« back

PRICE ONE SHILLING.

THE

BUTTERFLY'S BALL,

AND THE

GRASSHOPPER'S FEAST.

INTRODUCTION.

Early in the present century John Harris—one of the successors to the business of "Honest John Newbery," now carried on by Messrs Griffith & Farran at the old corner of St. Paul's Churchyard—began the publication of a series of little books, which for many years were probably among the most famous of the productions of the House. Now, however, according to the fate which usually overtakes books for children, nearly all of them are forgotten or unknown.

The first book in this series which was known as Harris's Cabinet was "The Butterfly's Ball," and was published in January 1807. This was followed in the same year by "The Peacock at Home" (a sequel to "The Butterfly's Ball"), "The Elephant's Ball," and "The Lion's Masquerade;" and then (prompted no doubt by the success of these, for we learn on the publisher's authority that of the two first 40,000 copies were sold within twelve months) Mr Harris brought out a torrent of little books of a like kind, of which the titles were: "The Lioness's Ball," "The Lobster's Voyage to the Brazils," "The Cat's Concert," "The Fishes' Grand Gala," "Madame Grimalkin's Party," "The Jackdaw's Home," "The Lion's Parliament," "The Water King's Lev�e;" and in 1809, by which time, naturally enough, the idea seems to have become quite threshed out and exhausted, the last of the Series was published; this was entitled, "The Three Wishes, or Think before you Speak."

Of this long list of books a few of the titles are still familiar, and one of them, "The Butterfly's Ball," may certainly claim to have become a Nursery Classic. It is still in regular demand; the edition now in sale being illustrated by Harrison Weir; it has been published in various forms, and has figured in most of the collections of prose and verse for the young that have been issued during this century. Probably to the minds of hundreds of people past middle age few lines are more familiar than the opening couplet—

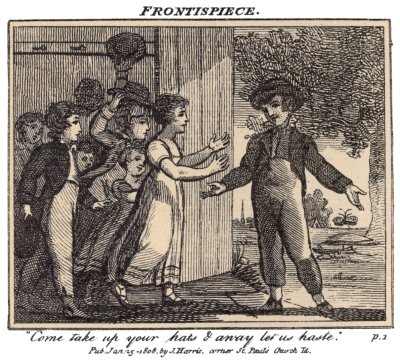

"Come take up your hats, and away let us haste

To the Butterfly's Ball and Grasshopper's Feast"—

and many no doubt by a little effort of memory could repeat the whole poem.

Hardly less famous were the three books which next followed in order of issue—"The Peacock at Home," "The Elephant's Ball," and "The Lion's Masquerade." Their original size was 5 by 4 inches, and they were issued in a simple printed paper wrapper. It is of these first four books that the reprint is here given, and in order to present both pictures and text with greater effect this reprint has been made upon considerably larger paper; the text and illustrations are fac-simile reproductions of originals from the celebrated Flaxman collection recently dispersed at a sale by Messrs Christie, Manson, & Woods, when Mr Tuer, to whom I am indebted for their loan, became their fortunate possessor. "The Butterfly's Ball" is not a reproduction of the first edition, which, as will be shown later on, would be considered by those who are familiar with the poem as incomplete. Moreover, the illustrations in the edition here presented are obviously by the same hand as that which embellished the other three books, and it was felt that for these reasons it would possess a greater interest.

"The Butterfly's Ball" first appeared in the November number of the Gentleman's Magazine, where it is said to have been written by William Roscoe—M.P. for Liverpool, the author of "The Life of Leo X.," and well known in the literary circles of his day—for the use of his children, and set to music by order of their Majesties for the Princess Mary. When the verses were subsequently published in book form, the text and pictures were engraved together on copperplates. An edition, with pictures on separate pages, appeared early in the next year, which is the one here reproduced.

In this edition there are many variations from the previous one. The allusions to "little Robert"—evidently William Roscoe's son—do not occur in the former, and many slight improvements, tending to make the verses more rhythmical and flowing, are introduced. The whole passage, "Then close on his haunches" (p. 7) to "Chirp his own praises the rest of the night," &c. (p. 10), is an interpolation in this later edition. It is, I believe, certain that the verses were written by Roscoe for his children on the occasion of the birthday of his son Robert, who was nearly the youngest of his seven sons. No doubt when they were copied out for setting to music the allusions to his own family were omitted by the author. A correspondent of Notes and Queries—who is, I believe, a niece of the late Sir George Smart—says, in reference to the question of the setting of the verses to music, that—

"The MS., in Roscoe's own handwriting, as sent to Sir G. Smart for setting to music, is in a valuable collection of autographs bequeathed by the musician to his daughter. The glee was written for the three princesses—Elizabeth, Augusta, and Mary—daughters of George III, and pupils of Sir George, and was performed by them during one of their usual visits to Weymouth."

"The Peacock at Home" and "The Lion's Masquerade" were, as the title-page puts it, written "by a Lady," and we should most likely have remained in ignorance as to who the lady was if there had not been published in 1816 another little book of a somewhat similar character, entitled "The Peacock and Parrot on their Tour to discover the Author of 'The Peacock at Home,'" which, the Preface tells us, was written immediately after the appearance of "The Peacock at Home," but from various circumstances was laid aside. "In the opinion of the publishers," the Preface goes on to say, "it is so nearly allied in point of merit to that celebrated trifle that it is introduced at this late period."

The book relates in verse how the peacock and parrot—

"... far as England extends

Then together did travel to visit their friends,

Endeavour to find out the name of our poet,

And ere we return ten to one that we know it."

After long travelling—

"A path strewed with flowers they gaily pursued,

And in fancy their long-sought Incognita viewed.

Till all their cares over in Dorset they found her,

And plucking a wreath of green bay-leaves they crowned her."

In a footnote is added, "Mrs Dorset was the authoress of 'The Peacock at Home.'"

Mrs Dorset, according to a note by Mr Dyce which appears on the fly-leaf of a copy of "The Peacock at Home," in the Dyce and Forster Collection at South Kensington, was sister to Charlotte Smith. Their maiden name was Turner.

The British Museum Catalogue says Mrs Dorset also wrote "The Three Wishes, or Think before you Speak," which is the last on the list of books in Harris's Cabinet. (See p. iv.)

It seems to be clear that the same lady wrote "The Lion's Masquerade" as "The Peacock at Home," for in "The Lioness's Ball" (a companion to "The Lion's Masquerade") the dedication begins thus—

"I do not, fair Dorset, I do not aspire,

With notes so unhallowed as mine,

To touch the sweet strings of thy beautiful lyre,

Or covet the praise that is thine."

I regret that I am unable to offer any conjecture here as to the "W. B." who wrote "The Elephant's Ball:" the same initials appear to an appendix to an edition of "Goody Two Shoes," published some time before 1780, but this may be a coincidence only.

Besides the interest and merit of these little books on literary grounds, these earlier editions are especially noteworthy because they were illustrated by the painter William Mulready, and the drawings he made for them are amongst the earliest efforts of his genius: they were executed before he had reached man's estate. It is not a little curious to observe in this connection how many artists who have risen to eminence have at the outset of their career been employed in illustrating books for children; it would indeed appear that until comparatively recent years the veriest tiro was considered capable of furnishing the necessary embellishments for books for the nursery—a state of things which, we need not say, happily does not obtain in the present day. Notwithstanding this, however, these and many other little books of a bygone time abound in instructive indications of the beginnings of genius which has subsequently delighted the world with its masterpieces.

In connection with Mulready and children's books it may be interesting to note that in 1806 a little book called "The Looking Glass" was published, said to be written by William Godwin under the name of "Theophilus Markliffe." This work is the history and early adventures of a young artist, and it is known that it was compiled from a conversation with Mulready, who was then engaged in illustrating some juvenile books for the author, and the facts in it relate to the painter's early life. It contains illustrations of the talent of the subject done at three, five, and six years old, which are presumed to be imitations of Mulready's own drawings at the same ages.

I cannot more fitly close these few words of Introduction than by quoting the quaint and curious announcement with which Mr Harris was wont to commend these little books to the public. "It is unnecessary," says he, "for the publisher to say anything more of these little productions than that they have been purchased with avidity and read with satisfaction by persons in all ranks of life." No doubt the public of to-day will be curious to see what manner of book it was that was so eagerly sought after by the children of the early days of the present century, and interested in comparing it with the more finished but often showy and sensational productions of our own time.

C. W.

Leytonstone,

September 1883.

THE

BUTTERFLY'S BALL,

AND THE

GRASSHOPPER'S FEAST.

By Mr. ROSCOE.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR J. HARRIS, SUCCESSOR TO E. NEWBERY,

AT THE ORIGINAL JUVENILE LIBRARY, CORNER

OF ST. PAUL'S CHURCH-YARD.

1808.

Field & Tuer, Ye Leadenhalle Presse, London.

THE

BUTTERFLY'S BALL.

Come take up your Hats, and away let us haste

To the Butterfly's Ball, and the Grasshopper's Feast.

The Trumpeter, Gad-fly, has summon'd the Crew,

And the Revels are now only waiting for you.

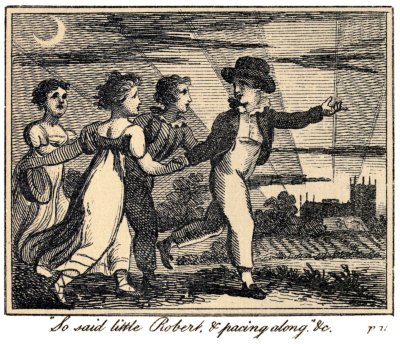

So said little Robert, and pacing along,

His merry Companions came forth in a Throng.

And on the smooth Grass, by the side of a Wood,

Beneath a broad Oak that for Ages had stood,

Saw the Children of Earth, and the Tenants of Air,

For an Evening's Amusement together repair.

And there came the Beetle, so blind and so black,

Who carried the Emmet, his Friend, on his Back.

And there was the Gnat and the Dragon-fly too,

With all their Relations, Green, Orange, and Blue.

And there came the Moth, with his Plumage of Down,

And the Hornet in Jacket of Yellow and Brown;

Who with him the Wasp, his Companion, did bring,

But they promis'd, that Evening, to lay by their Sting.

And the sly little Dormouse crept out of his Hole,

And brought to the Feast his blind Brother, the Mole.

And the Snail, with his Horns peeping out of his Shell,

Came from a great Distance, the Length of an Ell.

A Mushroom their Table, and on it was laid

A Water-dock Leaf, which a Table-cloth made.

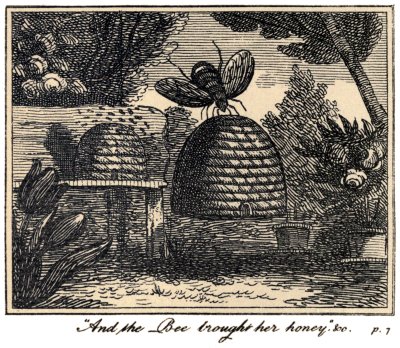

The Viands were various, to each of their Taste,

And the Bee brought her Honey to crown the Repast.

Then close on his Haunches, so solemn and wise,

The Frog from a Corner, look'd up to the Skies.

And the Squirrel well pleas'd such Diversions to see,

Mounted high over Head, and look'd down from a Tree.

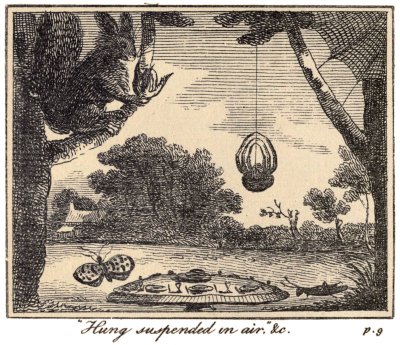

Then out came the Spider, with Finger so fine,

To shew his Dexterity on the tight Line.

From one Branch to another, his Cobwebs he slung,

Then quick as an Arrow he darted along,

But just in the Middle,—Oh! shocking to tell,

From his Rope, in an Instant, poor Harlequin fell.

Yet he touch'd not the Ground, but with Talons outspread,

Hung suspended in Air, at the End of a Thread.

Then the Grasshopper came with a Jerk and a Spring,

Very long was his Leg, though but short was his Wing;

He took but three Leaps, and was soon out of Sight,

Then chirp'd his own Praises the rest of the Night.

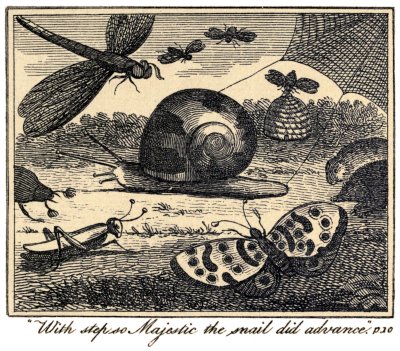

With Step so majestic the Snail did advance,

And promis'd the Gazers a Minuet to dance.

But they all laugh'd so loud that he pull'd in his Head,

And went in his own little Chamber to Bed.

Then, as Evening gave Way to the Shadows of Night,

Their Watchman, the Glow-worm, came out with a Light.

Then Home let us hasten, while yet we can see,

For no Watchman is waiting for you and for me,

So said little Robert, and pacing along,

His merry Companions returned in a Throng.

END OF THE BUTTERFLY'S BALL.