« back

Contents

| I | THE HOME IN ALSACE | 1 |

| II | AN APPARITION | 5 |

| III | TOM'S STORY | 12 |

| IV | THE OLD WINE VAT | 22 |

| V | THE VOICE FROM THE DISTANCE | 32 |

| VI | PRISONERS AGAIN | 38 |

| VII | WHERE THERE'S A WILL—— | 42 |

| VIII | THE HOME FIRE NO LONGER BURNS | 51 |

| IX | FLIGHT | 58 |

| X | THE SOLDIER'S PAPERS | 64 |

| XI | THE SCOUT THROUGH ALSACE | 72 |

| XII | THE DANCE WITH DEATH | 79 |

| XIII | THE PRIZE SAUSAGE | 84 |

| XIV | A RISKY DECISION | 90 |

| XV | HE WHO HAS EYES TO SEE | 97 |

| XVI | THE WEAVER OF MERNON | 103 |

| XVII | THE CLOUDS GATHER | 112 |

| XVIII | IN THE RHINE | 118 |

| XIX | TOM LOSES HIS FIRST CONFLICT WITH THE ENEMY | 124 |

| XX | A NEW DANGER | 131 |

| XXI | COMPANY | 137 |

| XXII | BREAKFAST WITHOUT FOOD CARDS | 141 |

| XXIII | THE CATSKILL VOLCANO IN ERUPTION | 145 |

| XXIV | MILITARY ETIQUETTE | 155 |

| XXV | TOM IN WONDERLAND | 162 |

| XXVI | MAGIC | 167 |

| XXVII | NONNENMATTWEIHER | 174 |

| XXVIII | AN INVESTMENT | 180 |

| XXIX | CAMOUFLAGE | 184 |

| XXX | THE SPIRIT OF FRANCE | 190 |

| XXXI | THE END OF THE TRAIL | 196 |

TOM SLADE

WITH THE BOYS OVER THERE

CHAPTER I

THE HOME IN ALSACE

In the southwestern corner of the domains of Kaiser Bill, in a fair district to which he has no more right than a highwayman has to his victim's wallet, there is a quaint old house built of gray stone and covered with a clinging vine.

In the good old days when Alsace was a part of France the old house stood there and was the scene of joy and plenty. In these evil days when Alsace belongs to Kaiser Bill, it stands there, its dim arbor and pretty, flower-laden trellises in strange contrast to the lumbering army wagons and ugly, threatening artillery which pass along the quiet road.

And if the prayers of its rightful owners are answered, it will still stand there in the happy days to come when fair Alsace shall be a part of France2 again and Kaiser Bill and all his clanking claptrap are gone from it forever.

The village in which this pleasant homestead stands is close up under the boundary of Rhenish Bavaria, or Germany proper (or improper), and in the happy days when Alsace was a part of France it had been known as Leteur, after the French family which for generations had lived in the old gray house.

But long before Kaiser Bill knocked down Rheims Cathedral and black-jacked Belgium and sank the Lusitania, he changed the name of this old French village to Dundgardt, showing that even then he believed in Frightfulness; for that is what it amounted to when he changed Leteur to Dundgardt.

But he could not very well change the old family name, even if he could change the names of towns and villages in his stolen province, and old Pierre Leteur and his wife and daughter lived in the old house under the Prussian menace, and managed the vineyard and talked French on the sly.

On a certain fair evening old Pierre and his wife and daughter sat in the arbor and chatted in the language which they loved. The old man had lost an arm in the fighting when his beloved Alsace was3 lost to France and he had come back here still young but crippled and broken-hearted, to live under the Germans because this was the home of his people. He had found the old house and the vineyard devastated.

After a while he married an Alsatian girl very much younger than himself, and their son and daughter had grown up, German subjects it is true, but hating their German masters and loving the old French Alsace of which their father so often told them.

While Florette was still a mere child she committed the heinous crime of singing the Marseillaise. The watchful Prussian authorities learned of this and a couple of Prussian soldiers came after her, for she must answer to the Kaiser for this terrible act of sedition.

Her brother Armand, then a boy of sixteen, had shouted "Vive la France!" in the very faces of the grim soldiers and had struck one of them with all his young strength.

In that blow spoke gallant, indomitable France!

For this act Armand might have been shot, but, being young and agile and the German soldiers being fat and clumsy, he effected a flank move and disappeared before they could lay hands on him and4 it was many a long day before ever his parents heard from him again.

At last there came a letter from far-off America, telling of his flight across the mountains into France and of his working his passage to the United States. How this letter got through the Prussian censorship against all French Alsatians, it would be hard to say. But it was the first and last word from him that had ever reached the blighted home.

After a while the storm cloud of the great war burst and then the prospect of hearing from Armand became more hopeless as the British navy threw its mighty arm across the ocean highway. And old Pierre, because he was a French veteran, was watched more suspiciously than ever.

Florette was nearly twenty now, and Armand must be twenty-three or four, and they were talking of him on this quiet, balmy night, as they sat together in the arbor. They spoke in low tones, for to talk in French was dangerous, they were already under the cloud of suspicion, and the very trees in the neighborhood of a Frenchman's home seemed to have ears....

CHAPTER II

AN APPARITION

"But how could we hear from him now, Florette, any better than before?" the old man asked.

"America is our friend now," the girl answered, "and so good things must happen."

"Indeed, great things will happen, dear Florette," her father laughed, "and our beloved Alsace will be restored and you shall sing the Marseillaise again. Vive l'Amerique! She has come to us at last!"

"Sh-h-h," warned Madame Leteur, looking about; "because America has joined us is no reason we should not be careful. See how our neighbor Le Farge fared for speaking in the village but yesterday. It is glorious news, but we must be careful."

"What did neighbor Le Farge say, mamma?"

"Sh-h-h. The news of it is not allowed. He said that some one told him that when the American General Pershing came to France, he stood by the grave of Lafayette and said, 'Lafayette, we are here.'"6

"Ah, Lafayette, yes!" said the old man, his voice shaking with pride.

"But we must not even know there is a great army of Americans here. We must know nothing. We must be blind and deaf," said Madame Leteur, looking about her apprehensively.

"America will bring us many good things, my sweet Florette," said her father more cautiously, "and she will bring triumph to our gallant France. But we must have patience. How can she send us letters from Armand, my dear? How can she send letters to Germany, her enemy?"

"Then we shall never hear of him till the war is over?" the girl sighed. "Oh, it is my fault he went away! It was my heedless song and I cannot forgive myself."

"The Marseillaise is not a heedless song, Florette," said old Pierre, "and when our brave boy struck the Prussian beast——"

"Sh-h-h," whispered Madame Leteur quickly.

"There is no one," said the old man, peering cautiously into the bushes; "when he struck the Prussian beast, it was only what his father's son must do. Come, cheer up! Think of those noble words of America's general, 'Lafayette, we are here.' If we have not letters from our son, still America7 has come to us. Is not this enough? She will strike the Prussian beast——"

"Sh-h-h!"

"There is no one, I tell you. She will strike the Prussian beast with her mighty arm harder than our poor noble boy could do with his young hand. Is it not so?"

The girl looked wistfully into the dusk. "I thought we would hear from him when we had the great news from America."

"That is because you are a silly child, my sweet Florette, and think that America is a magician. We must be patient. We do not even know all that her great president said. We are fed with lies——"

"Sh-h-h!"

"And how can we hear from Armand, my dear, when the Prussians do not even let us know what America's president said? All will be well in good time."

"He is dead," said the girl, uncomforted. "I have had a dream that he is dead. And it is I that killed him."

"This is a silly child," said old Pierre.

"America is full of Prussians—spies," said the girl, "and they have his name on a list. They have killed him. They are murderers!"8

"Sh-h-h," warned her mother again.

"Yes, they are murderers," said old Pierre, "but this is a silly child to talk so. We have borne much silently. Can we not be a little patient now?"

"I hate them!" sobbed the girl, abandoning all caution. "They drove him away and we will see him no more,—my brother—Armand!"

"Hush, my daughter," her mother pleaded. "Listen! I heard a footstep. They are spying and have heard."

For a moment neither spoke and there was no sound but the girl's quick breaths as she tried to control herself. Then there was a slight rustling in the shrubbery and they waited in breathless suspense.

"I knew it," whispered Madame; "we are always watched. Now it has come."

Still they waited, fearfully. Another sound, and old Pierre rose, pushed his rustic chair from him and stood with a fine, soldierly air, waiting. His wife was trembling pitiably and Florette, her eyes wide with grief and terror, watched the dark bushes like a frightened animal.

Suddenly the leaves parted and they saw a strange disheveled figure. For a moment it paused, uncertain, then looked stealthily about and emerged9 into the open. The stranger was hatless and barefoot and his whole appearance was that of exhaustion and fright. When he spoke it was in a strange language and spasmodically as if he had been running hard.

"Leteur?" he asked, looking from one to the other; "the name—Leteur? I can't speak French," he added, somewhat bewildered and clutching an upright of the arbor.

"What do you wish here?" old Pierre demanded in French, never relaxing his military air.

The stranger leaned wearily against the arbor, panting, and even in the dusk they could see that he was young and very ragged, and with the whiteness of fear and apprehension in his face and his staring eyes.

"You German? French?" he panted.

"We are French," said Florette, rising. "I can speak ze Anglaise a leetle."

"You are not German?" the visitor repeated as if relieved.

"Only we are Zherman subjects, yess. Our name ees Leteur."

"I am—American. My name—is Tom Slade. I escaped from the prison across there. My—my pal escaped with me——"10

The girl looked pityingly at him and shook her head while her parents listened curiously. "We are sorry," she said, "so sorry; but you were not wise to escape. We cannot shelter you. We are suspect already."

"I have brought you news of Armand," said Tom. "I can't—can't talk. We ran——Here, take this. He—he gave it to me—on the ship."

He handed Florette a little iron button, which she took with a trembling hand, watching him as he clutched the arbor post.

"From Armand? You know heem?" she asked, amazed. "You are American?"

"He's American, too," said Tom, "and he's with General Pershing in France. We're goin' to join him if you'll help us."

For a moment the girl stared straight at him, then turning to her father she poured out such a volley of French as would have staggered the grim authorities of poor Alsace. What she said the fugitive could not imagine, but presently old Pierre stepped forward and, throwing his one arm about the neck of the young American, kissed him several times with great fervor.

Tom Slade was not used to being kissed by anybody and he was greatly abashed. However, it11 might have been worse. What would he ever have done if the girl who spoke English in such a hesitating, pretty way had taken it into her head to kiss him?

CHAPTER III

TOM'S STORY

"You needn't be afraid," said Tom; "we didn't leave any tracks; we came across the fields—all the way from the crossroads down there. We crawled along the fence. There ain't any tracks. I looked out for that."

Pausing in suspense, yet encouraged by their expectant silence, he spoke to some one behind him in the bushes and there emerged a young fellow quite as ragged as himself.

"It's all right," said Tom confidently, and apparently in great relief. "It's them."

"You must come inside ze house," whispered Florette fearfully. "It is not safe to talk here."

"There isn't any one following us," said Tom's companion reassuringly. "If we can just get some old clothes and some grub we'll be all right."

"Zere is much danger," said the girl, unconvinced. "We are always watched. But you are friends to Armand. We must help you."13

She led the way into the house and into a simply furnished room lighted by a single lamp and as she cautiously shut the heavy wooden blinds and lowered the light, the two fugitives looked eagerly at the first signs of home life which they had seen in many a long day.

It was in vain that the two Americans declined the wine which old Pierre insisted upon their drinking.

"You will drink zhust a leetle—yess?" said the girl prettily. "It is make in our own veenyard."

So the boys sipped a little of the wine and found it grateful to their weary bodies and overwrought nerves.

"Now you can tell us—of Armand," she said eagerly.

Often during Tom's simple story she stole to the window and, opening the blind slightly, looked fearfully along the dark, quiet road. The very atmosphere of the room seemed charged with nervous apprehension and every sound of the breeze without startled the tense nerves of the little party.

Old Pierre and his wife, though quite unable to understand, listened keenly to every word uttered by the strangers, interrupting their daughter continually to make her translate this or that sentence.14

"There ain't so much need to worry," said Tom, with a kind of dogged self-confidence that relieved Florette not a little. "I wouldn't of headed for here if I hadn't known I could do it without leaving any trace, 'cause I wouldn't want to get you into trouble."

Florette looked intently at the square, dull face before her with its big mouth and its suggestion of a frown. His shock of hair, always rebellious, was now in utter disorder. He was barefoot and his clothes were in that condition which only the neglect and squalor of a German prison camp can produce. But in his gaunt face there shone a look of determination and a something which seemed to encourage the girl to believe in him.

"Are zey all like you—ze Americans?" she asked.

"Some of 'em are taller than me," he answered literally, "but I got a good chest expansion. This feller's name is Archer. He belongs on a farm in New York."

She glanced at Archer and saw a round, red, merry face, still wearing that happy-go-lucky look which there is no mistaking. His skin was camouflaged by a generous coat of tan and those two strategic hills, his cheeks, had not been reduced by the assaults of hunger. There was, moreover, a15 look of mischief in his eyes, bespeaking a jaunty acceptance of whatever peril and adventure might befall and when he spoke he rolled his R's and screwed up his mouth accordingly.

"Maybe you've heard of the Catskills," said Tom. "That's where he lives."

"My dad's got a big apple orrcharrd therre," added Archer.

Florette Leteur had not heard of the Catskills, but she had heard a good deal about the Americans lately and she looked from one to the other of this hapless pair, who seemed almost to have dropped from the clouds.

"You have been not wise to escape," she said sympathetically. "Ze Prussians, zey are sure to catch you.—Tell me more of my bruzzer."

"The Prussians ain't so smarrt," said Archer. "They're good at some things, but when it comes to tracking and trailing and all that, they're no good. You neverr hearrd of any famous Gerrman scouts. They're clumsy. They couldn't stalk a mud turrtle."

"You are not afraid of zem?"

"Surre, we ain't. Didn't we just put one overr on 'em?"

"We looped our trail," explained Tom to the puzzled girl. "If they're after us at all they probably16 went north on a blind trail. We monkeyed the trees all the way through this woods near here."

"He means we didn't touch the ground," explained Archer.

"We made seven footprints getting across the road to the fence and then we washed 'em away by chucking sticks. And, anyway, we crossed the road backwards so they'd think we were going the other way. There ain't much danger—not tonight, anyway."

Again the girl looked from one to the other and then explained to her father as best she could.

"You are wonderful," she said simply. "We shall win ze war now."

"I was working as a mess boy on a transport," said Tom; "we brought over about five thousand soldiers. That's how I got acquainted with Frenchy—I mean Armand——"

"Yes!" she cried, and at the mention of Armand old Pierre could scarcely keep his seat.

"He came with some soldiers from Illinois. That's out west. He was good-natured and all the soldiers jollied him. But he always said he didn't mind that because they were all going to fight together to get Alsace back. Jollying means making fun of somebody—kind of," Tom added.17

"Oh, zat iss what he say?" Florette cried. "Zat iss my brother—Armand—yess!"

She explained to her parents and then advanced upon Tom, who retreated to his second line of defence behind a chair to save himself from the awful peril of a grateful caress.

"He told me all about how your father fought in the Franco-Prussian War," Tom went on, "and he gave me this button and he said it was made from a cannon they used and——"

"Ah, yess, I know!" Florette exclaimed delightedly.

"He said if I should ever happen to be in Alsace all I'd have to do would be to show it to any French people and they'd help me. He said it was a kind of—a kind of a vow all the French people had—that the Germans didn't know anything about. And 'specially families that had men in the Franco-Prussian War. He told me how he escaped, too, and got to America, and about how he hit the German soldier that came to arrest you for singing the Marseillaise."

The girl's face colored with anger, and yet with pride.

"Mostly what we came here for," Tom added in his expressionless way, "was to get some food and18 get rested before we start again. We're going through Switzerland to join the Americans—and if you'll wait a little while you can sing the Marseillaise all you want."

Something in his look and manner as he sat there, uncouth and forlorn, sent a thrill through her.

"Zey are all like you?" she repeated. "Ze Americans?"

"Your brother and I got to be pretty good friends," said Tom simply; "he talked just like you. When we got to a French port—I ain't allowed to tell you the name of it—but when we got there he went away on the train with all the other soldiers, and he waved his hand to me and said he was going to win Alsace back. I liked him and I liked the way he talked. He got excited, like——"

"Ah, yess—my bruzzer!"

"So now he's with General Pershing. It seemed funny not to see him after that. I thought about him a lot. When he talked it made me feel more patriotic and proud, like."

"Yess, yess," she urged, the tears standing in her eyes.

"Sometimes you sort of get to like a feller and you don't know why. He would always get so excited, sort of, when he talked about France or Uncle Sam19 that he'd throw his cigarette away. He wasted a lot of 'em. He said everybody's got two countries, his own and France."

"Ah, yess," she exclaimed.

"Even if I didn't care anything about the war," Tom went on in his dull way, "I'd want to see France get Alsace back just on account of him."

Florette sat gazing at him, her eyes brimming.

"And you come to Zhermany, how?"

"After we started back the ship I worked on got torpedoed and I was picked up by a submarine. I never saw the inside of one before. So that's how I got to Germany. They took me there and put me in the prison camp at Slopsgotten—that ain't the way to say it, but——"

"You've got to sneeze it," interrupted Archer.

"Yes, I know," she urged eagerly, "and zen——"

"And then when I found out that it was just across the border from Alsace I happened to think about having that button, and I thought if I could escape maybe the French people would help me if I showed it to 'em like Frenchy said."

"Oh, yess, zey will! But we must be careful," said Florette.

"It was funny how I met Archer there," said Tom. "We used to know each other in New York. He20 had even more adventures than I did getting there."

"And you escaped?"

"Yop."

"We put one over on 'em," said Archer. "It was his idea (indicating Tom). They let us have some chemical stuff to fix the pump engine with and we melted the barbed wire with it and made a place to crawl out through. I got a piece of the barbed wirre for a sooveneerr. Maybe you'd like to have it," Archer added, fumbling in his pockets.

Florette, smiling and crying all at once, still sat looking wonderingly from one to the other of this adventurous, ragged pair.

"Those Germans ain't so smart," said Archer.

The girl only shook her head and explained to her parents. Then she turned to Tom.

"My father wants to know if zey are all like you in America. Yess?"

"He used to be a Boy Scout," said Archer. "Did you everr hearr of them?"

But Florette only shook her head again and stared. Ever since the war began she had lived under the shadow of the big prison camp. Many of her friends and townspeople, Alsatians loyal still to France, were held there among the growing horde21 of foreigners. Never had she heard of any one escaping. If two American boys could melt the wires and walk out, what would happen next?

And one of them had blithely announced that these mighty invincible Prussians "couldn't even trail a mud turtle." She wondered what they meant by "looping our trail."

CHAPTER IV

THE OLD WINE VAT

"We thought maybe you'd let us stay here tonight and tomorrow," said Tom after the scanty meal which the depleted larder yielded, "and tomorrow night we'll start out south; 'cause we don't want to be traveling in the daytime. Maybe you could give us some clothes so it'll change our looks. It's less than a hundred miles to Basel——"

"My pappa say you could nevaire cross ze frontier. Zere are wires—electric——"

"Electric wirres are ourr middle name," said Archer. "We eat 'em."

"We ain't scared of anything except the daylight," said Tom. "Archy can talk some German and I got Frenchy's—Armand's—button to show to French people. When we once get into Switzerland we'll be all right."

He waited while the girl engaged in an animated talk with her parents. Then old Pierre patted the23 two boys affectionately on the shoulder while Florette explained.

"It iss not for our sake only, it iss for yours. You cannot stay in ziss house. It iss not safe. You aire wonderful, zee how you escape, and to bring us news of our Armand! We must help you. But if zey get you zen we do not help you. Iss it so? Here every day ze Prussians come. You see? Zey do not follow you—you are what you say—too clevaire? But still zey come."

Tom listened, his heart in his throat at the thought of being turned out of this home where he had hoped for shelter.

"We are already suspect," Florette explained. "My pappa, he fought for France—long ago. But so zey hate him. My name zey get—how old——All zeze zings zey write down—everyzing. Zey come for me soon. I sang ze Marseillaise—you know?"

"Yes," said Tom, "but that was years ago."

"But we are suspect. Zey have write it all down. Nossing zey forget. Zey take me to work—out of Alsace. Maybe to ze great Krupps. I haf' to work in ze fields in Prussia maybe. You see? Ven zey come I must go. Tonight, maybe. Tomorrow. Maybe not yet——"24

She struggled to master her emotion and continued. "Ziss is—what you call—blackleest house. You see? So you will hide where I take you. It iss bad, but we cannot help. I give you food and tomorrow in ze night I bring you clothes. Zese I must look for—Armand's. You see? Come."

They rose with her and as she stood there almost overcome with grief and shame and the strain of long suspense and apprehension, yet thinking only of their safety, the sadness of her position and her impending fate went to Tom's heart.

Old Pierre embraced the boys affectionately with his one arm, seeming to confirm all his daughter had said.

"My pappa say it is best you stay not here in ziss house. I will show you where Armand used to hide so long ago when we play," she smiled through her tears. "If zey come and find you——"

"I understand," said Tom. "They couldn't blame it to you."

"You see? Yess."

To Archer, who understood a few odds and ends of German old Pierre managed to explain in that language his sorrow and humiliation at their poor welcome.

All five then went into an old-fashioned kitchen25 with walls of naked masonry and a great chimney, and from a cupboard Florette and her mother filled a basket with such cold viands as were on hand. This, and a pail of water the boys carried, and after another affectionate farewell from Pierre and his wife, they followed the girl cautiously and silently out into the darkness.

Tom Slade had already felt the fangs of the German beast and he did not need any one to tell him that the loathsome thing was without conscience or honor, but as he watched the slender form of Armand's young sister hurrying on ahead of them and thought of all she had borne and must yet bear and of the black fear that must be always in her young heart, his sympathy for her and for this stricken home was very great.

He had not fully comprehended her meaning, but he understood that she and her parents were haunted by an ever-present dread, and that even in their apprehension it hurt them to skimp their hospitality or suffer any shadow to be cast on a stranger's welcome.

Florette led the way along a narrow board path running back from the house, through an endless maze of vine-covered arbor, which completely roofed all the grounds adjacent to the house. Tom,26 accustomed only to the small American grape arbor, was amazed at the extent of this vineyard.

"Reminds you of an elevated railroad, don't it," said Archer.

On the rickety uprights (for the arbor like everything else on the old place was going to ruin under the alien blight) large baskets hung here and there. At intervals the structure sagged so that they had to stoop to pass under it, and here and there it was broken or uncovered and they caught glimpses of the sky.

They went over a little hillock and, still beneath the arbor, came upon a place where the vines had fallen away from the ramshackle trellis and formed a spreading mass upon the ground.

"You see?" whispered the girl in her pretty way. "Here Armand he climb. Here he hide to drop ze grapes down my neck—so. Bad boy! So zen it break—crash! He tumbled down. Ah—my pappa so angry. We must nevaire climb on ze trellis. You see? Here I sit and laugh—so much—when he tumble down!"

She smiled and for a moment seemed all happiness, but Tom Slade heard a sigh following close upon the smile. He did not know what to say so he simply said in his blunt way:27

"I guess you had good times together."

"Now I will zhow you," she said, stooping to pull away the heavy tangle of vine.

Tom and Archer helped her and to their surprise there was revealed a trap-door about six feet in diameter with gigantic rusty hinges.

"Ziss is ze cave—you see?" she said, stooping to lift the door. Tom bent but she held him back. "Wait, I will tell you. Zen you can open it." For a moment pleasant recollections seemed to have the upper hand, and there was about her a touch of that buoyancy which had made her brother so attractive to sober Tom.

"Wait—zhest till I tell you. When I come back from ze school in England I have read ze story about 'Kidnap.' You know?"

"It's by Stevenson; I read it," said Archer.

"You know ze cave vere ze Scotch man live? So ziss is our cave. Now you lift."

The door did not stir at first and Florette, laughing softly, raised the big L band which bent over the top and lay in a rusted padlock eye.

"Now."

The boys raised the heavy door, to which many strands of the vine clung, and Florette placed a stick to hold it up at an angle. Peering within by28 the light of a match, they saw the interior of what appeared to be a mammoth hogshead from which emanated a stale, but pungent odor. It was, perhaps, seven feet in depth and the same in diameter and the bottom was covered with straw.

"It is ze vat—ze wine vat," whispered Florette, amused at their surprise. "Here we keep ze wine zat will cost so much.—But no more.—We make no wine ziss year," she sighed. "Ziss makes ze fine flavor—ze earth all around. You see?"

"It's a dandy place to hide," said Archer.

"So here you will stay and you will be safe. Tomorrow in ze night I shall bring you more food and some clothes. I am so sorry——"

"There ain't anything to be sorry about," said Tom. "There's lots of room in there—more than there is in a bivouac tent. And it'll be comfortable on that straw, that's one sure thing. If you knew the kind of place we slept in up there in the prison you'd say this was all right. We'll stay here and rest all day tomorrow and after you bring us the things at night we'll sneak out and hike it along."

"I will not dare to come in ze daytime," said Florette, "but after it is dark, zen I will come. You must have ze cover almost shut and I will pull ze vines over it."29

"We'll tend to that," said Tom.

"We'll camouflage it, all right," Archer added.

For a moment she lingered as if thinking if there were anything more she might do for their comfort. Then against her protest, Tom accompanied her part way back and they paused for a moment under the thickly covered trellis, for she would not let him approach the house.

"I'm sorry we made you so much trouble," he said; "it's only because we want to get to where we can fight for you."

"Oh, yess, I know," she answered sadly. "My pappa, it break his heart because he cannot make you ze true welcome. But you do not know. We are—how you say—persecute—all ze time. Zey own Alsace, but zey do not love Alsace. It is like—it is like ze stepfather—you see?" she added, her voice breaking. "So zey have always treat us."

For a few seconds Tom stood, awkward and uncomfortable; then clumsily he reached out his hand and took hers.

"You don't mean they'll take you like they took the people from Belgium, do you?" he asked.

"Ziss is worse zan Belgium," Florette sobbed. "Zere ze people can escape to England."

"Where would they send you?" Tom asked.30

"Maybe far north into Prussia. Maybe still in Alsace. All ze familees zey will separate so zey shall meex wiz ze Zhermans." Florette suddenly grasped his hand. "I am glad I see you. So now I can see all ze Americans come—hoondreds——

"Tomorrow in ze night I will bring you ze clothes," she whispered, "and more food, and zen you will be rested——"

"I feel sorry for you," Tom blurted out with simple honesty, "and I got to thank you. Both of us have—that's one sure thing. You're worse off than we are—and it makes me feel mean, like. But maybe it won't be so bad. And, gee, I'll look forward to seeing you tomorrow night, too."

"I will bring ze sings, surely," she said earnestly.

"It isn't—it isn't only for that," he mumbled, "it's because I'll kind of look forward to seeing you anyway."

For another moment she lingered and in the stillness of night and the thickly roofed arbor he could hear her breath coming short and quick, as she tried to stifle her emotion.

"Is—is it a sound?" she whispered in sudden terror.

"No, it's only because you're scared," said Tom.

He stood looking after her as she hurried away31 under the ramshackle trellis until her slender figure was lost in the darkness.

"It'll make me fight harder, anyway," he said to himself; "it'll help me to get to France 'cause—'cause I got to, and if you got to do a thing—you can...."

CHAPTER V

THE VOICE FROM THE DISTANCE

"My idea," said Archer, when Tom returned, "is to break that stick about in half and prop the doorr just wide enough open so's we can crawl in. Then we can spread the vines all overr the top just like it was beforre and overr the opening, too. What d'ye say?"

"That's all right," said Tom, "and we can leave it a little open tonight. In the morning we'll drop it and be on the safe side."

"Maybe we'd betterr drop it tonight and be on the safe side," said Archer. "S'pose we should fall asleep."

"We'll take turns sleeping," said Tom decisively. "We can't afford to take any chances."

"You can bet I'm going to get a sooveneerr of this place, anyway," said Archer, tugging at a rusty nail.

"Never you mind about souvenirs," Tom said; "let's get this door camouflaged."33

"I could swap that nail for a jack-knife back home," said Archer regretfully. "A nail right fresh from Alsace!"

But he gave it up and together they pulled the tangled vine this way and that, until the door and the opening beneath were well covered. Then they crawled in and while Archer reached up and held the door, Tom broke the stick so that the opening was reduced to the inch or two necessary for ventilation. Reaching out, they pulled the vine over this crack until they felt certain that no vestige of door or opening could be seen from without, and this done they sat down upon the straw, their backs against the walls of the vat, enjoying the first real comfort and freedom from anxiety which they had known since their escape from the prison camp.

"I guess we're safe herre forr tonight, anyway," said Archer, "but believe me, I think we've got some job on our hands getting out of this country. It's going to be no churrch sociable——"

"We got this far," said Tom, "and by tomorrow night we ought to have a good plan doped out. We got nothing to do all day tomorrow but think about it."

"Gee, I feel sorry for these people," said Archer; "they'rre surre up against it. Makes me feel as if I'd34 like to have one good whack at Kaiser Bill——"

"Well, don't talk so loud and we'll get a whack at him, all right."

"I'd like to get his old double-jointed moustache for a sooveneerr."

"There you go again," said Tom.

Now that the excitement was over, they realized how tired they were and indeed the strain upon their nerves, added to their bodily fatigue, had brought them almost to the point of exhaustion.

"I'm all in," said Archer wearily.

"All right, go to sleep," said Tom, "and after a while if you don't wake up I'll wake you. One of us has got to stay awake and listen. We can't afford to take any chances."

Archibald Archer needed no urging and in a minute he was sprawled upon the straw, dead to the world. The daylight was glinting cheerily through the interstices of tangled vine over the opening when he awoke with the heedless yawns which he might have given in his own beloved Catskills.

"Don't make a noise," said Tom quickly, by way of caution. "We're in the wine vat in Leteur's vineyard in Alsace, remember." It took Archer a moment to realize where they were. They ate an early breakfast, finding the simple odds and ends35 grateful enough, and then Tom took his turn at a nap.

Throughout most of that day they sat with their knees drawn up, leaning against the inside of the great vat, talking in hushed tones of their plans. There was nothing else they could do in the half darkness and the slow hours dragged themselves away monotonously. They had lowered the door, but still left it open upon the merest crack and out of this one or the other would peek at intervals, listening, heart in throat, for the dreaded sound of footfalls. But no one came.

"I thought I hearrd a kind of rustling once," Archer said fearfully.

"There's a couple of cows 'way over in a field," said Tom; "they might have made some sound."

After what seemed to them an age, the leaves over the opening seemed bathed in a strange new light and glistened here and there.

"That crack faces the west," said Tom. "The sun's beginning to go down."

"How do you know?" asked Archer.

"I always knew that up at Temple Camp. I don't know how I know. The morning sun is different from the afternoon sun, that's all. I think it'll set now in about two hours."36

"I wonder when she'll come," Archer said.

"Not till it's good and dark, that's sure. She's got to be careful. Maybe this place can be seen from the road, for all we know. Remember, we didn't see it in the daylight."

"Sh-h-h," said Archer. "Listen."

From far, far away there was borne upon the still air a dull, spent, booming sound at intervals.

"It's the fighting," whispered Tom.

"Wherre do you suppose it is?" Archer asked, sobered by this audible reminder of their nearness to the seat of war.

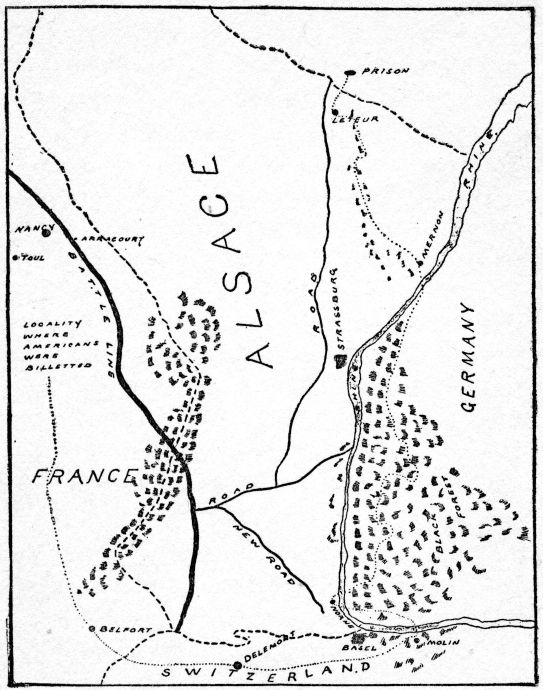

"I don't know," Tom said. "I'm kind of mixed up. That feller in the prison had a map. Let's see. I think Nancy's the nearest place to here. Toul is near that. That's where our fellers are—around there. Listen!"

Again the rumbling, faint but distinctly audible, almost as if it came from another world.

"The trenches run right through there—near Nancy," said Tom.

"Maybe it's ourr boys, hey?" Archer asked excitedly.

Tom did not answer immediately. He was thrilled at this thought of his own country speaking so that he, poor fugitive that he was, could hear it37 in this dark, lonesome dungeon in a hostile land, across all those miles.

"Maybe," he said, his voice catching the least bit. "They're in the Toul sector. A feller in prison told me. You don't feel so lonesome, kind of, when you hear that——"

"Gee, I hope we can get to them," said Archer.

"What you got to do, you can do," Tom answered. "I wonder——"

"Sh-h. D'you hearr that?" Archer whispered, clutching Tom's shoulder. "It was much nearerr—right close——"

They held their breaths as the reverberation of a sharp report died away.

"What was it?" Archer asked tensely.

"I don't know," Tom whispered, instinctively removing the short stick and closing the trap door tight. "Don't move—hush!"

CHAPTER VI

PRISONERS AGAIN

"Do you hear footsteps?" Archer breathed.

Tom listened, keen and alert. "No," he said at last. "There's no one coming."

"What do you s'pose it was?"

"I don't know. Sit down and don't get excited."

But Tom was trembling himself, and it was not until five or ten minutes had passed without sound or happening that he was able to get a grip on himself.

"Push up the door a little and listen," suggested Archer.

Tom cautiously pressed upward, but the door did not budge. "It's stuck," he whispered.

Archer rose and together they pressed, but save for a little looseness the door did not move.

"It's caught outside, I guess," said Tom. "Maybe the iron hasp fell into the padlock when I put it down, huh?"39

That, indeed, seemed to be the case, for upon pressure the door gave a little at the corners, but not midway along the side where the fastening was. Archer turned cold at the thought of their predicament, and for a moment even Tom's rather dull imagination pictured the ghastly fate made possible by imprisonment in this black hole.

"There's no use getting excited," he said. "We get some air through the cracks and after dark she'll be here, like she said. It's beginning to get dark now, I guess."

But he could not sit quietly and wait through the awful suspense, and he pressed up against the boards at intervals all the way along the four sides of the door. On the side where the hinges were it yielded not at all. On the opposite side it held fast in the center, showing that by a perverse freak of chance it had locked itself. Elsewhere it strained a little on pressure, but not enough to afford any hope of breaking it.

"If it was only lowerr," Archer said, "so we could brace our shoulderrs against it, we might forrce it."

"And make a lot of noise," said Tom. "There's no use getting rattled; we'll just have to wait till she comes."40

"Yes, but it gives you the willies thinkin' about what would happen——"

"Well, don't let's think of it, then," Tom interrupted. "We should worry." And suiting his action to the word, he seated himself, drew up his knees, and clasped his hands over them. "We'll just have to wait, that's all."

"What do you suppose that sound was?" Archer asked.

"I don't know; some kind of a gun. It ain't the first gun that's been shot off in Europe lately."

For half an hour or so they sat, trying to make talk, and each pretended to himself and to the other that he was not worrying. But Tom, who had a scout's ear, started and his heart beat faster at every trifling stir outside. Then, as they realized that darkness must have fallen, they became more alert for sounds and a little apprehensive. They knew Florette would come quietly, but Tom believed he could detect her approach.

After a while, they abandoned all their pretence of nonchalant confidence and did not talk at all. Of course, they knew Florette would come in her own good time, but the stifling atmosphere of that musty hole and the thought of what might happen—41—

Suddenly there was a slight noise outside and then, to their great relief, the unmistakable sound of footfalls on the planks above them, softened by the thick carpet of matted vine.

"Sh-h, don't speak!" Tom whispered, his heart beating rapidly. "Wait till she unfastens it or says something."

For a few seconds—a minute—they waited in breathless suspense. Then came a slight rustle as from some disturbance of the vine, then footfalls, again, modulated and stealthy they seemed, on the door just above them. A speck of dirt, or an infinitesimal pebble, maybe, fell upon Archer's head from the slight jarring of some crack in the rough door. Then silence.

Breathlessly they waited, Archer nervously clutching Tom's arm.

"Don't speak," Tom warned in the faintest whisper.

Still they waited. But no other sound broke upon the deathlike solitude and darkness....

CHAPTER VII

WHERE THERE'S A WILL——

"They're hunting for us," whispered Tom hoarsely. "It's good it was shut."

"I'd ratherr have them catch us," shivered Archer, "than die in herre."

"We haven't died yet," said Tom, "and they haven't caught us either. Don't lose your nerves. She'll come as soon as she can."

For a few minutes they did not speak nor stir, only listened eagerly for any further sound.

"What do you s'pose that shot was?" Archer whispered, after a few minutes more of keen suspense.

"I don't know. A signal, maybe. They're searching this place for us, I guess. Don't talk."

Archer took comfort from Tom's calmness, and for half an hour more they waited, silent and apprehensive. But nothing more happened, the solemn stillness of the countryside reigned without,43 and as the time passed their fear of pursuit and capture gave way to cold terror at the thought of being locked in this black, stifling vault to die.

What had happened? What did that shot mean, and where was it? Why did Florette not come? Who had walked across the plank roof of that musty prison? The fact that they could only guess at the time increased their dread and made their dreadful predicament the harder to bear. Moreover, the air was stale and insufficient and their heads began to ache cruelly.

"We can't stand it in here much longer," Tom confessed, after what seemed a long period of waiting. "Pretty soon one of us will be all in and then it'll be harder for the other. We've got to get out, no matter what."

"Therre may be a Gerrman soldierr within ten feet of us now," Archer said. "They'rre probably around in this vineyarrd somewherre, anyway. If we tried to forrce it open they'd hearr us."

"We couldn't force it, anyway," Tom said.

"My head's pounding like a hammerr," said Archer after a few minutes more of silence.

"Hold some of that damp straw to it.—How many matches did she give you?"

"'Bout a dozen or so."44

"Wish I had a knife.—Have you got that piece of wire yet?"

"Surre I have," said Archer, hauling from his pocket about five inches of barbed wire—the treasured memento of his escape from the Hun prison camp. "You laughed at me for always gettin' sooveneerrs; now you see—— What you want it for?"

"Sh-h. How many barbs has it?" asked Tom in a cautious whisper.

"Three."

"Let's have it; give me a couple o' matches, too."

Holding a lighted match under the place where he thought the iron padlock band must be, he scrutinized the under side of the door for any sign of it.

"I thought maybe the ends of the screws would show through," he said.

"What's the idea?" Archer asked. "Gee, but my head's poundin'."

"If that hasp just fell over the padlock eye," Tom whispered, "and didn't fit in like it ought to, maybe if I could bore a hole right under it I could push it up. Don't get scared," he added impassively. "There's another way, too; but it's a lot of work and it would make a noise. We'd just have to settle down and take turns and dig through with the wire barbs. I wish we had more matches. Don't get45 rattled, now. I know we're in a dickens of a hole——"

"You said something," observed Archer.

"I didn't mean it for a joke," said Tom soberly.

"This has got the trenches beat a mile," Archer said, somewhat encouraged by Tom's calmness and resourcefulness.

Striking another match, Tom examined more carefully the area of planking just in the middle of the side where he knew the hasp must be. He determined the exact center as nearly as he could. While doing this he dug his fingernails under a large splinter in the old planking and pulled it loose. Archer could not see what he was doing, and something deterred him from bothering his companion with questions.

For a while Tom breathed heavily on the splintered fragment. Then he tore one end of it until it was in shreds.

"Let's have another match."

Igniting the shredded end, he blew it deftly until the solid wood was aflame, and by the light of it he could see that Archer was ghastly pale and almost on the point of collapse. Their dank, unwholesome refuge seemed the more dreadful for the light.

"You got to just think about our getting out,"46 Tom said, in his usual dull manner. "We won't suffocate near so soon if we don't think about it, and don't get rattled. We got to get out and so we will get out. Let's have that wire."

All Archer's buoyancy was gone, but he tried to take heart from his comrade's stolid, frowning face and quiet demeanor.

"We can set fire to the whole business if we have to," said Tom, "so don't get rattled. We ain't going to die. Here, hold this."

Archer held the stick, blowing upon it, while Tom heated an end of the wire, holding the other end in some of the damp straw. As soon as it became red hot he poked it into the place he had selected above him. It took a long time and many heatings to burn a hole an eighth of an inch deep in the thick planking, and their task was not made the pleasanter by the thought that after all it was like taking a shot in the dark. It seemed like an hour, the piece of splintered wood was burned almost away, and what little temper there was in the malleable wire was quite gone from it, when Tom triumphantly pushed it through the hole.

"Strike anything?" Archer asked, in suspense.

"No," said Tom, disappointed. He bent the wire and, as best he could, poked it around outside. "I47 think I can feel it, though. Missed it by about an inch. There's no use getting discouraged. We'll just have to bore another one."

Long afterward, Archibald Archer often recalled the patience and doggedness which Tom displayed that night.

"As long's the first hole has helped us to find something out, it's worth while, anyway," he said philosophically.

Resolutely he went to work again, like the traditional spider climbing the wall, heating the almost limp wire and by little burnings of a sixteenth of an inch or so at a time he succeeded in making another hole through the heavy planking. But this time the wire encountered a metallic obstruction. Sure enough, Tom could feel the troublesome hasp, but alas, the wire was now too limber to push it up.

"I can just joggle it a little," he said, "but it's too heavy for this wire."

However, by dint of doubling and twisting the wire, he succeeded after many attempts and innumerable straightenings of the wire, in joggling the stubborn hasp free from the padlock eye on which it had barely caught.

"There it goes!" he said with a note of triumph in his usually impassive voice.48

Instantly Archer's hands were against the door ready to push it up.

"Wait a minute," whispered Tom; "don't fly off the handle. How do we know who's wandering round? Sh-h! Think I want to run plunk into the Prussian soldier that walked over our heads? Take your time."

In his excitement Archer had forgotten that ominous tread above their prison, and he drew back while Tom raised the door to the merest crack and peered cautiously out. The fresh air afforded them infinite relief.

The night was still and clear, the sky thick with stars. Far away a range of black heights was outlined against the sky, and over there the moon was rising. It seemed to be stealthily creeping up out of that battle-scourged plain in France for a glimpse of Alsace. It was from beyond those mountains that had come the portentous rumblings which they had heard.

"The blue Alsatian mountains," murmured Tom. "I wish we were across them."

"We'll have to go down and around if we everr get therre," Archer said.

"Sh-h-h!" warned Tom, putting his head out and peering about while Archer held the lid up.49

The moonlight, glinting down through the interstices of the trellised vine, made animated shadows in the quiet vineyard, conjuring the wooden supports and knotty masses of vine stalk into lurking human forms. Here some grim figure waited in silence behind an upright, only to dissolve with the changing light. There an ominous helmet seemed to stir amid the thick growth.

The two fugitives, elated at their deliverance, but tremblingly apprehensive, stood hesitating at so radical a move as complete emergence from their hiding place.

"We can't crawl out of herre in daylight, that's surre," whispered Archer. "D'you think maybe she'll come even now—if we waited?"

"It must be long after midnight," Tom answered. "You wait here and hold the door up while I crawl out. Don't move and don't speak. What's that shining over there? See?"

"Nothin' but an old waterring can."

"All right—sh-h-h!"

Cautiously, silently, Tom crept out, peering anxiously in every direction. Stealthily he raised himself. Then suddenly he made a low sound and with a rapidity which startled Archer, dropped to his hands and knees.50

"What's the matterr?" Archer whispered. "Come inside—quick!"

But Tom was engrossed with something on the ground.

"What is it?" Archer whispered anxiously. "His footprints?"

"Yop," said Tom, less cautiously. "Come on out. He's standing over there in the field now. Come on out, don't be scared."

Archer did not know what to make of it, but he crept out and looked over to the adjacent field where Tom pointed. A kindly, patient cow, one of those they had seen before, was grazing quietly, partaking of a late lunch in the moonlight.

"Here's her footprint," said Tom simply. "She gave us a good scare, anyway."

"Well—I'll—be——" Archer began.

"Sh-h!" warned Tom. "We don't know yet why Frenchy's sister don't come. But there weren't any soldiers here—that's one sure thing. We had a lot of worry for nothin'. Come on."

CHAPTER VIII

THE HOME FIRE NO LONGER BURNS

"That's the first time I was everr scarred by a cow," said Archer, his buoyant spirit fully revived, "but when I hearrd those footsteps overr my head, go-od night! It's good you happened to think about looking for footprints, hey?"

"I didn't happen to," said Tom. "I always do. Same as you never forget to get a souvenir," he added soberly.

"I'd like to get a sooveneerr from that cow, hey? You needn't talk; if it hadn't been for that wire, where'd we be now? Sooveneerrs arre all right. But I admit you've got to have ideas to go with 'em."

"Thanks," said Tom.

"Keep the change," said Archer jubilantly. "Believe me, I don't carre what becomes of me as long as I'm above ground—on terra cotta——"

"We've got to get away from here before daylight, so come on," interrupted Tom.52

"Are we going up to the house?"

"What else can we do?"

The explanation of those appalling footfalls by no means explained the failure of Florette to keep her promise, and the fugitives started along the path which led to the house.

They walked very cautiously, Tom scrutinizing the earth-covered planking for any sign of recent passing. The door of the stone kitchen stood open, which surprised them, and they stole quietly inside. A lamp stood upon the table, but there was no sign of human presence.

Tom led the way on tiptoe through the passage where they had passed before, and into the main room where another lamp revealed a ghastly sight. The heavy shutters were closed and barred, just as Florette had closed them when she had brought the boys into the room. Upon the floor lay old Pierre, quite dead, with a cruel wound, as from some blunt instrument, upon his forehead. His whitish gray hair, which had made him look so noble and benignant, was stained with his own blood. Blood lay in a pool about his fine old head, and the old coat which he wore had been torn from him, showing the stump of the arm which he had so long ago given to his beloved France.53

Near him lay sprawled upon the floor a soldier in a gray uniform, also dead. A little bullet wound in his temple told the tale. Beside him was a black helmet with heavy brass chin gear. Archer picked it up with trembling hands. Across its front was a motto:

"Mitt Gott—und Vaterland."

The middle of it was obscured by the flaring German coat-of-arms. A pistol lay midway between the two bodies and part of an old engraved motto was still visible on that. Tom could make out the name Napoleon.

"What d'you s'pose happened?" whispered Archer, aghast.

Tom shook his head. "Come on," said he. "Let's look for the others."

Taking the lamp, he led the way silently through the other rooms. On a couch in one of these was laid a soldier's uniform and a loose paper upon the floor showed that it had but lately been unwrapped. There was no sign of Florette or her mother, and Tom felt somewhat relieved at this, for he had feared to find them dead also.

"What d'you think it means?" Archer asked again, as they returned to the room of death.54

"I suppose they came for her just like she said," Tom answered in a low tone. "Her father must have shot the soldier, and probably whoever killed the old man took her and her mother away."

He looked down at the white, staring face of old Pierre and thought of how the old soldier had risen from his seat and had stood waiting with his fine military air at the moment of his own arrival at the shadowed and stricken home. He remembered how the old man had waited eagerly for his daughter to translate his and Archer's talk and of his humiliation at the shabby hospitality he must offer them. He took the helmet, a grim-looking thing, from the table where Archer had laid it, and read again, "Mitt Gott——"

It seemed to Tom that this was all wrong—that God must surely be on the side of old Pierre, no matter what had happened.

"Do you know what I think?" he said simply. "I think it was just the way I said—and like she said. They came to get her and maybe they didn't treat her just right, and her father hit one of them. Or maybe he shot him first off. Anyway, I think that soldier suit must be the one Frenchy had to wear, 'cause he told me that the boys in Alsace had to drill even before they got out of school. I guess she55 was going to bring it to us so one of us could wear it.... We got to feel sorry for her, that's one sure thing."

It was Tom's simple, blunt way of expressing the sympathy which surged up in his heart.

"I liked her; she treated us fine," said Archer.

For a few seconds Tom did not answer; then he said in his old stolid way, "I don't know where they took her or what they'll make her do, but anybody could see she didn't have any muscle. Whenever I think of her I'll fight harder, that's one sure thing."

For a few moments he could hardly command himself as he contemplated this tragic end of the broken home. Florette, whom he had seen but yesterday, had been taken away—away from her home, probably from her beloved Alsace, to enforced labor for the Teuton tyrant. He recalled her slender form as she hurried through the darkness ahead of them, her gentle apology for their poor reception, her wistful memories of her brother as she showed them their hiding-place, her touching grief and apprehension as she stood talking with him under the trellis....

And now she was gone and awful thoughts of her peril and suffering welled up in Tom's mind.56

He looked at the stark figure and white, staring face of old Pierre and thought of the impetuous embrace the old man had given him. He thought of his friend, Frenchy. And the mother—where was she? Good people, kind people; trying in the menacing shadow of the detestable Teuton beast to keep their flickering home fire burning. And this was the end of it.

Most of all, he thought of Florette and her wistful, fearful look haunted him. "Maybe for ze great Krupps"—the phrase lingered in his mind and he stood there appalled at the realization of this awful, unexplained thing which had happened.

Then Tom Slade did something which his scout training had taught him to do, while Archer, tremulous and unstrung, stood awkwardly by, watching. He knelt down over the lifeless form of the old man and straightened the prostrate figure so that it lay becomingly and decently upon the hard floor. He bent the one arm and laid it across the breast in the usual posture of dignity and peace. He took the threadbare covering from the old melodeon and placed it over the face. So that the last service for old Pierre Leteur was performed by an American boy; and at least the ashes of the home fire were left in order by a scout from far across the seas.57

"It's part of first aid," explained Tom quietly, as he rose; "I learned how at Temple Camp."

Archer said nothing.

"When a scout from Maryland died up there, I saw how they did it."

"You got to thank the scouts for a lot," said Archer; "forr trackin' an' trailin'——"

"'Tain't on account of them," said Tom, his voice breaking a little, "it's on account of her——"

And he kneeled again to arrange the corner of the cloth more neatly over the wrinkled, wounded face....

CHAPTER IX

FLIGHT

"Anyway, we've got to get away from here quick," said Tom, pulling himself together; "never mind about clothes or anything. One thing sure, they'll be back here soon. See if he has a watch," he added, indicating the dead soldier.

"No, but he's got a little compass around his neck; shall I take it?"

"Sure, we got a right to capture anything from the enemy."

"He's got some papers, too."

"All right, take 'em. Come on out through the kitchen way—hurry up. Don't make any noise. You look for some food—I'll be with you right away."

Tom crept cautiously out to the road and, kneeling, placed his ear to the ground. There was no sound, and he hurried back to the stone kitchen where Archer was stuffing his pockets with such dry edibles as he could gather.59

"All right, come on," he whispered hurriedly. "What have you got?"

"Some hard bread and a couple of salt fish——"

"Give me one of those," Tom interrupted: "and hand me that tablecloth. Come on. Got some matches?"

"Yes, and a candle, too."

"Good. Don't strike a light. You go ahead, along the plank walk."

Leaving the scene of the tragedy, they hurried along the board walk under the trellis, Tom dragging the tablecloth so that it swept both of the narrow planks and obliterated any suggestion of footprints. When they had gone about fifty yards he stooped and flung the salt fish from him so that it barely skimmed the earth and rested at some distance from the path.

"If they should have any dogs with 'em, that'll take 'em off the trail," he said.

"I'm sorry I didn't get you a souveneerr too," said Archer, as they hurried along.

This was the first intimation Tom had that Archer regarded the little compass merely as a souvenir.

"You can give me those papers you took," he said, half in joke.60

"It's only an envelope," Archer said. "Have you got your button all right?"

"Sure."

When they reached the wine vat, Tom threw the old tablecloth into it, and pulled the vine more carefully so as to conceal the door. They were tempted to rest here, but realized that if they spent the balance of the night in their former refuge it would mean another long day in the dank hole.

The vineyard ended a few yards from the wine vat and beyond was an area of open lowlands across which the boys could see a range of low wooded hills.

"We've got about four hours till daylight," said Tom; "let's make for those woods."

"That's east," said Archer. "We want to go south."

"We want to see where we're going before we go anywhere," Tom answered. "If we can get into the woods on those hills, we can climb a tree tomorrow and see where we're at. What I want is a bird's-eye squint to start off with, 'cause we can't ask questions of anybody."

"No, and believe me, we don't want to run into any cities," said Archer. "We got through one night anyway, hey?"61

Notwithstanding that they were without shelter, and facing the innumerable perils of a hostile country about which they knew nothing, they still found action preferable to inaction and their spirits rose as they journeyed on with the star-studded sky overhead.

They found the meadows low and marshy, which gratified Tom who was always fearful of leaving footprints. The hills beyond were low and thickly wooded, the face of the nearest being broken by slides and forming almost a precipice surmounted by a jumble of rocks and underbrush. The country seemed wild and isolated enough.

"I suppose it's the beginning of the Alps, maybe," Tom panted as they scrambled up.

"There's nobody up here, that's surre," Archer answered.

"We'll just lie low till daylight and see if we can get a squint at the country. Then tomorrow night we'll hike it south. If we go straight south we've got to come to Switzerland."

"It's lucky we've got the compass," said Archer.

"Maybe this is a ridge we're on," Tom said. "If it is, we're in luck. We may be able to go thirty or forty miles along it. One thing sure, it'll be more hilly the farther south we get 'cause we'll be getting62 into the beginning of the Alps. There ought to be water up here."

"I wish there were some apples," said Archer.

"You're always thinking about apples and souvenirs. Let's crawl in under here."

They had scrambled to the top of the precipitous ascent and found themselves upon the broken edge of the forest amid a black chaos of piled up rock and underbrush. Evidently, the land here was giving way, little by little, for here and there they could see a tree canting tipsily over the edge, its network of half-exposed roots making a last gallant stand against the erosive process and helping to hold the weight of the great boulders which ere long would crash down into the marshy lowlands.

They crept into a sort of leafy cave formed by a fallen tree and stretched their weary bodies and relaxed their tense nerves after what had seemed a nightmare.

"As long as we're going to join the army," said Tom, "we might as well make a rule now. We won't both sleep at the same time till we're out of Germany. We got to live up to that rule no matter how tired we get."

"I'm game," said Archer. "You go to sleep now and when I get good and sleepy I'll wake you up."63

"In about two hours," said Tom. "Then you can sleep till it's light. Then we'll see if it's safe to stay here. Keep looking in that direction—the way we came. And if you see any lights, wake me up."

Archer did not obey these directions at all, for he sat with his hands clasped over his knees, gazing down across the dark marshland below. Two hours, three hours, four hours, he sat there and scarcely stirred. And as the time dragged on and there were no lights and no sounds he took fresh courage and hope. He was beginning to realize the value of the stolid determination, the resourcefulness, the keen eye and stealthy foot and clear brain of the comrade who lay sleeping at his side. He had wanted to tell Tom Slade what he thought of him and how he trusted him, but he did not know how. So he just sat there, hour in and hour out, and let the weary pathfinder of Temple Camp sleep until he awoke of his own accord.

"All right," said Archer then, blinking. "Nothing happened."

CHAPTER X

THE SOLDIER'S PAPERS

All that day they stayed in their leafy refuge. They could look down across the marshy meadows they had crossed to the trellised vineyard of the Leteurs, looking orderly and symmetrical in the distance like a two-storied field, and beyond that the massive gables of the gray, forsaken house.

They could see the whole neighboring country in panorama. Other houses were discernible at infrequent intervals along the road which wound southward through the lowland between the hills where the boys were and the Vosges Mountains (the "Blue Alsatian Mountains") to the west. Through the long, daylight hours Tom studied the country carefully. Now, as never before (for he knew how much depended on it), he watched for every scrap of knowledge which might afford any inference or deduction to help them in their flight.

"You can see how it is," he told Archer, as they65 watched the little compass needle, waiting for it to settle. "This is a ridge and it runs north and south. I kind of think it's the west side of the valley of a river, like Daggett's Hills are to Perch River up your way."

"I'd like to be therre now," said Archer.

"I'd rather be in France," Tom answered.

"Of course it'll fizzle out in places and we'll come to villages, but there's enough woods ahead of us for us to go twenty miles tonight. That's the way it seems to me, anyway."

Once Tom ventured out on hands and knees into the woods in quest of water, and returned with the good news that he had had a refreshing drink from a brook to which he directed Archer.

"Do you know what this is?" he said, emptying an armful of weeds on the ground. "It's chicory. If I dared to build a fire I could make you a good imitation of coffee with that. But we can eat the roots, anyway. Now I remember it used to be in the geography in school about so much chicory growing in the Alps——"

"Oh, Ebeneezerr!" shouted Archer, much to Tom's alarm. "I'm glad you said that 'cause it reminds me about the mussels."

"The what?"66

"'The mountain streams abound with the pearrl-bearing mussels which are a staple article of diet with the Alpine natives,'" quoted Archer in declamatory style. "I had to write that two hundred and fifty times f'rr whittlin' a hole in the desk——"

"I s'pose you were after a souvenir," said Tom dryly.

"Firrst I wrote it once 'n' then I put two hundred and forty-nine ditto marrks. Ebenezerr! Wasn't the teacherr mad! I had to write it two hundred and fifty times f'rr vandalism and two hundred and fifty morre f'rr insolence."

"Served you right," said Tom.

"Oh, I guess you weren't such an angel in school either!" said Archer. "I'll never forget about those pearrl-bearing mussels as long as I live—you can bet!"

Tom separated the chicory roots from the stalks and Archer went to wash them in the stream. In a little while he returned with a triumphant smile all over his round, freckled face and half a dozen mussels in his cupped hands.

"Now what have you got to say, huh? It's good I whittled that desk and was insolent—you can bet!"

Tom's practical mind did not quite appreciate this line of reasoning, but he was glad enough to see the67 mussels, the very look of which was cool and refreshing.

"I always said I had no use for geographies except to put mustaches and things on the North Pole explorers and high hats on Columbus and Henry Hudson, but, believe me, I'm glad I remembered about those pearrl-bearing mussels—hey, Slady? I hope the Alpine natives don't take it into their heads to come up herre afterr any of 'em just now. I just rooted around in the mud and got 'em. Look at my hand, will you?"

They made a sumptuous repast of wet, crisp chicory roots and "pearrl-bearing mussels" as Archer insisted upon calling them, although they found no pearls. The meal was refreshing and not half bad. There was a pleasant air of stealth and cosiness about the whole thing, lying there in their leafy refuge in the edge of the woods with the Alsatian country stretched below them. Perhaps it was the mussels out of the geography (to quote Archer's own phrase) as well as the sense of security which came as the uneventful hours passed, but as the twilight gathered they enjoyed a feeling of safety, and their hope ran high. They had found, as the scout usually finds, that Nature was their friend, never withholding her bounty from68 him who seeks and uses his resourcefulness and brains.

All through the long afternoon they could distinguish heavy army wagons with dark spots on their canvas sides (the flaring, arrogant German crest which allied soldiers had grown to despise) moving northward along the distant road. They looked almost like toy wagons. Sometimes, when the breeze favored, they could hear the rattle of wheels and occasionally a human voice was faintly audible. And all the while from those towering heights beyond came the spent, muffled booming.

"I'd like to know just what's going on over there," Tom said as he gazed at the blue heights. "Maybe those wagons down there on the road have something to do with it. If there's a big battle going on they may be bringing back wounded and prisoners.—Some of our own fellers might be in 'em."

They tried to determine about where, along that far-flung line, the sounds arose, but they could only guess at it.

"All I know is what I hearrd 'em say in the prison camp," said Archer; "that our fellers are just the otherr side of the mountains."

"That would be Nancy," said Tom thoughtfully.69

"That Loquet feller that got capturred in a raid," Archer said, "told me the Americans were all around therre, just the otherr side of the mountains—in a lot of differrent villages: When they get through training they send 'em ahead to the trenches. Some of 'em have been in raids already, he said."

"You have to run like everything in a raid," said Tom. "I'd like to be in one, wouldn't you?"

"Depends on which way I was running.—Let's have a look at these paperrs before it gets too darrk, hey?" he added, hauling from his pocket the papers which he had taken from the dead Boche. "I neverr thought about 'em till just now?"

"I thought about it," said Tom, who indeed seldom forgot anything, "but I didn't say anything about it 'cause it kind of makes me think about what happened—I mean how they took her away," he added, in his dull way.

For a minute they sat silently gazing down at the vineyard which was now touched with the first crimson rays of sunset.

"You can just see the chimney," Tom said; "see, just left of that big tree.—I hope I don't see Frenchy any more now 'cause I wouldn't like to have to tell him——"70

"We don't know what happened," said Archer. "Maybe therre werren't any otherr soldierrs; she may have escaped—and her motherr, too."

"It's more likely there were others, though," said Tom. "I keep thinking all the time how scared she was and it kind of——"

"Let's look at the papers," said Archer.

The German soldier must have been a typical Boche, for he carried with him the customary baggage of written and statistical matter with which these warriors sally forth to battle.

"He must o' been a walking correspondence school," said Archer, unfolding the contents of the parchment envelope. "Herre's a list—all in German. Herre's some poetry—or I s'pose it's poetry, 'cause it's printed all in and out."

"Maybe it's a hymn of hate," said Tom.

"Herre's a map, and herre's a letter. All in Gerrman—even the map. Anyway, I can't understand it."

"Looks like a scout astronomy chart," said Tom. "It's all dots like the big dipper."

"Do you s'pose it means they're going to conquer the sky and all the starrs and everything?" Archer asked. "Here's a letter, it's dated about two weeks ago—I can make out the numbers all right."71

The letter was in German, of course, and Archer, who during his long incarceration in the prison camp had picked up a few scraps of the language, fell to trying to decipher it. The only reward he had for his pains was a familiar word which he was able to distinguish here and there and which greatly increased their desire to know the full purport of the letter.

"Herre's President Wilson's name.—See!" said Archer excitedly. "And herre's America——"

"Yes, and there it is again," said Tom. "That must be Yankees, see? Something or other Yankees. It's about a mile long."

"Jim-min-nitty!" said Archer, staring at the word (presumably a disparaging adjective) which preceded the word Yankees. "It's got one—two—three—wait a minute—it's got thirty-seven letters to it. Go-o-od night!"

"And that must be Arracourt," said Tom. "I heard about that place—it ain't so far from Nancy. Gee, I wish we could read that letter!"

"I'd like to know what kind of a Yankee a b-l-o-e——"

But Archer gave it up in despair.

CHAPTER XI

THE SCOUT THROUGH ALSACE

As soon as it was dark they started southward, following the ridge. Their way took them up hill and down dale, through rugged uplands where they had to travel five miles to advance three, picking their way over the trackless, rocky heights which formed the first foothills of the mighty Alps.

"S'pose we should meet some one?" Archer suggested, as he followed Tom's lead over the rocky ledges.

"Not up here," said Tom. "You can see lights way off south and maybe we'll have to pass through some villages tomorrow night, but not tonight. We'll only do about twelve miles tonight if it keeps up like this."

"S'pose somebody should see us—when we'rre going through a village? We'll tell him we'rre herre to back the Kaiser, hey?"

"S'pose he's a Frenchman that belongs in Alsace," Tom queried.73

"Then we'll add on out o' France. We'll say—look out for that rock!—We'll just say we'rre herre to back the Kaiser, and if he looks sourr we'll say; out o' France. Back the Kaiser out o' France. We win either way, see? A fellerr in prison told me General Perrshing wants a lot of men with glass eyes—to peel onions. Look out you don't trip on that root! Herre's anotherr. If you'rre under sixteen what part of the arrmy do they put you in? The infantry, of course. Herre's——"

"Never mind," laughed Tom. "Look where you're stepping."

"What I'm worrying about now," said Archer, his spirits mounting as they made their way southward, "is how we're going to cross the frontierr when we get to it. They've got a big tangled fence of barrbed wirre all along, even across the mountains, to where the battleline cuts in. And it's got a good juicy electric current running through it all the time. If you just touch it—good night!"

"I got an idea," said Tom simply.

"If I could get a piece of that electrified wirre for a souveneerr," mused Archer, "I'd——"

"You'll have a broken head for a souvenir in a minute," said Tom, "if you don't watch where you're going."74

"Gee, you've got eyes in your feet," said Archer admiringly.

"Whenever you see a fallen tree," said Tom, "look out for holes. It means the earth is thin and weak all around and couldn't hold the roots."

"It ought to drink buttermilk, hey?" said Archer flippantly, "if it's thin and pale."

"I said thin and weak," said Tom. "Do you ever get tired talking?"

"Sure—same as a phonograph record does."

So they plodded on, encircling areas of towering rock or surmounting them when they were not too high, and always working southward. Tom, who was not unaccustomed to woods and mountains, thought he had never before traversed such a chaotic wilderness. He would have given a good deal for a watch and for some means of knowing how much actual distance they were covering. It was slow, tiresome work.

Every little while he would check their course by the little compass, to see which he often had to light one of their few precious matches.

"One thing surre, we won't meet anybody up herre," said Archer, as he scrambled along. "See those little lights over to the east?"

"Don't worry," said Tom, "that's twenty miles75 away. We're all right up here. There were some lights further down too and one over that way but I can't see them now. I guess it's after midnight. Sh-h-h. Listen!"

They stood stark still, Archer gripping Tom's arm.

"It's water trickling," said Tom dully.

"Gee, you had the life scared out of me!" breathed Archer.

A little farther on they came to an abrupt, rocky declivity which crossed their course and in the bottom of which was a swift running stream.

"It's running east," said Tom, listening intently. "I can tell by the ripples."

"Yes, you can!" said Archer contemptuously.

"Sure I can," Tom answered. He held his hand first to his right ear, then to his left. "The long, washy sound comes first when you close your left ear, so I know the water's flowing that way. It's easy," he added.