case the sails are often blown away or torn into pieces—the remnants of them, and the ends of the rigging, flapping in the wind with a sound louder than thunder.

Of course, during the continuance of such a storm, the passengers are all confined closely below; for the seas and the spray sweep over the decks at such times with so much violence that even the sailors can scarcely remain there. Then it is almost entirely dark where the passengers have to stay; for in such a storm the deadlights must all be put in, and the hatches shut down and covered, to keep out the sea. Notwithstanding all the precautions, however, that can possibly be taken, the seas will find their way in, and the decks, and the berths, and the beds become dripping wet and very uncomfortable.

Then, again, the violent motion of a ship in a storm makes almost every body sick; and this is another trouble. It is very difficult, too, at such times, for so large a company to get their food. They cannot go to get it; for they cannot walk, or even stand, on account of the pitching and tossing of the ship; and it is equally difficult to bring it to them. The poor children are always [Pg 200]greatly neglected; and the mournful and wearisome sound of their incessant fretting and crying adds very much to the general discomfort and misery.

It often happens, moreover, that dreadful diseases of an infectious and malignant character break out on board these crowded ships, and multitudes sicken and die. Of course, under such circumstances, the sick can receive very few of the attentions that sick persons require, especially when the weather is stormy, and their friends and fellow-passengers, who would have been glad to have assisted them, are disabled themselves. Then, in their dejection and misery, their thoughts revert to the homes they have left. They forget all the sorrows and trials which they endured there, and by the pressure of which they were driven to the determination to leave their native land; and now they mourn bitterly that they were induced to take a step which is to end so disastrously. They think that they would give all that they possess to be once more restored to their former homes.

Thus, during the prevalence of a storm, the emigrant ship is filled sometimes with every species of suffering. There is, however, comparatively very little actual danger, for the ships are very strong, being built expressly for the purpose of [Pg 201]resisting the severest buffetings of the waves; and generally, if there is sea room enough, they ride out these gales in safety. Then, after repairing the damages which their spars and rigging may have sustained, they resume their voyage. If, however, there is not sea room enough for the ship when she is thus caught,—that is, if the storm comes on when she is in such a position that [Pg 202]the wind drives her towards rocks, or shoals, or to a line of coast,—her situation becomes one of great peril. In such cases it is almost impossible to save her from being driven upon the rocks or sands, and there being broken up and beaten to pieces by the waves.

THE WRECK.

THE WRECK.

When driven thus upon a shore, the ship usually strikes at such a distance from it as to make it impossible for the passengers to reach the land. Nor can they long continue to live on board the ship; for, as she strikes the sand or rocks upon the bottom, the waves, which continue to roll in in tremendous surges from the offing, knock her over upon her side, break in upon her decks, and drench her completely in every part, above and below. Those of the passengers who attempt to remain below, or who from any cause cannot get up the stairways, are speedily drowned; while those who reach the deck are almost all soon washed off into the sea. Some lash themselves to the bulwarks or to the masts, and some climb into the rigging to get out of the way of the seas, if, indeed, any of the rigging remains standing; and then, at length, when the sea subsides a little, people put off in surf boats from the shore, to rescue them. In this way, usually, a considerable number are saved.

These and other dreadful dangers attend the [Pg 203]companies of emigrants in their attempts to cross the wide and stormy Atlantic. Still the prospect for themselves and their children of living in peace and plenty in the new world prompts them to come every year in immense numbers. About eight hundred such shiploads as that which Rollo and Mr. George saw in the London Docks arrive in New York alone every year. This makes, on an average, about fifteen ships to arrive there every week. It is only a very small proportion indeed of the number that sail that are wrecked on the passage.

But to return to Mr. George and Rollo.

After remaining on board the emigrant ship until their curiosity was satisfied, our travellers went down the plank again to the quay, and continued their walk. The next thing that attracted Rollo's attention was a great crane, which stood on the quay, near a ship, a short distance before them.

"Ah!" said Rollo; "here is a great crane. Let us go and see what they are hoisting."

So Rollo hastened forward, Mr. George following him, until they came to the crane. Four workmen were employed at it, in turning the wheels by means of two great iron cranks. They were hoisting a very heavy block of white marble out of the vessel.

While Mr. George and Rollo were looking at the crane, a bell began to ring in a little steeple near by; and all the men in every part of the quay and in all the sheds and warehouses immediately stopped working, put on their jackets, and began walking away in throngs towards the gates.

"Ah!" said Mr. George, in a tone of disappointment, "we have got here at twelve o'clock. That was just what I wished to avoid."

"Yes," said Rollo; "they are all going home to dinner."

Rollo, however, soon found that all the men were not going home to dinner, for great numbers of them began to make preparations for dining in the yard. They began to establish themselves in little groups, three or four together, in nooks and corners, under the sheds, wherever they could find the most convenient arrangement of boxes and bales to serve for chairs and tables. When established in these places, they proceeded to open the stores which they had provided for their dinners, the said stores being contained in sundry baskets, pails, and cans, which had been concealed all the morning in various hiding-places among the piles of merchandise, and were now brought forth to furnish the owners with their midday meal.

One of these parties, Rollo found, had a very convenient way of getting ale to drink with their dinner. There was a row of barrels lying on the quay near where they had established themselves to dine; and two of the party went to one of these barrels, and, starting out the bung, they helped themselves to as much ale as they required. They got the ale out of the barrel by means of a long and narrow glass, with a string around the neck of it, and a very thick and heavy bottom. This glass they let down through the bunghole into the barrel, and then drew up the ale with it as you would draw up water with a bucket from a well.

Rollo amused himself as he walked along observing these various dinner parties, wondering, too, all the time, at the throngs of men that were pouring along through all the spaces and passage ways that led towards the gate.[G]

"I did not know that there were so many men at work here," said he.

"Yes," said Mr. George. "When business is brisk, there are about three thousand at work here."

"How did you know?" asked Rollo.

"I read it in the guide book," said Mr. George.

Here Mr. George took his guide book out of his pocket, and began to read from it, as he walked along, the following description:—

"'As you enter the dock, the sight of the forest of masts in the distance, and the tall chimneys vomiting clouds of black smoke, and the many-colored flags flying in the air, has a most peculiar effect; while the sheds, with the monster wheels arching through the roofs, look like the paddle boxes of huge steamers.'"

"Yes," said Rollo; "that is exactly the way it looks."

"'Along the quay,'" continued Mr. George, still reading, "'you see, now men with their faces blue with indigo; and now gaugers, with their long, brass-tipped rules dripping with spirit from the cask they have been probing; then will come a group of flaxen-haired sailors, chattering German; and next a black sailor, with a cotton handkerchief twisted turban-like around his head; presently a blue-smocked butcher, with fresh meat and a bunch of cabbages in a tray on his shoulder; and shortly afterwards a mate, with green paroquets in a wooden cage. Here you will see, sitting on a bench, a sorrowful-looking woman, with new, bright cooking tins at her feet, [Pg 207]telling you she is an emigrant preparing for her voyage. As you pass along the quay the air is pungent with tobacco, or it overpowers you with the fumes of rum; then you are nearly sickened with the smell arising from heaps of hides and huge bins of horns; and shortly afterwards the atmosphere is fragrant with coffee and spice. Nearly every where you meet stacks of cork, or yellow bins of sulphur, or lead-colored copper ore.'"

"It is an excellent description," said Rollo, when Mr. George paused.

Mr. George resumed his reading as follows:—

"'As you enter this warehouse the flooring is sticky, as if it had been newly tarred, with the sugar that has leaked through the casks—— '"

"We won't go there," said Rollo, interrupting.

"'And as you descend into these dark vaults,'" continued Mr. George, "'you see long lines of lights hanging from the black arches, and lamps flitting about midway.'"

"I should like to go there," said Rollo.

"'Here you sniff the fumes of the wine,'" continued Mr. George, "'and there the peculiar fungous smell of dry rot. Then the jumble of sounds, as you pass along the dock, blends in any thing but sweet concord. The sailors are singing [Pg 208]boisterous Ethiopian songs from the Yankee ship just entering; the cooper is hammering at the casks on the quay; the chains of the cranes, loosed of their weight, rattle as they fly up again; the ropes splash in the water; some captain shouts his orders through his hands; a goat bleats from some ship in the basin; and empty casks roll along the stones with a hollow, drum-like sound. Here the heavy-laden ships are down far below the quay, and you descend to them by ladders; whilst in another basin they are high up out of the water, so that their green copper sheathing is almost level with the eye of the passenger; while above his head a long line of bow-sprits stretch far over the quay, and from them hang spars and planks as a gangway to each ship. This immense establishment is worked by from one to three thousand hands, according as the business is either brisk or slack.'"

Here Mr. George shut the book and put it in his pocket.

"It is a very excellent account of it altogether," said Rollo.

"I think so too," said Mr. George.

As our travellers walked slowly along after this, their attention was continually attracted to one object of interest after another, each of which, [Pg 209]after leading to a brief conversation between them, gave way to the next. The talk was accordingly somewhat on this wise:—

"O uncle George!" said Rollo; "look at that monstrous pile of buck horns!"

"Yes," said Mr. George; "it is a monstrous pile indeed. They must be for knife handles."

"What a quantity of them!" said Rollo. "I should think that there would be knife handles enough in the pile for all creation. Where can they get so many horns?"

"I am sure I don't know," said Mr. George.

So they walked on.

Presently they came to an immense heap of bags of coffee. They knew that the bags contained coffee by the kernels that were spread about them all over the ground. Then they passed by long rows of barrels, which seemed to be filled with sugar. Mr. George walked by the side of the barrels, but Rollo jumped up and ran along on the top of them. Then came casks of tobacco, and next bars of iron and steel, and then some monstrous square logs of mahogany.

Mr. George and Rollo walked on in this manner for a quarter of a mile, and at length they came to one of the drawbridges. This drawbridge led over a passage way which formed a communication from one basin of the dock to [Pg 210]another. It was a very long and slender bridge of iron, made to turn on a pivot at one end. There was some machinery connected with it to work it.

"I wish they would come and turn this drawbridge away," said Rollo. "I want to see how it works."

"Perhaps they will after dinner," said Mr. George.

"Let us sit down, then, here somewhere," said Rollo, "and wait."

So Mr. George and Rollo, after crossing the drawbridge, sat down upon some of the fixtures connected with the machinery of the bridge.

From the place where they sat they had a good view of the whole interior of the dock. They could see the shipping, the warehouses, the forests of masts, the piles of merchandise, and the innumerable flags and signals which were flying at the mast heads of the vessels.

"It is a wonderful place," said Rollo; "but I don't understand how they do the business here. Whom do all these goods belong to? and how do they sell them? We have not seen any body here that looks as if he was buying any thing."

"No," said Mr. George. "The merchants don't come here to buy the goods. They buy them by [Pg 211]samples in the city. I will explain to you how they manage the business. The merchants who own ships send them to various parts of the world to buy what grows in the different countries and bring it here. We will take a particular case. Suppose it is coffee, for instance. The merchant never sees the coffee himself, perhaps. The captain or the supercargo reports to him how much there is, and he orders it to be stored in the warehouses here. Then he puts it into the hands of an agent to sell. His agent is called a broker. There are inspectors in the docks, whose business it is to examine the coffee and send specimens of it to the broker's office in the city. It is the same with all the other shiploads that come in. They are examined by inspectors, specimens are taken out and sent to the city, and the goods themselves are stored in the warehouses.

"Now, we will suppose a person wishes to buy some of these goods to make up a cargo. Perhaps it is a man who is going to send a ship to Africa after elephants' tusks, and he wants a great variety of goods to send there to pay the natives for them. He wants them in large quantities, too, enough to make a cargo. So he makes out a list of the articles that he wishes to send, and marks the quantities of each that he will require, and gives the list to the [Pg 212]agent. This agent is a man who is well acquainted with the docks and the brokers, and knows where they keep the specimens. He buys the articles and sends them all on board the ship that is going to Africa, which is perhaps all this time lying close at hand in the docks, ready to receive them. As fast as the goods are delivered on board the African ship, the captain of it gives the agent a receipt for them, and the latter, when he has got all the receipts, sends them to the merchant; and so the merchant knows that the goods are all on board, without ever having seen any of them."

"And then he pays the agent, I suppose, for his trouble," said Rollo.

"Of course," said Mr. George; "but this is better than for him to attempt to do the business himself; for the agent is so familiar with the docks, and with every thing pertaining to them, that he can do it a great deal better than the merchant could, in half the time."

"Yes," said Rollo, "I should think he could."

"Then it makes the business very easy and pleasant for the merchant, I suppose," said Mr. George. "All that he requires is a small office and a few clerks. He sits down at his desk and considers where he will send his ship, when he has one ready for sea, and what cargo he will [Pg 213]send in her; and then there is nothing for him to do about it but to make out an inventory of the articles and send it to the agent at the docks, and the business is all done very regularly for him.

"Only," continued Mr. George, "it is very necessary that he should know how to plan his voyages so as to make them come out well, with a good profit at the end, otherwise he will soon go to ruin."

Mr. George and Rollo sat near the drawbridge talking in this manner for about half an hour. Then the men began to return from their dinner; and very soon afterwards the quays, and slips, and warehouses were all alive again with business and bustle. They then rose and began rambling about here and there, to watch the various operations that were going on. They saw during this ramble a great many curious and wonderful things, too numerous to be specified here. They remained in the docks for more than two hours, and then went home by one of the little steamers on the river.

The Tower and the Tunnel.

The famous Tunnel under the Thames, and the still more famous Tower of London, are very near together, and strangers usually visit both on one and the same excursion.

The Tower, as has already been explained, was originally a sort of fortress, or castle, built on the bank of the river, below the city, to defend it from any enemy that might attempt to come up to it by ships from the sea. The space enclosed by the walls was very large; and as in modern times many new buildings and ranges of buildings have been erected within, with streets and courts between them, the place has now the appearance of being a little town enclosed by walls, and surrounded by a ditch with bridges, and standing in the midst of a large town.

Rollo and Mr. George passed over the ditch that surrounded the Tower by means of a drawbridge. Before they entered the gateway, however, they were conducted to a small building [Pg 215]which stood near it, where they obtained a ticket to view the Tower, and where, also, they were required to leave their umbrella. This room was a sort of refreshment room; and as they were told that they must wait here a few minutes till a party was formed, they occupied the time by taking a luncheon. Their luncheon consisted of a ham and veal pie, and a good drink for each of ginger beer.

At length, several other people having come in, a portly-looking man, dressed in a very happy uniform, and wearing on his head a black velvet hat adorned with a sort of wreath made of blue and white ribbons, took them in charge to lead them about the Tower.

This man belonged to a body that is called the Yeomen of the Guard. The dress which he wore was their uniform. He wore various badges and decorations besides his uniform. One of them was a medal that was given to him in honor of his having been a soldier at the battle of Waterloo.

Under the charge of this guide, the party, which consisted now of eight or ten persons, began to make the tour. They passed through various little courts and streets, which were sometimes bordered by ranges of buildings, and sometimes by castellated walls, with sentinels on duty, marching slowly back and forth along the parapet.

At length their happy-looking guide led the party through a door which opened into a very long and narrow hall, on one side of which there was arranged a row of effigies of horses, splendidly caparisoned, and mounted with the figures of the kings of England upon them in polished armor of steel. The happy trappings of the horses, and the glittering splendor of the breast-plates, and greaves, and helmets, and swords of the men, gave to the whole spectacle a very splendid effect. The guide walked along slowly in front of this row of effigies, informing the party as he went along of the names of the various monarchs who were represented, and describing the kind of armor which they severally wore.

The armor, of course, varied very much in its character and fashion, according to the age in which the monarch who wore it lived; and it was very interesting, in walking down the hall, to see how military fashions had changed from century to century, as shown by the successive changes in the accoutrements which were observed in passing along the line of kings.

There were many suits of armor that were quite small, having been made for the English princes when they were boys. Rollo amused himself by imagining how he should look in one of [Pg 217]these suits of armor, and he wished very much that he could have an opportunity of trying them on. In one place there was a battery of nine beautiful little cannons made of brass, each about two feet long, and just about large enough in caliber for a boy to fire. These cannons, which were all beautifully ornamented with bas reliefs on the outside, and were mounted on splendid little carriages, were presented to Charles II. when he was a boy; and I suppose that he and his playmates often fired them. There were a great many other strange and curious implements of war that have now gone wholly out of fashion. There were all kinds of matchlocks, and guns, and pistols, of the most uncouth and curious shapes; and shot of every kind—chain shot, and grape shot, and saw shot; and there were bows and arrows, and swords and halberds, and spears and cutlasses, and every other kind of weapon. These arms were arranged on the walls in magnificent great stars, or were stacked up in various ornamental forms about pillars or under arches; and they were so numerous that Rollo could not stop to look at half of them.

After this the yeoman of the guard led his party to a great many other curious places. He showed them the room where the crowns and sceptres of the English kings and queens, and all the great [Pg 218]diamonds and jewels of state, were kept. These treasures were placed on a stand in an immense iron cage, so that people assembled in the room around the cage could look in and see the things, but they could not reach them to touch them.

They were also taken to see various prison rooms and dungeons where state prisoners were kept; and also blocks and axes, the implements by which several great prisoners celebrated in history had been beheaded. They saw in particular the block and the axe which were used at the execution of Anne Boleyn and of Lady Jane Grey; and all the party looked very earnestly at the marks which the edge of the axe had made in the wood when the blows were given.

The party walked about in the various buildings, and courts, and streets of the Tower for nearly two hours; and then, bidding the yeoman good by, they all went away.

"Now," said Rollo, as soon as they had got out of the gate, "which is the way to the Tunnel?"

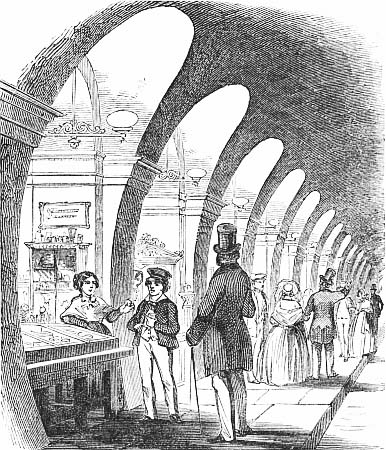

The Tunnel is a subterranean passage under the Thames, made at a place where it was impossible to have a bridge, on account of the shipping. They expected, when they made the Tunnel, that it would be used a great deal by persons wishing to cross the river. But it is found, on trial, that almost every body who wishes to go [Pg 219]across the river at that place prefers to go in a boat rather than go down into the Tunnel. The reason is, that the Tunnel is so far below the bed of the river that you have to go down a long series of flights of stairs before you get to the entrance to it; and then, after going across, you have to come up just as many stairs before you get into the street again. This is found to be so troublesome and fatiguing that almost every one who has occasion to go across the river prefers to cross it by a ferry boat on the surface of the water; and scarcely any one goes into the Tunnel except those who wish to visit it out of curiosity.

The stairs that lead down to the passage under the river wind around the sides of an immense well, or shaft, made at the entrance of it. When Mr. George and Rollo reached the bottom of these stairs they heard loud sounds of music, and saw a brilliant light at the entrance to the Tunnel. On going in, they saw that the Tunnel itself was double, as it consisted of two vaulted passage ways, with a row of piers and arches between them. One of these passage ways was closed up; the other was open, and was lighted brilliantly with gas all the way through. But what most attracted Rollo's attention was, that the spaces between the piers all along the Tunnel were occupied [Pg 220]with little shops, each one having a man, a woman, or a child to attend it. As Mr. George and Rollo walked along, those people all asked them to stop and buy something at their shops. [Pg 221]There were pictures of all kinds, and little boxes, and views of the Tunnel, with magnifying glasses to make them look real, and needle cases, and work boxes, and knickknacks of all kinds for people to buy and carry home as souvenirs, or to show to their friends and say that they bought them in the Tunnel.

SHOPPING IN THE TUNNEL.

SHOPPING IN THE TUNNEL.

Besides these things that were for sale, there were various objects of interest and curiosity, such as electric machines where people might take shocks, and scales where they might be weighed, and refreshment rooms that were formed in the passage way that was not used for travel; and in one place there was a little ball room arranged there, where a party might, if they chose, stop and have a dance.

Rollo and Mr. George walked through the Tunnel, and then came back again. As they came back, Rollo stopped at one of the shops and bought a pretty little round box, which he said would do for a wafer box, and would also serve as a souvenir of his visit to the place.

Mr. George and Rollo concluded, after ascending again to the light of day, that they would go home by water; so they went out to the end of a long floating pier, which was built, as it happened, exactly opposite the entrance to the Tunnel. They sat down on a bench by a little toll [Pg 222]house there, to wait for a steamer going up the river.

"It must have been just about under here," said Rollo, "that I bought my little wafer box in the Tunnel."

"Yes," said Mr. George; "just about."

In a few minutes a steamer came along and took them in. She immediately set off again; and, after passing under all the London bridges and stopping on the way at various landings, she set them down at Hungerford stairs, and they went to their lodgings.

Mr. George and Rollo had various other adventures in London which there is not space to describe in this volume. Rollo did not, however, have time to visit all the places that he wished to see; for, before he had executed half the plans which he and his uncle George had projected, he received a sudden summons to set out, with his father, and mother, and Jennie, for Edinburgh.

FOOTNOTES:

[A] Whenever shillings or sixpences are mentioned in this book, English coin is meant. As a general rule, each English denomination is of double the value of the corresponding American one. Thus the English penny is a coin as large as a silver dollar, and it is worth two of the American pennies. The shilling is of the value of a quarter of a dollar; and a sixpence is equal to a New York shilling.

[B] See frontispiece.

[C] Such a body of ecclesiastics is called a chapter.

[D] The reader will recollect, from the description of Westminster Abbey, that the central part of the body of the church is called the nave, and that the parts of each side of the nave, beyond the ranges of columns that border it on the north and on the south, are called the aisles, and that the aisles are not so high usually as the nave. The long, vacant space which our party was now traversing was directly over the south aisle. They were coming towards the spectator, in the view of the church represented in the engraving. You see two towers in the front of the building shown in the engraving. The one on the right hand is on the south, and is called the clock tower. The other tower, which is on the north, is called the belfry. The party were coming along over the south aisle and south transept towards this south tower. If you read this explanation attentively, comparing it with the engraving, and compare the rest of the description with the engraving, you will be able to follow the party exactly through the whole of their ascent.

[E] The works of this clock are on such a scale that the pendulum is fourteen feet long, and the weight at the end weighs more than one hundred pounds. The minute hand is eight feet long, and weighs seventy-five pounds.

[F] These club houses are very large and splendid mansions belonging to associations of gentlemen called clubs. Some of the clubs contain more than a thousand members. The houses are fitted up in the most luxurious manner, with reading rooms, libraries, dining rooms, apartments for conversation, and for all sorts of games, and every thing else requisite to make them agreeable places of resort for the members. The annual expenditure in many of them is from thirty to fifty thousand dollars.

[G] It was while these workmen were going out in this way from the yard that the incident of the little girl falling into the dock occurred, as has been already related.