« back

CONTENTS

- I

- A Terrible Adventure with Hyenas

- By C. Randolph Lichfield

- II

- The Vega Verde Mine

- By Charles Edwardes

- III

- A Very Narrow Shave

- By John Lang

- IV

- An Adventure in Italy

- By J. Kinchin Smith

- V

- The Tapu-tree

- By A. Ferguson

- VI

- Some Panther Stories

- By Various Writers

- VII

- A Midnight Ride on a Californian Ranch

- By A. F. Walker

- VIII

- O'Donnell's Revenge

- By Frank Maclean

- IX

- My Adventure with a Lion

- By Algernon Blackwood

- X

- The Secret Cave of Hydas

- By F. Barford

- Chapter I.—The Fight and Theft in the Museum

- Chapter II.—Mark Mullen Disappears

- Chapter III.—The Mysterious Fakir

- Chapter IV.—A Capture

- Chapter V.—A Valuable Find in the Temple of Atlas

- [Pg iv]

XI

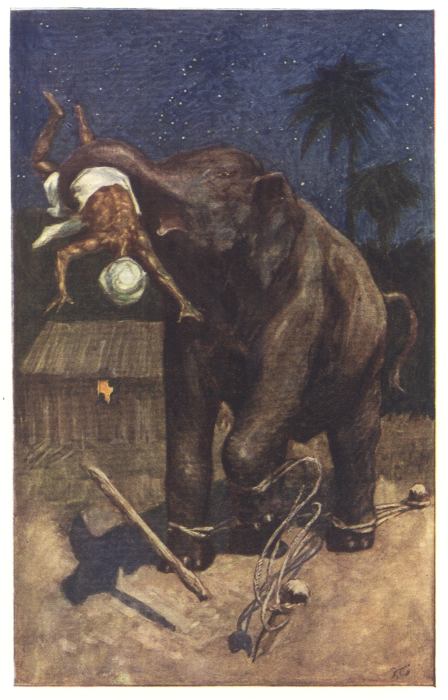

- An Adventure in the Heart of Malay-land

- By Alexander Macdonald, F.R.G.S.

- XII

- A Week-end Adventure

- By William Webster

- XIII

- The Deflected Compass

- By Alfred Colbeck

- XIV

- In Peril in Africa

- By Maurice Kerr

- XV

- Keeping the Tryst

- By E. Cockburn Reynolds

- XVI

- Who Goes There?

- By Rowland W. Cater

- XVII

- A Drowning Messmate

- By A. Lee Knight

- XVIII

- The Pilot of Port Creek

- By Burnett Fallow

ILLUSTRATIONS

ADVENTURES IN MANY LANDS

I

A TERRIBLE ADVENTURE WITH HYENAS

There are many mighty hunters, and most of them can tell of many very thrilling adventures personally undergone with wild beasts; but probably none of them ever went through an experience equalling that which Arthur Spencer, the famous trapper, suffered in the wilds of Africa.

As the right-hand man of Carl Hagenbach, the great Hamburg dealer in wild animals, for whom Spencer trapped some of the finest and rarest beasts ever seen in captivity, thrilling adventures were everyday occurrences to him. The trapper's life is infinitely more exciting and dangerous than the hunter's, inasmuch as the latter hunts to kill, while the trapper hunts to capture, and the relative risks are not, therefore, comparable; but Spencer's adventure with the "scavenger of the wilds," as the spotted hyena is sometimes aptly called, was something so terrible that even he could not recollect it without shuddering.

He was out with his party on an extended trapping expedition, and one day he chanced to get separated from his followers; and, partly overcome by the intense heat and his fatigue, he lay down and fell asleep—about the most dangerous thing a solitary traveller in the interior of Africa can do. Some hours later, when the scorching sun was beginning to settle down in the west, he was aroused by the sound of laughter not far away.

For the moment he thought his followers had found him, and were amused to find him taking his difficulties so comfortably; but hearing the laugh repeated he realised at once that no human being ever gave utterance to quite such a sound; in fact, his trained ear told him it was the cry of the spotted hyena. Now thoroughly awake, he sat up and saw a couple of the ugly brutes about fifty yards away on his left. They were sniffing at the air, and calling. He knew that they had scented him, but had not yet perceived him.

In such a position, as sure a shot and one so well armed as Spencer was, a man who knew less about wild animals and their habits would doubtless have sent the two brutes to earth in double quick time, and thus destroyed himself. But Spencer very well knew from their manner that they were but the advance-guard of a pack. The appearance of the pack, numbering about one hundred, coincided with his thought. To tackle the whole party was, of course, utterly out of the question; to escape by flight was equally out of[Pg 7] the question, for hyenas are remarkably fast travellers.

His only possible chance of escape, therefore, was to hoodwink them, if he could, by feigning to be dead; for it is a characteristic of the hyena to reject flesh that is not putrid. He threw himself down again, and remained motionless, hoping the beasts would think him, though dead, yet unfit for food. It was an off-chance, and he well knew it; but there was nothing else to be done.

In a couple of seconds the advance-guard saw him, and, calling to their fellows, rushed to him. The pack answered the cry and instantly followed. Spencer felt the brutes running over him, felt their foul breath on his neck, as they sniffed at him, snapping, snarling, laughing; but he did not move. One of them took a critical bite at his arm; but he did not stir. They seemed nonplussed. Another tried the condition of his leg, while many of them pulled at his clothes, as if in impotent rage at finding him so fresh. But he did not move; in an agony of suspense he waited motionless.

Presently, to his amazement, he was lifted up by two hyenas, which fixed their teeth in his ankle and his wrist, and, accompanied by the rest, his bearers set off with him swinging between them, sometimes fairly carrying him, sometimes simply dragging him, now and again dropping him for a moment to refix their teeth more firmly in his flesh. Believing him to be dead, they were conveying him to their retreat, there to devour him when he was in a fit condition. He fully realised this, but[Pg 8] he was powerless to defend himself from such a fate.

How far they carried him Spencer could not tell, for from the pain he was suffering from his wounds, and the dreadful strain of being carried in such a manner, he fell into semi-consciousness from time to time; but the distance must have been considerable, for night was over the land and the sky sparkling with stars before the beasts finally halted; and then they dropped him in what he knew, by the horrible and overpowering smell peculiar to hyenas, was the cavern home of the pack. Here he lay throughout the awful night, surrounded by his captors, suffering acutely from his injuries, thirst, and the vile smell of the place.

When morning broke he found that the pack had already gone out in search of more ready food, leaving him in charge of two immense brutes, which watched him narrowly all through the day; for, unarmed as he was, and exhausted, he knew it would be suicide to attempt to tackle his janitors. He could only wait on chance. Once or twice during the day the beasts tried him with their teeth, giving unmistakable signs of disgust at the poor progress he was making. At nightfall they tried him again, and, being apparently hungry, one of them deserted its post and went off, like the others, in search of food.

This gave the wretched man a glimmering of hope, for he knew that the hyena dislikes its own company, and that the remaining beast would certainly desert if the pack remained away long[Pg 9] enough. But for hour after hour the animal stayed on duty, never going farther than the mouth of the cave. When the second morning broke, however, the hyena grew very restless, going out and remaining away for brief periods. But it always returned, and every time it did so Spencer naturally imagined it had seen the pack returning, and that the worst was in store for him. But at length, about noon, the brute went out and did not come back.

Spencer waited and waited, fearing to move lest the creature should only be outside, fearing to tarry lest he should miss his only chance of escaping. After about an hour of this suspense he crept to the mouth of the cave. No living creature was within sight. He got upon his faltering feet, and hurried away as fast as his weakness would permit; but his condition was so deplorable that he had not covered a mile when he collapsed in a faint.

Fortune, however, favours the brave; and although he fell where he might easily have remained for years without being discovered, he was found the same day by a party of Boers, who dressed his wounds, gave him food and drink (which he had not touched for two days), and helped him by easy stages to the coast.

Being a man of iron constitution, he made a rapid and complete recovery, but his wrist, ankle, arms, and thigh still bear the marks of the hideous teeth which, but for his marvellous strength of will, would have torn him, living, to shreds.

II

THE VEGA VERDE MINE

Jim Cayley clambered over the refuse-heaps of the mine, rejoicing in a tremendous appetite which he was soon to have the pleasure of satisfying.

There was also something else.

Little Toro, the kiddy from Cuba—"Somebody's orphan," the Spaniards of the mine called him, with a likely hit at the truth—little Toro had been to the Lago Frio with Jim, to see that he didn't drown of cramp or get eaten by one of the mammoth trout, and had hinted at dark doings to be wrought that very day, at closing time or thereabouts.

Hitherto, Jim had not quite justified his presence at the Vega Verde mine, some four thousand feet above sea-level in these wilds of Asturias. To be sure, he was there for his health. But Mr. Summerfield, the other engineer in partnership with Alfred Cayley, Jim's brother, had, in a thoughtless moment, termed Jim "an idle young dog," and the phrase had stuck. Jim hadn't liked it, and tried to say so. Unfortunately, he stammered, and Don Ferdinando (Mr. Summerfield) had laughed and gone off, saying he couldn't wait.

Now it was Jim's chance. He felt that this was so, and he rejoiced in the sensation as well as in his appetite and the thought of the excellent soup, omelette, cutlets, and other things which it was Mrs. Jumbo's privilege to be serving to the three Englishmen (reckoning Jim in the three) at half-past one o'clock precisely.

Toro had made a great fuss about his news. He was drying Jim at the time, and Jim was saying that he didn't suppose any other English fellow of fifteen had had such a splendid bathe. There were snow-peaks in the distance, slowly melting into that lake, which well deserved its name of "Cold."

"Don Jimmy," said young Toro, pausing with the towel, "what do you think?"

"Think?" said Jimmy. "That I—I—I—I'll punch your black head for you if you don't finish this j—j—j—job, and b—b—b—be quick about it."

He wasn't really fierce with the Cuban kiddy. The Cuban kiddy himself knew that, and grinned as he made for Jim's shoulder.

"Yes, Don Jimmy," he said; "don't you worry about that. But I'm telling you a straight secret this time—no figs about it."

Toro had picked up some peculiar English by association with the Americans who had swamped his native land after the great war. Still, it was quite understandable English.

"A s—s—s—straight secret! Then j—j—just out with it, or I'll p—p—p—punch your head for that as well," said Jimmy, rushing his words.

He often achieved remarkable victories over his affliction by rushing his words. He could do this best with his inferiors, when he hadn't to trouble to think what words he ought to use. At school he made howling mistakes just because of his respectful regard for the masters and that sort of thing. They didn't seem to see how he suffered in his kindly consideration of them.

It was same with Don Ferdinando. Mr. Summerfield was a very great engineering swell when he was at home in London. Jimmy couldn't help feeling rather awed by him. And so his stammering to Don Ferdinando was something "so utterly utter" (as his brother said) that no fellow could listen to it without manifest pain, mirth, or impatience. In Don Ferdinando's case, it was generally impatience. His time was worth pounds a minute or so.

"All right," said Toro. "And my throat ain't drier than your back now, Don Jimmy; so you can put your clothes on and listen. They're going to bust the mine this afternoon—that's what they're going to do; and they'd knife me if they knew I was letting on."

"What?" cried Jimmy.

"It's a fact," said Toro, dropping the towel and feeling for a cigarette. "They're all so mighty well sure they won't be let go down to Bavaro for the Saint Gavino kick-up to-morrow that they've settled to do that. If there ain't no portering to do, they'll be let go. That's how they look at it. They don't care, not a peseta between[Pg 13] 'em, how much it costs the company to get the machine put right again; not them skunks don't. What they want is to have a twelve-hour go at the wine in the valley. You won't tell of me, Don Jimmy?"

"S—s—snakes!" said Jimmy.

Then he had started to run from the Lago Frio, with his coat on his arm. Dressing was a quick job in those wilds, where at midday in summer one didn't want much clothing.

"No, I won't let on!" he had cried back over his shoulder.

Toro, the Cuban kiddy, sat down on the margin of the cold blue lake and finished his cigarette reflectively. White folks, especially white English-speaking ones, were rather unsatisfactory. He liked them, because as a rule he could trust them. But Don Jimmy needn't have hurried away like that. He, Toro, hoped to have had licence to draw his pay for fully another hour's enjoyable idleness. As things were, however, Don Alonso, the foreman, would be sure to be down on him if he were two minutes after Don Jimmy among the red-earth heaps and the galvanised shanties of the calamine mine on its perch eight hundred feet sheer above the Vega Verde.

Jim Cayley was a few moments late for the soup after all.

"I s—s—say!" he began, as he bounced into the room.

"Say nothing, my lad!" exclaimed Don Alfredo, looking up from his newspaper.[Pg 14]

[Words missing in original] mail had just arrived—an eight-mile climb, made daily, both ways, by one of the gang.

Mrs. Jumbo, the moustached old Spanish lady who looked after the house, put his soup before Jimmy.

"Eat, my dear," she said in Spanish, caressing his damp hair—one of her many amiable yet detested little tricks, to signify her admiration of Jim's fresh complexion and general style of beauty.

"But it's—it's—it's most imp—p—p——"

Don Ferdinando set down his spoon. He also let the highly grave letter from London which he was reading slip into his soup.

"I tell you what, Cayley," he said, "if you don't crush this young brother of yours, I will. This is a matter of life or death, and I must have a clear head to think it out."

"I was only saying," cried Jim desperately. But his brother stopped him.

"Hold your tongue, Jim," he said. "We've worry enough to go on with just at present. I mean it, my lad. If you've anything important to proclaim, leave it to me to give you the tip when to splutter at it. I'm solemn."

When Don Alfredo said he was "solemn," it often meant that he was on the edge of a most unbrotherly rage. And so Jim concentrated upon his dinner. He made wry faces at Mrs. Jumbo and her strokings, and even found fault with the soup when she asked him sweetly if it were not excellent. All this to relieve his feelings.

The two engineers left Jim to finish his dinner by himself. Jim's renewed effort of "I say, Alf!" was quenched by the upraised hands of both engineers.

Outside they were met by Don Alonso, the foreman, a very smart and go-ahead fellow indeed, considering that he was a Spaniard.

"They'll strike, señores!" said Don Alonso, with a shrug. "It can't be helped, I'm afraid. It's all Domecq's doing, the scoundrel! Why didn't you dismiss him, Don Alfredo, after that affair of Moreno's death? There's not a doubt he killed Moreno, and he hasn't a spark of gratitude or goodness in his nature."

"He's a capable hand," said Alfred Cayley.

"Too much so, by half," said Don Ferdinando. "If he were off the mine, Elgos, we should run smoothly, eh?"

"I'll answer for that, señor," replied the foreman. "As it is, he plays his cards against mine. His influence is extraordinary. There'll not be a man here to-morrow; Saint Gavino will have all their time and money."

"You don't expect any active mischief, I hope?" suggested Don Ferdinando.

The foreman thought not. He had heard no word of any.

"Very well, then. I'll settle Domecq straight off," said Don Ferdinando.

He returned to the house and pocketed his revolver. They had to be prepared for all manner of emergencies in these wilds of Asturias,[Pg 16] especially on the eves and morrows of Saints' days. But it didn't at all follow that because Don Ferdinando pocketed his shooter he was likely to be called upon to use it.

The three were separating after this when a lad in a blue cotton jacket rose lazily from behind a heap of calamine just to the rear of them, and swung off towards the machinery on the edge of the precipice.

"Pedro!" called the foreman, and, returning, the lad was asked if he had been listening.

He vowed that such a thought had not entered his head. He had been asleep; that was all.

"Very good!" said the foreman. "You may go, and it's fifty cents off your wage list that your sleep out of season has cost you."

Discipline at the mine had to be of the strictest. Any laxity, and the laziest man was bound to start an epidemic of laziness.

Don Ferdinando set off for the Vega, eight hundred feet sheer below the mine. It was a ticklish zigzag, just to the left of the transporting machinery, with twenty places in which a slip would mean death.

Domecq was working down below, lading the stuff into bullock-carts.

Alfred Cayley disappeared into one of the upper galleries, to see how they were panning out.

The snow mountains and the afternoon sun looked down upon a very pleasing scene of industry—blue-jacketed workers and heaps of ore; and upon Jim Cayley also, who had enjoyed his[Pg 17] dinner so thoroughly that he didn't think so much as before about his rejected information.

But now again the Cuban kiddy drifted towards him, making for the zigzag.

Jim hailed him.

"Can't stop, Don Jimmy!" said Toro. But when he was some yards down, he beckoned to Jim, who quickly joined him.

They conferred on the edge of a ghastly precipice.

"I'm off down to tell Domecq that it's going to be done at two-thirty prompt," said Toro.

"What's going to be d—done?" asked Jimmy.

"What I told you about. They've cut the 'phone down to the 'llano' as a start. But that's nothing. You just go and squat by the engine and see what happens. Guess they'll not mind you."

To tell the truth, Jim was a trifle dazed. He didn't grapple the ins and outs of a conspiracy of Spanish miners just for the sake of a holiday. And as Toro couldn't wait (it was close on half-past two), Jim thought he might as well act on his advice. He liked to see the big buckets of ore swinging off into space from the mine level and making their fearful journey at a thrilling angle, down, down until, as mere specks, they reached the transport and washing department of the mine in the Vega. Two empty buckets came up as two full ones went down, travelling with a certain sublimity along the double rope of woven wire.

Jim sat down at a distance. He saw one cargo get right off—no more.

Then he noticed that the men engaged at the engine were confabulating. He saw a gleam of instruments. Also he saw another full bucket hitched on and sent down at the run. And then he saw the men furtively at work at something.

Suddenly the cable snapped, flew out, yards high!

Jim saw this—and something more. Looking instantly towards the Vega he saw the return bucket, hundreds of feet above the level, toss a somersault as it was freed of its tension and—this was horrible!—pitch a man head-foremost into the air.

He cried out at the sight, and so did the rascals who had done their rattening for a comparatively innocent purpose.

But when he and a dozen others had made the desperate descent of the zigzag, they found that the dead man was Domecq. Even the miners had no love for this arch-troubler, and, in trying to avoid Don Ferdinando, the sight of whom, coming down the track, had warned him of danger, Domecq had done the mine the best turn possible.

Toro's own warning was of course much too late.

The tragedy had a great effect. Saint Gavino was neglected after all, and it was in very humble spirits that the ringleaders of the plot confessed their sins and agreed to suffer the consequences.

Jim by-and-by tried to tell his brother and Don[Pg 19] Ferdinando that if only they had listened to him at dinner the "accident" might not have happened. But he stammered so much again (Don Ferdinando was as stern as a headmaster) that he shut up.

"It's—it's—nothing particu—ticu—ticular, Mr. Summerfield!" he explained.

Don Ferdinando was anything but depressed about Domecq's death; and Jim didn't want to damp his spirits. Of course, if Domecq had really killed another fellow only a few weeks ago, as was rumoured, he deserved the fate that had overtaken him.

III

A VERY NARROW SHAVE

One winter's day in San Francisco my friend Halley, an enthusiastic shot who had killed bears in India, came to me and said, "Let's go south. I'm tired of towns. Let's go south and have some real tip-top shooting."

In the matter of sport, California in those days—thirty years ago—differed widely from the California of to-day. Then, the sage brush of the foot-hills teemed with quail, and swans, geese, duck (canvas-back, mallard, teal, widgeon, and many other varieties) literally filled the lagoons and reed-beds, giving magnificent shooting as they flew in countless strings to and fro between the sea and the fresh water; whilst, farther inland, snipe were to be had in the swamps almost "for the asking." On the plains were antelope, and in the hills and in the Sierra Nevadas, deer and bears, both cinnamon and grizzly. Verily a sportsman's paradise!

The next day saw us on board the little Arizona, bound for San Pedro, a forty-hours' trip down the coast. We took with us only shot-guns, meaning to try for nothing but small game. At San Pedro, the port for Los Angeles (Puebla[Pg 21] de los Angeles, the "Town of the Angels"), we landed, and after a few days' camping by some lagoons near the sea, where we shot more duck than could easily be disposed of, we made our way to that little old Spanish settlement, where we hired a horse and buggy to take us inland.

Our first stopping-place was at a sheep-ranche, about fifty miles from Los Angeles, a very beautiful property, well grassed and watered, and consisting chiefly of great plains through which flowed a crystal-clear river, and surrounded on very side by the most picturesque of hills, 1,000 to 1,500 feet in height.

The ranche was owned by a Scotsman, and his "weather-board" house was new and comfortable, but we found ourselves at the mercy of the most conservative of Chinese cooks, whom no blandishments could induce to give us at our meals any of the duck or snipe we shot, but who stuck with unwearying persistency to boiled pork and beans. And on boiled pork and beans he rang the changes, morning, noon, and night; that is to say, sometimes it was hot, and sometimes it was cold, but it was ever boiled pork and beans. At its best it is not a diet to dream about (though I found that a good deal of dreaming could be done upon it), and as we fancied, after a few days, that any attraction which it might originally have possessed had quite faded and died, we resolved to push on elsewhere.

The following night we reached a little place at the foot of the higher mountains called[Pg 22] Temescal, a very diminutive place, consisting, indeed, of but one small house. The surroundings, however, were very beautiful, and the presence of a hot sulphur-spring, bubbling up in the scrub not one hundred yards from the house, and making a most inviting natural bath, coupled with the favourable reports of game of all kinds to be got, induced us to stop. And life was very pleasant there in the crisp dry air, for the quail shooting was good, the scenery and weather perfect, everything fresh and green and newly washed by a two days' rain, the food well cooked, and, nightly, after our day's shooting, we rolled into the sulphur-spring and luxuriated in the hot water.

But Halley's soul began to pine for higher things, for bigger game than quail and duck. "Look here," he said to me one day, "this is all very well, you know, but why shouldn't we go after the deer amongst the hills? We've got some cartridges loaded with buckshot. And, my word! we might get a grizzly."

"All right," I said, "I'm on, as far as deer are concerned, but hang your grizzlies. I'm not going to tackle them with a shot-gun."

So it was arranged that next morning, before daylight, we should go, with a boy to guide us, up one of the numerous cañons in the mountains, to a place where we were assured deer came down to drink.

It was a cold, clear, frosty morning when we started, the stars throbbing and winking as they[Pg 23] seem to do only during frost, and we toiled, not particularly gaily, up the bed of a creek, stumbling in the darkness and barking our shins over more boulders and big stones than one would have believed existed in all creation. Just before dawn, when the grey light was beginning to show us more clearly where we were going, we saw in the sand of the creek fresh tracks of a large bear, the water only then beginning to ooze into the prints left by his great feet, and I can hardly say that I gazed on them with the amount of enthusiasm that Halley professed to feel.

But bear was not in our contract, and we hurried on another half-mile or so, for already we were late if we meant to get the deer as they came to drink; and presently, on coming to a likely spot, where the cañon forked, Halley said, "This looks good enough. I'll stop here and send the boy back; you can go up the fork about half a mile and try there."

And on I went, at last squatting down to wait behind a clump of manzanita scrub, close to a small pool where the creek widened.

It was as gloomy and impressive a spot as one could find anywhere out of a picture by Doré. The sombre pines crowded in on the little stream, elbowing and whispering, leaving overhead but a gap of clear sky; on either hand the rugged sides of the cañon sloped steeply up amongst the timber and thick undergrowth, and never the note of a bird broke a silence which seemed only to be emphasised by the faint sough of the wind in the[Pg 24] tree tops. Minute dragged into minute, yet no deer came stealing down to drink, and rapidly the stillness and heart-chilling gloom were getting on my nerves; when, far up the steep side of the cañon opposite to me there came a faint sound, and a small stone trickled hurriedly down into the water.

"At last!" I thought. "At last!" And with a thumping heart and eager eye I crouched forward, ready to fire, yet feeling somewhat of a sneak and a coward at the thought that the poor beast had no chance of escape. Lower and nearer came the sound of the something still to me invisible, but the sound, slight though it was, gave, somehow, the impression of bulk, and the strange, subdued, half-grunting snuffle was puzzling to senses on the alert for deer. Lower and nearer, and then—out into the open by the shallow water he strolled—no deer, but a great grizzly.

My first instinct was to fire and "chance it," but then in stepped discretion (funk, if you will), and I remembered that at fifteen or twenty yards buckshot would serve no end but to wound and rouse to fury such an animal as a grizzly, who, perhaps of all wild beasts, is the most tenacious of life; and I remembered, too, tales told by Californians of death, or ghastly wounds, inflicted by grizzlies.

My finger left the trigger, and I sat down—discreetly, and with no unnecessary noise. He was not in a hurry, but rooted about sedately amongst the undergrowth, now and again [Pg 25]throwing up his muzzle and sniffing the air in a way that made me not unthankful that the faint breeze blew from him to me, and not in the contrary direction.

In due time—an age it seemed—after a false start or two, he went off up stream, and I, wisely concluding that this particular spot was, for the present, an unlikely one for deer, followed his example, and rejoined Halley, who was patiently waiting where we had parted.

"I've just seen a grizzly, Halley," I said.

"Have you?" he almost yelled in his excitement. "Come on! We'll get him."

"I don't think I want any more of him," said I, with becoming modesty. "I'm going to see if I can't stalk a deer amongst the hills. They're more in my line, I think."

Halley looked at me—pity, a rather galling pity, in his eye—and, turning, went off alone after the bear, muttering to himself, whilst I kept on my course downstream, over the boulders, certain in my own mind that no more would be seen of that bear, and keeping a sharp look-out on the surrounding country in case any deer should show themselves.

I had gone barely half a mile when, on the spur of a hill, a long way off, I spotted a couple of deer browsing on the short grass, and I was on the point of starting what would have been a long and difficult, but very pretty, stalk when I heard a noise behind me.

Looking back, I saw Halley flying from boulder[Pg 26] to boulder, travelling as if to "make time" were the one and only object of his life—running after a fashion that a man does but seldom.

I waited till he was close to me, till his wild eyes and gasping mouth bred in me some of his panic, and then, after a hurried glance up the creek, I, too, turned and fled for my life.

For there, lumbering and rolling heavily along, came the bear, gaining at every stride, though evidently sorely hurt in one shoulder. But my flight ended almost as it began, for a boulder, more rugged than its fellows, caught my toe and sent me sprawling, gun and cartridge-bag and self in an evil downfall.

I picked myself up and grabbed for my gun, and, even as I got to my feet, the racing Halley tripped and rolled over like a shot rabbit. It was too late for flight now, and I jumped for the nearest big boulder, scrambling up and facing round just in time to see the bear, fury in his eyes, raise his huge bulk and close with Halley, who was struggling to his feet. Before I could fire down came the great paw, and poor Halley collapsed, his head, mercifully, untouched, but the bone of the upper arm showing through the torn cloth and streaming blood.

I fired ere the brute could damage him further, fired my second barrel almost with the first, but with no apparent result except to rouse the animal to yet greater fury, and he turned, wild with rage, and came at me. A miserably insignificant pebble my boulder seemed then, and I remember vaguely [Pg 27]and hopelessly wondering why I hadn't climbed a tree. But there was small time for speculation, as I hurriedly, and with hands that seemed to be "all thumbs," tried to slip in a couple of fresh cartridges.

As is generally the case when one is in a tight place, one of the old cases jammed and would not come out—they had been refilled, and had, besides, been wet a few days before, and my hands were clumsy in my haste—and so, finally, I had to snap up the breech on but one fresh cartridge, throw up the gun, and fire, as the bear was within ten feet of me.

I fired, more by good luck, I think, than anything else, down his great, red, gaping mouth, and jumped for life as he crashed on to the rock where I had stood, crashed and lay, furiously struggling, the blood pouring from his mouth and throat, for the buckshot, at quarters so close, had inflicted a wound ten times more severe than would have been caused by a bullet.

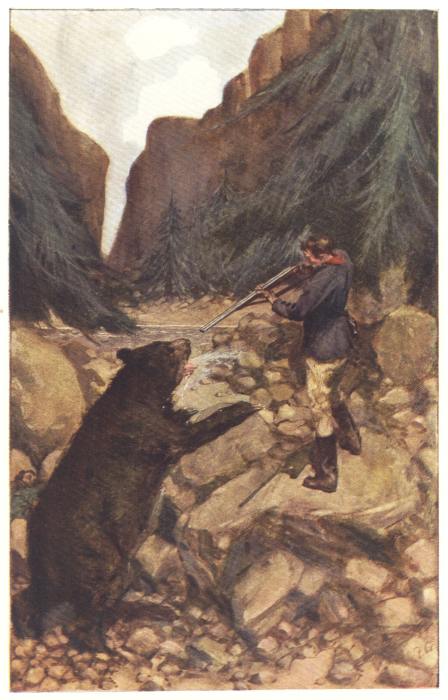

I FIRED DOWN HIS GREAT, RED, GAPING MOUTH AND JUMPED FOR LIFE.

It was quite evident that the bear was done, but, for the sake of safety—it does not do to leave anything to chance with such an animal—I put two more shots into his head, and he ceased to struggle, a great shudder passed over his enormous bulk, the muscles relaxed, and he lay dead.

Then I hurried to where Halley lay. Poor chap! He was far spent, and quite unconscious, nor was I doctor enough to know whether his wounds were likely to be fatal, and my very ignorance made them seem the more terrible. I[Pg 28] tore my shirt into bandages, and did what I could for him, succeeding after a time in stopping the worst of the bleeding; but I could see very plainly that the left shoulder was terribly shattered, and I thought, with a groan, of the fifty weary miles that one must send for a doctor.

Presently he began to come to, and I got him to swallow a little brandy from his flask, which revived him, and before long, after putting my coat beneath his head, I left him and started for help.

It was a nightmare, that run. Remorse tore me for having let him start after the bear alone, and never could I get from my mind the horrible dread that the slipping of one of my amateur bandages might re-start the bleeding, and that I should return to find only the lifeless body of my friend; ever the fear was present that in the terribly rough bed of the creek I might sprain my ankle, and so fail to bring help ere it was too late. At times, too, my overstrung nerves were jarred by some sudden sound in the undergrowth, or the stump of a tree on a hillside would startle me by so exact a likeness to a bear, sitting up watching me, as to suggest to my mind the probability of another bear finding and mauling Halley whilst he lay helpless and alone.

But if my nerves were shaken, my muscles and wind were in good order, and not even the most morbid self-consciousness could find fault with the time spent on the journey. Luck favoured me, too, to this extent, that almost as I got on to[Pg 29] the road, or, rather, track, about a mile from the inn, I met, driving a buggy, and bound for Los Angeles, a man whose acquaintance we had made a few days before, and who, with much lurid language, had warned us against going after bear.

His remarks now were more forcible than soothing or complimentary when I explained the matter to him during the drive to the inn, where he dropped me, himself going on for the doctor as fast as two horses could travel.

It did not take us long to improvise a stretcher, and, with the willing help of two men and of the landlady, in about three hours we had Halley in his room. But a hideous walk it was down the cañon, every step we made wringing a groan from the poor fellow except when he fainted from pain.

The doctor did not arrive till the following morning, by which time the wounds were in a dreadful condition, and it was touch and go for life, while the doctor at first had no hope of saving the arm. But youth, and time, and a strong constitution pulled him through, and in a couple of weeks he was strong enough to describe to me how he had fallen in with the bear.

He had gone, it seemed, not to where I had seen the animal, but up a branch cañon. At no great distance up he met the beast, making its way leisurely across the creek, and, in his excitement, he fired both barrels into the bear's shoulder; and then the same thing happened that had happened to me—those refilled cartridges had jammed, and there was nothing for it but to[Pg 30] run for his life. Luckily he had badly lamed the animal, or his chance of escape would have been nil, and, as it was, in another two hundred yards the bear would have been into him.

Some days after the accident, the first day that I could leave Halley's bedside, I went out to see if it was possible to get the skin of the bear, but I found it badly torn, maybe by coyotes, and all that could be got as trophies were his claws.

There they are now, hanging over the pipe-rack by the fireplace in my snuggery in dear old England.

IV

AN ADVENTURE IN ITALY

A Fourth-form Boy's Holiday Yarn

Last winter I had a stroke of real good luck. As a rule I'm not one of the lucky ones; but this time, for once, Fortune smiled on me—as old Crabtree says, when he twigs some slip in my exercise, but can't be quite sure that I had borrowed another fellow's, just to see how much better mine was than his!

It was this way. It was a beastly wet afternoon, and the Head wouldn't give me leave to go to the village. But I was bound to go, for I wanted some wire to finish a cage I was making for my dormouse, who was running loose in my play-box and making everything in an awful mess. So I slipped out, and, of course, got soaked.

I couldn't go and change when I came back with the wire, as Crabtree would then have twigged that I'd been out in the rain. So the end of it was that I caught a chill and had to go into the infirmary. I was awfully bad for a bit, and went off my head, I suppose—for the mater came and I didn't know her till I got better, and then she told me that the doctor had said I must go to Italy for the winter, as my lungs were very weak,[Pg 32] and she was going with me, and we should be there till April or May.

The Head told me he hoped I would take some books with me, and do a little reading when I was better. You bet I did! The mater packed them, but they weren't much, the worse for wear when I brought them back to St. Margaret's again.

The Head also hoped I would use the opportunity to study Italian antiquities. I did take a look at some, but didn't think much of them. They took me at Rome to the Tarpeian Rock, but it wouldn't hurt a kid to be chucked down there, let alone a traitor; and the Coliseum wanted livening up with Buffalo Bill. The only antiquities I really cared for were the old corpses and bones of the Capucini, which everybody knows about, but has not had the luck to see as I did.

But I had a walk round so as to be able to say I'd seen the other things, and brag about them when they turned up in Virgil or Livy, and set old Crabtree right when he came a cropper over them, presuming on our knowing less than he did. There was too much for a fellow to do for him to waste time over such rot as antiquities. You can always find as many antiquities as you want in Smith's Dictionary.

Before I went I swapped my dormouse with Jones ma. for his revolver. I couldn't take the dormouse with me, and I knew you were bound to have a revolver when you risked your life among foreigners and brigands, which Italy is full of, as everybody knows. Where should I be if I fell in[Pg 33] with a crew of them and hadn't a revolver? Besides, I was responsible for the mater.

Jones ma.'s revolver wouldn't shoot, but it looked all right, and no brigand will wait to see if your revolver will go off when you present it at his head. All you have to do is to shout "Hands up!" and he either lets you take all the diamonds and things he has stolen from fools who hadn't revolvers, or runs away. I cut a slit in my trousers behind, and sewed in a pocket, and practised lugging the revolver out in a jiffy, and getting a bead on an imaginary brigand. I was pretty spry at it, and knew I should be all right. And it was just that revolver which saved me, as you will see.

We travelled through Paris and a lot of other places, stopping at most of them, for I was still rather weak, and the mater was fussy about my overdoing it till we settled down at Sorrento. That's a place on the Bay of Naples, and just the loveliest bit of it—oranges everywhere. It's ten miles from Castellamare, the nearest railway-station, but the drive along the edge of the bay, on a road cut into the cliffs hundreds of feet up, makes you feel like heaven.

Vesuvius is quite near too, only that was no good, for the mater wouldn't let me go there, which was a most aggravating shame, and a terrible waste of opportunity, which I told her she would regret ever after. The crater was as jolly as could be, making no end of a smoke, and pouring out lava like a regular old smelting-furnace;[Pg 34] but she said she wasn't going to bring me out to Italy to cure a cold, only to have me burnt up like one of those Johnnies they show you at Pompeii who were caught years and years ago. As if I should have been such an ass as to get caught myself.

What I was going to tell you about, however, was this. We had been at Sorrento six or seven weeks, and I'd got to know the places round that were worth seeing, and a lot of the people too, who jabbered at you thirteen to the dozen, and only laughed when you couldn't make out what they were saying. I'd picked up some of their words—enough to get what I wanted with, and that's the best way to learn a language; a jolly sight better than fagging along with a grammar and stupid exercises, which are only full of things no fellow wants.

So the mater had got used to letting me go about alone, and one morning she found she wanted some things from Naples, and wasn't feeling up to the journey. She wondered at breakfast if she could dare to let me go for her. I didn't seem eager, for if they think you particularly want to do a thing, they are sure to try to stop you. So I sat quiet, though I could hardly swallow my coffee—I was so keen to go.

However, she wanted the things badly, and at last she had to ask me if I would go for her. It's always so: it doesn't matter how badly you want a thing, but when the mater or sister or aunt think they want some idiotic trash that everybody in his[Pg 35] senses would rather be without, you've simply got to fetch it for them, or they'll die.

She rather spoilt it by giving me half an hour's jawing as to what I was to do, to take care of this or that, and not to get lost or miss the train—you know how they go on and spoil a fellow's pleasure—as if I couldn't go to Naples and back without a woman having to tell me how to do it. I stood it all patiently though, for the sake of what was coming, and a high old time I had in Naples that day, I can tell you.

I nearly missed my train back, catching it only by the skin of my teeth, and when I reached Castellamare I bargained with a driver-fellow to take me to Sorrento for seven francs. He could speak English a bit. The mater had told me the fare for a carriage and two mules would be eight or ten francs; but I soon let him see that I wasn't going to be put on like that, and as I was firm he had to come down to seven, and a pourboire, which is what we call a tip. So, ordering him to wake his mules up and drive quick, for the January afternoon was getting on, I settled down thoroughly to enjoy the ride home.

I have already told you how the road follows the coast-line, high up the cliffs, so that you look down hundreds of feet, almost sheer on to the waves dashing against the rocks below. There's nothing but a low wall to prevent you pitching bang over and dashing yourself to bits, if you had an accident. There are two or three villages between Castellamare and Sorrento, and generally[Pg 36] a lot of traffic; but, as it happened, we didn't pass or meet much that afternoon; I suppose because it was getting late.

The driver was chattering like a magpie about the swell villas and places we could see here and there white against the dark trees, but I wasn't paying much attention, and at last he shut up.

There's one bit of the road which always gave me the creeps, for it's where a man cut his son's throat and threw him over the cliff, two or three years ago, for the sake of his insurance money. I was thinking about this, and almost wishing some one was with me after all—for there wasn't a soul in sight—when my heart gave a jump as the driver suddenly, at this very bit, pulled up, and, turning round, said with a fiendish grin—

"You pay me 'leven francs for ze drive, signor."

"Eleven? No, seven. You said seven."

"Signor meestakes. 'Leven francs, signor," and he opened the dirty fingers of his left hand twice, and held up a thumb that looked as if it hadn't been washed since he was born.

"Seven," I firmly replied. "Not a centime more. Drive on!"

"Ze signor will pay 'leven francs," he fiercely persisted, "seven for ze driver and four for ze cicerone, ze guide."

"What guide? I've had no guide."

"Me, signor. I am ze guide. 'Ave I not been telling of ze beautiful villas and ze countrie?"

"You weren't asked to," I retorted. "Nobody wanted it."

"Zat does not mattaire. Ze signor will pay for ze cicerone."

"I'll see you hanged first."

"Zen we shall see."

He turned his mules to the side of the road next the precipice. I caught a glimpse of an ugly knife in the handkerchief round his waist. In a moment I had whipped out my revolver, and levelled it straight for his head. My word, how startled he was!

"Now drive on," I said.

He did, without a word, but turning as white as a sheet,—and made his old mules fly as if they'd got Vesuvius a foot behind them all the way. I kept my revolver ready till we came to Meta, after which there are plenty of houses.

When we drew up at the hotel I gave him his seven francs, and told him to think himself lucky that I didn't hand him over to the police. He had partly recovered by then, and had the cheek to grin and say—

"Ah, ze signor ees a genteelman,—he will give a poor Italiano a pourboire."

But I didn't.

I've often wondered since if he really meant to do for me. Anyhow, my revolver saved me, and was worth a dormouse.

V

THE TAPU-TREE

"The fish is just about cooked," announced Fred Elliot, peering into the big "billy" slung over their camp fire. "Now, if Dick would only hurry up with the water for the tea, I'd have supper ready in no time."

"I wish supper were over and we well on our way to the surveyor's camp at the other side of the lake," was the impatient rejoinder of Hugh Jervois, Dick's big brother. "This place isn't healthy for us after what happened to-day." And he applied himself still more vigorously to his task of putting into marching order the tent and various other accessories of their holiday "camping out" beside a remote and rarely visited New Zealand lake.

"But surely that Maori Johnny wouldn't dare to do any of us a mischief in cold blood?" cried Fred.

"The police aren't exactly within coo-ee in these wilds, and you must remember that your Maori Johnny happens to be Horoeka the tohunga (tohunga = wizard priest), who has got the Aohanga Maoris at his beck and call. The surveyors say he is stirring up his tribe to make trouble over the survey of the Ngotu block, and[Pg 39] they had some hair-raising stories to tell me of his superstitious cruelty. He is really half-crazed with fanaticism, they say, and if you bump up against any of his rotten notions, he'll stick at nothing in the way of vengeance. As you saw yourself, he'd have killed Dick this afternoon hadn't we two been there to chip in."

"There's no doubt about that," allowed Fred. "It was no end unlucky that he should have caught Dick in the very act."

"Oh, if I had only come in time to prevent the youngster hacking out his name on that tree of all trees in the bush," groaned Hugh. "The most tremendously tapu (tapu = sacred) thing in all New Zealand, in the Aohanga Maoris' eyes!"

"But how was Dick to know?" urged Fred. "It just looked like any other tree; and who was to guess the meaning of the rubbishy bits of sticks and stones lying at the bottom of it? Oh, it's just too beastly that for such a trifle we've got to skip out of this jolly place! And there are those monster trout in the bay below almost fighting to be first on one's hook! And there's——"

"I say, what on earth can be keeping Dick?" broke in Hugh with startling abruptness. "Suppose that Maori ruffian——" and a sudden fear sent him racing down the bush-covered slope with Fred Elliot at his heels.

"Dick! Coo-ee! Dick!" Their voices woke echoes in the silent bush, but no answer came to them. And there was no Dick at the little spring trickling into the lake.

But the boy's hat lay on the ground beside his upturned "billy," and the fern about the spring looked as if it had been much trampled upon.

"There has been a struggle here," said Hugh Jervois, his face showing white beneath its tan. Stooping, he picked up a scrap of dyed flax and held it out to Fred Elliot.

"It's a bit of the fringe of the mat Horoeka was wearing this afternoon," he said quietly. "The Maori must have stolen on Dick while he was filling his 'billy,' and carried him off. A thirteen-year-old boy would be a mere baby in the hands of that big, strong savage, and he could easily stifle his cries."

"He would not dare to harm Dick!" cried Fred passionately.

Dick's brother said nothing, but his eyes eagerly searched the trampled ground and the undergrowth about the spring.

"Look! There is where the scoundrel has gone back into the bush with Dick," he cried. "The trail is distinct." And he dashed forward into the dense undergrowth, followed by Fred.

The trail was of the shortest and landed them on a well-beaten Maori track leading up through the bush.

The two young men, following this track at a run, found that it brought them, at the end of a mile or so, to the chief kainga, or village, of the Aohanga Maoris.

"It looks as if we had run our fox to earth," cried Fred exultingly, as they made for the[Pg 41] gateway of the high wooden stockade—relic of the old fighting days—which surrounded the kainga.

The Maoris within the kainga met them with sullen looks, for their soreness of feeling over the Government surveys now going on in their district had made them unfriendly to white faces. But it was impossible to doubt that they were speaking truth when, in answer to Hugh's anxious questioning, they declared that no pakeha (white man) had been near the kainga, and that they had seen nothing of Horoeka, their tohunga, since noon that day. They suggested indifferently that the white boy must have lost himself in the bush, and, at the same time, gave a sullen refusal to assist in searching for him.

Before the two young men wrathfully turned their backs on the kainga, Hugh, who had a very fair knowledge of the Maori tongue, warned the natives that the pakeha law would punish them severely if they knowingly allowed his young brother to be harmed. But they only replied with insolent laughter.

For the next two hours Hugh and Fred desperately scoured the bush, shouting aloud at intervals on the off-chance that Dick might hear and be able to send them some guiding cry in answer. But the only result of their labours was that they nearly got "bushed" themselves, and at last the fall of night made the absurdity of further search clear to them.

Groping their way back to their broken-up camp, they lighted the lantern and got together a[Pg 42] meal of sorts. But Hugh Jervois could not eat while racked by the horrible uncertainty of his brother's fate, and he waited impatiently for the moon to rise to let him renew his apparently hopeless quest.

Then, while Fred Elliot was speeding on a seven miles' tramp round the shore of the lake to the surveyors' camp to invoke the aid of the only other white men in that remote part of the country, Hugh Jervois had made his way to the Maori kainga. "It's my best chance of finding Dick," he had said to Fred. "Horoeka is sure to have returned to the kainga by this time, and, by cunning or by force, I'll get out of that crazy ruffian what he has done with my brother."

Reconnoitring the kainga in the light of the risen moon Hugh stealthily approached the palisade surrounding it. This was very old and broken in many places, and, peering through a hole in it, the young man saw a group of women and children lounging about the cooking-place in the centre of the marae or open space around which the wharés (huts) were ranged. From the biggest of those wharés came the sound of men's voices, one at a time, in loud and eager talk. At once Hugh realised that a council was being held in the wharé-runanga, the assembly-hall of the village, and he instinctively divined that the subjects under discussion were poor little Dick's "crime" and his punishment, past or to come.

Noiselessly skirting the palisade, Hugh came to a gap big enough to let him squeeze through.[Pg 43] Then he crept along between the palisade and the backs of the scattered wharés—very cautiously, for he dreaded being seen by the group about the fire—until at last he stood behind the big wharé-runanga. With his ear glued to its wall he listened to the excited speeches being delivered within, and to sounds indicating that drinking was also going on—whisky supplied from some illicit still, doubtless.

To his unspeakable thankfulness the young man gathered from the chance remarks of one of the speakers that Dick, alive and uninjured, had been brought by Horoeka into the kainga at nightfall, and was now shut up in one of the wharés. But a fierce speech of Horoeka's presently told the painfully interested eavesdropper that nothing less than death, attended by heathenish and gruesome ceremonies, would expiate the boy's outrage on the tapu-tree, in the tohunga's opinion.

The other Maori speakers would evidently have been satisfied to seek satisfaction in the shape of a money-compensation from the offender's family, or the paternally minded New Zealand Government. But, half-mad though he was, Horoeka's influence with his fellow-tribesmen was very great. The rude eloquence with which he painted the terrible evils that would certainly fall on them and theirs if the violation of so mighty a tapu was not avenged in blood, very soon had its effect on his superstitious hearers.

When he went on to assure them that the[Pg 44] pakehas would be unable to prove that the boy had not lost himself and perished in the bush, they withdrew all opposition to Horoeka's bloodthirsty demands, though these were rather dictated by his own crack-brained fancy than by Maori custom and tradition. Presently, indeed, it became evident to Hugh that, what with drink and their tohunga's wild oratory, the men were working themselves up into a fanatical frenzy that must speedily find vent in horrible action.

If Dick's life were to be saved he must be rescued at once! No time now to await Fred Elliot's return with the surveyors and their men! Hugh must save his brother single-handed. But how was he to do it? For him, unarmed and unbacked by an authoritative show of numbers, to attempt an open rescue would merely mean, in the natives' present state of mind, the death of both brothers.

"If the worst comes, I won't let Dick die alone," Hugh Jervois avowed. "But the worst shan't come. I must save Dick somehow."

He cast desperate glances around. They showed him that the marae was completely deserted now, the group about the cooking-place having retired into the wharés for the night. If he only knew which of those silent wharés held Dick, a rescue was possible. To blunder on the wrong wharé would only serve to arouse the kainga.

"Oh, if I only knew which! If I only knew which!" Hugh groaned in agony of mind. "And[Pg 45] any moment those fiends may come and drag him out to his death."

Just then, as if in answer to his unspoken prayer, an unexpected sound arose. Poor little Dick, in sore straits, was striving to keep up his courage by whistling "Soldiers of Our Queen!"

Hugh's heart leaped within him. The quavering boyish whistle came from the third wharé on his left, and, in an instant, he had reached the hut and was gently tapping on the door. Dick might not be alone, but that chance had to be risked, for time was very precious.

"It's Hugh, Dick," he whispered.

"Hugh! Oh, Hugh!" and in that choking cry Hugh could read the measure of his young brother's mental sufferings since he had last seen him.

In a moment he had severed the flax fastening of the door, and burst in to find Dick, securely tied hand and foot to a post in the centre of the wharé. Again Hugh's pocket-knife came into play, and Dick, freed of his bonds, fell, sobbing and crying, into his brother's arms.

"Hush, Dick! No crying now!" whispered Hugh imperatively. "You've got to play the man a little longer yet. Follow me."

And the youngster, making a brave effort, pulled himself together and noiselessly stole out of the wharé after his brother.

But evil chance chose that moment for the breaking up of the excited council in the [Pg 46]wharé-runanga. Horoeka, stepping out into the marae to fetch his victim to the sacrifice, was just in time to see that victim disappearing round the corner of his prison-house. With a yell of rage and surprise he gave chase, his colleagues running and shouting at his heels.

Hugh Jervois, hearing them coming, abandoned hope for one instant. The next, he took heart again, for there beside him was the hole in the palisade through which he had crept into the kainga an hour before. In a twinkling he had pushed Dick through and followed himself. And as they crouched unseen outside, they heard the pursuit go wildly rushing past inside, heedless of the low gap in the stockade which had been the brothers' salvation.

"They'll be out upon us in a moment," cried Hugh. "Run, Dick! Run!"

Hand in hand they raced down the slope and plunged into the cover of the bush. Only just in time, however, for the next instant the moonlit slope beneath the kainga was alive with Maoris—men, women, and children—shouting and rushing about in a state of tremendous excitement. It was for Dick alone they hunted, not knowing he had a companion, and they were evidently mystified by the boy's swift disappearance.

Presently the brothers, lying low in a dense tangle of ferns and creepers, saw a number of the younger men, headed by Horoeka, streaming down the track leading to the lake. But after a little time they returned, somewhat sobered and[Pg 47] crestfallen, and rejoined the others, who had meanwhile gone inside the kainga.

Then, feeling sure that the coast was clear, the brothers ventured to steal cautiously out of earshot of the enemy and make their way down through the bush to the shores of the lake. There they were greeted with the welcome sound of oars, and, shooting swiftly towards them through the moonlit waters, they saw the surveyors' boat, with Fred Elliot and half a dozen others in her.

"You see they are trying to carry off the thing just in the way I told you they'd do," said the head surveyor to Hugh Jervois after their denunciatory visit to the kainga in the early morning. "Horoeka, the arch-offender, has disappeared into remoter wilds, and the others lay the blame of it all on Horoeka."

"Yes," responded Hugh, "and even then the beggars have the impudence to swear, in the teeth of their talk last night in their wharé-runanga, that Horoeka only meant to give the pakeha boy a good fright because he had done a mischief to the very tapu-tree in which lives the spirit of the tribe's great ancestor."

"Well," said the surveyor, "we've managed to give the tribe's young men and elders a good fright to-day, anyhow. My word! but their faces were a picture as we lovingly dwelt on the pains and penalties awaiting them for their share in their tohunga's outrage on your brother. I'll tell you what it is, Jervois. Horoeka has to keep in hiding[Pg 48] for his own sake, and these beggars will have their hands so full, with a nice little charge like this to meet, that they won't care to make trouble for us when we come to the survey of the Ngotu block."

"It's an ill wind that blows nobody good," laughed Hugh. "But, all the same, Dick may be excused for thinking that your unobstructed survey has been dearly bought with the most horrid experience he is likely ever to have in his life."

VI

SOME PANTHER STORIES

The pages of literature devoted to sport and the hunting of wild game teem with stories and instances of occasions when the hunted, driven to desperation and enraged to ferocity by wounds, turns, and itself becomes the hunter and the avenger of its own hurts.

Of all wild animals perhaps the most vindictive, the most cunning, and the most dangerous to hunt is the panther; indeed, nine out of ten who have had experience of shooting in all parts of the world will concede that the pursuit of these animals is really more fraught with danger and hazard than that of even the tiger, lion, and elephant; and the following is one of many instances, of yearly occurrence, of the man behind the rifle not having it all his own way when drawn in actual combat against the denizens of the jungles.

It was drawing on towards the hot weather when my friend Blake, who had been very seedy, thought that I might try to get a few days' leave and join him in a small shooting expedition into the jungles of southern India, where he was sure he would recover his lost strength and vitality, and[Pg 50] so face the coming hot weather with a fair amount of equanimity.

The necessary leave being forthcoming, we consulted maps, arranged ways and means for a fortnight's camp—always a considerable thing in India—and, accompanied by two Sikhs and a Rajput orderly, with horses, guns, rifles, and dogs galore, after a day's journey in the train reached the place from whence the remainder of our journey was to be done by road.

Our destination was a place called Bokeir, and constituted what is known in India as a jargir, that is a tract of land which, together with the rent roll and tribute of the villages therein comprised, is given to men whose services have deserved well of their State. Such are known as jargirdars, and enjoy almost sovereign state in their little domains, receiving absolutely feudal devotion from their tenantry and dependants.

We pitched our camp in the midst of a magnificent grove of mango-trees, which at the time of the year were covered with the green fruit. I was told that before the famine of 1898-99 the grove comprised over two thousand trees; but at present there are about half that number.

We then received and returned visits with the jargirdar, a Mahratta, and an exceedingly courteous and dignified man. We asked for and received permission to shoot in his country, and in addition everything possible was done for our comfort, supplies of every description being at once forthcoming. So tenacious were the people[Pg 51] of the villages in their devotion to their chief that not a hand would have been raised to help us nor a blade of grass given without an order from the head of this tiny State.

Then we commenced our jungle campaign. The footmarks of a tiger and tigress, of a very large panther, of bear, sambar, and blue bull abounded in a wooded valley some six miles from the camp. We tied up young buffalo-calves, to attract the large Felidæ, and ultimately met with success, for one morning we were having breakfast early when in trotted one of our Sikhs who had gone before the peep of dawn to look at the "kills." He reported that one of the calves had been killed at five that morning; so, putting a hasty conclusion to our breakfast, we called for horses, saw to our rifles and cartridges, and rode away to the scene of the early morning tragedy.

Arrived at a village called Sirpali, we left our horses and proceeded on foot up a lovely wooded valley filled with the bastard teak, the strong-smelling moha-tree (from which the bears of these parts receive their chief sustenance), the giant mango, pipal and banyan.

The awesome silence of the dense forest reigned supreme in the noonday heat. The whispered consultations and the occasional footfall of some one of the party on a dry teak-leaf seemed to echo for miles and to break rudely the well-nigh appalling quiet of the jungle. Here and there, sometimes crossing our path, were the fresh footprints of deer and of antelope, of pig[Pg 52] and the lordly sambar stag that had passed this way last night to drink at a time when the presence of man does not disturb the domain of the beasts of the forest. Here was a tree with deep, clean marks all the way up its trunk, from which the sap was still oozing, showing us that for some purpose a bear had climbed up it in the early morning, though why we could not tell, as there was neither fruit nor leaf on its bare branches.

And then a turn in the path brought us to the kill, to the tragedy of a few hours ago. Surely this is the work of a tiger—the broken neck, the tail bitten off and flung aside, the hind-quarters partly consumed? No, for there are only the marks of a panther's pads and none of any tiger. They lead away into some dense jungle in front, and from here we decide to work.

Leaving the beaters here, we went by a circuitous way until we arrived two or three hundred yards ahead of the direction the beat would take. Here we were nonplussed, for the jungle was so dense and the configuration of the ground such that there were many chances in favour of any animal that might be before the beat being able to make a very good bid for eluding the enemy.

However, we came to a place which appeared as good as any, and, as both of us seemed to think that it would suit himself exceedingly well, we drew lots, and, contrary to my usual luck, I drew the longer of the two pieces of grass and decided to remain, while Blake took up his position about fifty yards to my left.

When shooting in the jungle, it is the practice of most to shoot from a tree, not so much from a sense of added security—as both bears and panthers think little of running up a tree and mauling you there—but from the better field of view you get. Accordingly, as there was a small tree near, I ascended, and, because the footing was precarious and the position unfavourable for a good shot, I buckled myself to a bough by means of one of my stirrup-leathers. This is a device, by the way, which I can most thoroughly recommend to all, for it as often as not gives you free use of your arms, and even enables you to swing right round to score a shot at a running object.

I had not long disposed myself thus, when the beat sprang into life with a suddenness and intensity which made me pretty sure that they had disturbed some animal. The shouting, cat-calling, and tom-tomming increased in violence, when all at once I heard a quick and rather hurried tread, tread, tread over the dry teak-leaves, and, looking that way, out of the dense jungle into the sunlit glade before me came a large panther.

I put up my rifle. It saw me, and crouched head on in some long, dry grass. It was a difficult shot, but I hazarded it.

The beast turned and went up the bank to my right. "Missed," thought I, and let it have my left barrel as it was moving past. "Missed again," I thought, and growled inwardly.

I caught another glimpse of the brute as it went[Pg 54] behind me, and to my relief a crimson patch had appeared on its right side. I howled to the beaters, who had now approached, to be careful, as a wounded panther was in front of them, and, Blake joining me, we made them all sit down to keep them out of harm's way.

Accompanied by the two Sikhs, Blake and I began to stalk the wounded animal. Where had it gone? Into that dense bit of jungle in front, apparently. So we began to cast around among the leaves. They at first yielded no betraying footmarks, but at last a leaf was found with a large spot of frothy blood, showing the animal's injury to have been through the lungs.

"Put a man up that tree," I said; "the animal is badly hit and cannot have gone far." But my advice was ignored.

Then from a spot over which I had walked not a minute before there came a rush and a roar. Swinging round, I saw ten paces off Blake raise his rifle and fire two barrels, but, alas! apparently without result. Down he went before the savage rush of the beast, which began to worry him.

Blake had fallen back on his elbows, and in the curve of his neck and right shoulder I could just see, though so near, the dark-spotted body of the panther. There was no time to lose. "Can I hit it without killing Blake?" I thought in an agony of uncertainty, but the hazard followed quick upon the thought, and bang, bang, went my two barrels. At the same time the Sikh dafadar, Gopal Singh, with all the characteristic bravery[Pg 55] of this magnificent race, ran in and beat the animal about the head with the butt-end of Blake's shot-gun, which he was carrying at the time.

All this was too much for the panther, who then left Blake and shambled away. I threw down my own rifle and ran to Blake's assistance, when the panther stopped and half turned towards us.

"He's coming at me again," Blake cried, and covered his face with his hands. We were all unarmed; like a fool I had left my rifle ten paces behind me, the Sikh's shot-gun was smashed to splinters, and Blake's rifle had fallen nobody knew where during the mêlée. But, fortunately for us, and more especially for me, who was then nearest her, the panther seemed to think better of it, and tumbled off into the jungle, as far as I could see very badly knocked about.

Then we attended to Blake's injuries, which consisted of a large piece torn from his left forearm, three great teeth-marks in his left thigh, and claw-marks all over his left calf. He was very brave, though bleeding a lot, and walked with our assistance towards the village until one of the orderlies galloped up with the "charpai," or native bed, I had sent for immediately the accident had occurred. Then on to camp, where I re-dressed his wounds, sprinkling them with boracic acid, which was, foolishly, all we had provided in the way of antiseptics.

Then a "palki" or palankin arrived, lent by the jargirdar, who had also sent his ten private carriers, and, accompanied by the dafadar, we[Pg 56] started for the railway, the nearest point of which was forty miles away, and reached it at five the next morning, having experienced thirteen hours of anxiety, dead weariness, exhausted palankin men, bad and in some places non-existent roads, and, to crown all, one river to ford.

Blake has happily survived his injuries—always severe when inflicted by panthers, as these animals' teeth and claws, from their habit of killing their prey and leaving it exposed for a day to the Indian sun, seldom fails to induce blood-poisoning, which few, if any, have been known to survive.

The panther was found next day, quite dead, with three bullet-wounds in her—one in the chest, one through the ribs, and one through the body from the front left ribs to the left haunch; and that she was able to do all the damage she did testifies to the proverbial tenacity of life and ferocity of these animals. The native of India will tell you, "The tiger is a janwár (animal), but the panther he is a shaitán (devil)."

Mr. Dickson Price, who had a narrow escape from a panther in 1905, thus described the occurrence—

Owing to the stricter preservation of the jungles round Marpha, beasts of prey appear to have greatly increased in number the last year or so.

Last November a travelling pedlar was killed on a path close by; while this year more than twenty head of cattle have been killed by tigers[Pg 57] and panthers at Marpha and near by. This is a very serious loss to the people, who depend entirely upon their cattle for ploughing, etc.

On February 22, just after the mela, some villagers from Kareli—a village close to us—came to me asking me to shoot a tiger that had killed a fine plough-ox, and was causing great havoc.

On arriving at the spot where the kill was, an examination of the marks on the bullock showed that it was a panther and not a tiger that had been at work. The place was in sight of the village and on the skirt of a forest. We had a "machan" (platform) in a tree made, and at three o'clock in the afternoon I climbed up with my native shikari or hunter and watched and waited until dark.

About 8 p.m. it was pitch dark, and the animal could be heard munching beneath. I fired at a black object twice with no result, for we still heard the beast going on with his dinner. I found later I had fired at a bush, mistaking it for a panther in the darkness. The animal was either too hungry to notice the shot, or had mistaken the sound for thunder. Later on the moon rose, and at half-past three in the morning a third shot took effect, for the animal went off badly wounded. Some time before that a heavy thunderstorm had come on, but, sheltered beneath our rugs, we did not get really wet. We now slept, feeling our work was done. At sunrise the native hunter and I got down and examined the spot.

While we were looking at the blood-marks a[Pg 58] tremendous roar was heard close by, and my native shikari calling out, "Tiger! tiger! tiger!" bolted and ran off to the village as fast as his heels could carry him. I climbed back into the machan, to watch the development of events. After some time about sixteen villagers came out to help, and we slowly followed up the blood-trail.

After piercing the thick jungle for about two hundred yards, at times having to creep under the brushwood, we came to a narrow nala, or shallow watercourse with sandy bed, and we found out the cause of the constant growling we had heard. A tiger also was tracking the panther, who every now and then stood at bay and attacked it. After some time the tiger, no doubt hearing us, turned aside. Suddenly I saw the wounded animal scaling a tall and almost branchless tree, which appeared as though it must have been at some time struck by lightning. The panther, no doubt, hoped to escape all its enemies in that way. It went to the tip-top, about forty feet or fifty feet from the ground.

I fired, but the range was too long for my shot and ball gun. The firing frightened the panther, which fell in descending when some fifteen feet from the ground. We all tracked on, hoping to get a chance of a further shot.

At last we came to a deep and thickly wooded nala, or watercourse, which curved like a horseshoe. The panther entered the watercourse at the centre and turned along the bed to the left.[Pg 59] We turned to the right and skirted along the outside of the course, as it was not safe to go nearer. We all advanced until we nearly reached the right limit of the horseshoe bend, and then, leaving the trackers, I approached the watercourse, hearing the beast at the other end about two hundred yards away.

After waiting about twenty minutes looking for a spot to cross the deep nala it appears that the wounded animal slowly and silently doubled back along the densely wooded watercourse and suddenly sprang out at me. I fired and stepped back, falling, as I did so, into the watercourse. The next thing I remember was the panther seizing me by the arm and pulling me down as I arose, and beginning to claw my head.

Then I saw on top of the panther my little fox-terrier Toby, tearing hard at the neck of the beast. The panther then left mauling me to attack the dog. I somehow jumped up, leaped out of the watercourse, ran towards the villagers, and fell down. They placed me on a charpoi, or native bed, and carried me to my bungalow three miles away. Express messengers were at once despatched through the jungle and across the hills to Mandla, sixty miles away, for a doctor, who arrived on the fourth day after the accident.

Meanwhile, all that could be done was done, and my wounds, of which there were fourteen, were dressed. Our good Dr. Hogan had me carried into Mandla, the journey taking two and a half days, and since then, I am glad to say, I have[Pg 60] been making a wonderful recovery. It is a great mercy that my arm had not to be amputated, as I feared at first I should certainly lose it. But though it is still much swollen, and so stiff that I can only bend it a few inches, all is progressing well.

My little dog escaped with a few scratches, having saved my life. The panther has either been eaten by the tiger, or has died of its wounds. The villagers were far too scared to follow it up after my fall. Its bones, if not devoured by tigers or porcupines, will most likely be found higher up the nala than where we last saw it.

A Panther-hunt, which had a somewhat unexpected conclusion, is narrated by the Rev. T. Fuller Bryant:—

At the outset I may explain that strictly it was not a panther that figures in this story, but that is the name—or more commonly "painter"—given to the puma, or cougar, of North America. At one time this animal was as common all the country over as the fox is in England at present, and even more so, but as the result of the increase and spread of population it is now found only in remote parts, and is becoming increasingly rare.

Thirty years ago, however, when I resided in America, and when the incident happened which I am about to relate, there were considerable numbers to be found in parts of the Alleghany Mountains, and not infrequently an odd one[Pg 61] would travel farther afield on a marauding expedition.

At the time of which I write I was residing at Brookfield, about thirty miles north of Utica. It was near the end of October, when, according to custom, all were busy banking up the sides of their houses, and in other ways preparing for winter, when complaints began to be made by the farmers of depredations among their sheep, by, as was supposed, some dog or dogs unknown. Hardly a morning came but some farmer or other found his flock reduced in this way, until the whole neighbourhood was roused to excited indignation against the whole dog tribe. Suspicion fell in turn upon almost every poor cur of the neighbourhood, and many a poor canine innocent was done to death, some by drowning, others by poison, and more by shooting; until it seemed as if all the sheep and dogs of the countryside would be wiped out.

What served only to deepen the mystery was the fact that here and there a calf was killed and partly eaten, indicating that if it were the work of a dog it must be one of unusual size, strength, and ferocity. So exasperated did the farmers become at length, that a meeting was held at Brookfield, at which it was resolved to offer a reward of two hundred dollars, "to any one killing the dog, or other animal, or giving such information as would lead to its discovery." The words "or other animal" had been inserted at the suggestion of a man who had heard unusual noises[Pg 62] at night proceeding from the Oneida Swamp, a desolate, densely wooded tract of country, extending to within a mile or so of his dwelling. This circumstance had created in his mind the suspicion that the cause of all the trouble might not, after all, be a dog, but this he kept to himself.

One morning my brother and I, with three others, started early for a day's shooting and hunting in some woods three or four miles north of the village; but having an engagement at home in the afternoon, I left the party soon after one o'clock. When within about two miles of the village I left the main road to take a short cut across the land of a man named John Vidler, an Englishman.