« back

[Transcriber's Note: At least four variations of the title of the book are present in the text. For details, see the Transcriber's Note at the end of the text.]

|

Campfire Girls at Twin Lakes OR, The Quest of a Summer Vacation BY STELLA M. FRANCIS M. A. DONOHUE & CO. CHICAGO NEW YORK |

CAMPFIRE GIRLS’ SERIES

Campfire Girls in the Alleghany Mountains; or, A Christmas Success Against Odds.

Campfire Girls in the Country; or, The Secret Aunt Hannah Forgot.

Campfire Girls’ Trip Up the River; or, Ethel Hollister’s First Lesson.

Campfire Girls’ Outing; or, Ethel Hollister’s Second Summer in Camp.

Campfire Girls’ on a hike; or, Lost in the Great North Woods.

Campfire Girls at Twin Lakes; or, The Quest of a Summer Vacation.

COPYRIGHT

1918

M. A. Donohue & Company

MADE IN U. S. A.

Index

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | ABOUT TEETH AND TEDDY BEARS. | 9 |

| II. | A SPECIAL MEETING CALLED. | 13 |

| III. | A BOY AND A FORTUNE. | 18 |

| IV. | THE GIRLS VOTE “AYE.” | 23 |

| V. | HONORS AND SPIES. | 27 |

| VI. | A TELEGRAM EN ROUTE. | 32 |

| VII. | A DOUBLE-ROOM MYSTERY. | 36 |

| VIII. | PLANNING IN SECRET. | 42 |

| IX. | FURTHER PLANS. | 47 |

| X. | A TRIP TO STONY POINT. | 51 |

| XI. | MISS PERFUME INTERFERES. | 56 |

| XII. | THE MAN IN THE AUTO. | 61 |

| XIII. | A NONSENSE PLOT. | 65 |

| XIV. | SPARRING FOR A FEE. | 70 |

| XV. | LANGFORD GETS A CHECK. | 75 |

| XVI. | LANGFORD CHECKS UP. | 82 |

| XVII. | A DAY OF HARD WORK. | 87 |

| XVIII. | PLANNING. | 91 |

| XIX. | WATCHED. | 95 |

| XX. | THE MISSILE. | 100 |

| XXI. | “SH!” | 104 |

| XXII. | THE GRAHAM GIRLS CALL. | 108 |

| XXIII. | “HIGH C.” | 115 |

| XXIV. | THE RUNAWAY. | 120 |

| XXV. | A LITTLE SCRAPPER. | 125 |

| XXVI. | AMMUNITION AND CATAPULTS. | 130 |

| XXVII. | THE GHOST. | 136 |

| XXVIII. | A BUMP ON THE HEAD. | 141 |

| XXIX. | A CRUEL WOMAN. | 146 |

| XXX. | THE GIRLS WIN. | 151 |

CAMP FIRE GIRLS AT TWIN LAKES

OR

The Quest of a Summer Vacation

BY STELLA M. FRANCIS

CHAPTER I.

ABOUT TEETH AND TEDDY BEARS.

“Girls, I have some great news for you. I’m sure you’ll be interested, and I hope you’ll be as delighted as I am. Come on, all of you. Gather around in a circle just as if we were going to have a Council Fire and I’ll tell you something that will—that will—Teddy Bear your teeth.”

A chorus of laughter, just a little derisive, greeted Katherine Crane’s enigmatical figure of speech. The merriment came from eleven members of Flamingo Camp Fire, who proceeded to form an arc of a circle in front of the speaker on the hillside grass plot near the white canvas tents of the girls’ camp.

“What does it mean to Teddy Bear your teeth?” inquired Julietta Hyde with mock impatience. “Come, Katherine, you are as much of a problem with your ideas as Harriet Newcomb is with her big words. Do you know the nicknames some of us are thinking of giving to her?”10

“No, what is it?” Katherine asked.

“Polly.”

“Polly? Why Polly?” was the next question of the user of obscure figures of speech, who seemed by this time to have forgotten the subject that she started to introduce when she opened the conversation.

“Polly Syllable, of course,” Julietta answered, and the burst of laughter that followed would have been enough to silence the most ambitious joker, but this girl fun-maker was not in the least ambitious, so she laughed appreciatively with the others.

“Well, anyway,” she declared after the merriment had subsided; “Harriet always uses her polysyllables correctly, so I am not in the least offended at your comparison of my obscurities with her profundities. There, how’s that? Don’t you think you’d better call me Polly, too?”

“Not till you explain to us what it means to Teddy Bear one’s teeth,” Azalia Atwood stipulated sternly. “What I’m afraid of is that you’re trying to introduce politics into this club, and we won’t stand for that a minute.”

“Oh, yes, Julietta, you may have your wish, if what Azalia says is true,” Marie Crismore announced so eagerly that everybody present knew that she had an idea and waited expectantly for it to come out. “We’ll call you Polly—Polly Tix.”

Of course everybody laughed at this, and11 then Harriet Newcomb demanded, that her rival for enigmatical honors make good.

“What does it mean to Teddy Bear one’s teeth?” she demanded.

“Oh, you girls are making too much of that remark,” Katherine protested modestly, “I really am astonished at every one of you, ashamed of you, in fact, for failing to get me. I meant that you would be delighted—dee-light-ed—get me?—dee-light-ed.”

“Oh, I get you,” Helen Nash announced, lifting her hand over her head with an “I know, teacher,” attitude.

“Well, Helen, get up and speak your piece,” Katherine directed.

“You referred to the way Theodore Roosevelt shows his teeth when he says he’s ‘dee-light-ed’; but we got you wrong. When you said you would tell us something that would ‘Teddy Bear’ our teeth, you meant b-a-r-e, not b-e-a-r. When Teddy laughs, he bares his teeth. Isn’t that it?”

“This isn’t the first time that Helen Nash has proved herself a regular Sherlock Holmes,” Marion Stanlock declared enthusiastically. “We are pretty well equipped with brains in this camp, I want to tell you. We have Harriet, the walking dictionary; Katherine, the girl enigma; and Helen, the detective.”

“Every girl is supposed to be a puzzle,” Ernestine Johanson reminded. “I don’t like to snatch any honors away from anyone, but,12 you know, we should always have the truth.”

“Yes, let us have the truth about this interesting, Teddy-teeth-baring, dee-light-ing announcement that Katherine has to make to us,” Estelle Adler implored.

“The delay wasn’t my fault,” Katherine said, with an attitude of “perfect willingness if all this nonsense will stop.” “But here comes Miss Ladd. Let’s wait for her to join us, for I know you will all want her opinion of the proposition I am going to put to you.”

Miss Harriet Ladd, Guardian of the Fire, bearing a large bouquet of wild flowers that she had just gathered in timber and along the bank of the stream, joined the group of girls seated on the grass a minute later, and then all waited expectantly for Katherine to begin.

CHAPTER II.

A SPECIAL MEETING CALLED.

Fern hollow—begging the indulgence of those who have read the earlier volume of this series—is a deep, richly vegetated ravine or gully forming one of a series of scenic convolutions of the surface of the earth which gave the neighboring town of Fairberry a wide reputation as a place of beauty.

The thirteen Camp Fire Girls, who had pitched their tents on the lower hillside, a few hundred feet from a boisterous, gravel-and-boulder bedded stream known as Butter creek, were students at Hiawatha Institute, a girls’ school in a neighboring state. The students of that school were all Camp Fire Girls, and it was not an uncommon thing for individual Fires to spend parts of their vacations together at favorite camping places. On the present occasion the members of Flamingo Fire were guests of one of their own number, Hazel Edwards, on the farm of the latter’s aunt, Mrs. Hannah Hutchins, which included a considerable section of the scenic Ravine known as Fern hollow.

They had had some startling adventures in the last few weeks, and although several days had elapsed since the windup in these events and it seemed that a season of quiet, peaceful camp life was in store for them, still they were14 sufficiently keyed up to the unusual in life to accept surprises and astonishing climaxes as almost matters of course.

But all of these experiences had not rendered them restless and discontented when events slowed down to the ordinary course of every-day life, including three meals a day, eight hours’ sleep, and a program of tramps, exercises and honor endeavors. The girls were really glad to return to their schedule and their handbook for instructions as to how they should occupy their time. After all, adventures make entertaining reading, but very few, if any, persons normally constituted would choose a melodramatic career if offered as an alternative along with an even-tenor existence.

All within one week, these girls had witnessed the execution of an astonishing plot by a band of skilled lawbreakers and subsequently had followed Mrs. Hutchins through a series of experiences relative to the loss of a large amount of property, which she held in trust for a relative of her late husband, and its recovery through the brilliant and energetic endeavors of some of the members of the Camp Fire, particularly Hazel Edwards and Harriet Newcomb. The chief culprit, Percy Teich, a nephew of Mrs. Hutchins’ late husband, had been captured, had escaped, had been captured again and lodged in jail, and clews as to the identity of a number of the rest had been worked out by the police, so15 that the hope was expressed confidently that eventually they, too, would be caught.

“Mrs. Hutchins is very grateful for the part this Camp Fire took in the recovery of the lost securities of which she was trustee,” Katherine announced by way of introducing her “great news” to the members of the Fire who assembled in response to her call. “Of course Hazel did the really big things, assisted and encouraged by the companionship of Harriet and Violet, but Mrs. Hutchins feels like thanking us all for being here and looking pleasant.”

Hazel Edwards, niece of Mrs. Hutchins, was not present during this conversation. By prearranged purpose, she was absent from the camp when Katherine put to the other girls the proposition made by the wealthy aunt of their girl hostess. The reason it was decided best for her to remain away while the other girls were considering the plan was that it was feared that her presence might tend to suppress arguments against its acceptance, and that was a possibility which Hazel and her aunt wished to avoid. So Katherine was selected to lay the matter before the Camp Fire because she was no more chummy with Hazel than any of the other girls.

“Let’s make this a special business meeting,” suggested Miss Ladd, who had already discussed the proposition with Katherine and Mrs. Hutchins. “What Katherine has to say interests you as an organization. You’d have16 to bring the matter up at a business meeting anyway to take action on it and our regular one is two weeks ahead. We can’t wait that long if we are going to do anything on the subject.”

It was a little after 10 o’clock and the girls had been working for the last hour at various occupations which appeared on their several routine schedules for this part of the day. In fact, all of their regular academic and handwork study hours were in the morning. Just before Katherine called the girls together, they were seated here and there in shaded spots on camp chairs or on the grass in the vicinity of the camp, occupied thus:

Violet Munday and Marie Crismore were studying the lives of well-known Indians. Julietta Hyde and Estelle Adler were reading a book of Indian legends and making a study of Indian symbols. Harriet Newcomb and Azalia Atwood were studying the Camp Fire hand-sign language. Ernestine Johanson and Ethel Zimmerman were crocheting some luncheon sets. Ruth Hazelton and Helen Nash were mending their ceremonial gowns. Marion Stanlock was making a beaded head band and Katherine Crane, secretary of the Fire, was looking over the minutes of the last meeting and preparing a new book in which to enter the records of the next meeting.

Everybody signifying assent to the Guardian’s suggestion, a meeting was declared and called to order, the Wohelo Song was sung,17 the roll was called, the minutes of the last meeting were read, the reports of the treasurer and committees were deferred, as were also the recording of honors in the Record Book and the decorating of the count, and then the Guardian called for new business. This was the occasion for Katherine to address the meeting formally on the matter she had in mind.

CHAPTER III.

A BOY AND A FORTUNE.

“Now,” said Katherine after all the preliminaries of a business meeting had been gone through, “I’ll begin all over again, so that this whole proceeding may be thoroughly regular. I admit I went at it rather spasmodically, but you know we girls are constituted along sentimental lines, and that is one of the handicaps we are up against in our efforts to develop strong-willed characters like those of men.”

“I don’t agree with you,” Marie Crismore put in with a rather saucy pout. “I don’t believe we are built along sentimental lines at all. I’ve known lots of men—boys—a few, I mean—and have heard of many more who were just as sentimental as the most sentimental girl.”

There were several half-suppressed titters in the semicircle of Camp Fire Girls before whom Katherine stood as she began her address. Marie was an unusually pretty girl, a fact which of itself was quite enough to arouse the humor of laughing eyes when she commented on the sentimentality of the opposite sex. Moreover, her evident confusion as she tangled herself up, in her efforts to avoid personal embarrassment, was exceedingly amusing.

“I would suggest, Katherine,” Miss Ladd interposed,19 “that you be careful to make your statement simple and direct and not say anything that is likely to start an argument. If you will do that we shall be able to get through much more rapidly and more satisfactorily.”

Katherine accepted this as good advice and continued along the lines suggested.

“Well, the main facts are these,” she said: “Mrs. Hutchins has learned that the child whose property she holds in trust is not being cared for and treated as one would expect a young heir to be treated, and something like $3,000 a year is being paid to the people who have him in charge for his support and education. The people who have him in charge get this money in monthly installments and make no report to anybody as to the welfare of their ward.

“The name of this young heir is Glen Irving. He is a son of Mrs. Hutchins’ late husband’s nephew. When Glen’s father died he left most of his property in trust for the boy and made Mr. Hutchins trustee, and when Mr. Hutchins died, the trusteeship passed on to Mrs. Hutchins under the terms of the will.

“That, you girls know, is the property which was lost for a year and a half following Mr. Hutchins’ death because he had hidden the securities where they could not be found. Although Hazel, no doubt assisted very much by Harriet, is really the one who discovered those securities and returned them20 to her aunt, still Mrs. Hutchins seems disposed to give us all some of the credit.

“For several months reports have reached Mrs. Hutchins that her grandnephew has not been receiving the best of care from the relatives who have charge of him. She has tried in various ways to find out how much truth there was in these reports, but was unsuccessful. Little Glen, who is only 10 years old, has been in the charge of an uncle and aunt on his mother’s side ever since he became an orphan three or four years ago. His father, in his will, named this uncle and aunt as Glen’s caretakers, but privately executed another instrument in which he gave Mr. and Mrs. Hutchins guardianship powers to supervise the welfare of little Glen. It was understood that these powers were not to be exercised unless special conditions made it necessary for them to step in and take charge of the boy.

“Mrs. Hutchins wants to find out now whether such conditions exist. At the time of the death of Glen’s father, he lived in Baltimore, and his uncle and aunt, who took charge of him, lived there, too. It seems that they were only moderately well-to-do and the $3,000 a year they got for the care and education of the boy was a boon to them. Of course, $3,000 a year was more than was needed, but that was the provision made by his father in his will, and as long as they had possession of the boy they were entitled to the21 money. Moreover, Mrs. Hutching understands that Glen’s father desired to pay the caretakers of his child so well that there could be no doubt that he would get the best of everything he needed, particularly education.

“But apparently his father made a big mistake in selecting the persons who were to take the places of father and mother to the little boy. If reports are true, they have been using most of the money on themselves and their own children and Glen has received but indifferent clothes, care, and education. Now I am coming to the main point of my statement to you.

“Mrs. Hutchins talked the matter over with Miss Ladd and me and asked us to put it up to you in this way: She was wondering if we wouldn’t like to make a trip to the place where Glen is living and find out how he is treated. Mrs. Hutchins has an idea that we are a pretty clever set of girls and there is no use of trying to argue her out of it. So that much must be agreed to so far as she is concerned. She wants to pay all of our expenses and has worked out quite an elaborate plan; or rather she and her lawyer worked it out together. Really, it is very interesting.”

“Why, she wants us to be real detectives,” exclaimed Violet Munday excitedly.

“No, don’t put it that way,” Julietta Hyde objected. “Just say she wants us to take the parts of fourteen Lady Sherlock Holmeses in a Juvenile drama in real life.”22

“Very cleverly expressed,” Miss Ladd remarked admiringly. “Detective is entirely too coarse a term to apply to any of my Camp Fire Girls and I won’t stand for it.”

“We might call ourselves special agents, operatives, secret emissaries, or mystery probers,” Harriet Newcomb suggested.

“Yes, we could expect something like that from our walking dictionary,” said Ernestine Johanson. “But whatever we call ourselves, I am ready to vote aye. Come on with your—or Mrs. Hutchins and her lawyers’—plan, Katherine. I’m impatient to hear the rest of it.”

Katherine produced an envelope from her middy-blouse pocket and drew from it a folded paper, which she unfolded and spread out before her.

CHAPTER IV.

THE GIRLS VOTE “AYE.”

“Before I take up the plan outlined by Mrs. Hutchins and her lawyer,” Katherine continued, as she unfolded the paper, “I want to explain one circumstance that might be confusing if left unexplained. As I said, the uncle and aunt who have Glen in charge live in Baltimore. They do not own any real estate, but rent a rather expensive apartment, which they never could support on the family income aside from the monthly payments received from Mrs. Hutchins as trustee of Glen’s estate. This family’s name is Graham, and its head, James Graham, is a bookkeeper receiving a salary of about $1,800 a year. In these war times, when the cost of living is so high, that is a very moderate salary on which to support a family of six: father, mother, two girls and two boys, including Glen.

“But this family, according to reports that have reached Mrs. Hutchins, is living in clover. Mr. Graham, who is a hard working man, still holds his bookkeeping position, but in this instance it is a case of ‘everybody loafs but father.’ He is said to be a very much henpecked husband. Mrs. Graham is said to be the financial dictator of the family.

“Now, Mrs. Graham seems to be a woman of much social ambition. Among the necessaries of the best social equipment, you know,24 is a summer cottage in a society summer resort with sufficient means to support it respectably and leisure in the summer to spend at the resort. It is said that the Grahams have all this. They have purchased or leased a cottage at Twin Lakes, which you know is only about a hundred miles from Hiawatha Institute. I think that every one of us has been there at one time or another. It is about three hundred miles from here.

“What Mrs. Hutchins wants us to do is to make a trip to Twin Lakes, pitch our tents and start a Camp Fire program just as if we were there to put in a season of recreation and honor work. But meanwhile, she wants us to become acquainted with the Graham family, cultivate an intimacy with them, if you please, and be able to report back to her just what conditions we find in their family circle, just how Glen is treated, and whether or not he gets reasonable benefits from the money given to the Grahams for his support and education.

“I have given you in detail, I think, what is outlined on this paper I hold in my hand. I don’t think I have left out anything except the names of the children of the Graham family. But there are no names at all on this paper. The reason for this is that it was thought best not to disclose the identity of the family for the information of any other person into whose hands it might fall, if it should be lost by us. The names are indicated thus: ‘A’25 stands for the oldest member of the family, Mrs. Graham, for she is two years older than her husband and the real head of the household; ‘B’ stands for the next younger, Mr. Graham; ‘C’ stands for Addie, the oldest daughter; ‘D’ for the next daughter, Olga; ‘E’ for the only son, James, named after his father; and ‘F’ stands for Glen. There, you have the whole proposition. What do you want to do with it? Mrs. Hutchins, I neglected to mention, wants to pay all of our expenses and hire help to take off our hands all the labor of moving our camp.”

Replies were not slow coming. Nearly every one of the girls had something to say, as indicated by the eager attitudes of all and requests from several to be recognized by the Guardian, who was “in the chair.” Azalia Atwood was the first one called upon.

“I think the proposition of Mrs. Hutchins is simply great,” the latter declared with vim. “It’s delightfully romantic, sounds like a story with a plot, and would make fourteen heroines out of us if we were successful in our mission.”

“I want to warn you against one danger,” Miss Ladd interposed at this point. “The natural thing for you to do at the start, after hearing this lengthy indictment of the Graham family, is to conclude that they are a bad lot and to feel an eagerness to set out to prove it. Now, I admit that that is my feeling in this matter, but I know also that there is a26 possibility of mistake. The Grahams may be high class people, but they may have enemies who are trying to injure them. If you take up the proposition of Mrs. Hutchins, you must keep this possibility in mind, for unless you do, you might do not only the Grahams a great injustice, but little Glen as well. It would be a pity to tear him away from a perfectly good home that has been vilified by false accusations made by unscrupulous enemies.”

The discussion was continued for nearly an hour, the written instructions in Katherine’s possession were read aloud and then a vote was taken. It was unanimous, in favor of performing the task proposed by Mrs. Hutchins.

CHAPTER V.

HONORS AND SPIES.

“Why couldn’t this expedition be arranged so that we girls could all win some honors out of it?” Ruth Hazelton inquired, after the details of Mrs. Hutchins’ plan had been discussed thoroughly and the vote had been taken.

“That is a good suggestion,” said Miss Ladd. “What kind of honors would you propose, Ruth?”

The latter was silent for some minutes. She was going over in her mind the list of home-craft, health-craft, camp-craft, hand-craft, nature-lore, business and patriotism honors provided for by the organization, but none of them seemed to fit in with the program of the proposed secret investigation.

“I don’t think of any,” she said at last. “There aren’t any, are there?”

“No, there are not,” the Guardian replied. “But now is the time for the exercise of a little ingenuity. Who speaks first with an idea?”

“I have one,” announced Ethel Zimmerman eagerly.

“Well, what is it, Ethel?” Miss Ladd inquired.

“Local honors,” replied the girl with the first idea. “Each Camp Fire is authorized to create local honors and award special beads28 and other emblems to those who make the requirements.”

“Under what circumstances is such a proceeding authorized?” was Miss Ladd’s next question.

“When it is found that local conditions call for the awarding of honors not provided for in the elective list.”

“Do such honors count for anything in the qualifications for higher rank?”

“They do not,” Ethel answered like a pupil who had learned her lesson very well and felt no hesitancy in making her recitation.

“What kind of honor would you confer on me if I exhibited great skill in spying on someone else?” asked Helen Nash in her usual cool and deliberate manner.

A problematical smile lit up the faces of several of the girls who caught the significance of this suggestion. Miss Ladd smiled, too, but not so problematically.

“You mean to point out the incongruity of honors and spies, I presume,” the Guardian interpreted, addressing Helen.

“Not very seriously,” the latter replied with an expression of dry humor. “I couldn’t resist the temptation to ask the question and, moreover, it occurred to me that a little discussion on the subject of honors and spies might help to complete our study of the problem before us.”

“Do you mean that we are going to be spies?” Violet Munday questioned.29

“Why, of course we are,” Helen replied, with a half-twinkle in her eyes.

“I don’t like the idea of spying on anybody and would rather call it something else,” said Marie Crismore. “First someone calls us detectives and then somebody calls us spies. What next? Ugh!”

“Why don’t you like to spy on anybody?” asked Harriet Newcomb.

“Well,” Marie answered hesitatingly; “you know that there are thousands of foreign spies in this country trying to help our enemies in Europe, and I don’t like to be classed with them.”

“That’s patriotic,” said Helen, the twinkle in her eyes becoming brighter. “But you must remember that there are spies and spies, good spies and bad spies. All of our law-enforcement officials are spies in their attempts to crush crime. Your mother was a spy when she watched you as a little tot stealing into the pantry to poke your fist into the jam. That is what Mrs. Hutchins suspects is taking place now. Someone has got his or her fist in the jam. We must go and peek in through the pantry door.”

“Oh, if you put it that way, it’ll be lots of fun,” Marie exclaimed eagerly. “I’d just like to catch ’em with their fists all—all—smeared!”

She brought the last word out so ecstatically that everybody laughed.

“I’m afraid you have fallen into the pit that I30 warned you against,” Miss Ladd said, addressing Marie. “You mustn’t start out eager to prove the persons, under suspicion, guilty.”

“Then we must drive out of our minds the picture of the fists smeared with jam,” deplored Marie with a playful pout.

“I fear that you must,” was the smiling concurrence of the Guardian.

“Very well; I’m a good soldier,” said Marie, straightening up as if ready to “shoulder arms.” “I won’t imagine any jam until I see it.”

“Here comes Hazel,” cried Julietta, and everybody looked in the direction indicated.

Hazel Edwards had taken advantage of this occasion to go to her aunt’s house and thence to the city Red Cross headquarters for a new supply of yarn for their army and navy knitting. As she emerged from the timber and continued along the edge of the woods toward the site of the camp, the assembled campers could see that she carried a good-sized bundle under one arm.

“She’s got some more yarn, and we can now take up our knitting again,” said Ethel Zimmerman, who had proved herself to be the most rapid of all the members of the Camp Fire with the needles.

Although the business of the meeting was finished, by tacit agreement those present decided not to adjourn until Hazel arrived and received official notice of what had been done.

“I’m delighted with your decision,” Hazel31 said eagerly. “And, do you know, I believe we are going to have some adventure. I’ve been talking the matter over with Aunt Hannah and she has told me a lot of very interesting things. But when do you want to go?”

“We haven’t discussed that yet,” Miss Ladd replied. “I suppose we could go almost any time.”

“Let’s go at once,” proposed Marion Stanlock. “We haven’t anything to keep us here and we can come back as soon as—as soon as we find the jam on somebody’s fist.”

This figure of speech called for an explanation for Hazel’s benefit. Then Ruth Hazelton moved that the Camp Fire place itself at Mrs. Hutchins’ service to leave for Twin Lakes as soon as she thought best, and this motion was carried unanimously.

“I move that Katherine Crane be appointed a committee of one to notify Mrs. Hutchins of our action and get instructions from her for our next move,” said Violet Munday.

“Second the motion,” said Azalia Atwood.

“Question!” shouted Harriet Newcomb.

“Those in favor say aye,” said Miss Ladd.

A hearty chorus of “ayes” was the response.

“Contrary minded, no.”

Silence.

“The ayes have it.”

The meeting adjourned.

CHAPTER VI.

A TELEGRAM EN ROUTE.

At 9 o’clock in the morning two days later, a train of three coaches, two sleepers and a parlor car, pulled out of Fairberry northwest bound. It was a clear midsummer day, not oppressively warm. The atmosphere had been freshened by a generous shower of rain a few hours before sunup.

In the parlor car near one end sat a group of thirteen girls and one young woman. The latter, Miss Ladd, Guardian of Flamingo Camp Fire, we will hereafter designate as “one of the girls.” She was indeed scarcely more than a girl, having passed her voting majority by less than a year.

The last two days had been devoted principally to preparations for this trip. Mrs. Hutchins had engaged two men who struck the tents and packed these and all the other camp paraphernalia and expressed the entire outfit to Twin Lakes station. On the morning before us, Mrs. Hutchins accompanied the fourteen girls to the train at the Fairberry depot and bade them good-bye and wished them success in their enterprise.

There were few other passengers in the parlor car when the Camp Fire Girls entered. One old gentleman obligingly moved forward from a seat at the rear end, and the new passengers33 were able to occupy a section all by themselves.

Before starting for the train, Miss Ladd called her little flock of “spies” together and gave them a short lecture.

“Now, girls,” she said with keen deliberation, “we are about to embark on a venture that has in it elements which will put many of your qualities to severe test. And these tests are going to begin right away. Perhaps the first will be a test of your ability to hold your tongues. That’s pretty hard for a bevy of girls who like to talk better than anything else, isn’t it?”

“Do you really mean to accuse us of liking to talk better than anything else?” inquired Marie Crismore, flushing prettily.

“I didn’t say so, did I?” was the Guardian’s answering query.

“Not exactly. But you meant it, didn’t you?”

“I refuse to be pinned down to an answer,” replied Miss Ladd, smiling enigmatically. “I suspect that if I leave you something to guess about on that subject it may sink in deeper. Now, can any of you surmise what specifically I am driving at?”

Nobody ventured an answer, and Miss Ladd continued:

“Don’t talk about our mission to Twin Lakes except on secret occasions. Don’t drop remarks now and then or here and there that may be overheard and make someone listen34 for more. For instance, on the train, forget that you are on anything except a mere pleasure trip or Camp Fire excursion. Be absolutely certain that you don’t drop any remarks that might arouse anybody’s curiosity or suspicion. It might, you know, get to the very people whom we wish to keep in ignorance concerning our moves and motives.”

“I see you are bound to make sure enough spies out of us,” said Marie Crismore pertly. “Well, I’m going to start out with the determination of pulling my hat down over my eyes, hiding in every shadow I see and peeking around every corner I can get to. Oh, I’m going to be some sleuth, believe me.”

“What will you say when you catch somebody with jam on his fingers?” Harriet Newcomb inquired.

Marie leaned forward eagerly and answered dramatically:

“I’ll suddenly appear before the villain and shout: ‘Halt, you are my prisoner! Throw up your jammed hands!’”

After the laugh that greeted this response subsided, Miss Ladd closed her lecture thus:

“I think you all appreciate the importance now of keeping your thoughts to yourselves except when we are in conference. I’m glad to see you have a lot of fun over this subject, but don’t let your happy spirits cause you to permit any unguarded remarks to escape.”

On the train the girls all got out their knitting, and soon their needles were plying merrily35 away on sleeveless sweaters, socks, helmets, and wristlets for the boys at the front, timing their work by their wrist watches for patriotism honors. True to their resolve, following Miss Ladd’s warning lecture, they kept the subject of their mission out of their conversation, and it is probable that no reference to it would have been made during the entire 300-mile journey if something had not happened which forced it keenly to the attention of every one of them.

The train on which they were traveling was a limited and the first stop was fifty miles from Fairberry. A few moments after the train stopped, a telegraph messenger walked into the front entrance of the parlor car and called out:

“Telegram for Miss Harriet Ladd.”

The latter arose and received the message, signed the receipt blank, and tore open the envelope. Imagine her astonishment as she read the following:

“Miss Harriet Ladd, parlor car, Pocahontas Limited: Attorney Pierce Langford is on your train, first coach. Bought ticket for Twin Lakes. Small man, squint eyes, smooth face. Watch out for him. Letter follows telegram. Mrs. Hannah Hutchins.”

CHAPTER VII.

A DOUBLE-ROOM MYSTERY.

Miss Ladd passed the telegram around among the girls after writing the following explanation at the foot of the message:

“Pierce Langford is the Fairberry attorney that represented scheming relatives of Mrs. Hutchins’ late husband, who attempted to force money out of her after the disappearance of the securities belonging to Glen Irving’s estate. Leave this matter to me and don’t talk about it until we reach Twin Lakes.”

Nothing further was said about the incident during the rest of the journey, as requested by Miss Ladd. The girls knitted, rested, chatted, read, and wrote a few postcards or “train letters” to friends. But although there was not a word of conversation among the Camp Fire members relative to the passenger named in Mrs. Hutchins’ telegram, yet the subject was not absent from their minds much of the time.

They were being followed! No other construction could be put upon the telegram. But for what purpose? What did the unscrupulous lawyer—that was the way Mrs. Hutchins had once referred to Pierce Langford—have in mind to do? Would he make trouble for them in any way that would place them in an37 embarrassing position? These girls had had experiences in the last year which were likely to make them apprehensive of almost anything under such circumstances as these.

Warned of the presence on the train of a probable agent of the family that Mrs. Hutchins had under suspicion, the girls were constantly on the alert for some evidence of his interest in them and their movements. And they were rewarded to this extent: In the course of the journey, Langford paid the conductor the extra mileage for parlor car privileges, and as he transferred from the coach, not one of the Flamingoites failed to observe the fact that in personal appearance he answered strikingly the description of the man referred to in the telegram received by Miss Ladd.

The squint-eyed man of mystery, in the coolest and most nonchalant manner, took a seat a short distance in front of the bevy of knitting Camp Fire Girls, unfolded a newspaper and appeared to bury himself in its contents, oblivious to all else about him.

Half an hour later he arose and left the car, passing out toward the rear end of the train. Another half hour elapsed and he did not reappear. Then Katherine Crane and Hazel Edwards put away their knitting and announced that they were going back into the observation car and look over the magazines. They did not communicate to each other their real purpose in making this move, but neither38 had any doubt as to what was going on in the mind of the other. Marie Crismore looked at them with a little squint of intelligence and said as she arose from her chair:

“I think I’ll go, too, for a change.”

But this is what she interpolated to herself:

“They’re going back there to spy, and I think I’ll go and spy, too.”

They found Langford in the observation car, apparently asleep in a chair. Katherine, who entered first, declared afterwards that she was positive she saw him close his eyes like a flash and lapse into an appearance of drowsiness, but if she was not in error, his subsequent manner was a very clever simulation of midday slumber. Three or four times in the course of the next hour he shifted his position and half opened his eyes, but drooped back quickly into the most comfortable appearance of somnolent lassitude.

The three girls were certain that all this was pure “make-believe,” but they did not communicate their conviction to each other by look or suggestion of any kind. They played their part very well, and it is quite possible that Langford, peeking through his eyewinkers, was considerably puzzled by their manner. He had no reason to believe that he was known to them by name or reputation, much less by personal appearance.

It was in fact a game of spy on both sides during most of the journey, with little but39 mystifying results. The train reached Twin Lakes at about sundown, and even then the girls had discovered no positive evidence as to the “squint-eyed man’s” purpose in taking the trip they were taking. And Langford, as he left the train, could not confidently say to himself that he had detected any suggestion of interest on their part because of his presence on the train.

Flamingo Camp Fire rode in an omnibus to the principal hotel in the town, the Crandell house, and were assigned to rooms on the second floor. They had had their supper on the train and proceeded at once to prepare for a night’s rest. Still no words were exchanged among them relative to the purpose of their visit or the mysterious, squint-eyed passenger concerning whom all of them felt an irrepressible curiosity and not a little apprehension.

Miss Ladd occupied a room with Katherine Crane. After making a general survey of the floor and noting the location of the rooms of the other girls, they entered their own apartment and closed the door. Marie Crismore and Julietta Hyde occupied the room immediately south of theirs, but to none of them had the room immediately north been assigned.

“I wonder if the next room north is occupied,” Katherine remarked as she took off her hat and laid it on a shelf in the closet.

“Someone is entering now,” Miss Ladd40 whispered, lifting her hand with a warning for low-toned conversation.

The exchange of a few indistinct words between two persons could be heard; then one of them left, and the other was heard moving about in the room.

“That’s one of the hotel men who just brought a new guest up,” Katherine remarked.

“And I’m going to find out who it is,” the Guardian declared in a low tone, turning toward the door.

“I’ll go with you,” said Katherine, and together they went down to the office.

They sought the register at once and began looking over the list of arrivals. Presently Miss Ladd pointed with her finger the following registration:

“Pierce Langford, Fairberry, Room 36.”

Miss Ladd and Katherine occupied Room 35.

“Anything you wish, ladies?” asked the proprietor, who stood behind the desk.

“Yes,” Miss Ladd answered. “We want another room.”

“I’ll have to give you single rooms, if that one is not satisfactory,” was the reply. “All my double rooms are filled.”

“Isn’t 36 a double room?” Katherine inquired.

“Yes, but it’s occupied. I just sent a man up there.”

“Excuse the question,” Miss Ladd said curiously; “but41 why did you put one person in a double room when it was the only double room you had and there were vacant single rooms in the house?”

The hotel keeper smiled pleasantly, as if the question was the simplest in the world to answer.

“Because he insisted on having it and paid me double rate in advance,” was the landlord’s startling reply.

CHAPTER VIII.

PLANNING IN SECRET.

Without a word of comment relative to this remarkable information, Miss Ladd turned and started back upstairs, and Katherine followed. In the hall at the upper landing, the Guardian whispered thus in the ear of her roommate:

“Sh! Don’t say a word or commit an act that could arouse suspicion. He’s probably listening, or looking, or both. Just forget this subject and talk about the new middy-blouse you are making, or something like that. Don’t gush, either, or he may suspect your motive. We want to throw him off the track if possible.”

But Katherine preferred to say little, for she was tired, and made haste to get into bed. It was not long before the subject of their plans and problems and visions of spies and “jam-stained fists” were lost in the lethe of dreamland.

They were awakened in the morning by the first breakfast bell and arose at once. They dressed hurriedly and went at once to the dining-room, where they found two of the girls ahead of them. The others appeared presently.

As the second bell rang, Pierce Langford sauntered into the room and took a seat near43 the table occupied by Helen Nash and Violet Munday. He looked about him in a half-vacant inconsequential way and then began to “jolly” the waitress, who approached and sung off a string of alternates on the “Hooverized” bill of fare which she carried in her mind. She coldly ignored his “jollies,” for it was difficult for Langford to be pleasing even when he tried to be pleasant, took his order, and proceeded on her way.

The girls paid no further attention to the supposed spy-lawyer during breakfast, and the latter appeared to pay no further attention to them. After the meal, Miss Ladd called the girls together and suggested that they take a walk. Then she dismissed them to prepare. Twenty minutes later they reassembled, clad in khaki middy suits, brown sailor hats, and hiking shoes, and the walk was begun along a path that led down a wooded hill behind the hotel and toward the nearest lake.

It was not so much for exercise and fresh air that this “hike” was taken as for an opportunity to hold a conference where there was little likelihood of its being overheard. They picked a grassy knoll near the lake, shaded by a border of oak and butternut trees, and sat down close together in order that they might carry on a conversation in subdued tones.

“Now,” said Miss Ladd, “we’ll begin to form our plans. You all realize, I think, that we have an obstacle to work against that we did44 not reckon on when we started. But that need not surprise us. In fact, as I think matters over, it would have been surprising if something of the kind had not occurred. This man Langford is undoubtedly here to block our plans. If that is true, in a sense it is an advantage to us.”

“Why?” Hazel Edwards inquired.

“I don’t like the idea of answering questions of that kind without giving you girls an opportunity to answer them,” the Guardian returned. “Now, who can tell me why it is an advantage to us to be followed by someone in the employ of the people whom we have been sent to investigate.”

“I think I can answer it,” Hazel said quickly, observing that two or three of the other girls seemed to have something to say. “Let me speak first, please. I asked the foolish question and want a chance to redeem myself.”

“I wouldn’t call it foolish,” was the Guardian’s reassuring reply. “It was a very natural question and one that comparatively few people would be able to answer without considerable study. And yet, it is simple after you once get it. But go ahead and redeem yourself.”

“The fact that someone has been put on our trail to watch us is pretty good evidence that something wrong is going on,” said Hazel. “You warned us not to be sure that anybody is guilty until we see the jam on his fist. But we can work more confidently if we are reasonably45 certain that there is something to work for. If this man Langford is in the employ of the Grahams and is here watching us for them, we may be reasonably certain that Aunt Hannah was right in her suspicions about the way little Glen is being treated, may we not?”

“That is very good, Hazel,” Miss Ladd commented enthusiastically. “Many persons a good deal older than you could not have stated the situation as clearly as you have stated it. Yes, I think I may say that I am almost glad that we are being watched by a spy.

“But I didn’t call you out here to have a long talk with you, girls. There really isn’t much to say right now. First I wanted you all to understand clearly that we are being watched and for what purpose. Langford convicted himself when he asked for the double room next to the one occupied by Katherine and me and offered to pay the regular rate for two. He thinks that he is able to maintain an appearance of utter disinterest in us and throw us off our guard. But he overdoes the thing. He makes too big an effort to appear unconscious of our presence. It doesn’t jibe at all with the expression of decided interest I have caught on his face on two or three occasions. And I flatter myself that I successfully concealed my interest in his interest in us.

“Now, there are two things I want to say to you, and we will return. First, do your best, every one of you, to throw Langford off46 the track by affecting the most innocent disinterest in him as of no more importance to us than the most obscure tourist on earth. Don’t overdo it. Just make yourselves think that he is of no consequence and act accordingly without putting forth any effort to do so. The best way to effect this is to forget all about our mission when he is around.

“Second, we must find out where the Graham cottage is and then determine where we want to locate our camp—somewhere in the vicinity of the Graham cottage, of course.”

“Let me go out on a scouting expedition to find out where they live,” Katherine requested.

“And let me go with her,” begged Ruth Hazelton.

“All right,” Miss Ladd assented. “I’ll commission you two to act as spies to approach the border of the enemy’s country and make a map of their fortifications. But whatever you do, don’t get caught. Keep your heads, don’t do anything foolish or spasmodic, and keep this thing well in mind, that it is far better for you to come back empty handed than to make them suspicious of any ulterior motive on your part.”

CHAPTER IX.

FURTHER PLANS.

“Now, girls,” said Miss Ladd, addressing Katherine and Hazel, “let me hear what your plan is, if you have any. If you haven’t any, we must get busy and work one out, for you must not start such an enterprise without having some idea as to how you should go about it. But I will assume that a suggestion must have come to you as to how best to get the first information we want or you would not have volunteered.”

“Can’t we work out an honor plan as we decide upon our duties and how we are to perform them?” Hazel inquired.

“Certainly,” the Guardian replied, “I was going to suggest that very thing. What would you propose, Hazel?”

“Well, something like this,” the latter replied: “that each of us be assigned to some specific duty to perform in the work before it, and that we be awarded honors for performing those duties intelligently and successfully.”

“Very well. I suppose this work you and Katherine have selected may count toward the winning of a bead for each of you. But what will you do after you have finished this task, which can hardly consume more than a few hours?”48

“Why not make them a permanent squad of scouts to go out and gather advance information needed at any time before we can determine what to do?” Marion Stanlock suggested.

“That’s a good idea,” Miss Ladd replied. “But it will have to come up at a business meeting of the Camp Fire in order that honors may be awarded regularly. Meanwhile I will appoint you two girls as scouts of the Fire, and this can be confirmed at the next business meeting. We will also stipulate the condition on which honors will be awarded. But how will you go about to get the information we now need?”

“First, I would look in the general residence directory to find out where the Grahams live,” Katherine replied.

“Yes, that is perhaps the best move to make first. But the chances are you will get nothing there. Can you tell me why?”

“Because there are probably few summer cottages within the city limits,” Hazel volunteered.

“Exactly,” the Guardian agreed. “Well, if the city directory fails to give you any information, what would you do next?”

“Consult a telephone directory,” Katherine said quickly.

“Fine!” Miss Ladd exclaimed. “What then?”

“They probably have a telephone; wouldn’t be much society folks if they didn’t,” Katherine49 continued; “and there would, no doubt, be some sort of address for them in the ’phone book.”

“Yes.”

“And that would give us some sort of guide for beginning our search. We wouldn’t have to use the names of the people we are looking for.”

“That is excellent!” Miss Ladd exclaimed enthusiastically. “If you two scouts use your heads as cleverly as that all the time, you ought to get along fine in your work. But go on. What next would you do?”

“Go and find out where the people live. That needn’t be hard. Then we’d look over the lay of the land to see if there were a good place nearby for us to pitch our tents.”

“Yes,” put in Hazel; “and if we found a good place nearby, we’d begin the real work that we came here to do by going to the Graham house and asking who owns the land.”

“Fine again,” Miss Ladd said. “I couldn’t do better myself, maybe not as well. I did think of going with you on your first trip, but I guess I’ll leave it all to you. Let’s go back to the hotel now, and while you two scouts are gone scouting, the rest of us will find something to entertain us. Maybe we’ll take a motorboat ride.”

They started back at once and were soon at the hotel. Katherine and Hazel decided that they would not even look for the address of the Grahams in the directories at the hotel,50 but would go to a drug store on the main business street for this information.

The other girls waited on the hotel portico while they were away on this mission. They were gone about twenty minutes and returned with a supply of picture postcards to mail to their friends. On a piece of paper Katherine had written an address and she showed it to Miss Ladd. Here is what the latter read:

“Stony Point.”

“That’s about three miles up the lake,” Hazel said. “We thought we’d hire an automobile and go up there.”

“Do,” said Miss Ladd approvingly. “And we’ll take a motorboat and ride up that way too, if we can get one. Oh, I have the idea now. We’ll make it a double inspection, part by land and part from the lake. We’ll meet you at a landing at Stony Point, if there is one, and will bring you back in the boat. Now, you, Katherine and Hazel, wait here while I go and find a motorboatman and make arrangements with him.”

“I’ll go with you,” said Violet Munday.

The Guardian and Violet hastened down toward the main boat landing while the other twelve girls waited eagerly for a successful report on this part of the proposed program.

CHAPTER X.

A TRIP TO STONY POINT.

Miss Ladd and Violet returned in about twenty minutes and reported that satisfactory arrangements had been made for a trip up the lake. They were to start in an hour and a half.

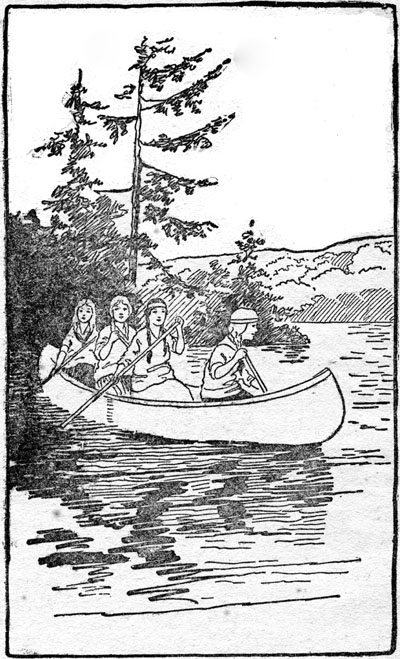

Then Katherine and Hazel engaged an automobile for a few hours’ drive and before the motorboat started with its load of passengers, they were speeding along a hard macadam road toward the point around which centered the interest of their interrupted vacation plans at Fairberry and their sudden departure on a very unusual and very romantic journey.

Twin Lakes is a summer-resort town located on the lower of two bodies of water, similar in size, configuration, and scenery. The town has a more or less fixed population of about 2,500, most of whom are retired folk of means or earn their living directly or indirectly through the supplying of amusements, comfort, and sustenance for the thousands of pleasure and recreation seekers that visit the place every year.

Each of the lakes is about four miles long and half as wide. A narrow river, strait, or rapids nearly a mile long connects the two. Originally this rapids was impassable by boats larger than canoes, and even such little craft52 were likely to be overturned unless handled by strong and skillful canoemen; but some years earlier the state had cleared this passage by removing numerous great boulders and shelves of rock from the bed of the stream so that although the water rushed along just as swiftly as ever, the passage was nevertheless safe for all boats of whatever draught that moved on the two lakes which it connected.

The lower of the twin bodies of water had been named Twin-One because, perhaps, it was the first one seen, or more often seen by those who chose or approved the name; the other was Twin-Two. Geographically speaking, it may be, these names should have been applied vice versa, for Twin-Two was fed first by a deep and wide river whose source was in the mountains 200 miles away, and Twin-One received these waters after they had laved the shores of Twin-Two.

The road followed by Katherine and Hazel in their automobile drive to Stony Point was a well-kept thoroughfare running from the south end of Twin-One, in gracefully curved windings along the east border of the lake, sometimes over a small stretch of rough or hilly shoreland, but usually through heavy growths of hemlock, white pine, oak, and other trees more or less characteristic of the country. Here and there along the way was a cottage, or summer house of more pretentious proportions, usually constructed near the water or some distance up on the side of53 the hill-shore, with a kind of terrace-walk leading down to a boat landing.

The trip was quickly made. Stony Point the girls found to be a picturesque spot not at all devoid of the verdant beauties of nature in spite of the fact that, geographically, it was well named. This name was due principally to a rock-formed promontory, jutting out into the lake at this point and seeming to be bedded deep into the lofty shore-elevation. Right here was a cluster of cottages, not at all huddled together, but none the less a cluster if viewed from a distance upon the lake, and in this group of summer residences appeared to be almost sufficient excuse for the drawing up of a petition for incorporation as a village. But very few of the owners of these houses lived in them during the winter months. The main and centrally located group consisted of a hotel and a dozen or more cottages, known as “The Hemlocks”, and so advertised in the outing and vacation columns of newspapers of various cities.

On arriving at “the Point,” Katherine and Hazel paid the chauffeur and informed him they would not need his machine any more that day. Then they began to look about them.

They were rather disappointed and decidedly puzzled at what they saw. Evidently they had a considerable search before them to discover the location of the Graham cottage without making open inquiry as to where it54 stood. First they walked out upon the promontory, which had a flat table-like surface and was well suited for the arousing of the curiosity of tourists. There they had a good view up and down the bluff-jagged, hilly and tree-laden coast.

“It’s 11 o’clock now,” said Hazel, looking at her wrist-watch. “The motorboat will be here at about 1 o’clock, and we have two hours in which to get the information we are after unless we want to share honors for success with the other girls when they arrive.”

“Let’s take a walk through this place and see what we can see,” Katherine suggested. “The road we came along runs through it and undoubtedly there are numerous paths.”

This seemed to be the best thing to do, and the two girls started from the Point toward the macadam highway. The latter was soon reached and they continued along this road northward from the place where they dismissed the automobile. Half a mile they traveled in this direction, their course keeping well along the lake shore. They passed several cottages of designedly rustic appearance and buried, as it were, amid a wealth of tree foliage and wild entanglements of shrubbery. Suddenly Katherine caught hold of Hazel’s arm and held her back.

“Did you hear that?” she inquired.

“Yes, I did,” Hazel replied. “It sounded like a child’s voice, crying.”55

“And not very far away, either. Listen; there it is again.”

It was a half-smothered sob that reached their ears and seemed to come from a clump of bushes to the left of the road not more than a dozen yards away. Both girls started for the spot, circling around the bushes and peering carefully, cautiously ahead of them as they advanced. The subdued sobs continued and led the girls directly to the spot whence they came.

Presently they found themselves standing over the form of a little boy, his frightened, tear-stained face turned up toward them while he shrank back into the bushes as if fearing the approach of a fellow human being.

CHAPTER XI.

MISS PERFUME INTERFERES.

The little fellow retreated into the bushes as far as he could get and crouched, there in manifest terror. Katherine and Hazel spoke gently, sympathetically to him, but with no result, at first, except to frighten him still more, if possible.

“Don’t be afraid, little boy,” Hazel said, reaching out her hands toward him. “We won’t hurt you.”

But he only shrank back farther, putting up his hands before his face and crying, “Don’t, don’t!”

“What can be the matter with him?” said Hazel. “He doesn’t seem to be demented. He’s really afraid of something.”

Katherine looked all around carefully through the trees and into the neighboring bushes.

“I can’t imagine what it can be,” she replied. “There’s nothing in sight that could do him any harm. But, do you know, Hazel, I have an idea that may be worth considering. Suppose this should prove to be the little boy for whom we are looking.”

“That could hardly be,” Hazel answered dubiously. “Look at his threadbare clothes, and how unkempt and neglected he appears to be. He surely doesn’t look like a boy for whose care $250 is paid every month.”57

“Don’t forget what it was that sent us here,” Katherine reminded. “Isn’t it just possible that this little boy’s fright is proof of the very condition we came here to expose?”

“Yes, it’s possible,” Hazel replied thoughtfully. “At least, we ought not neglect to find out what this means.”

Then turning again to the crouching figure in the bushes, she said:

“What is your name, little boy? Is it Glen?”

At the utterance of this name, the youth shook as with ague.

“Look out, Hazel; he’ll have a spasm,” Katherine cautioned. “He thinks we are not his friends and are going to do something he doesn’t want us to do. Let me talk to him:

“Listen, little boy,” she continued, addressing the pitiful crouching figure. “We’re not going to hurt you. We’ll do just what you want us to do. We’ll take you where you want to go. Will that be all right?”

A relaxing of the tense attitude of the boy indicated that he was somewhat reassured by these words. His fists went suddenly to his eyes and he began to sob hysterically. Hazel moved toward him with more sympathetic reassurance, when there was an interruption of proceedings from a new source.

A girl about 18 years old stepped up in front of the two Camp Fire Girls and reached forward as if to seize the juvenile refugee with both hands. She was rather ultra-stylishly58 clad for a negligee, summer-resort community, wearing a pleated taffeta skirt and Georgette crepe waist and a white sailor hat of expensive straw with a bright blue ribbon around the crown. Hazel afterwards remarked that “her face was as cold as an iceberg and the odor of perfume about her was enough to asphyxiate a field of phlox and shooting-stars.”

The boy ceased sobbing as he beheld this new arrival and his face became white with fear, while he shrank back again into the bushes as far as he could get. The girl of much perfume and stylish attire seemed to be unmoved by the new panic that seized him, but took hold of him and dragged him roughly out of his hiding place.

“Oh, do be careful,” pleaded Hazel. “Don’t you see he’s scared nearly to death? You may throw him into a spasm.”

“Is that any of your business?” the captor of the frightened youth snapped, looking defiantly at the one who addressed her. “He’s my brother, and I guess I can take him back home without any interference from a perfect stranger. He’s run away.”

“I beg your pardon,” Hazel said gently; “but it didn’t seem to me to be an ordinary case of fright. I didn’t mean to intrude, but he’s such a dear little boy I couldn’t help being sympathetic.”

“He’s a naughty bad runaway and ought to be whipped,” the girl with the cold face returned59 as she started along a path through the timber, dragging the little fellow after her.

“Isn’t that a shame!” Hazel muttered, digging her fingernails into the palms of her hands. “My, but I just like to——”

She stopped for want of words to express her feelings not too riotously, and Katherine came to her relief by swinging the subject along a different track.

“Do you really believe that boy is Glen Irving?” she inquired.

“No, I suppose not,” Hazel answered dejectedly. “You heard that girl say he was her brother, didn’t you? Well, Glen has no sister. But, do you know, I really am disappointed to find that he isn’t the boy we are looking for, for my heart went right out to him when I first saw his crouching form and white face. Moreover, I can hardly bear the thought of leaving him in the hands of that frosted bottle of cheap Cologne.”

Katherine laughed at the figure.

“You’ve painted her picture right,” she said warmly. “Come on, let’s follow her. We have as much right to go that way as she has, and we must go someway anyway.”

“All right; lead the way,” Hazel said with smiling emphasis on the “way” to direct attention to Katherine’s phonetic repetition.

The latter started along the path that had been taken by the girl and her frightened prisoner, and Hazel followed. The two in advance60 were by this time out of sight beyond a thicket of bushes and small trees, but Katherine and Hazel did not hasten their steps, as they preferred to trust to the path to guide their steps rather than the view of the persons they sought to follow. In fact, they preferred to trust to the element of chance rather than run a risk of arousing the suspicion of the cold-faced girl with the perfume.

Only once did they catch sight of the boy and his captor in the course of their hesitating pursuit, and this view was so satisfactory that they stopped short in order to avoid possible detection if the girl should look back. A turn in the path brought them to the hip of the elevation where the ground began to slope down to the lake and near the downward bend of this beach-hill was a rustic cottage, with an equally rustic garage to the rear and on one side a cleared space for a tennis court. At the door of the cottage was the girl with the pleated skirt and white sailor hat, still leading the now submissive but quivering youth.

“Fine!” Katharine exclaimed under her breath. “Things have turned out just right. If that should prove to be the Graham home we couldn’t wish for better luck. Come on; let’s back through the timber and approach this place from another direction. They mustn’t suspect that we followed that girl and the little boy.”

CHAPTER XII.

THE MAN IN THE AUTO.

Cautiously Katherine and Hazel withdrew from the path into a thicket and thence retreated along the path by which they had approached the house. They continued their retreat to the point where the path joined the automobile road and where grew the thicket within which they had discovered the frightened runaway child.

“Now, I tell you what we ought to do,” Katherine said. “We ought to follow this road about a mile, maybe, to get a view of the lay of the land and then return to this spot, or near it. We can get the information we want after we learn more of the camping possibilities of this neighborhood and can talk intelligently when we begin to make inquiries.”

“And when we get back,” Hazel added, “we’ll go to some neighboring house and ask all about who lives here and who lives there, and, of course, we’ll be particular to ask the name of the family where that icy bottle of perfume lives.”

“That’s the very idea,” Katherine agreed enthusiastically. “But we haven’t any time to waste, for it is nearly 12 o’clock now, and we have only a little more than an hour to work in if the motorboat arrives on time. We’d62 better not try to walk a mile—half a mile will be enough, maybe a quarter—just enough to enable us to talk intelligently about the lay of the land right around here.”

They walked north along the road nearly half a mile, found a path which led directly toward the lake, followed it until within view of the water’s edge, satisfied themselves that there were several excellent camping places along the shore in this vicinity and then started back. They had passed three or four cottages on their way and at one of these they stopped to make inquiries as planned.

A pleasant-faced woman in comfortable domestic attire met them at the door and answered their questions with a readiness that bespoke familiarity with the neighborhood and acquaintance with her neighbors. Katherine and Hazel experienced no slight difficulty in concealing their eager satisfaction when Mrs. Scott, the woman they were questioning, said:

“The people who have the cottage just north of us are the Pruitts of Wilmington, those just south of us are the Ertsmans of Richmond, and those just south of the Ertsmans are the Grahams of Baltimore, I think. I am not very well acquainted with that family. I am sure we would be delighted to have a group of Camp Fire Girls near us and you ought to have no difficulty in getting permission to pitch your tents. This land along here belongs to an estate which is managed by a man63 living in Philadelphia. He is represented here by a real estate man, Mr. Ferris, of Twin Lakes. He probably will permit you to camp here for little or nothing.”

The girls thanked the woman warmly for this information and then hurried away.

“We don’t need to call at the Graham cottage now,” Hazel said as they hastened back to the road. “We have all the preliminary information that we want. The next thing for us to do is to get back to the Point and meet the boat when it comes in and have a talk with the other girls. I suppose our first move then ought to be to go to Twin Lakes and get permission from that real estate man, Ferris, to pitch our tents on the land he has charge of.”

The two girls kept up their rapid walk until within a few hundred feet of the drive that led from the main road to the cottage occupied by the Grahams. Then they slowed up a little as they saw an automobile approaching ahead of them. The machine also slowed up somewhat as it neared the drive. Suddenly Hazel exclaimed, half under her breath:

“It’s going to stop. I wonder what for?”

“Yes, and there’s something familiar in that man’s appearance,” Katherine said slowly. “Why——”

She did not finish the sentence, for the automobile was so near she was afraid the driver would hear her. But there was no need for her to say what she had in her mind to say. Hazel64 recognized the man as soon as she did.

“Be careful,” Katherine warned. “Don’t let him see that we know him. Just pass him as you would a perfect stranger.”

But they did not pass the automobile as expected. Although slowing up, the machine did not stop, and for the first time the girls realized the probable nature of the man’s visit to Stony Point.

“O Hazel!” Katherine whispered; “he’s turning in at the Graham place.”

“I bet he’s come here to warn them against us,” Hazel returned.

“It must be something of the kind,” Katherine agreed, and then the near approach to the automobile rendered unwise any further conversation on the subject.

The girls were within 100 feet of the machine as it turned in on the Graham drive and found that they had all they could do to preserve a calm and unperturbed demeanor as they met the keen searching gaze of the squint eyes of Pierce Langford, the lawyer from Fairberry.

CHAPTER XIII.

A NONSENSE PLOT.

Katherine and Hazel walked past the drive, into which Attorney Langford’s automobile had turned, apparently without any concern or interest in the occupant of the machine. But after they had advanced forty or fifty yards beyond the drive, Hazel’s curiosity got the best of her and she turned her head and looked back. The impulse to do this was so strong, she said afterward, that it seemed impossible for her to control the action. Her glance met the gaze of the squint eyes of the man in the auto.

“My! that was a foolish thing for me to do,” she said as she quickly faced ahead again. “I suppose that look has done more damage than anything else since we started from Fairberry. And to think that I above all others should have been the one to do it. I’m ashamed of myself.”

“Did he see you?” Katherine inquired.

“He was looking right at me,” Hazel replied; “and that look was full of suspicion and meaning. There’s no doubt he’s on our trail and suspects something of the nature of our mission.”

“Oh don’t let that bother you,” Katherine advised. “There’s no reason why he should jump to a conclusion just because you looked back at him. That needn’t necessarily mean66 anything. But if you let it make you uneasy, you may give us dead away the next time you meet him.”

“I believe he knows what our mission here is already,” was Katharine’s fatalistic answer.

“If that’s the case, you needn’t worry any more about what you do or say in his presence,” said Hazel. “We might as well go to him and tell him our story and have it all over with.”

“I don’t agree with you,” Katherine replied. “I believe that the worst chance we have to work against is the probability of suspicion on his part. I don’t see how he can know anything positively. He probably merely learned of our intended departure for Twin Lakes and, knowing that the Grahams were spending the summer here, began to put two and two together. I figure that he followed us on his own responsibility.”

“And that his visit at the Graham cottage today is to give them warning of our coming,” Hazel added.

“Yes, very likely,” Katherine agreed. “I’d like to hear the conversation that is about to take place in that house. I bet it would be very interesting to us.”

“No doubt of it,” said the other; “and it might prove helpful to us in our search for the information we were sent to get.”

“Don’t you think it strange, Hazel, that your aunt should select a bunch of girls like us to do so important a piece of work as67 this?” Katherine inquired. This question had puzzled her a good deal from the moment the proposition had been put to her. Although she had received it originally from Mrs. Hutchins even before the matter had been broached to Hazel, she had not questioned the wisdom of the move, but had accepted the role of advocate assigned to her as if the proceeding were very ordinary and commonsensible.

“If you hadn’t restricted your remark to ‘a bunch of girls like us’, I would answer ‘yes’,” Hazel replied; “I’d say that it was very strange for Aunt Hannah to select a ‘bunch of girls’ to do so important a piece of work as this. But when you speak of the ‘bunch’ as a ‘bunch of girls like us,’ I reply ‘No, it wasn’t strange at all’.”

“I’m afraid you’re getting conceited, Hazel,” Katherine protested gently. “I know you did some remarkable work when you found your aunt’s missing papers, but you shouldn’t pat yourself on the back with such a resounding slap.”

“I wasn’t referring to myself particularly,” Hazel replied with a smile suggestive of “something more coming.” “I was referring principally to my very estimable Camp Fire chums, and of course it would look foolish for me to attempt to leave myself out of the compliment. I suppose I shall have to admit that I am a very classy girl, because if I weren’t, I couldn’t be associated with such a classy bunch—see? Either I have to be classy or68 accuse you other girls of being common like myself.”

“I’m quite content to be called common,” said Katherine.

“But I don’t think you are common, and that’s where the difficulty comes in.”

“Won’t you be generous and call me classy, and I’ll admit I’m classy to keep company with my classy associates, and you can do likewise and we can all be an uncommonly classy bunch of common folks.”

“If we could be talking a string of nonsense like this every time we meet Mr. Langford, we could throw him off the track as easy as scat,” said Hazel meditatively. “What do you say, Katherine?—let’s try it the next time he’s around: We’ll be regular imp—, inp— What’s the word—impromptu actors.”

“We mustn’t overdo it,” Katherine cautioned.

“Of course not. Why should we? We’ll do just as we did this time—let one idea lead on to another in easy, rapid succession. Think it over and whenever you get an idea pass it around, and we’ll be all primed for him. It’ll be lots of fun if we get him guessing, and be to our advantage, too.”

Hazel and Katherine reached the Point in time to see the motorboat containing the other members of the Fire approaching about a mile away. They did not know, of course, who were in the boat, and as it was deemed wise not to indulge in any demonstrations, no69 one on either side did any signalling; but they were not long in doubt as to who the passengers were. A flight of steps led from the top of the point to the landing, and the two advance spies, as they were now quite content to be called, walked down these and were waiting at the water’s edge when the boat ran up along the pile-supported platform.

CHAPTER XIV.

SPARRING FOR A FEE.

Pierce Langford drove the automobile, in which he made his first trip to Stony Point, up to the end of the drive near the Graham cottage, and advanced to the front entrance. The porch on which he stood awaiting the appearance of someone to answer his knock—there was no bell at the door—was bordered with a railing of rough-hewn, but uniformly selected, limbs of hard wood or saplings. The main structure of the house was of yellow pine, but the outer trimmings were mainly of such rustic material as the railing of the porch.

The front door was open, giving the visitor a fairly good view of the interior. The front room was large and fairly well furnished with light inexpensive furniture, grass rugs and an assortment of nondescript, “catch-as-catch-can,” but not unattractive, art upon the walls. Langford, who was not a sleepy schemer, was able to get a good view of the room before any one appeared to answer his knock.

It was a woman who appeared, a sharp featured, well-dressed matron with a challenging eye. Perhaps no stranger, or person out of the exclusive circle that she assumed to represent ever approached her without being met71 with the ocular demand, “Who are you?”

Pierce Langford recognized this demand at once. If he had been of less indolent character this unscrupulous attorney might have made a brilliant success as a criminal lawyer in a metropolis. The fact that he was content with the limitations of a practice in a city of 3,500 inhabitants, Fairberry, his home town, was of itself indicative of his indolence. And yet, when he took a case, he manifested gifts of shrewdness that would have made many another lawyer of much greater practice jealous.

Attorney Langford’s shrewdness and indolence were alternately intermittent. When the nerve centers of his shrewdness were stimulated his indolence lapsed and he was very much on the alert. The present was one of those instances. He knew something, by reputation, of the woman who confronted him. He had had indirect dealing with her before, but he had never met her. However, he was certain that she would recognize his name.

“Is this Mrs. Graham?” he inquired, although he scarcely needed to ask the question.

“It is,” she replied with evidently habitual precision.

“My name is Langford—Pierce Langford,” he announced, and then waited for the effect of this limited information.

The woman started. It was a startled start. The challenge of her countenance wavered;72 the precision of her manner became an attitude of caution.

“Not—not Pierce Langford of—of—?” she began.

The man smiled on one side of his mouth.

“The very one, none other,” he answered cunningly. “Not to be in the least obscure, I am from the pretty, quiet and somewhat sequestered city of Fairberry. You know the place, I believe.”

“I’ve never been there and hope I shall never have occasion to go to your diminutive metropolis,” she returned rather savagely.

“No?” the visitor commented with a rising inflection for rhetorical effect. “By the way, may I come in?”

“Certainly,” Mrs. Graham answered recovering quickly from a partial lapse of mindfulness of the situation.

The woman turned and led the way into the house and the visitor followed. Mrs. Graham directed the lawyer to a reed rockingchair and herself sat down on another reed-rest of the armchair variety. The woman by this time had recovered something of her former challenging attitude and inquired:

“Well, Mr. Langford, what is the meaning of this visit?”