The Old Mansion by Moonlight—

[xvi]

| A man might then behold |

| At Christmas, in each hall |

| Good fires to curb the cold, |

| And meat for great and small. |

| The neighbours were friendly bidden, |

| And all had welcome true, |

| The poor from the gates were not chidden, |

| When this old cap was new. |

| Old Song. |

[1]

![CHRISTMAS CHRISTMAS]()

![T T]()

here is nothing in England that exercises a more delightful spell over

my imagination than the lingerings of the holiday customs and rural

games of former times. They recall the pictures my fancy used to draw in

the May morning of life, when as yet I only knew the world through

books, and believed it to be all that poets had painted it; and they

bring with them the flavour of those honest days of yore, in which,

perhaps with equal fallacy, I am apt to think the world was more

home-bred, social, and joyous than at present. I regret to say that they

are daily growing more and more faint, being gradually [2] worn away by

time, but still more obliterated by modern fashion. They resemble those

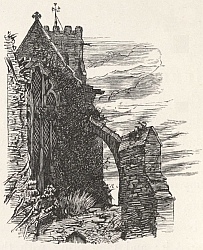

picturesque morsels of Gothic architecture which we see crumbling in

various parts of the country, partly dilapidated by the waste of ages,

and partly lost in the additions and alterations of latter days. Poetry,

however, clings with cherishing fondness about the rural game and

holiday revel, from [3] which it has derived so many of its themes—as the

ivy winds its rich foliage about the Gothic arch and mouldering tower,

gratefully repaying their support by clasping together their tottering

remains, and, as it were, embalming them in verdure.

![The Mouldering Tower The Mouldering Tower]()

Of all the old festivals, however, that of Christmas awakens the

strongest and most heartfelt associations. There is a tone of solemn and

sacred feeling that blends with our conviviality, and lifts the spirit

to a state of hallowed and elevated enjoyment. The services of the

church about this season are extremely tender and inspiring. They dwell

on the beautiful story of the origin of our faith, and the pastoral

scenes that accompanied its announcement. They gradually increase in

fervour and pathos during the season of Advent, until they break forth

in full jubilee on the morning that brought peace and good-will to men.

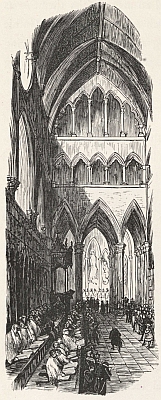

I do not know a grander effect of music on the moral feelings than to

hear the[4] full choir and the pealing organ performing a Christmas anthem

in a cathedral, and filling every part of the vast pile with triumphant

harmony.

![Christmas Anthem in Cathedral Christmas Anthem in Cathedral]()

It is a beautiful arrangement, also, derived from days of yore, that

this festival, which commemorates the announcement of the religion of

peace and love, has been made the season for gathering together of

family[5] connections, and drawing closer again those bands of kindred

hearts which the cares and pleasures and sorrows of the world are

continually operating to cast loose; of calling back the children of a

family who have launched forth in life, and wandered widely asunder,

once more to assemble about the paternal hearth, that rallying-place of

the affections, there to grow young and loving again among the endearing

mementoes of childhood.

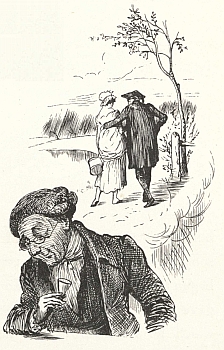

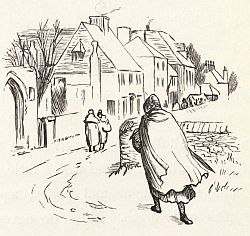

![The Wanderer's Return The Wanderer's Return]()

There is something in the very season of the year that gives a charm to

the festivity of Christmas. At other times we derive a great portion of

our pleasures from the mere beauties of nature.[6] Our feelings sally

forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we "live

abroad and everywhere." The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream,

the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer,

the golden pomp of autumn; earth with its mantle of refreshing green,

and heaven with its deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence, all

fill us with mute but exquisite delight, and we revel in the luxury of

mere sensation. But in the depth of winter, when nature lies despoiled

of every charm, and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for

our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of

the landscape, the short gloomy days and[7] darksome nights, while they

circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling

abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasures of the social

circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more

aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other's society, and

are brought more closely together by dependence on each other for

enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart; and we draw our pleasures from the

deep wells of living kindness, which lie in the quiet recesses of our

bosoms; and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of

domestic felicity.

!["Nature lies despoiled of every Charm" "Nature lies despoiled of every Charm"]()

!["The Honest Face of Hospitality" "The Honest Face of Hospitality"]()

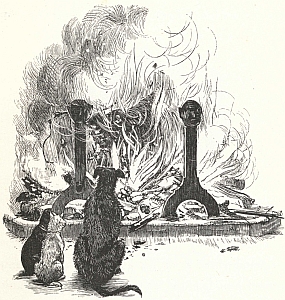

The pitchy gloom without makes the heart dilate on entering the room

filled with the glow and warmth of the evening fire. The ruddy blaze

diffuses an artificial summer and sunshine through the room, and lights

up each countenance into a kindlier welcome. Where does the honest face

of hospitality expand into a broader[8] and more cordial smile—where is

the shy glance of love more sweetly eloquent—than by the winter

fireside? and as the hollow blast of wintry wind rushes through the

hall, claps the distant[9] door, whistles about the casement, and rumbles

down the chimney, what can be more grateful than that feeling of sober

and sheltered security with which we look round upon the comfortable

chamber and the scene of domestic hilarity?

!["The Shy Glance of Love" "The Shy Glance of Love"]()

The English, from the great prevalence of rural habits throughout every

class of society, have always been fond of those festivals and holidays

which agreeably interrupt the stillness of country life; and they were,

in former days, particularly observant of the religious and social rites

of Christmas. It is inspiring to read even the dry details which some

antiquarians have given of the quaint humours, the burlesque pageants,

the complete abandonment to mirth and good-fellowship, with which this

festival was celebrated. It seemed to throw open every door, and unlock

every heart. It brought the peasant and the peer together, and blended

all ranks in one warm generous flow of joy and kindness. The old halls

of castles and manor-houses re[10]sounded with the harp and the Christmas

carol, and their ample boards groaned under the weight of hospitality.

Even the poorest cottage welcomed the festive season with green

decorations of bay and holly—the cheerful fire glanced its rays through

the lattice, inviting the passenger to raise the latch, and join the

gossip knot huddled round the hearth, beguiling the long evening with

legendary jokes and oft-told Christmas tales.

![Old Hall of Castle Old Hall of Castle]()

One of the least pleasing effects of modern refinement is the havoc it

has made among the hearty old holiday customs. It has completely taken

off the sharp touchings and spirited reliefs of these embellishments of

life, and has worn down society into a more smooth and polished,[11] but

certainly a less characteristic surface. Many of the games and

ceremonials of Christmas have entirely disappeared, and, like the

sherris sack of old Falstaff, are become matters of speculation and

dispute among commentators. They flourished in times full of spirit and

lustihood, when men enjoyed life roughly, but heartily and vigorously;

times wild and picturesque, which have furnished poetry with its richest

materials, and the drama with its most attractive variety of characters

and manners. The world has become more worldly. There is more of

dissipation, and less of enjoyment. Pleasure has expanded into a

broader, but a shallower stream, and has forsaken many of those deep and

quiet channels where it flowed sweetly through the calm bosom of

domestic life. Society has acquired a more enlightened and elegant tone;

but it has lost many of its strong local peculiarities, its home-bred

feelings, its honest fireside delights. The traditionary customs of

golden-hearted antiquity,[12] its feudal hospitalities, and lordly

wassailings, have passed away with the baronial castles and stately

manor-houses in which they were celebrated. They comported with the

shadowy hall, the great oaken gallery, and the tapestried parlour, but

are unfitted to the light showy[13] saloons and happy drawing-rooms of the

modern villa.

![The Great Oaken Gallery The Great Oaken Gallery]()

Shorn, however, as it is, of its ancient and festive honours, Christmas

is still a period of delightful excitement in England. It is gratifying

to see that home-feeling completely aroused which seems to hold so

powerful a place in every English bosom. The preparations making on

every side for the social board that is again to unite friends and

kindred; the presents of good cheer passing and repassing, those tokens

of regard, and quickeners of kind feelings; the evergreens distributed

about houses and churches, emblems of peace and gladness; all these have

the most pleasing effect in producing fond associations, and kindling

benevolent sympathies. Even the sound of the waits, rude as may be their

minstrelsy, breaks upon the mid-watches of a winter night with the

effect of perfect harmony. As I have been awakened by them in that still

and solemn hour, "when deep sleep falleth upon[14] man," I have listened

with a hushed delight, and connecting them with the sacred and joyous

occasion, have almost fancied them into another celestial choir,

announcing peace and good-will to mankind.

![The Waits The Waits]()

How delightfully the imagination, when wrought upon by these moral

influences, turns everything to melody and beauty: The very crowing of

the cock, who is sometimes heard in the profound repose of the country,

"telling the night watches to his feathery dames," was thought by the

common people to announce the approach of this sacred festival:[15]—

| "Some say that ever 'gainst that season comes |

| Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated, |

| This bird of dawning singeth all night long: |

| And then, they say, no spirit dares stir abroad; |

| The nights are wholesome—then no planets strike, |

| No fairy takes, no witch hath power to charm, |

| So hallow'd and so gracious is the time." |

Amidst the general call to happiness, the bustle of the spirits, and

stir of the affections, which prevail at this period, what bosom can

remain insensible? It is, indeed, the season of regenerated feeling—the

season for kindling, not merely the fire of hospitality in the hall, but

the genial flame of charity in the heart.

The scene of early love again rises green to memory beyond the sterile

waste of years; and the idea of home, fraught with the fragrance of

home-dwelling joys, re-animates the drooping spirit,—as the Arabian

breeze will sometimes waft the freshness of the distant fields to the

weary pilgrim of the desert.

Stranger and sojourner as I am in the land—though for me no social

hearth may blaze, no[16] hospitable roof throw open its doors, nor the warm

grasp of friendship welcome me at the threshold—yet I feel the

influence of the season beaming into my soul from the happy looks of

those around me. Surely happiness is reflective, like the light of

heaven; and every countenance, bright with smiles, and glowing with

innocent enjoyment, is a mirror transmitting to others the rays of a

supreme and ever-shining benevolence. He who can turn churlishly away

from contemplating the felicity of his fellow-beings, and sit down

darkling and repining in his loneliness when all around is joyful, may

have his moments of strong excitement and selfish gratification, but he

wants the genial and social sympathies which constitute the charm of a

merry Christmas.

[17]

[18]

[19]

THE STAGE COACH

n the preceding paper I have made some general observations on the

Christmas festivities of England, and am tempted to illustrate them by

some anecdotes of a Christmas passed in the country; in perusing which I

would most courteously invite my reader to lay aside the austerity of

wisdom, and to put on that genuine holiday spirit which is tolerant of

folly, and anxious only for amusement.

![The Three Schoolboys The Three Schoolboys]()

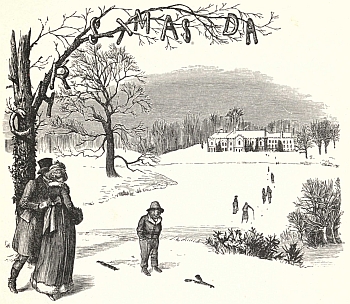

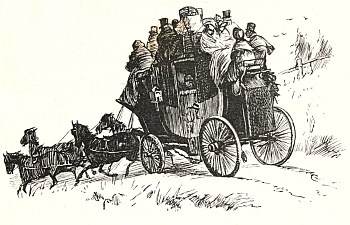

In the course of a December tour in Yorkshire, I rode for a long

distance in one of the public coaches, on the day preceding Christmas.[20]

The coach was crowded, both inside and out, with passengers, who, by

their talk, seemed principally bound to the mansions of relations or

friends to eat the Christmas dinner. It was loaded also with hampers of

game, and baskets and boxes of delicacies; and hares hung dangling their

long ears about the coachman's box,—presents from distant friends for

the impending feast. I had three fine rosy-cheeked schoolboys for my

fellow-passengers inside, full of the buxom health and manly spirit

which I have observed in the children of this country. They were

returning home for the holidays in high glee, and promising themselves a

world of enjoyment. It was delightful to hear the gigantic plans of

pleasure of the little rogues, and the impracticable feats they were to

perform during their six weeks' emancipation[21] from the abhorred thraldom

of book, birch, and pedagogue. They were full of anticipations of the

meeting with the family and household, down to the very cat and dog; and

of the joy they were to give their little sisters by the presents with

which their pockets were crammed; but the meeting to which they seemed

to look forward with the greatest impatience was with Bantam, which I

found to be a pony, and, according to their talk, possessed of more

virtues than any steed since the days of Bucephalus. How he could trot!

how he could run! and then such leaps as he would take—there was not a

hedge in the whole country that he could not clear.

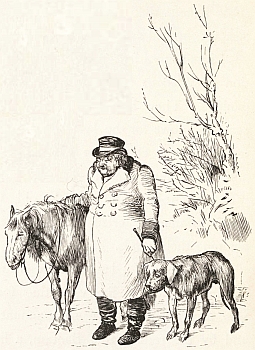

![The Old English Stage Coachman The Old English Stage Coachman]()

They were under the particular guardianship of the coachman, to whom,

whenever an opportunity presented, they addressed a host of questions,

and pronounced him one of the best fellows in the whole world. Indeed, I

could not but notice the more than ordinary air of bustle and[22]

importance of the coachman, who wore his hat a little on one side, and

had a large bunch of Christmas greens stuck in the button-hole of his

coat. He is always a personage full of mighty care and business, but he

is particularly so during this season, having so many commissions to

execute in consequence of the great interchange of presents. And here,

perhaps, it may not be unacceptable to my untravelled readers, to have a

sketch that may serve as a general representation of this very numerous

and important class of functionaries, who have a dress, a manner, a

language, an air, peculiar to themselves, and prevalent throughout the

fraternity; so that, wherever an English stage-coachman may be seen, he

cannot be mistaken for one of any other craft or mystery.

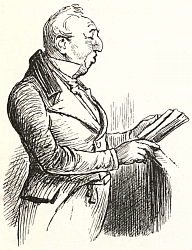

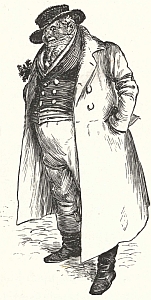

He has commonly a broad, full face, curiously mottled with red, as if

the blood had been forced by hard feeding into every vessel of the skin;

he is swelled into jolly dimensions by frequent pota[23]tions of malt

liquors, and his bulk is still further increased by a multiplicity of

coats, in which he is buried like a cauliflower, the upper one reaching

to his heels. He wears a broad-brimmed, low-crowned hat; a huge roll of

coloured handkerchief about his neck, knowingly knotted[24] and tucked in

at the bosom; and has in summer-time a large bouquet of flowers in his

button-hole; the present, most probably, of some enamoured country lass.

His waistcoat is commonly of some bright colour, striped; and his

small-clothes extend far below the knees, to meet a pair of jockey boots

which reach about half-way up his legs.

!["He throws down the Reins with something of an Air" "He throws down the Reins with something of an Air"]()

All this costume is maintained with much precision; he has a pride in

having his clothes of excellent materials; and, notwithstanding the

seeming grossness of his appearance, there is still discernible that

neatness and propriety of person, which is almost inherent in an

Englishman. He enjoys great consequence and consideration along the

road; has frequent conferences with the village housewives, who look

upon him as a man of great trust and dependence; and he seems to have a

good understanding with every bright-eyed country lass. The moment he

arrives where the horses are to be changed, he throws down the[25] reins

with something of an air, and abandons the cattle to the care of the

ostler; his duty being merely to drive from one stage to another. When

off the box, his hands are thrust in the pockets of his greatcoat, and

he rolls about the inn-yard with an air of the most absolute

lordli[26]ness. Here he is generally surrounded by an admiring throng of

ostlers, stable-boys, shoe-blacks, and those nameless hangers-on that

infest inns and taverns, and run errands, and do all kinds of[27] odd jobs,

for the privilege of battening on the drippings of the kitchen and the

leakage of the tap-room. These all look up to him as to an oracle;

treasure up his cant phrases; echo his opinions about horses and other

topics of jockey lore; and, above all, endeavour to imitate his air and

carriage. Every ragamuffin that has a coat to his back thrusts his hands

in the pockets, rolls in his gait, talks slang, and is an embryo

Coachey.

![The Stable Imitators The Stable Imitators]()

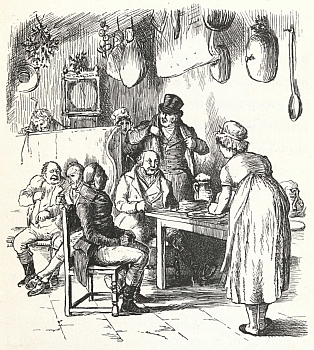

![The Public House The Public House]()

![The Housemaid The Housemaid]()

Perhaps it might be owing to the pleasing serenity that reigned in my

own mind, that I fancied I saw cheerfulness in every countenance

throughout the journey. A stage coach, however, carries animation always

with it, and puts the world in motion as it whirls along. The horn

sounded at the entrance of a village, produces a general bustle. Some

hasten forth to meet friends; some with bundles and bandboxes to secure

places, and in the hurry of the moment can hardly take leave of the

group that accompanies[28] them. In the meantime, the coachman has a world

of small commissions to execute. Sometimes he delivers a hare or

pheasant; sometimes jerks a small parcel or newspaper to the door of a

public-house; and sometimes, with knowing leer and words of sly import,

hands to some half-blushing, half-laughing housemaid an odd-shaped[29]

billet-doux from some rustic admirer. As the coach rattles through the

village, every one runs to the window, and you have glances on every

side of fresh country faces, and blooming giggling girls. At the corners

are assembled juntas of village idlers and wise men, who take their

stations there for the important purpose of seeing company pass; but the

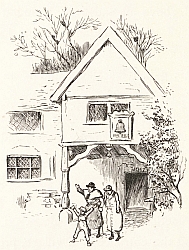

sagest knot is generally at the blacksmith's, to whom the passing of the

coach is an event fruitful of much speculation.[30] The smith, with the

horse's heel in his lap, pauses as the vehicle whirls by; the Cyclops

round the anvil suspend their ringing hammers, and suffer the iron to

grow cool; and the sooty spectre in brown paper cap, labouring at the

bellows, leans on the handle for a moment, and permits the[31] asthmatic

engine to heave a long-drawn sigh, while he glares through the murky

smoke and sulphureous gleams of the smithy.

![The Smithy The Smithy]()

!["Now or never must Music be in Tune" "Now or never must Music be in Tune"]()

Perhaps the impending holiday might have given a more than usual

animation to the country, for it seemed to me as if everybody was in

good looks and good spirits. Game, poultry, and other luxuries of the

table, were in brisk circulation in the villages; the grocers',

butchers', and fruiterers' shops were thronged with customers. The

housewives were stirring briskly about, putting their dwellings in

order; and the glossy branches of holly, with their bright red berries,

began to appear at the windows. The scene brought to mind an old

writer's account of Christmas preparations:—"Now capons and hens,

besides turkeys, geese, and ducks, with beef and mutton—must all die;

for in twelve days a multitude of people will not be fed with a little.

Now plums and spice, sugar and honey, square it among pies and broth.

Now or never must[32] music be in tune, for the youth must dance and sing

to get them a heat, while the aged sit by the fire. The country maid

leaves half[33] her market, and must be sent again, if she forgets a pack

of cards on Christmas eve. Great is the contention of Holly and Ivy,

whether master or dame wears the breeches. Dice and cards benefit the

butler; and if the cook do not lack wit, he will sweetly lick his

fingers."

![The Country Maid The Country Maid]()

I was roused from this fit of luxurious meditation by a shout from my

little travelling companions. They had been looking out of the

coach-windows for the last few miles, recognising every tree and cottage

as they approached home, and now there was a general burst of

joy—"There's John! and there's old Carlo! and there's Bantam!" cried

the happy little rogues, clapping their hands.

At the end of a lane there was an old sober-looking servant in livery

waiting for them: he was accompanied by a superannuated pointer, and by

the redoubtable Bantam, a little old rat of a pony, with a shaggy mane

and long rusty tail, who stood dozing quietly by the roadside,[34] little

dreaming of the bustling times that awaited him.

I was pleased to see the fondness with which the little fellows leaped

about the steady old footman, and hugged the pointer, who wriggled his

whole body for joy. But Bantam was the great object of interest; all

wanted to mount at once; and it was with some difficulty that John

arranged that they should ride by turns, and the eldest should ride

first.

Off they set at last; one on the pony, with the dog bounding and barking

before him, and the[35] others holding John's hands; both talking at once,

and overpowering him by questions about home, and with school anecdotes.

I looked after them with a feeling in which I do not know whether

pleasure or melancholy predominated: for I was reminded of those days

when, like them, I had neither known care nor sorrow, and a holiday was

the summit of earthly felicity. We stopped a few moments afterwards to

water the horses, and on resuming our route, a turn of the road brought

us in sight of a neat country-seat. I could just distinguish the forms

of a lady and[36] two young girls in the portico, and I saw my little

comrades, with Bantam, Carlo, and old John, trooping along the carriage

road. I leaned out of the coach-window, in hopes of witnessing the happy

meeting, but a grove of trees shut it from my sight.

![A Neat Country Seat A Neat Country Seat]()

In the evening we reached a village where I had determined to pass the

night. As we drove into the great gateway of the inn, I saw on one side

the light of a rousing kitchen fire, beaming through a window. I

entered, and admired, for the hundredth time, that picture of

convenience, neatness, and broad honest enjoyment, the kitchen of an

English inn. It was of spacious dimensions, hung round with copper and

tin vessels highly polished, and decorated here and there with a

Christmas green. Hams, tongues, and flitches of bacon, were suspended

from the ceiling; a smoke-jack made its ceaseless clanking beside the

fireplace, and a clock ticked in one corner. A well-scoured deal table

extended along[37] one side of the kitchen, with a cold round of beef, and

other hearty viands upon it, over which two foaming tankards of ale

seemed mounting guard. Travellers of inferior order were preparing to[38]

attack this stout repast, while others sat smoking and gossiping over

their ale on two high-backed oaken seats beside the fire. Trim

housemaids were hurrying backwards and forwards under the directions of

a fresh, bustling landlady; but still seizing an occasional moment to

exchange a flippant word, and have a rallying laugh, with the group

round the fire. The scene completely realised Poor Robin's humble idea

of the comforts of mid-winter.

![Inn Kitchen Inn Kitchen]()

| Now trees their leafy hats do bare, |

| To reverence Winter's silver hair; |

| A handsome hostess, merry host, |

| A pot of ale now and a toast, |

| Tobacco and a good coal fire, |

| Are things this season doth require.

[41]

So intent were the servants upon their sports, that we had to ring

repeatedly before we could make ourselves heard. On our arrival being[54]

announced, the Squire came out to receive us, accompanied by his two

other sons; one a young officer in the army, home on leave of absence;

the other an Oxonian, just from the university. The Squire was a fine,

healthy-looking old gentleman, with silver hair curling lightly round an

open florid countenance; in which a physiognomist, with the advantage,

like myself, of a previous hint or two, might discover a singular

mixture of whim and benevolence.

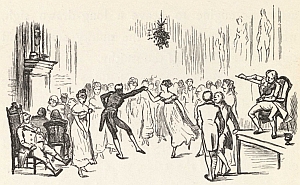

!["The company, which was assembled in a large old-fashioned hall."— "The company, which was assembled in a large old-fashioned hall."—]() "The company, which was assembled in a large old-fashioned hall."—page 54.

"The company, which was assembled in a large old-fashioned hall."—page 54.

The family meeting was warm and affectionate; as the evening was far

advanced, the Squire would not permit us to change our travelling

dresses, but ushered us at once to the company, which was assembled in a

large old-fashioned hall. It was composed of different branches of a

numerous family connection, where there were the usual proportion of old

uncles and aunts, comfortably married dames, superannuated spinsters,

blooming country cousins, half-fledged striplings, and bright-eyed

boarding-school hoydens.[55] They were variously occupied; some at a

round game of cards; others conversing around the fireplace; at one end

of the hall was a group of the young folks, some nearly grown up, others

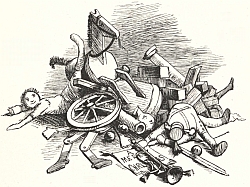

of a more tender and budding age, fully engrossed by a merry game; and a

profusion of wooden horses, penny trumpets, and tattered dolls, about

the floor, showed traces of a troop of little fairy beings, who having

frolicked through a happy day, had been carried off to slumber through a

peaceful night.

![Toys Toys]()

[56]

While the mutual greetings were going on between Bracebridge and his

relatives, I had time to scan the apartment. I have called it a hall,

for so it had certainly been in old times, and the Squire had evidently

endeavoured to restore it to something of its primitive state. Over the

heavy projecting fireplace was suspended a picture of a warrior in

armour, standing by a white horse, and on the opposite wall hung helmet,

buckler, and lance. At one end an enormous pair of antlers were inserted

in the wall, the branches serving as hooks on which to suspend hats,

whips, and spurs; and in the corners of the apartment were

fowling-pieces, fishing-rods, and other sporting implements. The

furniture was of the cumbrous workmanship of former days, though some

articles of modern convenience had been added, and the oaken floor had

been carpeted; so that the whole presented an odd mixture of parlour and

hall.

![The Yule Log The Yule Log]()

![The Squire in his Hereditary Chair The Squire in his Hereditary Chair]()

The grate had been removed from the wide[57] overwhelming fireplace, to

make way for a fire of wood, in the midst of which was an enormous log

glowing and blazing, and sending forth a vast volume of light and heat;

this I understood was the Yule-log, which the Squire was particular in[58]

having brought in and illumined on a Christmas eve, according to ancient

custom.

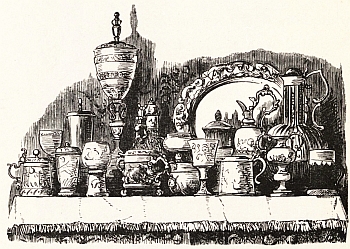

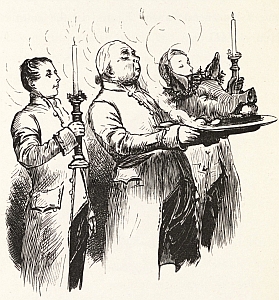

Supper was announced shortly after our arrival. It was served up in a

spacious oaken chamber, the panels of which shone with wax, and around

which were several family portraits decorated with holly and ivy. Beside

the accustomed lights, two great wax tapers, called Christmas candles,

wreathed with greens, were placed on a highly-polished buffet among the

family plate. The table was abundantly spread with substantial fare; but

the Squire made his supper of frumenty, a dish made of wheat cakes[60]

boiled in milk with rich spices, being a standing dish in old times for

Christmas eve. I was happy to find my old friend, minced-pie, in the

retinue of the feast; and finding him to be perfectly orthodox, and that

I need not be ashamed of my predilection, I greeted him with[61] all the

warmth wherewith we usually greet an old and very genteel acquaintance.

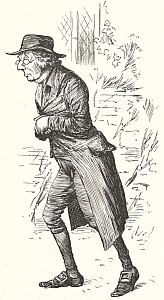

![Master Simon Master Simon]()

The mirth of the company was greatly promoted by the humours of an

eccentric personage whom Mr. Bracebridge always addressed with the

quaint appellation of Master Simon. He was a tight, brisk little man,

with the air of an arrant old bachelor. His nose was shaped like the

bill of a parrot; his face slightly pitted with the small-pox, with a

dry perpetual bloom on it, like a frost-bitten leaf in autumn. He had an

eye of great quickness and vivacity, with a drollery and lurking waggery

of expression that was irresistible. He was evidently the wit of the

family, dealing very much in[62] sly jokes and innuendoes with the ladies,

and making infinite merriment by harpings upon old themes; which,

unfortunately, my ignorance of the family chronicles did not permit me

to enjoy. It seemed to be his great delight during supper to keep a

young girl next him in a continual agony of stifled laughter, in spite

of her awe of the reproving looks of her mother, who sat opposite.

Indeed, he was the idol of the younger part of the company, who laughed

at everything he said or did, and at every turn of his countenance. I

could not wonder at it; for he must have been a miracle of

accom[63]plishments in their eyes. He could imitate Punch and Judy; make an

old woman of his hand, with the assistance of a burnt cork and

pocket-handkerchief; and cut an orange into such a ludicrous caricature,

that the young folks were ready to die with laughing.

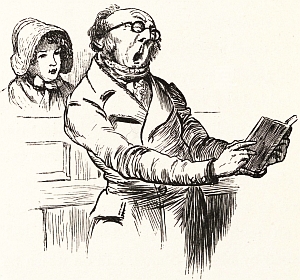

![Young Girl and Her Mother Young Girl and Her Mother]()

I was let briefly into his history by Frank Bracebridge. He was an old

bachelor of a small independent income, which by careful management was

sufficient for all his wants. He revolved through the family system like

a vagrant comet in its orbit; sometimes visiting one branch, and

sometimes another quite remote; as is often the case with gentlemen of

extensive connections and small fortunes in England. He had a chirping,

buoyant disposition, always enjoying the present moment; and his

frequent change of scene and company prevented his acquiring those rusty

unaccommodating habits with which old bachelors are so uncharitably

charged. He was a complete family chronicle, being versed in the

genealogy, history,[64] and intermarriages of the whole house of

Bracebridge, which made him a great favourite with the old folks; he was

a beau of all the elder ladies and superannuated spinsters, among whom

he was habitually considered rather a young fellow, and he was a master

of the revels among the children; so that there was not a more popular

being in the sphere in which he moved than Mr. Simon Bracebridge. Of

late years he had resided almost entirely with the Squire, to whom he

had become a factotum, and whom he particularly delighted by jumping

with his humour in respect to old times, and by having a scrap of an old

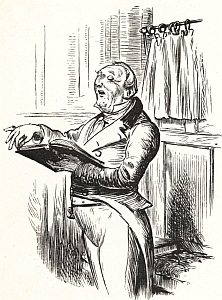

song to suit every occasion. We had presently a specimen of his

last-mentioned talent; for no sooner was supper removed, and spiced

wines and other beverages peculiar to the season introduced, than Master

Simon was called on for a good old Christmas song. He bethought himself

for a moment, and then, with a sparkle of the eye, and a voice that was

by no means bad,[65] excepting that it ran occasionally into a falsetto,

like the notes of a split reed, he quavered forth a quaint old ditty,—

| Now Christmas is come, |

| Let us beat up the drum, |

| And call all our neighbours together; |

| And when they appear, |

| Let us make them such cheer, |

| As will keep out the wind and the weather, etc. |

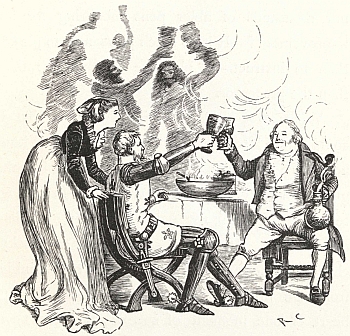

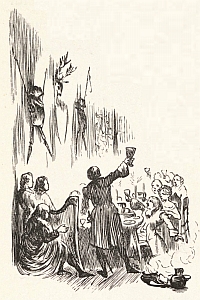

The supper had disposed every one to gaiety, and an old harper was

summoned from the [66] servants' hall, where he had been strumming all the

evening, and to all appearance comforting himself with some of the

Squire's home-brewed. He was a kind of hanger-on, I was told, of the

establishment, and though ostensibly a resident of the village, was

oftener to be found in the Squire's kitchen than his own home, the old

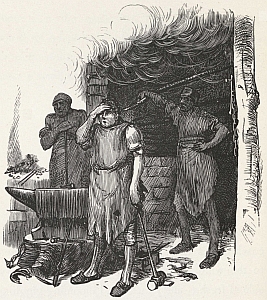

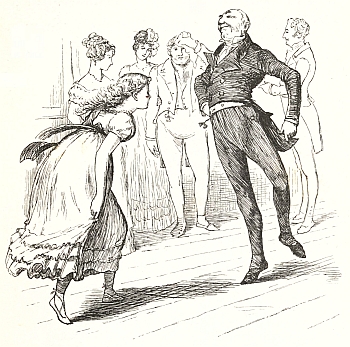

gentleman being fond of the sound of "harp in hall." The dance, like most dances after supper, was a merry one; some of the

older folks joined in it, and the Squire himself figured down several

couples with a partner with whom he affirmed he had danced at every

Christmas for nearly half-a-century. Master Simon, who seemed to be a

kind of connecting link between the old times and the new, and to be

withal a little antiquated in the taste of his accomplishments,

evidently piqued himself on his dancing, and was endeavouring to gain

credit by the heel and toe, rigadoon, and other graces of the ancient

school; but he had[67] unluckily assorted himself with a little romping

girl from boarding-school, who, by her wild vivacity, kept him

continually on the stretch, and defeated all his sober attempts at

elegance;—such are the ill-assorted matches to which antique gentlemen

are unfortunately prone!

[68]

![The Oxonian and his Maiden Aunt The Oxonian and his Maiden Aunt]()

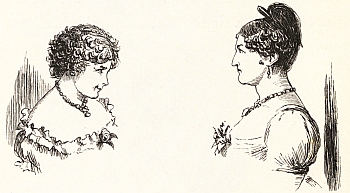

The young Oxonian, on the contrary, had led out one of his maiden aunts,

on whom the rogue played a thousand little knaveries with impunity; he

was full of practical jokes, and his delight was to tease his aunts and

cousins; yet, like all[69] madcap youngsters, he was a universal favourite

among the women. The most interesting couple in the dance was the young

officer and a ward of the Squire's, a beautiful blushing girl of

seventeen. From several shy glances which I had noticed in the course of

the evening, I suspected there was a little kindness growing up between

them; and, indeed, the young soldier was just the hero to captivate a

romantic girl. He was tall, slender, and handsome, and, like most young

British officers of late years, had picked up various small

accomplishments on the Continent—he could talk French and Italian—draw

landscapes, sing very tolerably—dance divinely; but, above all, he had

been wounded at Waterloo:—what girl of seventeen, well read in poetry

and romance, could resist such a mirror of chivalry and perfection!

![The Young Officer with his Guitar The Young Officer with his Guitar]()

The moment the dance was over, he caught up a guitar, and lolling

against the old marble fireplace, in an attitude which I am half

inclined[70] to suspect was studied, began the little French air of the

Troubadour. The Squire, however, exclaimed against having anything on

Christmas eve but good old English; upon which the young minstrel,

casting up his eye for a moment, as if in[71] an effort of memory, struck

into another strain, and, with a charming air of gallantry, gave

Herrick's "Night-Piece to Julia:"—

| Her eyes the glow-worm lend thee, |

| The shooting stars attend thee, |

| And the elves also, |

| Whose little eyes glow |

| Like the sparks of fire, befriend thee. |

No Will-o'-the-Wisp mislight thee; |

| Nor snake or glow-worm bite thee; |

| But on, on thy way, |

| Not making a stay, |

| Since ghost there is none to affright thee. |

Then let not the dark thee cumber; |

| What though the moon does slumber, |

| The stars of the night |

| Will lend thee their light, |

| Like tapers clear without number. |

Then, Julia, let me woo thee, |

| Thus, thus to come unto me; |

| And when I shall meet |

| Thy silvery feet, |

| My soul I'll pour into thee. |

The song might have been intended in com[72]pliment to the fair Julia, for

so I found his partner was called, or it might not; she, however, was

certainly unconscious of any such application, for she never looked at

the singer, but kept her eyes cast upon the floor. Her face was

suffused, it is true, with a beautiful blush, and there was a gentle

heaving of the bosom, but all that was doubtless caused by the exercise

of the dance; indeed, so great was her indifference, that she was

amusing herself with plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hothouse

flowers, and by the time the song was concluded, the nosehappy lay in

ruins on the floor.

The party now broke up for the night with the kind-hearted old custom of

shaking hands. As I passed through the hall, on the way to my chamber,

the dying embers of the Yule-clog still sent forth a dusky glow; and

had it not been the season when "no spirit dares stir abroad," I should

have been half tempted to steal from my room at midnight, and peep

whether the fairies might not be at their revels about the hearth.

!["Indeed, so great was her indifference, that she was amusing herself with plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hot-house flowers."—page 72. "Indeed, so great was her indifference, that she was amusing herself with plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hot-house flowers."—page 72.]() "Indeed, so great was her indifference, that she was amusing herself with plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hot-house flowers."—page 72.

"Indeed, so great was her indifference, that she was amusing herself with plucking to pieces a choice bouquet of hot-house flowers."—page 72.

[73]

My chamber was in the old part of the mansion, the ponderous furniture

of which might have been fabricated in the days of the giants. The room

was panelled with cornices of heavy carved-work, in which flowers and

grotesque faces were strangely intermingled; and a row of black-looking

portraits stared mournfully at me from the walls. The bed was of rich

though faded damask, with a lofty tester, and stood in a niche opposite

a bow-window. I had scarcely got into bed when a strain of music seemed

to break forth in the air just below the window. I listened, and found

it proceeded from a band, which I concluded to be the waits from some

neighbouring village. They went round the house, playing under the

windows. I drew aside the curtains, to hear them more distinctly. The

moonbeams fell through the upper part of the casement, partially

lighting up the antiquated apartment. The sounds, as they receded,

became more soft and aërial, and seemed to accord with quiet and

moonlight. I listened[74] and listened—they became more and more tender

and remote, and, as they gradually died away, my head sank upon the

pillow and I fell asleep.

![Asleep Asleep]()

Asleep [75]

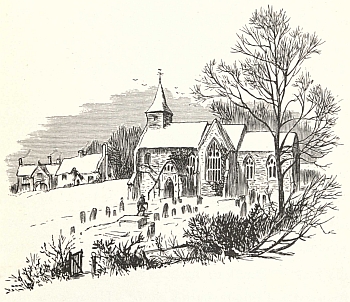

I have seldom known a sermon attended apparently with more immediate

effects; for on leaving the church the congregation seemed one and all

possessed with the gaiety of spirit so earnestly enjoined by their

pastor. The elder folks gathered in knots in the churchyard, greeting

and shaking hands; and the children ran about crying, Ule! Ule! and

repeating some uncouth[105] rhymes,

On our way homeward his heart seemed overflowing with generous and happy

feelings. As we passed over a rising ground which commanded something of

a prospect, the sounds of rustic merriment now and then reached our

ears; the Squire paused for a few moments, and looked around with an air

of inexpressible benignity. The beauty of the day was of itself

sufficient to[106] inspire philanthropy. Notwithstanding the frostiness of

the morning, the sun in his cloudless journey had acquired sufficient

power to melt away the thin covering of snow from every southern

declivity, and to bring out the living green which adorns an English

landscape even in mid-winter. Large tracts of smiling verdure contrasted

with the dazzling whiteness of the shaded slopes and hollows. Every

sheltered bank, on[107] which the broad rays rested, yielded its silver rill

of cold and limpid water, glittering through the dripping grass; and

sent up slight exhalations to contribute to the thin haze that hung just

above the surface of the earth. There was something truly cheering in

this triumph of warmth and verdure over the frosty thraldom of winter;

it was, as the Squire observed, an emblem of Christmas hospitality,

breaking through the chills of ceremony and selfishness, and thawing

every heart into a flow. He pointed with pleasure to the indications of

good cheer reeking from the chimneys of the comfortable farm-houses and

low thatched cottages. "I love," said he, "to see this day well kept by

rich and poor; it is a great thing to have one day in the year, at

least, when you are sure of being welcome wherever you go, and of

having, as it were, the world all thrown open to you; and I am almost

disposed to join with Poor Robin, in his malediction of every churlish

enemy to this honest festival:[108]—

| "Those who at Christmas do repine, |

| And would fain hence despatch him, |

| May they with old Duke Humphry dine, |

| Or else may Squire Ketch catch 'em." |

The Squire went on to lament the deplorable decay of the games and

amusements which were once prevalent at this season among the lower

orders, and countenanced by the higher: when the old halls of castles

and manor-houses were thrown open at daylight; when the tables were

covered with brawn, and beef, and humming ale; when the harp and the

carol resounded all day long, and when rich and poor were alike welcome

to enter and make merry.

"The nation," continued he, "is altered; we have almost lost our simple

true-hearted peasantry. They have broken asunder from the higher

classes, and seem to think their interests are separate. They have

become too knowing, and begin to read newspapers, listen to alehouse

politicians, and talk of reform. I think one mode to keep them in good

humour in these hard times[110] would be for the nobility and gentry to pass

more time on their estates, mingle more among the country people, and

set the merry old English games going again."

![The Poor at Home The Poor at Home]()

Such was the good Squire's project for mitigating public discontent;

and, indeed, he had once attempted to put his doctrine in practice, and

a few years before had kept open house during the holidays in the old

style. The country people, however, did not understand how to play their

parts in the scene of hospitality; many uncouth circumstances occurred;

the manor was overrun by all the vagrants of the country, and more

beggars drawn into the neighbourhood in one week than the parish

officers could get rid of in a year. Since then he had contented himself

with inviting the decent part of the neighbouring peasantry to call at

the hall on Christmas day, and distributing beef, and bread, and ale,

among the poor, that they might make merry in their own dwellings.[111]

We had not been long home when the sound of music was heard from a

distance. A band of country lads without coats, their shirt-sleeves

fancifully tied with ribands, their hats decorated with greens, and

clubs in their hands, were seen advancing up the avenue, followed by a

large number of villagers and peasantry. They stopped before the hall

door, where the music struck up a peculiar air, and the lads performed a

curious and intricate dance, advancing, retreating, and striking their

clubs together, keeping exact time[112] to the music; while one, whimsically

crowned with a fox's skin, the tail of which flaunted down his back,

kept capering round the skirts of the dance, and rattling a

Christmas-box with many antic gesticulations.

![Village Antics Village Antics]()

The Squire eyed this fanciful exhibition with great interest and

delight, and gave me a full account of its origin, which he traced to

the times when the Romans held possession of the island; plainly proving

that this was a lineal descendant of the sword-dance of the ancients.

"It was now," he said, "nearly extinct, but he had[113] accidentally met

with traces of it in the neighbourhood, and had encouraged its revival;

though, to tell the truth, it was too apt to be followed up by rough

cudgel-play and broken heads in the evening."

![Tasting the Squire's Ale Tasting the Squire's Ale]()

After the dance was concluded, the whole party was entertained with

brawn and beef, and stout home-brewed. The Squire himself mingled among

the rustics, and was received with awkward demonstrations of deference

and regard. It is true I perceived two or three of the younger peasants,

as they were raising their tankards to[114] their mouths when the Squire's

back was turned, making something of a grimace, and giving each other

the wink; but the moment they caught my eye they pulled grave faces, and

were exceedingly demure. With Master Simon, however, they all seemed

more at their ease. His varied occupations and amusements had made him

well known throughout the neighbourhood. He was a visitor at every

farm-house and cottage; gossiped with the farmers and their wives;

romped with their daughters; and, like that type of a vagrant bachelor,

the humble bee, tolled the sweets from all the rosy lips of the country

round.

![The Wit of the Village The Wit of the Village]()

The bashfulness of the guests soon gave way before good cheer and

affability. There is something genuine and affectionate in the gaiety of

the lower orders, when it is excited by the bounty and familiarity of

those above them; the warm glow of gratitude enters into their mirth,

and a kind word or a small pleasantry, frankly uttered by a patron,

gladdens the heart of the dependant more[115] than oil and wine. When the

Squire had retired the merriment increased, and there was much joking

and laughter, particularly between Master Simon and a hale, ruddy-faced,

white-headed farmer, who appeared to be the wit of the village; for I

observed all his companions to wait with open mouths for his retorts,

and burst into a gratuitous laugh before they could well understand

them.

The whole house indeed seemed abandoned to merriment. As I passed to my

room to dress for dinner, I heard the sound of music in a small court,

and, looking through a window that commanded it, I perceived a band of

wandering musicians, with pandean pipes and tambourine; a pretty

coquettish housemaid was dancing a jig[116] with a smart country lad, while

several of the other servants were looking on. In the midst of her sport

the girl caught a glimpse of my face at the window, and, colouring up,

ran off with an air of roguish affected confusion.

[117]

| |

"The old family mansion, partly thrown in deep shadow, and partly lit up by the cold moonshine"

"The old family mansion, partly thrown in deep shadow, and partly lit up by the cold moonshine"

Asleep

Asleep