« back

STEVE AND THE STEAM ENGINE

By Sara Ware Bassett

The Invention Series

Paul and the Printing Press

Steve and the Steam Engine

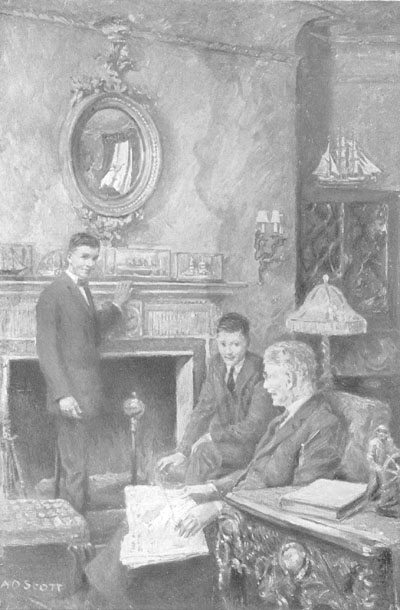

"It was the conquering of this multitude of defects that gave to the world the intricate, exquisitely made machine."—Frontispiece. See page 103.

|

The Invention Series STEVE AND THE STEAM ENGINE BY SARA WARE BASSETT WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY A. O. SCOTT BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY 1921 |

Copyright, 1921,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published September, 1921

THE PLIMPTON PRESS

NORWOOD · MASS · U · S · A

Contents

| I | AN UNPREMEDITATED FOLLY | 1 | |

| II | A MEETING WITH AN OLD FRIEND | 19 | |

| III | A SECOND CALAMITY | 34 | |

| IV | THE STORY OF THE FIRST RAILROAD | 51 | |

| V | STEVE LEARNS A SAD LESSON | 67 | |

| VI | MR. TOLMAN'S SECOND YARN | 77 | |

| VII | A HOLIDAY JOURNEY | 94 | |

| VIII | NEW YORK AND WHAT HAPPENED THERE | 110 | |

| IX | AN ASTOUNDING CALAMITY | 125 | |

| X | AN EVENING OF ADVENTURE | 145 | |

| XI | THE CROSSING OF THE COUNTRY | 156 | |

| XII | NEW PROBLEMS | 169 | |

| XIII | DICK MAKES HIS SECOND APPEARANCE | 178 | |

| XIV | A STEAMBOAT TRIP BY RAIL | 192 | |

| XV | THE ROMANCE OF THE CLIPPER SHIP | 205 | |

| XVI | AGAIN THE MAGIC DOOR OPENS | 216 | |

| XVII | MORE STEAMBOATING | 224 | |

| XVIII | A THANKSGIVING TRAGEDY | 238 | |

| XIX | THE END OF THE HOUSE PARTY | 248 |

Illustrations

| "It was the conquering of this multitude of defects that gave to the world the intricate, exquisitely made machine."—Frontispiece. | Frontispiece |

| "You've got your engine nicely warmed up, youngster," he observed casually. | 8 |

| "I wish you'd tell me about this queer little old-fashioned boat." | 180 |

| He was fighting to prevent himself from being drawn beneath the jagged, crumbling edge of the hole. | 244 |

STEVE AND THE STEAM ENGINE

Steve Tolman had done a wrong thing and he knew it.

While his father, mother, and sister Doris had been absent in New York for a week-end visit and Havens, the chauffeur, was ill at the hospital, the boy had taken the big six-cylinder car from the garage without anybody's permission and carried a crowd of his friends to Torrington to a football game. And that was not the worst of it, either. At the foot of the long hill leading into the village the mighty leviathan so unceremoniously borrowed had come to a halt, refusing to move another inch, and Stephen now sat helplessly in it, awaiting the aid his comrades had promised to send back from the town.

What an ignominious climax to what had promised to be a royal holiday! Steve scowled with chagrin and disappointment.

The catastrophe served him right. Unquestionably he should not have taken the car without asking. He had never run it all by himself before, although many times he had driven it when either his father or Havens had been at his elbow. It had gone all right then. What reason had he to suppose a mishap would befall him when they were not by? It was infernally hard luck!

Goodness only knew what was the matter with the thing. Probably something was smashed, something that might require days or even weeks to repair, and would cost a lot of money. Here was a pretty dilemma!

How angry his father would be!

The family were going to use the automobile Saturday to take Doris back to Northampton for the opening of college and had planned to make quite a holiday of the trip. Now it would all have to be given up and everybody would blame him for the disappointment. A wretched hole he was in!

The boys had not given him much sympathy, either. They had been ready enough to egg him on into wrong-doing and had made of the adventure the jolliest lark imaginable; but the moment fun had been transformed into calamity they had deserted him with incredible speed, climbing out of the spacious tonneau and trooping jauntily off on foot to see the town. It was easy enough for them to wash their hands of the affair and leave him to the solitude of the roadside; the automobile was not theirs and when they got home they would not be confronted by irate parents.

How persuasively, reflected Stephen, they had urged him on.

"Oh, be a sport, Steve!" Jack Curtis had coaxed. "Who's going to be the wiser if you do take the car? Anyhow, you have run it before, haven't you? I don't believe your father will mind."

"Take a chance, Stevie," his chum, Bud Taylor, pleaded. "What's the good of being such a boob? Do you think if my father had a car and it was standing idle in the garage when a bunch of kids needed it to go to a school game I would hesitate? You bet I wouldn't!"

"It isn't likely your Dad would balk at your using the car if he knew the circumstances," piped another boy. "We have got that match to play off, and now that the electric cars are held up by the strike how are we to get to Torrington? Don't be a ninny, Steve."

Thus they had ridiculed, cajoled, and wheedled Steve until his conscience had been overpowered and, yielding to their arguments, he had set forth for the adjoining village with the triumphant throng of tempters. At first all had gone well. The fourteen miles had slipped past with such smoothness and rapidity that Stephen, proudly enthroned at the wheel, had almost forgotten that any shadow rested on the hilarity of the day. He had been dubbed a good fellow, a true sport, a benefactor to the school—every complimentary pseudonym imaginable—and had glowed with pleasure beneath the avalanche of flattery. As the big car with its rollicking occupants had spun along the highway, many a passer-by had caught the merry mood of the cheering group and waved a smiling salutation in response to their shouts.

In the meanwhile, exhilarated by the novelty of the escapade, Steve had increased the speed until the red car fairly shot over the level macadam, its blurred outlines lost in the scarlet of the autumn foliage. Then suddenly when the last half-mile was reached and Torrington village, the goal of the pilgrimage, was in sight, quite without warning the panting monster had stopped and all attempts to urge it farther were of no avail. There it stood, its motionless engine sending out odors of hot varnish and little shimmering waves of heat.

Immediately a hush had descended upon the boisterous company. There was a momentary pause, followed by a clamor of advice. When, however, it became evident that there was no prospect of restoring the disabled machine to action, one after another of the frightened schoolboys had dropped out over the sides of the car and after loitering an instant or two with a sort of shamefaced indecision, at the suggestion of Bud Taylor they had all set out for the town.

"Tough luck, old chap!" Bud had called over his shoulder. "Mighty tough luck! Wish we had time to wait and see what's queered the thing; but the game is called at two-thirty, you know, and we have only about time to make it. We'll try and hunt up a garage and send somebody back to help you. So long!"

And away they had trooped without so much as a backward glance, leaving Stephen alone on the country road, worried, mortified, and resentful. There was no excuse for their heartless conduct, he fumed indignantly. They were not all on the eleven. Five of the team had come over in Tim Barclay's Ford, so that several of the fellows Steve had brought were merely to be spectators of the game. At least Bud Taylor, his especial crony, was not playing. He might have remained behind. How selfish people were, and what a fleeting thing was popularity! Why, half an hour ago he had been the idol of the crowd! Then Bud had shouted: "Come ahead, kids, let's hoof it to Torrington!" and in the twinkling of an eye the tide had turned, the mob had shifted its allegiance and gone tagging off at the heels of a new leader. They did not mean to have their pleasure spoiled, not they!

Scornfully Stephen watched them mount the hill, their crimson sweaters making a zigzag line of color in the sunshine; even their laughter, care-free as if nothing had happened, floated back to him on the still air, demonstrating how little concern they felt for him and his refractory automobile. Well might they proceed light-heartedly to the village, spend their money on sodas and ice-cream cones, and shout themselves hoarse at the game. No thought of future punishment marred their enjoyment and the program was precisely the one he had outlined for himself before Fate had intervened and raised a prohibitory hand.

The fun he had missed was, however, of scant consequence now. All he asked was to get the car safely back to his father's garage before the family returned from New York on the afternoon train. Now that his excitement had cooled into sober second thought, he marveled that he had been led into committing such a monstrous offense. He must have been mad. Often he had begged to do the very thing he had done and his father had always refused to let him, insisting that an expensive touring car was no toy for a boy of his age. Perhaps there had been some truth in the assertion, too, he now admitted. Yet were he to hang for it, he could not see why he had not run the car exactly as his elders were wont to do. Of course he had had a pretty big crowd aboard and the heavy load might have strained the machinery; and possibly—just possibly—he had speeded a bit. He certainly had made phenomenally good time for he did not want the fellows to think he was afraid to let out the engine.

Well, whatever the matter was, the harm was done now and he was in a most unenviable plight. No doubt it would cost a small fortune to get the automobile into shape again, more money than he had in the world; certainly far more than he had in his pocket at the present moment. What was he to do? Even suppose the boys did remember to send back help (they probably wouldn't—but suppose they did) how was he to pay a machinist? As he pictured himself being towed to a garage and the car being left there, he felt an uncomfortable sensation in his throat. He certainly was in for it now.

It would be ignominious to charge the repairs to his father but that would be the only course left him. Fortunately Mr. Tolman, who was a railroad official, was well known in the locality and therefore there would be no trouble about obtaining credit; but to ask his father to pay the bills for this escapade was anything but a manly and honorable way out and Steve wished with all his heart he had never been persuaded into the wretched affair. If there were only some escape possible, some alternative from being obliged to confess his wrong-doing! But to hope to conceal or make good the disaster was futile. And even if he could cover up what had happened, how contemptible it would be! He detested doing anything underhanded. Only sneaks and cowards resorted to subterfuge and although he had been called many names in his life these two had not been among them.

No, he should make a clean breast of what he had done and bear the consequences, and once out of his miserable plight he would take care never again to be a party to such an adventure. He had learned his lesson.

So absorbed was he in framing these worthy resolutions that he did not notice a tiny moving speck that appeared above the crest of the hill and now came whirling toward him. In fact the dusty truck and its yet more dusty driver were beside him before he heeded either one. Then the newcomer came to a stop and he heard a pleasant voice:

"What's the matter, sonny?"

Stephen glanced up, trying bravely to return his questioner's smile.

The man who addressed him was white-haired, ruddy, and muscular, and he wore brown denim overalls stained with oil and grease; but although he was middle-aged there was a boyish friendliness in his face and in the frank blue eyes that peered out from under his shaggy brows.

"What's the trouble with your machine?" he repeated.

"I don't know," returned Stephen. "If I did, you bet I wouldn't be sitting here."

The workman laughed.

"Suppose you let me have a look at it," said he, climbing off the seat on which he was perched.

"I wish you would."

"It is a pretty fine car, isn't it?" observed the man, as he approached it. "Is it yours?"

"My father's."

"He lets you use it, eh?"

Stephen did not answer.

"Some fathers ain't that generous," went on the man as he began to examine the silent monster. "If I had an outfit like this, I ain't so sure I'd trust it to a chap of your size. Still, if you have your license, I suppose you must know how to run it."

A shiver passed through Stephen's body. A license! What if the stranger should ask to see it?

There was a heavy fine, he now remembered, for driving a car unless one were in possession of this precious paper, although what the penalty was he could not at the instant recall; he had entirely forgotten there were any such legal details. Fearfully he eyed the mechanic.

The man, however, did not pursue the subject but instead appeared engrossed in carefully inspecting the automobile inside and out. As he poked about, now here, now there, Stephen watched him with constantly increasing nervousness; and after the investigation had proceeded for some little time and no satisfactory result had been reached, the boy's heart sank. Something very serious must be the matter if the trouble were so hard to locate, he reasoned. In imagination he heard his father's indignant reprimands and saw the Northampton trip shrivel into nothingness.

The workman in the meantime remained silent, offering no comment to relieve his anxiety. What he was thinking under the shabby visor cap pulled so low over his brows it was impossible to fathom. His hand was now unscrewing the top of the gasoline tank.

"You've got your engine nicely warmed up, youngster," observed he casually. "Maybe 'twas just as well you did come to a stop. You must have covered the ground at a pretty good clip."

There certainly was something very disconcerting about the stranger's conversation and again Stephen looked at him with suspicion.

"Oh, I don't know," he mumbled, trying to assume an off-hand air. "Perhaps we did come along fairly fast."

"You weren't alone then."

"N—o," was the uncomfortable reply. "The fellows who sent you back from the village were with me."

For the first time the workman evinced surprise.

"Nobody sent me," he retorted. "I just thought as I was going by that you looked as if you were up against it, and as I happen to know something about engines I pulled up to give you a helping hand. The fix you are in isn't serious, though." He smiled broadly as if something amused him.

"What is the matter with the car?" demanded the boy desperately, in a voice that trembled with eagerness and anxiety and defied all efforts to remain under his control.

"Why, son, nothing is wrong with your car. You've got no gasoline, that's all."

"Gasoline!" repeated the lad blankly.

"Sure! You couldn't have had much aboard when you started, I guess. It managed to bring you as far as this, however, and here you came to a stop. The up-grade of the hill tipped the little gas you did have back in the tank so it would not run out, you see. Fill her up again and she'll sprint along as nicely as ever."

The relief that came with the information almost bowled Steve over.

For a moment he could not speak; then when he had caught his breath he exclaimed excitedly:

"How can I get some gasoline?"

His rescuer laughed at the fevered question.

"Why, I happen to have a can of it here on my truck," he drawled, "and I can let you have part of it if you are so minded."

"Oh, I don't want to take yours," objected the boy.

"Nonsense! Why not? I am going right past a garage on my way back and can get plenty more. We'll tip enough of mine into your tank to carry you home. It won't take a minute."

The suggestion was like water to the thirsty.

"All right!" cried Stephen. "If you will let me pay for it I shall be mightily obliged to you. I'm mightily obliged anyway."

"Pshaw! I've done nothing," protested the person in the oily jumper. "What are we in the world for if not to do one another a good turn when we can?"

As he spoke he extricated from his conglomerate load of lumber, tools, and boxes a battered can, the contents of which he began to transfer into Stephen's empty tank.

"There!" ejaculated he presently, as he screwed the metal top on. "That isn't all she'll hold, but it will at least get you home. You are going right back, aren't you?"

The boy glanced quickly at the speaker.

"Yes."

"That's right. I would if I were in your place," urged the man.

Furtively Stephen scrutinized the countenance opposite but although the words had contained a mingled caution and rebuke there was not the slightest trace of interest in the face of the speaker, who was imperturbably wiping off the moist nickel cap with a handful of waste from his pocket.

"Yes," he repeated half-absently, "I take it that amount of gas will just about carry you back to Coventry; it won't allow for any detours, to be sure, but if you follow the straight road it ought to fetch you up there all right."

Stephen started and again an interrogation rose to his lips. Who was this mysterious mechanic and why should he assume with such certainty that Coventry was the abiding place of the car? He longed to ask but a fear of lengthening the interview prevented him from doing so. If he began to ask questions might not the stranger assume the same privilege and wheel upon him with some embarrassing inquiry? No, the sooner he was clear of this wizard in the brown overalls the better. But for the sake of his peace of mind he should like to know whether the man really knew who he was or whether his comments were simply matters of chance. There certainly was something very uncanny and uncomfortable about it all, something that led him to feel that the person in the jumper was fully acquainted with his escapade, disapproved of it, and meant to prevent him from prolonging it. Yet as he took a peep into the kindly blue eyes which he did not trust himself to meet directly he wondered if this assumption were not created by a guilty conscience rather than by fact. Certainly there was nothing accusatory in the other's bearing. His face was frankness itself. In books criminals were always fearing that people suspected them, reflected Steve. The man knew nothing about him at all. It was absurd to think he did.

Nevertheless the boy was eager to be gone from the presence of those searching blue eyes and therefore he climbed into his car, murmuring hurriedly:

"You've been corking to help me out!"

The workman held up a protesting hand.

"Don't think of it again," he answered. "I was glad to do it. Good luck to you!"

With nervous hands Stephen started the engine and, backing the automobile about, headed it homeward. Now that danger was past his desire to reach Coventry before his father should arrive drove every other thought from his mind, and soon the mysterious hero of the brown jumper was forgotten. Although he made wonderfully good time back over the road it seemed hours before he turned in at his own gate and brought the throbbing motor to rest in the garage. A sigh of thankfulness welled up within him. The great red leviathan that had caused him such anguish of spirit stood there in the stillness as peacefully as if it had never stirred from the spot it occupied. If only it had remained there, how glad the boy would have been.

He ventured to look toward the windows fronting the avenue. No one was in sight, it was true; but to flatter himself that he had been unobserved was ridiculous for he saw by the clock that his father, mother, and Doris must already have reached home. Doubtless they were in the house now and fully acquainted with what he had done. If they had not missed the car from the garage they would at least have seen it whirl into the driveway with him at the wheel. Any moment his father might appear at his shoulder. To delay was useless. He had had his fun and now in manly fashion he must face the music and pay for it. How he dreaded the coming storm!

Once, twice he braced himself, then moved reluctantly toward the house, climbed the steps, and let himself in at the front door. He could hardly expect any one would come to greet him under the circumstances. An ominous silence pervaded the great dim hall but after the glare of the white ribbon of road on which his eyes had been so intently fixed he found the darkness cool and tranquilizing. At first he could scarcely see; then as he gradually became accustomed to the faint light he espied on the silver card tray a telegram addressed to himself and with a quiver of apprehension tore it open. Telegrams were not such a common occurrence in his life that he had ceased to regard them with misgiving.

The message on which his gaze rested, however, contained no ill tidings. On the contrary it merely announced that the family had been detained in New York longer than they had expected and would not return until noon to-morrow. He would have almost another day, therefore, before he would be forced to make confession to his father! The respite was a welcome one and with it his tenseness relaxed. He even gained courage on the strength of his steadier nerves to creep into the kitchen and confront Mary, the cook, whom he knew must have seen him shoot into the driveway and who, having been years in the home, would not hesitate to lecture him roundly for his conduct. But Mary was not there and neither was Julia, the waitress. In the absence of the head of the house the two had evidently ascended to the third story there to forget in sleep the cares of daily life. Stephen smiled at the discovery. It was a coincidence. Unquestionably Fate was with him. It helped his self-respect to feel that at least the servants were in ignorance of what he had done. Nobody knew—nobody at all!

With an interval of rest and a dash of cold water upon his face gradually the act he had committed began to sink back into normal perspective and loom less gigantic in his memory. After all was it such a dreadful thing, he asked himself. Of course he should not have done it and he fully intended to confess his fault and accept the blame. But was the folly so terrible? He owned that he regretted it and admitted that he was somewhat troubled over the probable consequences, and every time he awoke in the night a dread of the morrow came upon him. In the morning he rushed off to school, found the team had won the game, and came home feeling even more justified than before. Why, if he had not taken the car, the school might have forfeited that victory!

All the afternoon as he sat quietly at his books he tried to keep this consideration uppermost in his mind. Then at dinner time there was a stir in the hall and he knew the moment he feared had arrived. The family were back again! Slowly he stole down over the heavily carpeted stairs. Yes, there they were, just coming in at the door, laughing and chatting gaily with Julia, who had let them in. The next instant his mother had espied him on the landing and had called a greeting.

There was a smile on her face that reproached him for having yielded to the temptation to deceive her even for a second.

"Such a delightful trip as we have had, Steve!" she called. "We wished a dozen times that you were with us. But some vacation you shall have a holiday in New York with your father to pay for what you have missed this time. You shall not be cheated out of all the fun, dear boy!"

"Everything been all right here, son?" inquired his father from the foot of the stairs.

"Yes, Dad."

"Havens has not showed up yet, I suppose."

The boy flushed.

"No, sir."

"It seems to take him an interminable time to have his tonsils out. If he does not appear pretty soon I shall have to get another man to run the car. We can't be left high and dry like this," fretted the elder man irritably. "Suppose I knew nothing about it, where would we be? I wished to-day you were old enough to have a license and could have come to the station to meet us. I believe with a little more instruction you could manage that automobile all right. Not that I should let you go racing over the country with a lot of boys. But you might be very useful in taking your mother and sister about and helping when we were in a fix like this. I think you would enjoy doing it, too."

"I—I'm—sure I should," replied the lad, avoiding his father's eye and studying the toe of his shoe intently. It passed through his mind as he stood there that now was the moment for confession. He had only to say,

"I had the car out yesterday," and the dreaded ordeal would be over. But somehow he could not utter the words. Instead he descended from the landing and followed the others into the library where the conversation immediately shifted to other topics. In the jumble of narrative his chance to speak was swallowed up nor during the next few days did any suitable opportunity occur for him to make his belated confession. When Mr. Tolman was not at meetings of the railroad board he was at his office or occupied with important affairs, and by and by so many events had intervened that to go back into the past seemed to Stephen idle sentimentality. At length he had lulled his conscience into deciding that in view of the conditions it was quite unnecessary to acquaint his father and mother with his wrong-doing at all. He was safely out of the entanglement and was it not just as well to accept his escape with gratitude and let sleeping dogs lie? All the punishments in the world could not change anything now. What would be the use of telling?

The day of the excursion to Northampton was one of those clear mornings when a light frost turned the maples to vermilion and in a single night transformed the ripening summer foliage to the splendor of autumn. The Tolman family were in the highest spirits; it was not often that Mr. Tolman could be persuaded to leave his business and steal away for a week-end and when he did it was always a cause for great rejoicing. Doris, elated at the prospect of rejoining her college friends, was also in the happiest frame of mind and tripped up and down stairs, collecting her forgotten possessions and jamming them into her already bulging suitcase.

As for Steve, the prickings of conscience that had at first tormented him and made him shrink from being left alone with his father had quite vanished. He had argued himself into a state of mental tranquility where further punishment for his misdemeanor seemed superfluous. After his hairbreadth escape from disaster there was no danger, he argued, of his repeating the experiment, and was not this the very lesson all punishments sought to instill? If he had achieved this result without bothering his father about the details, why so much the better. Did not the old adage say that "experience is the best teacher"? Certainly in this case the maxim held true.

Having thus excused his under-handedness and stifled the protests of his better nature he felt, or tried to feel, entirely at peace with the world; and as he now sauntered out to greet the new day he did it as jauntily as if he had nothing to conceal. Already the car was at the door with the luggage aboard and its engine humming invitingly. As the boy listened to the sound he could not but rejoice that the purring monster could tell no tales. How disconcerting it would be should the scarlet devil suddenly shout aloud: "Well, Steve, don't you hope we do not get stalled to-day the way we did going to Torrington?" Mercifully there was no danger of that. The engine might puff and purr and snort but at least it could not talk, and his secret was quite safe. This reflection lighted his face with courage and when the family came out to join him no one would have suspected that the slender boy waiting on the doorstep harbored a thought of anything but anticipation in the prospect of the coming holiday.

"Is everything in, Steve?" asked his father, approaching with Doris's remaining grip.

"I think so, Dad," was the reply. "It certainly seems as if I had piled in almost a dozen suitcases."

"Nonsense, Stevie," pouted Doris. "There were only four."

"Five, Miss Sophomore!" contradicted her brother. "Five! That one Dad is bringing makes the fifth, and I would be willing to bet that it is yours."

"That's where you are wrong, Smartie," the girl laughed good-humoredly, making a mischievous grimace at him from beneath the brim of her saucy little toque of blue velvet. "I am not guilty of the extra suitcase. It's mother's."

"Your mother's!" ejaculated Mr. Tolman incredulously. "Mercy on us! I never knew your mother to be starting out on a short trip with such an array of gowns." Then turning toward his wife, he added in bantering fashion: "Aren't you getting a little frivolous, my dear? If it were Doris now—"

"But it isn't this time!" interrupted the young lady triumphantly.

Her mother exchanged a glance with her and they both laughed.

"No, Henry, I am the one to blame," Mrs. Tolman admitted. "You see, if I am to keep pace with my big son and daughter I must look my best; so I have not only brought the extra suitcase but I am going to be tremendously fussy as to where it is put."

"I do believe Mater's brought all her jewels with her!" Steve declared wickedly. "Well, she shall have her sunbursts, tiaras, and things where she can keep her eye on them every moment. Suppose I put them down here at your feet, Mother."

Without further ado, he started to lift the basket suitcase into the car.

"Don't tip it up, son. Don't tip it up!" cautioned his mother.

"Your mother is afraid of knocking some of the pearls or emeralds out of their setting," chuckled Mr. Tolman. "Go easy, Steve!"

A general laugh arose as the offending piece of baggage was stowed away out of sight. An instant later wraps and rugs were bundled in, everybody was cosily tucked up, and Mr. Tolman placed his hands on the wheel.

"Now we're off, Dad!" cried Stephen, as he sprang in beside his father. Mr. Tolman needed no second bidding.

There was a whir, a leap forward, and the automobile glided down the long avenue and out into the highway.

Steve, studying the road map, was too much interested in tracing out the route they were to follow to notice that after the car had spun along smoothly for several miles its speed lessened, and it was not until it came to a complete standstill that he aroused himself from his preoccupation sufficiently to see that his father was bending forward over the starter.

"What's wrong, Henry?" inquired his wife from the back seat.

"I can't imagine," was the impatient reply. "Had I not left the tank with gasoline in it, I should say it was empty; but of course that cannot be the case, for I always keep enough in it to carry us to the garage. Otherwise we should be stalled at our own doorstep and not able to get anywhere."

Climbing out, he began to unscrew the metal top of the tank while Stephen watched him in consternation.

The boy did not need to hear the result of the investigation for already the wretched truth flashed upon him. The tank was empty; of course it was! He knew that without being told. Had not the workman who had replenished it Wednesday said quite plainly that there was only enough gas in it to get him home to Coventry? He should have remembered to stop at the garage and take on an extra supply on the way back as his father always did. How stupid he had been! In his haste to get home he had forgotten every other consideration and the present dilemma was the result of his thoughtlessness. Yet how could he have stopped at the Coventry garage even had he thought of it? All the men there knew him and his father, and if he had gone there or had even driven through the center of the town somebody would have been sure to see him and mention the incident. Why, it was to avoid this very danger that he had returned by the less frequented way.

The man in the brown jeans had certainly calculated to a nicety when he measured out that gasoline. He had not meant him to do any more riding that day; that was apparent. What business was it of his, anyway, and why was he so solicitous as to where he went? There was something puzzling about that man. Steve had thought so at the time. Not that it mattered now. All that did matter was that here they were stalled at the side of the road in almost the same spot where he had been stalled the other day; and they were there because he had neglected to procure gasoline.

The lad felt the hot blood throb in his cheeks. Again the chance for confession confronted him and again his tongue was tied. In a word he could have explained the whole predicament; but he did not. Instead he sat as if stunned, the heart inside him pounding violently. He saw that his father was not only deeply annoyed but baffled to solve the incident.

"The gas is all out; that's the trouble!" he announced.

"What are we going to do, Dad?" inquired Doris anxiously.

"Oh, we can get more all right, daughter," returned her father reassuringly. "Don't worry, my dear. But what I can't understand is how we come to be in such a plight."

"Doesn't gasoline evaporate, Henry?" suggested Mrs. Tolman.

"To some extent, yes; but there could be no such shrinkage as this unless there was a leak in the tank. I never dreamed the supply was so low. Well, it is my own fault. I should have made sure everything was right before we started."

Steve shifted his position uncomfortably. He was manly enough not to enjoy hearing his father shoulder blame that did not rightfully belong to him.

"Now let me think what we had better do," went on Mr. Tolman. "Unfortunately there isn't a house in sight from which we can telephone for help; and we are fully five miles from Torrington. Our only hope is that some one bound for the town may overtake us and allow Steve to ride to the village for aid."

"Couldn't I walk it, Dad?" asked the boy, with an impulse to make good the mischief he had done.

"Oh, no; I wouldn't do that unless the worst befalls," his father replied kindly. "We should gain nothing. It is a long tramp and would simply be a waste of time. Let us wait like Mr. Micawber, and see if something does not turn up."

Wretchedly Stephen settled back into his seat. He would rather have walked to Torrington, done almost anything rather than remain there in the quiet autumn stillness and listen to the accusations of his conscience. What a coward he was!

"It is a shame for us to be tied up here!" he heard Doris complain.

"I know it, daughter, and I am as sorry as you are," responded her father patiently. "In fact, probably, I am more sorry, since it is through my own carelessness that we are stranded."

Again the impulse to blurt out the truth and take the blame that belonged to him took possession of Stephen; but with resolution he forced it back. Nervously he fingered the road map. If he had only spoken at the beginning! It was harder now. He should have made a clean breast of the whole affair when his father got home from New York. Then was the time to have done it. But since he had let that opportunity pass it was awkward, almost absurd, to make confession now. He would much better keep still.

In the meanwhile a gradual depression fell upon the occupants of the car. Mrs. Tolman did not speak; Doris subsided into hushed annoyance; and Mr. Tolman began to pace back and forth at the side of the road and anxiously scan the stretch of macadam that narrowed away between the avenue of trees bordering the highway. Presently he uttered an exclamation of relief.

"Here comes a truck!" he cried. "We will tip the driver and persuade him to let you ride on to Torrington with him, Steve. This is great luck!"

Stepping into the pathway of the approaching car he held up his hand and the passer-by came to a stop beside him.

Stephen looked up expectantly; then a thrill of foreboding seized him and he quickly turned his head aside. It needed no second glance to assure him that the man whom his father was addressing was none other than the workman in the brown jeans who had rescued him from his former plight. He bent lower over the road map, trying to conceal his face and decide what to do. In another moment the teamster would probably recognize him, recall the incident of their former meeting, and hailing him as an old acquaintance, relate the entire story. The possibility was appalling, but terrible as it was it did not equal the disquietude he experienced when he heard his father ejaculate with sudden surprise:

"Why, if it isn't O'Malley! I did not recognize you, Jake. You are just in time to extricate us from a most inconvenient situation. We are headed for Northampton and find ourselves without gasoline. If you can take my son along to Torrington with you so he can hunt up a garage and ride back with some one on a service car I shall be very grateful to you."

"I'd be glad to go myself, sir."

"No, no! I shall not allow you to do that," protested Mr. Tolman. "You are on your way to work and I could not think of detaining you. All I ask is that you take my boy along to the village."

"I'd really be pleased to go, sir," reiterated O'Malley. "I am in no great rush."

"No, I shan't hear to it, Jake," Mr. Tolman repeated. "Nevertheless I appreciate your offer. Take the boy along and that is all I'll ask. Come, Steve, jump aboard! O'Malley, son, is one of our railroad people, whose services we value highly. He is going to be good enough to let you ride over to Torrington with him."

Although the introduction compelled Stephen to give the waiting employee a nod of greeting, he did not meet his eye or evince any sign of recognition, and he sensed that the light that had flashed into the man's face at sight of him died out as quickly as it had come. The boy had an uncomfortable realization as he climbed to the seat of the truck and took his place beside its driver that O'Malley must be rating him as a snob. No one but a cad would accept a stranger's kindness and then cut him dead the next time he encountered him. It was better to endure this misjudgment, however, than to acknowledge a previous acquaintance with the mechanic and thereby arouse his father's suspicion and curiosity. Hence, without further parley, he settled himself and in silence the truck started off.

For some minutes he waited, expecting that when they were well out of earshot of the family the man at the wheel would turn and with a laugh make some reference to the adventure of the past week. It certainly must have amused him to find the great red car again stalled in the same spot, and what would be more natural than that he should comment on the coincidence and perhaps make a joke of the circumstance? But to the boy's chagrin the teamster did no such thing. Instead he kept his eyes fixed on the road and gave no evidence that he had ever before seen the lad at his elbow.

Stephen was aghast. It was not possible the workman had forgotten the happening. He began to feel very uncomfortable. As the landscape slipped past and the car sped on, the distance to Torrington lessened. Still there seemed to be no prospect of the stranger at the wheel breaking his silence. If it had merely been a silence perhaps Steve would not have minded so much; but there was an implied rebuke in the stillness that nettled and stung and left him with a consciousness of being ignored by a superior being.

"I say!" he burst out, when he could endure the ignominy of his position no longer, "don't you remember me, Mr. O'Malley?"

The man who guided the car did not turn his head but he nodded.

"I remember you all right," replied he politely. "I just thought you did not remember me."

"Oh, I remembered you right away," declared Steve eagerly.

"Did you?"

There was a subtle irony in the tone that the lad was not clever enough to detect.

"Of course."

"Is that so!" came dryly from O'Malley.

"Yes, indeed! I remembered you right away," Steve stumbled on. "You are the man who gave me the gasoline when I was stuck here Wednesday."

"I am."

"I knew you the first minute I saw you," repeated Stephen.

"I did not notice any sign that you did," was the terse response.

"Oh—well—you see, I couldn't very well speak back there," explained Steve with confusion. "They would all have wanted to know where I—I mean I would have to—it would just have made a lot of talk," concluded he lamely.

For the first time the elder man, moving his eyes from the ribbon of gleaming highway, confronted him.

"So your father did not know you had the car out the other day?" said he.

"N—o."

The workman showed no surprise.

"I guessed as much," he remarked. "But of course you have told him since."

"Not yet," Steve stammered. "I was going to—honest I was; but things kept interrupting until it got to be so late that it seemed silly to rake the matter all up. Besides, I shan't do it again, so what is the use of jawing about it?"

He stopped, awaiting a response from the railroad employee; but none came.

"Anyhow," he argued with rising irritability, "what good does it do to discuss things that are over and done with? You can't undo them."

The man at the wheel vouchsafed no answer.

"It is because I forgot to stop for more gas when I went home the other day that we are in this fix now," Steve finally blurted out, finding relief in brutal confession.

Still the only reply to his monologue was the chugging of the engine.

At last his voice rose to a higher pitch and there was anger in it.

"I'm talking to you," he shouted in exasperation.

"I am listening."

"Well, why don't you say something?"

"What is there to say?"

"Why—eh—you could tell me what you think."

"I guess you know that already."

Stephen's face turned scarlet.

"I did intend to tell my father," repeated he, instantly on the defensive. "Straight goods, I did."

The man shrugged his shoulders.

"It was only that it didn't seem to come right. You know how things go sometimes."

He saw the workman's lip curl.

"You think I ought to have told."

"Have I said so?"

"No, but I know you do think so."

"I wasn't aware I'd expressed any opinion."

"No—but—well—hang it all—you think I am a coward for not making a clean breast of the whole thing!" cried Stephen, now thoroughly enraged.

"What do you think yourself?" O'Malley suddenly inquired with disconcerting directness.

"Oh, I know I've been rotten," admitted the boy. "Still, even now—" He paused.

"You mean that even now it isn't too late?" put in the truckman, his face lighting to a smile.

"N—o; that wasn't exactly what I was going to say," began the lad, resuming his argumentative tone. "What I mean is that—"

A swift frown replaced the elder man's smile.

"Here we are at the garage," he broke in. "They will do whatever you want them to."

He seemed in a hurry and as Stephen could find no excuse for lingering he climbed reluctantly out of the truck and stood balancing himself on the curb that edged the sidewalk.

"I'm much obliged to you for bringing me over," he observed awkwardly.

"That's all right."

The man in the brown jeans started his engine.

"Say, Mr. O'Malley!" called Stephen desperately.

"Well?"

"You—you—won't tell my father about my taking the car, will you?" he pleaded wretchedly.

"I tell him?"

Never had he heard so much scorn compressed into three words.

"You need have no worries," declared the man over his shoulder, a contemptuous sneer curling his lips. "I confess my own wrong-doing but I do not tattle the sins of other people. Your father will never be the wiser about you so far as I am concerned. Whatever you want him to know you will have to tell him yourself."

Baffled, mortified, and stinging with humiliation as if he had been whipped, Stephen watched him disappear round the bend of the road.

O'Malley despised him, that he knew; and he did not at all relish being despised.

While hunting up the garage and negotiating for gasoline Steve thrust resolutely from his mind his encounter with O'Malley and the galling sense of inferiority it carried with it; but once on the highroad again the smart returned and the sting lingering behind the man's scorn was not to be allayed. It required every excuse his wounded dignity could muster to bolster up his pride and make out for himself the plausible case that had previously comforted him and lulled his conscience to rest. It was now more impossible than ever for him to make any confession, he decided; for having denied in his father's presence O'Malley's acquaintance it would be ridiculous to acknowledge that he had known the truck driver all along. Of course he could not do that. Whatever he might have said or done at the time, it was entirely too late to go back on his conduct now. One event had followed on the heels of another until to slip out a single stone of the structure he had built up would topple over the whole house.

If he had spoken in the beginning that would have been quite simple. All he could do now was to let bygones be bygones and in the pleasure of to-day forget the mistakes of yesterday. Consoled by this reflection he managed to recapture such a degree of his self-esteem that by the time he rejoined the family he was once more holding his head in the air and smiling with his wonted lightness of heart.

"We shall get you to Northampton now, daughter, without more delay, I hope," Mrs. Tolman affirmed when the car was again skimming along. "We may be a bit behind schedule; nevertheless a late arrival by motor will be pleasanter than to have made the trip by train."

"I should say so!" was the fervent ejaculation.

"Come, come!" interrupted Mr. Tolman. "I shall not sit back and allow you two people to cry down the railroads. They are not perfect, I will admit, and unquestionably trains do not always go at the hours we wish they did; a touring car is, perhaps, a more comfortable and luxurious method of travel, especially in summer. But just as it is an improvement over the train, so the train was a mighty advance over the stagecoach of olden days."

"Oh, I don't know, Dad," Stephen mused. "I am not so sure that I should not have liked stagecoaches better. Think what jolly sport it must have been to drive all over the country!"

"In fine weather, yes—that is, if the roads had been as excellent as they are now; but you must remember that in the old coaching days road-building had not reached its present perfection. Traveling by stage over a rough highway in a conveyance that had few springs was not so comfortable an undertaking as it is sometimes pictured. Furthermore you must not forget that it was also perilous, for not only was there danger from accident on these poorly constructed, unlighted thoroughfares but there was in addition the menace from highwaymen in the less populated districts. It took a great while to make a journey of any length, too, and to sleep in a coach where one was cramped, jolted, and either none too warm or miserably hot was not an unalloyed delight, as I am sure you will agree."

"I had not thought of any of those things," owned Stephen. "It just seemed on the face of it as if it must have been fun to ride on top of the coach and see the sights as one does from the Fifth Avenue or London buses."

"Oh," laughed his father, "a few hours' adventure like that is quite a different affair from making a stagecoach journey. I grant that to ride on a clear morning through the streets of a great city, or bowl along the velvet roads of a picturesque countryside as one frequently does in England is very delightful. To read Dickens' descriptions of journeys up to London is to long to don a greatcoat, wind a muffler about one's neck, and amid the cracking of whips and tooting of horns dash off behind the horses for the fairy city his pen portrays. Who would not have liked, for example, to set out with Mr. Pickwick for the Christmas holidays at Dingley Dell? Why, you cannot even read about it without seeing in your mind's eye the envious throng that crowded the inn yard and watched while the stableboys loosed the heads of the leaders and the steeds galloped away! And those marvelous country taverns he depicts, with their roaring fires, their steaming roasts, their big platters of fowl deluged in gravy, and their hot puddings! Was there ever writer more tantalizing?"

"You will have us all hungry in two minutes, Dad, if you keep on," exclaimed Stephen.

"And Dickens has us hungry, too," declared Mr. Tolman. "Nevertheless we must not forget that he paints but one side of the picture. He fails to emphasize what such a trip meant when the weather was cold and stormy, and those outside the coach as well as those inside it were often drenched with rain or snow, and well-nigh frozen to death. Moreover, while it is true that many of the inns along the turnpike were clean and furnished excellent fare, there were others that could boast nothing better than chilly rooms, damp beds, and only a very limited hospitality."

"I believe you are a realist, Henry," said his wife playfully.

Her husband laughed.

"Nor must we lose sight of the time consumed by making a trip by coach," he went on. "Business in those days was not such a rushing matter as it is now, of course; yet even when issues of importance were at stake, or crises of life and death were to be met, there was no hurrying things beyond a certain point. Physical impossibility prohibited it. Horses driven at their liveliest pace could cover only a comparatively small number of miles an hour; and at the points where the relays were changed, or the horses fed and rested; the mails deposited or taken aboard; and passengers left or picked up, there were unavoidable delays. In fact, the strongest argument against the stagecoach, and the one that influenced public opinion the most, was this so-called fast-mail service; for in order to make connections with other mail coaches along the route and not forfeit the money paid for doing so, horses were often driven at such a merciless rate of speed that the poor creatures became total wrecks within a very short time. Many a horse fell in its tracks in the inn yards, having been lashed along to make the necessary ten miles an hour and reach a specified town on schedule. Other horses were maimed for life. It is tragic to consider that in England before the advent of the railroad about thirty thousand horses were annually either killed outright or injured so badly that they were of little use afterward."

"Great Scott, Dad!" ejaculated Stephen.

"And England was no more guilty in this respect than was America, for in the early days of our own country when people were demanding quicker transportation and swifter mail service thousands of noble beasts offered up their last breath in making the required rate of speed."

"I suppose nobody thought about the horses," murmured the boy. "I am sure I didn't."

"If the public thought at all it was too selfish to care, I am afraid, until threatened by the possibility of the total extermination of these creatures," was his father's reply. "This danger, blended with a humane impulse which rose from the gentler-minded portion of the populace, was the decisive factor in urging men to seek out some other method of travel. Then, too, the world was waking up commercially and it was becoming imperative to find better ways for transporting the ever increasing supplies of merchandise. The quick moving of troops from one point to another was also an issue. Although the canals of England enabled the government to carry quite a large body of men, the method was a slow one. In 1806, for instance, it took exactly a week to shift troops from Liverpool to London, a distance of thirty-four miles."

"Why, they could have marched it in less time than that, couldn't they?" questioned Doris derisively.

"Yes, the journey might easily have been made on foot in two days," nodded her father. "But in war time a long march which exhausts the soldiers is frequently an unwise policy, for the men are in no condition when they arrive to go into immediate action, as reënforcements often must."

"I see," answered Doris.

"When the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad was opened in 1830 this thirty-four miles was covered in two hours," continued Mr. Tolman. "Of course the quick transportation of troops was then, as now, of very vital importance. We have had plenty of illustrations of that in our recent war against Germany. Frequently the fate of a battle has hung on large reënforcements being speedily dispatched to a weak point in the line. Moreover, by means of the railroads, vast quantities of food, ammunition and supplies of all sorts can constantly be sent forward to the men in action. During the late war our American engineers laid miles and miles of track under fire, thereby keeping open the route to the front so that there was no danger of the fighters being cut off and left unequipped. It was a service for which they, as well as our nation, won the highest praise. And not only was there a constant flow of supplies but it was by means of these railroads that hospital trains were enabled to carry to dressing stations far behind the lines thousands of wounded men whose lives might otherwise have been lost."

"I suppose the slightly wounded could be made more comfortable in this way, too," Mrs. Tolman suggested.

"Yes, indeed," was the reply. "Not only were the men better cared for in the roomier hospitals behind the lines, but as there was more space there the peril from contagion, always a menace when large numbers of sick are packed closely together, was greatly lessened; for there is nothing army doctors dread so much as an epidemic of disease when there is not enough room to isolate the patients."

"When did England adopt railroads in place of stagecoaches, Dad?" asked Doris presently.

At the question her father laughed.

"See here!" he protested good-humoredly, "what do you think I am? Just because I happen to be a superintendent do you think me a volume of railroad history, young woman? The topic, I confess, is a fascinating one; but I am off for a vacation to-day."

"Oh, tell us, Dad, do!" urged the girl.

"Nonsense! What is the use of spoiling a fine morning like this talking business?" objected her father.

"But it is not business to us," interrupted Mrs. Tolman. "It is simple a story—a sort of fairy tale."

"It is not unlike a fairy tale, that's a fact," reflected her husband gravely. "Imagine yourself back, then, in 1700, before steam power was in use in England. Now you must not suppose that steam had never been heard of, for an ancient Alexandrian record dated 120 B. C. describes a steam turbine, steam fountain, and steam boiler; nevertheless, Hero, the historian who tells us of them, leaves us in doubt as to whether these wonders were actually worked out, or if they were, whether they were anything but miniature models. Still the fact that they are mentioned goes to prove that there were persons in the world who at a very early date vaguely realized the possibilities of steam as a force, whether turned to practical uses or not. For years the subject remained an alluring one which led many a scientist into experiments without number. In various parts of the world men played with the idea and wrote about it; but no one actually produced any practical steam contrivance until 1650, when the second Marquis of Worcester constructed a steam fountain that could force the water from the moat around his castle as high as the top of one of the towers. The feat was looked upon as a marvel and afterward a larger fountain, similar in principle, was constructed at Vauxhall and from that time on the future of steam as a motive power was assured."

"Did the Marquis of Worcester go on with his experiments and make other things?" demanded Stephen.

"Apparently not," replied his father. "He did, nevertheless, furnish a basis for others to work on. Scientists were encouraged to investigate with redoubled zeal this strange vapor which, when controlled and directed, could carry water to the top of a castle tower. When in 1698 Savery turned Worcester's crude steam fountain to draining mines and carrying a water supply, every vestige of doubt that this mighty power could be applied to practical uses vanished."

"Did the steam engine come soon afterward?" queried Doris, who had become interested in the story.

"No, not immediately," answered Mr. Tolman, pausing to shift the gear of the car. "Before the steam engine, as we know it, saw the light, there had to be more experimenting and improving of the steam fountain. It was not until 1705 that Thomas Newcomen and his partner, John Calley, invented and patented the first real steam engine. Of course it was not in the least like the engines we use now. Still, it was a steam device with moving parts which would pump water, a tremendous advance over the mechanisms of the past where all the power had been secured by the alternate filling and emptying of a vacuum, or vacant receptacle, attached to the pump. Now, with Newcomen's engine a complete revolution took place. The engine with moving parts, the ancestor of our modern exquisitely constructed machinery, speedily crowded out the primitive steam fountain idea. The new device was very imperfect, there can be no question about that; but just as the steam fountain furnished the inspiration for the engine with moving parts, so this forward step became the working hypothesis for the engines that followed."

"What engines did follow?" Doris persisted, "and who did invent our steam engine?"

"Silly! And you in college," jeered Steve disdainfully.

"I am not taking a course in steam engines there," laughed his sister teasingly. "Anyway, girls are not expected to know who invented all the machines in the world, are they, Dad?"

Mr. Tolman waited a moment, then said soothingly:

"No, dear. Girls are not usually so much interested in scientific subjects as boys are—although why they should not be I never could quite understand. Nevertheless, I think it might be as well for even a girl to know to whom we are indebted for such a significant invention as the steam engine.

"It was James Watt," Stephen asserted triumphantly.

"It certainly was," his father agreed. "And since your brother has his information at his tongue's end, suppose we get him to tell us more about this remarkable person."

Stephen flushed.

"I'm afraid," began he lamely, "that I don't know much more. You see, I studied about him quite a long time ago and I don't remember the details. I should have to look it up. I do recall the name, though—"

His father looked amused.

"I don't know which of you children is the more blameworthy," remarked he in a bantering tone. "Doris, who never heard of Watt; or Stephen, who has forgotten all about him."

Both the boy and the girl chuckled good-humoredly.

"At least I knew his name, Dad—give me credit for that," piped Steve.

"That was something, certainly," Mrs. Tolman declared, joining in the laugh.

"Well, since neither of us can furnish the story, I don't see but that you will have to do it, Dad," Doris said mischievously.

"It would be a terrible humiliation if I should discover that I could not do it, wouldn't it?" replied Mr. Tolman with a smile. "In point of fact, there actually is not a great deal more that it is essential for one to know. It was by perfecting the engines of the Newcomen type and adding to them first one and then another valuable device that Watt finally built up the forerunner of our present-day engine. The progression was a gradual one. Now he would better one part, then some other. He surrounded the cylinder, for example, with a jacket, or chamber, which contained steam at the same pressure as that within the boiler, thereby keeping it as hot as the steam that entered it—a very important improvement over the old idea; then he worked out a plan by which the steam could be admitted at each end of the cylinder instead of at one end, as was the case with former engines. The latter innovation resulted in the push and pull of the piston rod. So it went."

"How did Watt come to know so much about engines?" asked Stephen.

"Oh, Watt was an engineer by trade—or rather he was a maker of mathematical instruments for the University of Glasgow, where he came into touch with a Newcomen engine. He also made surveys of rivers, harbors, and canals. So you see it was quite a consistent thing that a man with such a bent of mind should take up the pastime of experimenting with a toy like the steam engine in his leisure hours."

"Did he go so far as to patent it, Henry?" Mrs. Tolman questioned.

"Yes, he did. Many of our scientists either had not the wit to do this, alas, or else they were too impractical to appreciate the value of their ideas. In consequence the glory and financial benefit of what they did was often filched from them. But Watt was a Scotchman and canny enough to realize to some extent what his invention was worth. He therefore obtained a patent on it which was good for twenty-five years; and when, in 1800, this right expired he retired from business with both fame and fortune."

"It is nice to hear of one inventor who got something out of his toil," Mrs. Tolman observed.

"Indeed it is. Think of the many men who have slaved day and night, forfeited health, friends, and money to give to the world an idea, and never lived to receive either gratitude or financial reward, dying unknown or entirely forgotten. There is something tragic about the injustice of it. But Watt, I am glad to say, lived long enough to witness the service he had done mankind and enjoy an honored place among the great of the world."

"Is the kind of engine Watt invented now in use?" Doris inquired.

"Yes, that is a double-acting or reciprocating engine of a more perfect type," her father returned. "Mechanics and engineers went on improving Watt's engine just as he had improved those that had preceded it. It is interesting, too, to notice that after thousands of years scientists have again worked around to the steam turbine described so long ago in the Alexandrian records. This engine, although it does away with many of the moving parts introduced by Newcomen, preserves the essential principles of that early engine combined with Watt's later improvements. To-day we have a number of different kinds of engines, their variety differing with the purpose to which they are applied. Their cost, weight, and the space they require have been reduced and their power increased, and in addition we have made it possible to run them not only by means of coal or wood but by gasoline, oil, or electricity. We have small, light-weight engines for navigation use; mighty engines to propel our great warships and ocean liners; stationary engines for mills and power plants; to say nothing of the wonderful locomotive engines that can draw the heaviest trains over the highest of mountains. The principle of all these engines is, however, the same and for the brain behind them we must thank James Watt."

"Was it Watt who invented the locomotive, too?" ventured Doris. Her father shook his head.

"The perfecting of the locomotive, my dear, is, as Kipling says, another story."

"Tell it to us."

"Not now, daughter," protested Mr. Tolman. "I am far too hungry; and more than that I am eager to enjoy this beautiful country and forget railroads and locomotives."

"Did you say you were hungry, Henry?" asked Mrs. Tolman.

"I am—starved!" her husband said apologetically. "Isn't it absurd to be hungry so early in the day?"

"It is nearly noon, Dad!" said Steve, glancing down at the clock in the front of the car.

"Noon! Why, I thought it was still the middle of the morning."

"No, indeed! While you have been talking we have come many a mile, and the time has slipped past," his wife said. "If all goes well—" The shot from a bursting tire rent the air.

"Which evidently it does not," interrupted Mr. Tolman grimly, bringing the car to a stop. "How aggravating! We were almost into Palmer, where I had planned for us to lunch. Now it may be some little time before we can get anything to eat."

"Motorist's luck! Motorist's luck, my dear!" cried Mrs. Tolman gaily. "An automobilist must resign himself to taking cheerfully what comes."

"That is all very well," grumbled her husband, as he clambered out of the car. "Nevertheless you must admit that this mishap on the heels of the other one is annoying."

Stephen also got out and the two bent to examine the punctured tire.

"I should not mind so much if I were not so hungry," murmured Mr. Tolman. "How are you, Steve? Fainting away?"

The boy laughed.

"Well, I could eat something if I had it," he confessed.

"I wish I hadn't mentioned food," went on Mr. Tolman humorously. "It was an unfortunate suggestion."

"I'm hungry, too," piped Doris.

"There, you see the epidemic you have started, Henry," called Mrs. Tolman accusingly. "Here is Doris vowing she is in the last throes of starvation."

Nobody noticed that in the meanwhile the mother had reached down and lifted into her lap the small suitcase hidden in the bottom of the car. She opened the cover and began to remove its contents.

At length, when a remark her husband made to her went unheeded, he sensed her preoccupation and came around to the side of the car where she was sitting. Immediately he gave a cry of surprise.

"My word!" he exclaimed. "Steve, come here and see what your mother has."

There sat Mrs. Tolman, unpacking with quiet enjoyment sandwiches, eggs, cake, cookies, and olives.

A shout of pleasure rose from the famished travelers.

"So it was not your jewels, after all, Mater!" cried Stephen.

"No, and after the way you have slandered me and my little suitcase, none of you deserve a thing to eat," his mother replied. "However, I am going to be magnanimous if only to shame you. Now climb in and we will have our lunch. You can fix the tire afterward."

The men were only too willing to obey.

As with brightened faces they took their seats in the car, Stephen smiled with affection at his mother.

"Well, Mater, Watt was not the only person who lived to see himself appreciated; and I don't believe people were any more grateful to him for his steam engine than we are to you right now for this luncheon. You are the best mother I ever had."

The new tire went on with unexpected ease and early afternoon saw the Tolmans once more bowling along the highway toward Northampton. The valley of the Connecticut was decked with harvest products as for an autumnal pageant. Stacks of corn dotted the fields and pyramids of golden pumpkins and scarlet apples made happy the verandas of the old homesteads or brightened the doorways of the great red barns flanking them.

"All that is needed to transform the scene into a giant Hallowe'en festival is to have a witch whisk by on a broomstick, or a ghost bob up from behind a tombstone," declared Mrs. Tolman. "Just think! If we had come by train we would have missed all this beauty."

"I see plainly that you do not appreciate the railroads, my dear," returned her husband mischievously. "This is the second time to-day that you have slandered them. You sound like the early American traveler who asserted that it was ridiculous to build railroads which did very uncomfortably in two days what could be done delightfully by coach in eight or ten."

"Why, I should have thought people who had never heard of motor-cars would have welcomed the quicker transportation the railroads offered," was Mrs. Tolman's reply.

"One would have thought so," answered Mr. Tolman. "Still, when we recall how primitive the first railroads were, the prejudice against them is not to be wondered at."

"How did they differ from those we have now, Dad?" Doris asked.

"In almost every way," answered her father, with a smile. "You see at the time Stephenson invented his steam locomotive nothing was known of this novel method of travel. As I told you, persons were accustomed to make journeys either by coach or canal. Then the steam engine was invented and immediately the notion that this power might be applied to transportation took possession of the minds of people in different parts of England. As a result, first one and then another made a crude locomotive and tried it out without scruple on the public highway, where it not only frightened horses but terrified the passers-by. Many an amusing story is told of the adventures of these amateur locomotives. A machinist named Murdock, who was one of James Watt's assistants, built a sort of grasshopper engine with very long piston rods and with legs at the back to help push it along; with this odd contrivance he ventured out into the road one night just at twilight. Unfortunately, however, his restless toy started off before he was ready to have it, and turning down an unfrequented lane encountered a timid clergyman who was taking a peaceful stroll and frightened the old gentleman almost out of his wits. The poor man had never seen a locomotive before and when the steaming object with its glowing furnace and its host of moving arms and legs came puffing toward him through the dusk he was overwhelmed with terror and screamed loudly for help."

A laugh arose from the listeners.

"And that is but one of the many droll experiences of the first locomotive makers," continued Mr. Tolman. "For example Trevithick, another pioneer in the field, also built a small steam locomotive which he took out on the road for a trial trip. It chanced that during the experimental journey he and his fireman came to a tollgate and puffing up to the keeper with the baby steam engine, they asked what the fee would be for it to pass. Now the gate keeper, like the minister, had had no acquaintance with locomotives, and on seeing the panting red object looming like a specter out of the darkness and hearing a man's voice intermingled with its gasps and snorts, he shouted with chattering teeth:

"There is nothing to pay, my dear Mr. Devil! Just d-r-i-v-e along as f-a-s-t—as—ever—you—can."

His hearers applauded the story.

"Who did finally invent the railroad?" inquired Doris after the merriment had subsided.

"George Stephenson, an Englishman," replied her father. "For some time he had been experimenting with steam locomotives at the Newcastle coal mines where some agency stronger than mules or horses was needed to carry the products from one place to another. He had no idea of transporting people when he began to work out the suggestion. All he thought of was a coal train which would run on short lengths of track from mine to mine. But the notion assumed unexpected proportions until the Darlington road, the most ambitious of his projects, reached the astonishing distance of thirty-seven miles. When the rails for it were laid the engineer intended it should be used merely for coal transportation, as its predecessors had been; but some of the miners who lived along the route and were daily obliged to go back and forth to work begged that some sort of a conveyance be made that could also run along the track and enable them to ride to work instead of walking. So a little log house not unlike a log cabin, with a table in the middle and some chairs around it, was mounted on a cart that fitted the rails, and a horse was harnessed to the unique vehicle."

"And it was this log cabin on wheels that gave Stephenson his inspiration for a railroad train!" gasped Doris.

"Yes," nodded her father. "When the engineer saw the crude object the first question that came to him was why could not a steam locomotive propel cars filled with people as well as cars filled with coal. Accordingly he set to work and had several coach bodies mounted on trucks, installing a lever brake at the front of each one beside the coachman's box. In front of the grotesque procession he placed a steam locomotive and when he had fastened the coaches together he had the first passenger train ever seen."

"It must have been a funny looking thing!" Steve exclaimed, smiling with amusement at the picture the words suggested.

"It certainly was," agreed his father. "If you really wish to know how funny, some time look up the prints of this great-great-grandfather of our present-day Pullman and you will be well repaid for your trouble; the contrast is laughable."

"But was this absurd venture a success?" queried Mrs. Tolman incredulously.

"Indeed it was!" returned her husband. "In fact, Stephenson, like Watt, was one of the few world benefactors whose gift to humanity was instantly hailed with appreciation. The railroad was, to be sure, a wretched little affair when viewed from our modern standpoint, for there were no gates at the crossings, no signals, springless cars, and every imaginable discomfort. Fortunately, however, our ancestors had not grown up amid the luxuries of this era, and being of rugged stock that was well accustomed to hardships of every variety they pronounced the invention a marvel, which in truth it was.

"You've said it!" chuckled Steve in the slang of the day.

"In the meantime," went on Mr. Tolman, "conditions all over England were becoming more and more congested, and from every direction a clamor arose for a remedy. You see the invention of steam spinning machinery had greatly increased the output of the Manchester cotton mills until there was no such thing as getting such a vast bulk of merchandise to those who were eager to have it. Bales of goods waiting to be transported to Liverpool not only overflowed the warehouses but were even stacked in the open streets where they were at the mercy of robbers and storms. The canals had all the business they could handle, and as is always the result in such cases their owners became arrogant under their prosperity and raised their prices, making not the slightest attempt to help the public out of its dilemma. Undoubtedly something had to be done and in desperation a committee from Parliament sent for Stephenson that they might discuss with him the feasibility of building a railroad from Manchester to Liverpool. The committee had no great faith in the enterprise. Most of its members did not believe that a railroad of any sort was practical or that it could ever attain speed enough to be of service. However, it was a possibility, and as they did not know which way to turn to quiet the exasperated populace they felt they might as well investigate this remedy. It could do no harm."

Mr. Tolman paused as he stooped to change the gear of the car.

"So Stephenson came before the board, and one question after another was hurled at him. When, however, he was asked, half in ridicule, whether or not his locomotive could make thirty miles an hour and he answered in the affirmative, a shout of derision arose from the Parliament members. Nobody believed such a miracle possible. Nevertheless, in spite of their sceptical attitude, it was finally decided to build the Liverpool-Manchester road and about a year before its opening a date was set for a contest of locomotives to compete for the five-hundred-pound prize offered by the directors of the road."

"I suppose ever so many engines entered the lists," ventured Steve with interest.

"There were four," returned his father.

"And Stephenson drove one of them?"

"Yes."

"Oh, I hope it got the prize!" put in Doris eagerly.

Her father smiled at her earnestness.

"It did," was his reply. "Stephenson's engine was called the 'Rocket' and was a great improvement over the locomotive he had used at the mines, for this one had not only a steam blast but a multi-tubular boiler, a tremendous advance in engine building."

"I suppose that the winner of the prize not only got the money the road offered but his engine was the one chosen as a pattern for those to be used on the new railroad," ventured Stephen.

"Precisely. So you see a great deal depended on the showing each locomotive made. Unluckily in the excitement a tinder box had been forgotten, and when it came time to start, the spark to light the fires had to be obtained from a reading glass borrowed from one of the spectators. This, of course, caused some delay. But once the fires were blazing and steam up, the engines puffed away to the delight of those looking on."

"I am glad Stephenson was the winner," put in Doris.

"Yes," agreed her father. "He had worked hard and deserved success. It would not have seemed fair for some one else to have stolen the fruit of his toil and brain. Yet notwithstanding this, his path to fame was not entirely smooth. Few persons win out without surmounting obstacles and Stephenson certainly had his share. Not only was he forced to fight continual opposition, but the opening of the Manchester and Liverpool road, which one might naturally have supposed would be a day of great triumph, was, in spite of its success, attended by a series of catastrophes. It was on September 15, 1830, that the ceremonies took place, and long before the hour set for the gaily decorated trains to pass the route was lined with excited spectators. The cities of Liverpool and Manchester also were thronged with those eager to see the engines start or reach their destination. There were, however, mingled with the crowd many persons who were opposed to the new venture."

"Opposed to it?" Steve repeated with surprise.

"Yes. It seems odd, doesn't it?"

"But why didn't they want a railroad?" persisted the boy. "I thought that was the very thing they were all demanding."

"You must not forget the condition of affairs at the time," said his father. "Remember the advent of steam machinery had deprived many of the cotton spinners of their jobs and in consequence they felt bitterly toward all steam inventions. Then in addition there were the stagecoach drivers who foresaw that if the railroads supplanted coaches they would no longer be needed. Moreover innkeepers were afraid that a termination of stage travel would lessen their trade."

"Each man had his own axe to grind, eh?" smiled Steve.