« back

|

|

PECK’S BAD BOY ABROAD

By Hon. Geo. W. Peck

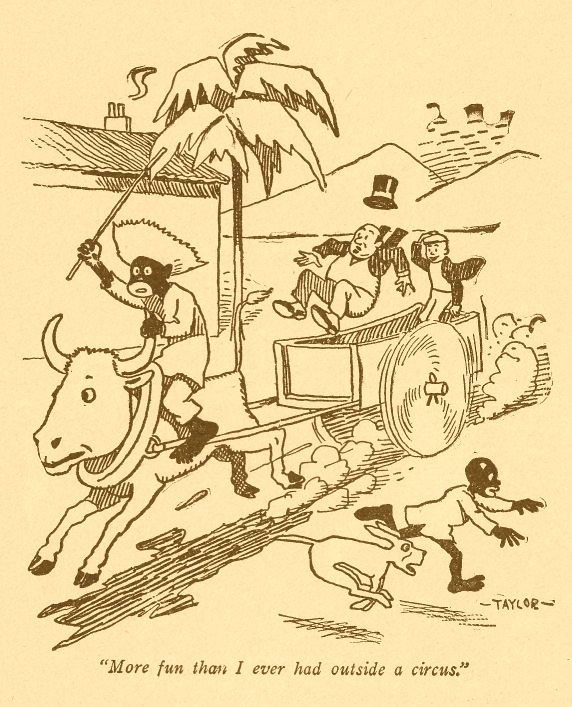

Being a Humorous Description of the Bad Boy and His Dad in Their Journeys Through Foreign Lands, Their Visits to Crowned Heads, the Manners and Customs of the People, and the Bad Boy’s Never Ending Efforts to Provide Fun No Matter Where He Is.

Profusely Illustrated by D. S. Groesbeck and R. W. Taylor

THOMPSON & THOMAS - 1904

Contents

List of Illustrations

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

The Bad Boy and His Chum Call on the Old Groceryman After Being Away at

School—The Bad Boy’s Dad in a Bad Way

CHAPTER II.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Ready for Their Travels—The Bad Boy Labels the

Old Man’s Suit Case—How the Cowboys Made Him Dance Once

CHAPTER III.

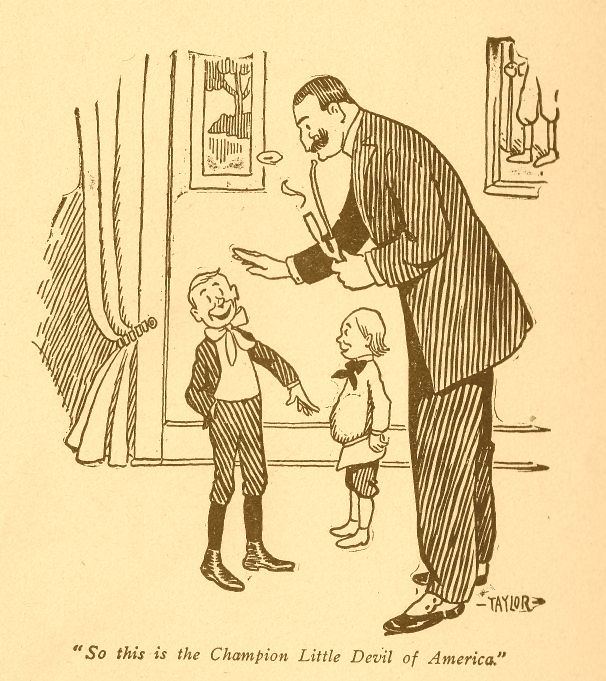

The Bad Boy Writes About the Fun They Had Going to Washington—He

and His Dad Call on President Roosevelt—The Bad Boy Meets One of the

Children and They Disagree

CHAPTER IV.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Visit Mount Vernon—Dad Weeps at the Grave of

the Father of Our Country

CHAPTER V.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Have Dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria—The Bad Boy

Orders Dinner—The Old Man Gets Stuck—Tries to Rescue a Countess in

Distress

CHAPTER VI.

The Bad Boy Writes the Old Groceryman About Ocean Voyages—His Dad Has

an Argument Over a Steamer Chair.

CHAPTER VII.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Eat Fog—Call on Astor—A Dynamite Outrage

CHAPTER VIII.

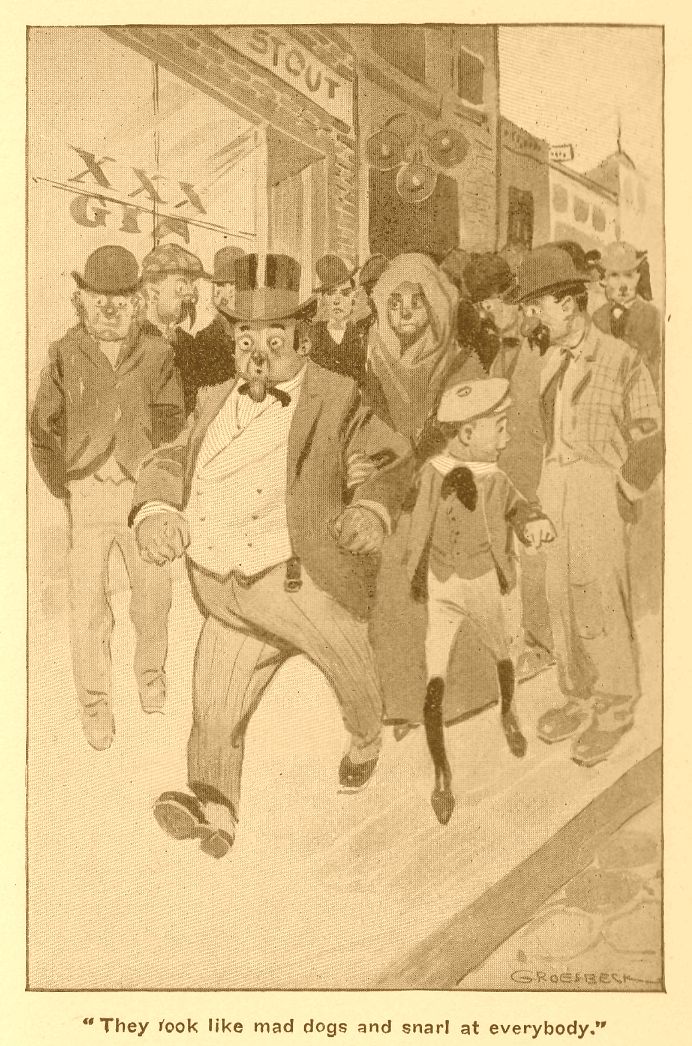

The Bad Boy Writes About the Craze for Gin in the White-chapel

District—He Gives His Dad a Scare in the Tower of London

CHAPTER IX.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Call on King Edward and Almost Settle the Irish

Question

CHAPTER X.

The Bad Boy Writes of Ancient and Modern Highwaymen—¦ They Get a Taste

of High Life in London and Dad Tells the Story of the Picklemaker’s

Daughter

CHAPTER XI.

The Bad Boy Writes About Paris—Tells About the Trip Across the English

Channel—Dad Feeds a Dog and Gets Arrested

CHAPTER XII.

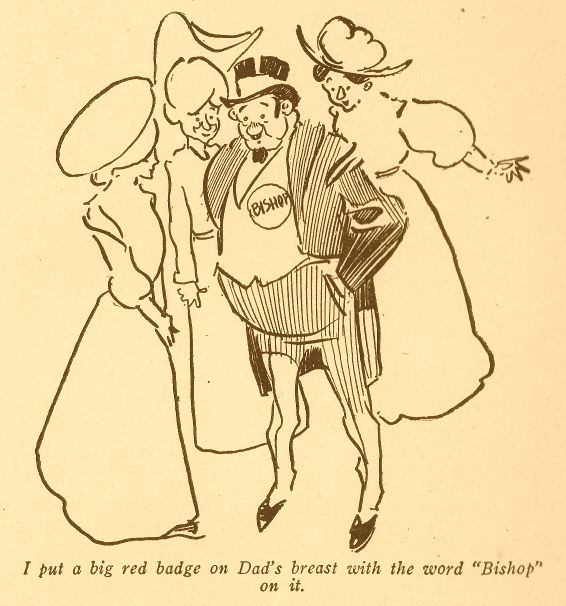

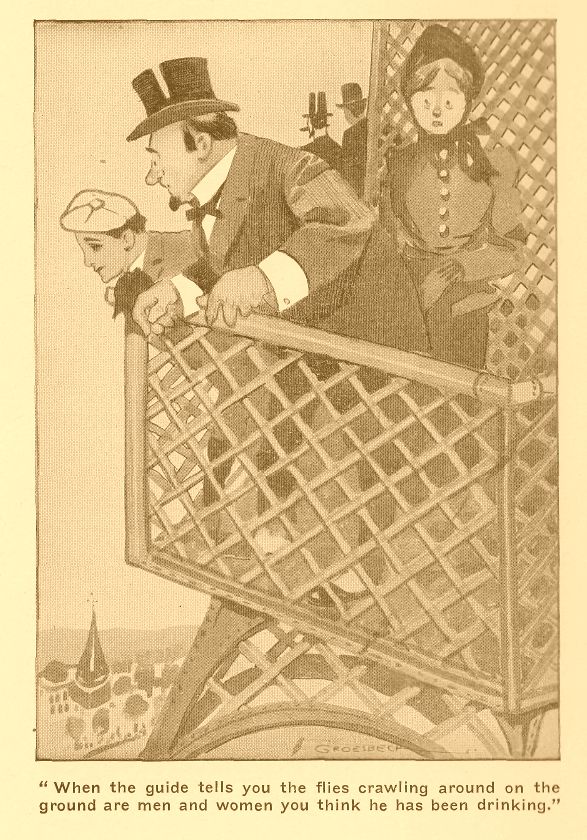

The Bad Boy’s Second Letter from Paris—Dad Poses as a Mormon Bishop

and Has to Be Rescued—They Climb the Eiffel Tower and the Old Man Gets

Converted

CHAPTER XIII.

The Bad Boy’s Dad and a Man from Dakota Frame Up a Scheme to Break the

Bank, But They Go Broke—The Party in Trouble

CHAPTER XIV.

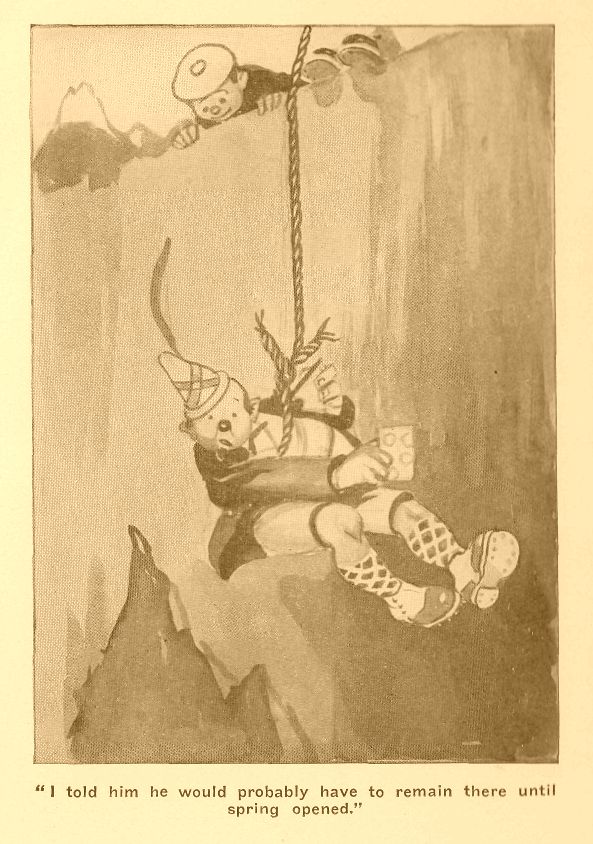

The Bad Boy and His Dad Have an Automobile Ride—They Run Over a

Peasant—Climb “Glaziers”—Dad Falls Over a Precipice, But Is Rescued by

the Guides After a Hard Time of It

CHAPTER XV.

Dad Plays He Is an Anarchist—They Give Alms to the Beggars and the Bad

Boy Ducks a Gondolier and His Dad in the Grand Canal

CHAPTER XVI.

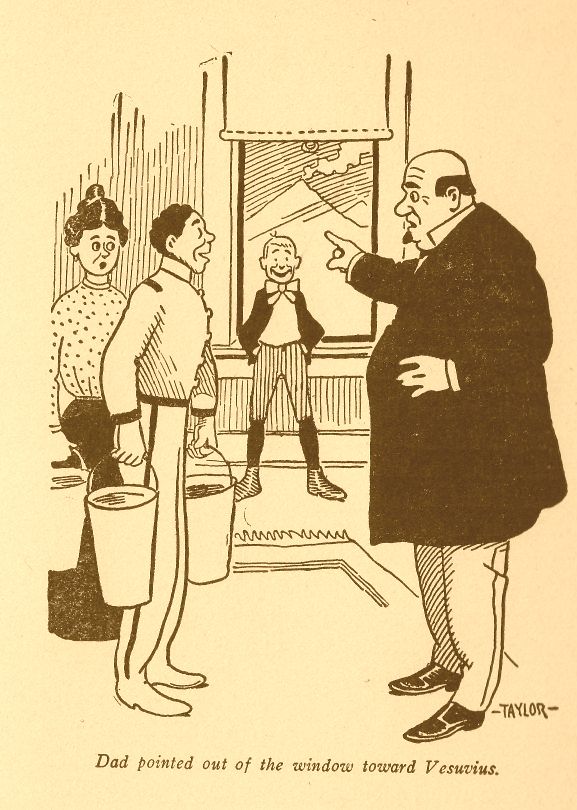

The Bad Boy Writes from Naples—Dad Sees Vesuvius and Calls the Servants

to Put Out the Fire—They Have Trouble with a “Dago” in Pompeii

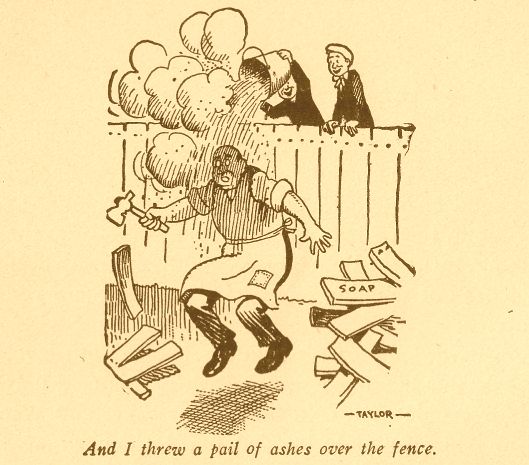

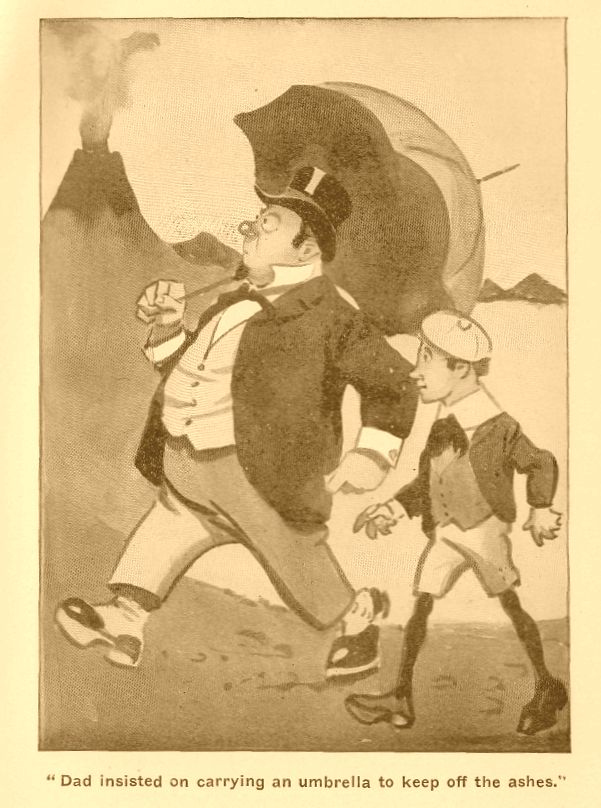

CHAPTER XVII.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Climb Vesuvius—A Chicago Lady Joins the Party

and Causes Trouble

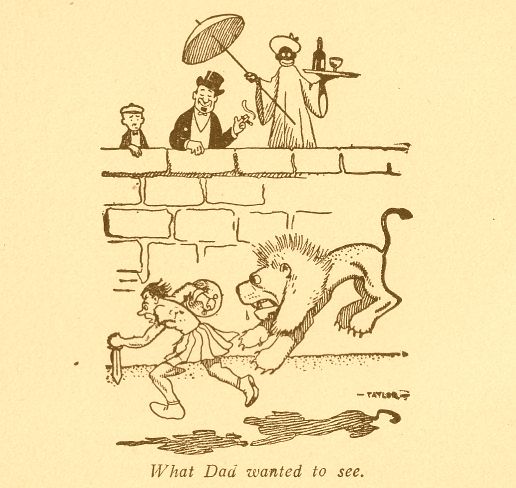

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Bad Boy Makes Friends with Some Italian Children—Dad is Chased by

Lions from the Coliseum—” Not Any More Rome for Papa,” says Dad

CHAPTER XIX.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Visit the Pope—They Bow to, the King of Italy

and His Nine Spots—Dad Finds That “The Catacombs” Is Not a Comic Opera

CHAPTER XX.

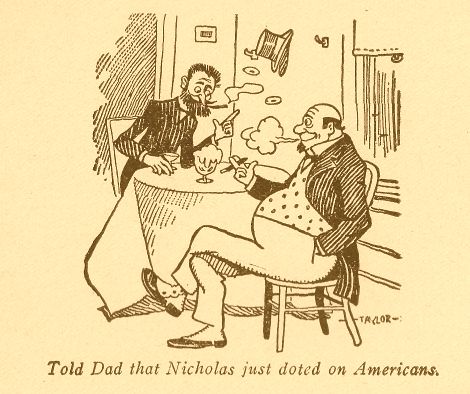

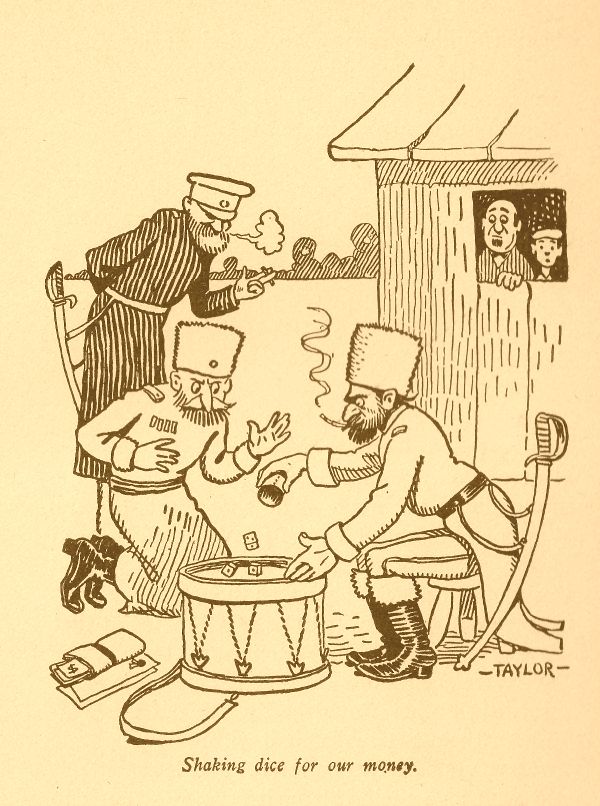

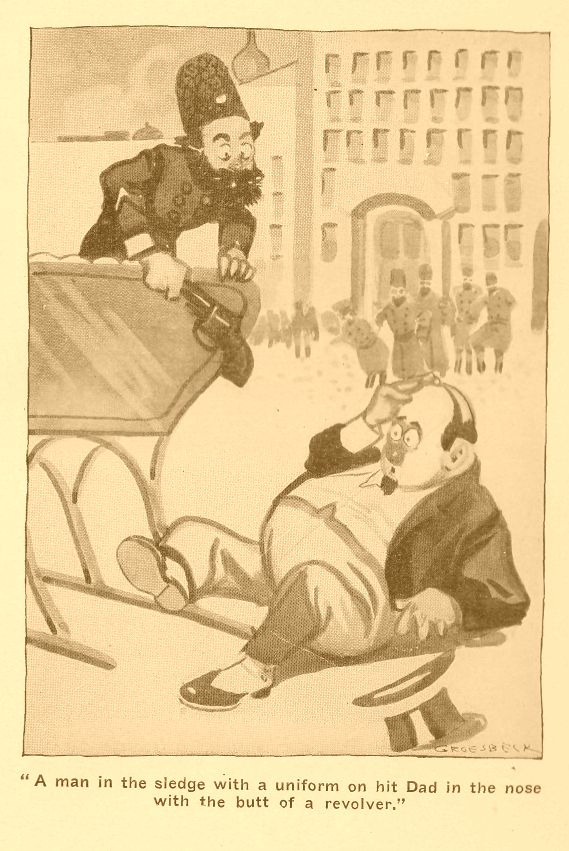

The Bad Boy Tells About the Land of the Czar and the Trouble They Had to

Get There—Dad Does a Stunt and Mixes It Up with the People and Soldiers

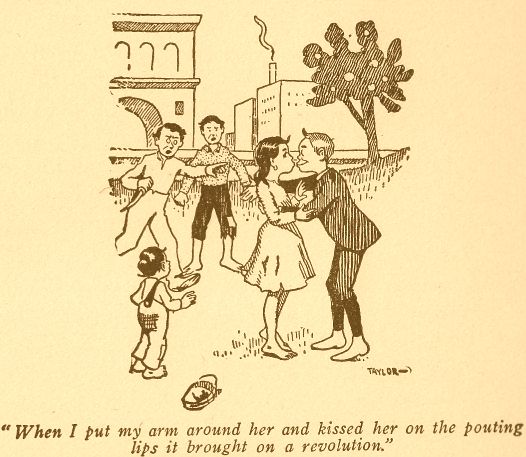

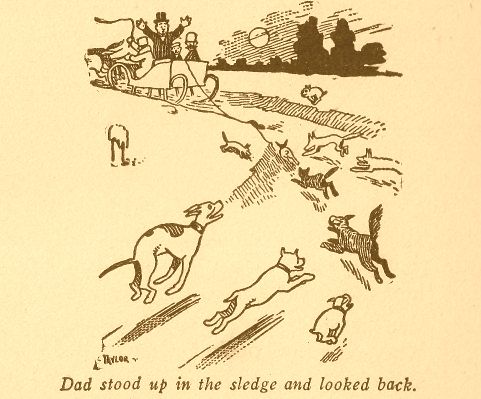

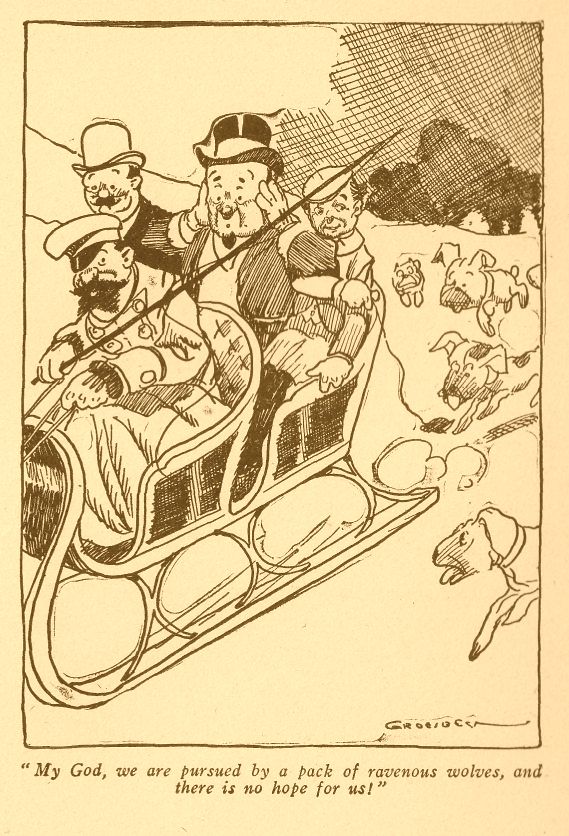

CHAPTER XXI.

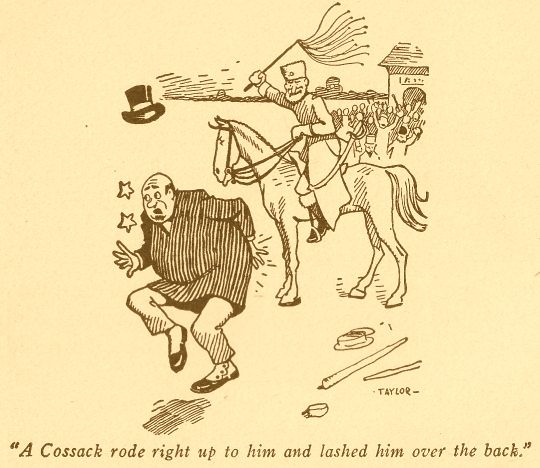

Dad Sees a Russian Revolution and Faints—‘The Bad Boy Arranges a Wolf

Hunt—Dad Threatens to Throw the Boy to the Wolves

CHAPTER XXII.

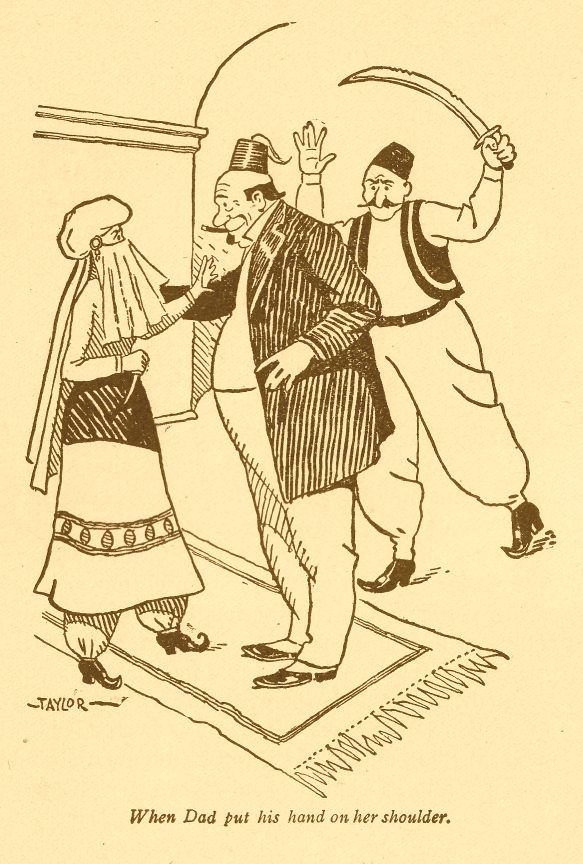

Dad Wears His Masonic Fez in Constantinople—They Find the Turks

Sensitive on the Dog Question—A College Yell for the Sultan Sends Him

Into a Fit

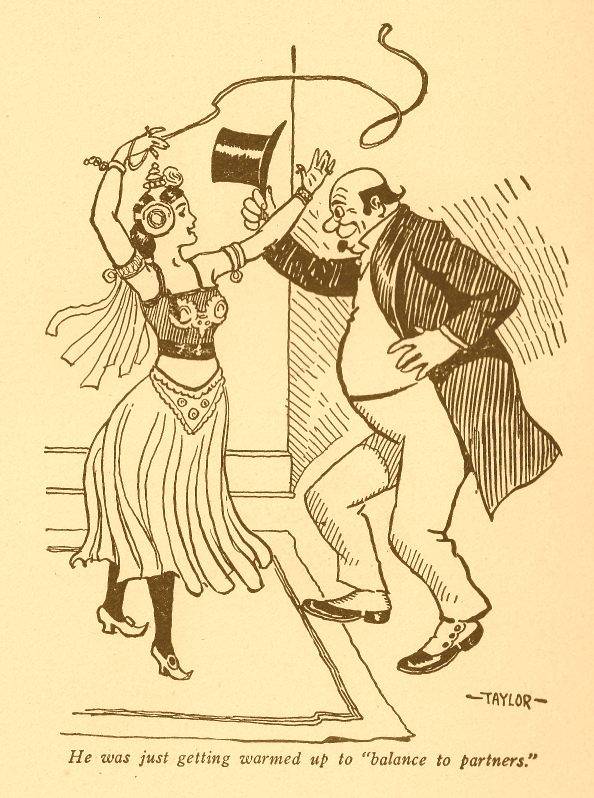

CHAPTER XXIII.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Meet the Cream of the Harem—“Little Egypt” Does

a Dancing Stunt—The Sultan Wants to Send Fifty Wives to the President

CHAPTER XXIV.

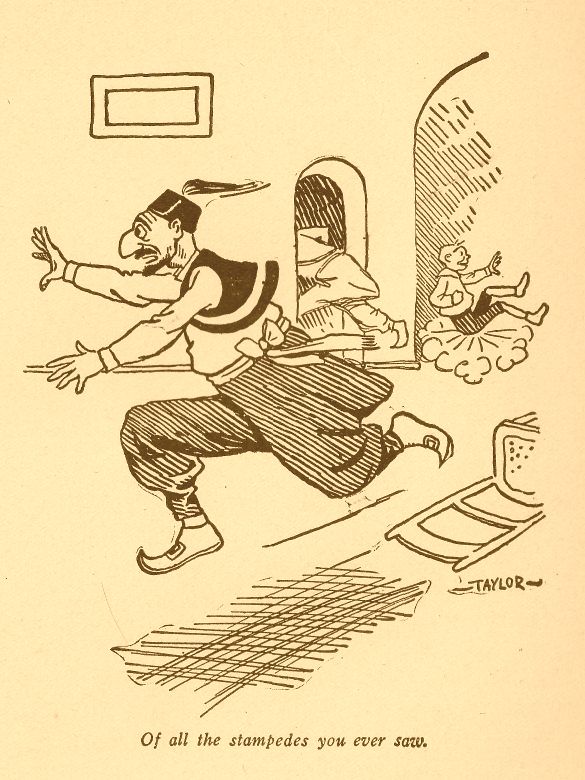

The Bad Boy and His Dad Arrive in Cairo—At the Hotel They Meet Some

Egyptian Princesses—Dad Rides a Camel to the Pyramids and Meets with

Difficulties

CHAPTER XXV.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Climb the Pyramids—The Bad Boy Lights a Cannon

Cracker in Rameses’ Tomb—They Flee from Egypt in Disguise

CHAPTER XXVI.

The Bad Boy Writes About Gibraltar—The Irish-English Army—How He Would

Take the Fortress—Dad Wants to Buy the “Rock”

CHAPTER XXVII.

The Bad Boy Writes of Spain—They call On the King and the Bad Boy Is At

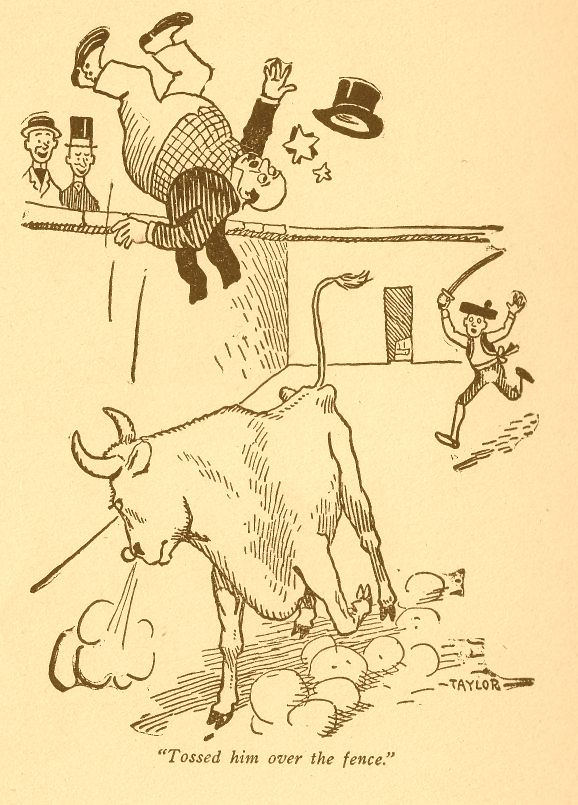

It Once More—They See a Bull Fight and Dad Does a Turn

CHAPTER XXVIII.

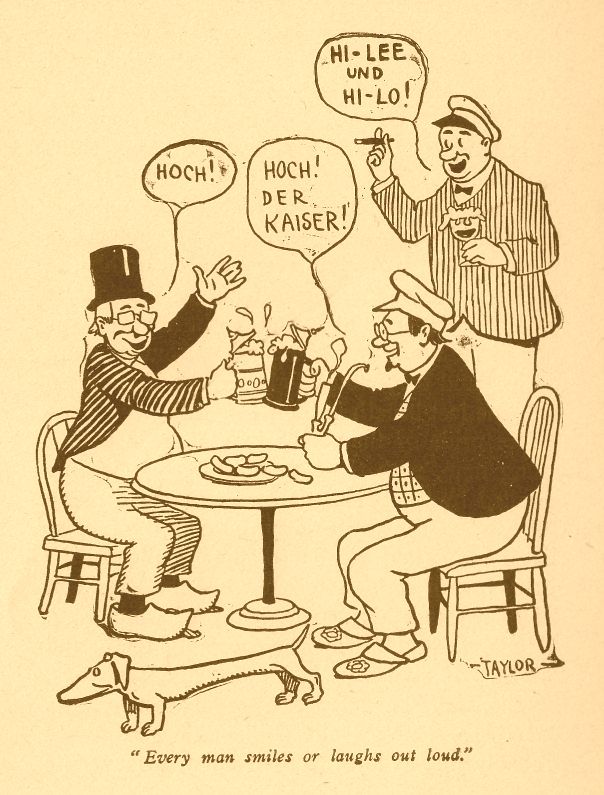

The Bad Boy and His Dad at Berlin—They Call On Emperor William and His

Family and the Bad Boy Plays a Joke on Them All

CHAPTER XXIX.

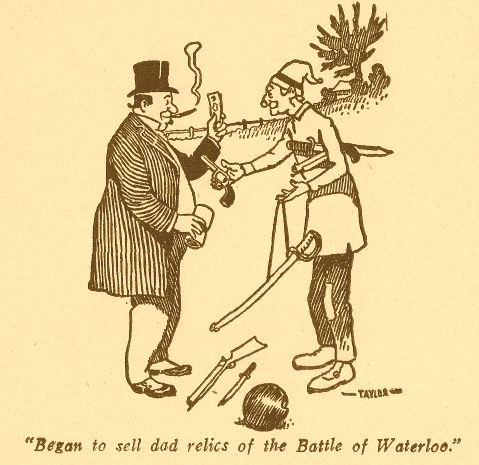

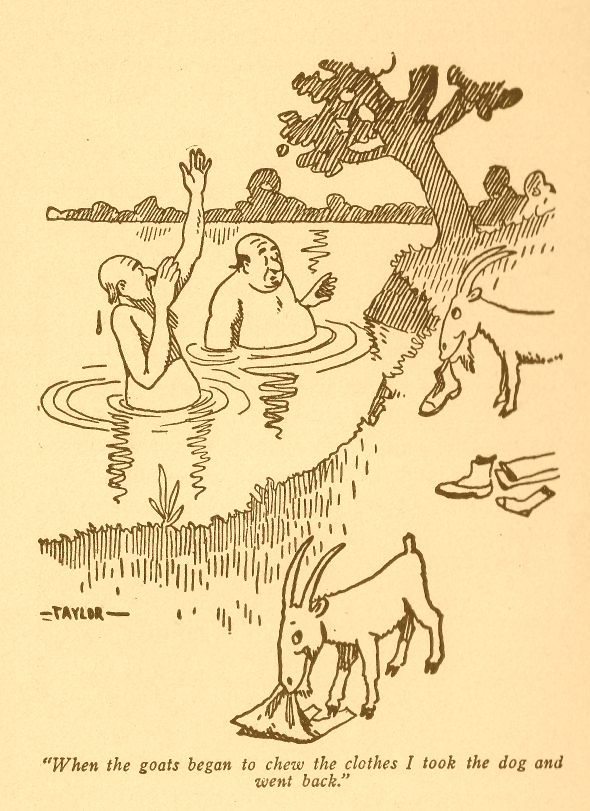

The Bad Boy Writes from Brussels—He and Dad See the Field of Waterloo

and Call on King Leopold, and Dad and the King Go in for a Swim—The Bad

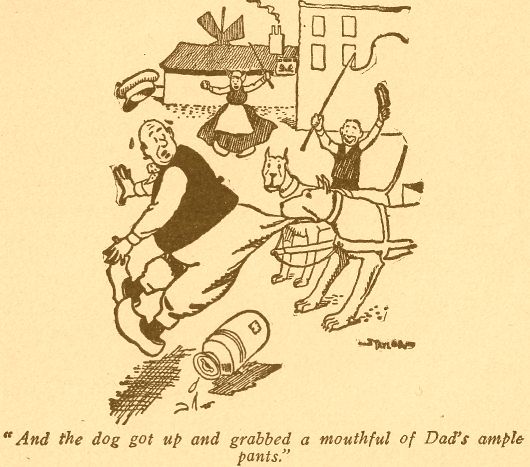

Boy, a Dog and Some Goats Do the Rest

CHAPTER XXX.

The Bad Boy’s Delayed Letter About Holland and Cuba—Dad and the Boy Go

for a Drive in a Dog-Cart—They Have a Great Time—Land in Cuba and See

the Island We Fought For

PECK’S BAD BOY ABROAD.

CHAPTER I.

The Bad Boy and His Chum Call on the Old Grocery-man After

Being Away at School—The Bad Boy’s Dad in a Bad Way.

The bad boy had been away to school, but the illness of his father had called him home, and for some weeks he had been looking about the old town. He had found few of his old friends. His father had recovered somewhat from his illness, and one day he met his old chum, a boy of his own age. The bad boy and the chum got busy at once, talking over the old times that tried the souls of the neighbors and finally the bad boy asked about the old groceryman, and found that the old man still held out at the old stand, with the same old stock of groceries, and they decided to call upon him, and surprise him. So after it began to be dark they entered the store, and found the old groceryman sitting on a cracker box by the stove, stroking the back of an old maltese cat that had a yellow streak on the back, where it had been singed by crawling under the red-hot stove. As the boys entered the store the cat raised its back, its tail became as large as a rolling pin, and the cat began to spit, while the old groceryman held up both hands and said:

“Don’t shoot, please, but one of you go behind the counter and take what there is in the cash drawer, while the other one can reach into my pistol pocket and release my pocketbook. This is the fifth time I have been held up this year, and I have got so if I am not held up about so often I can’t sleep nights.”

“O, put down your hands and straighten out that cat’s back,” said the bad boy, as he slapped the old groceryman on the back so hard his spine cracked like a frozen sidewalk. “Don’t you know us, you old geezer? We are the only and original Peck’s Bad Boy and his Chum, come to life, and ready for business,” and the two boys danced a jig on the floor, covered an inch thick with the spilled sugar of years ago, the molasses that had strayed from barrel, and the general refuse of the dirty place, which had become as hard as asphalt.

“O, dear, it is worse than I thought,” said the old groceryman as he laughed a hysterical laugh through the long whiskers, and he hugged the boys as though he had a liking for them, notwithstanding the suffering they had caused him. “By gosh, I thought you were nothing but common robbers, who just wanted my money. You are old friends, and can have the whole place,” and he poured some milk into a basin for the cat, but the animal only looked at the two boys as though she knew them, and watched them to see what was coming next.

The bad boy looked around the old grocery, which had not changed a particle during the time he had been away, the same old box of petrified prunes, the dried apples that could not be cut with a hatchet, the canned stuff on the shelves had become so old that the labels had curled up and fallen off, so it must have been a guess with the old groceryman whether he was selling a can of peas or tomatoes, and the old fellow standing there as though the world had gone off and left him, as his customers had.

“Well, wouldn’t this skin you,” said the bad boy, as he took up a dried prune and tried to crack it with a hatchet on a two-pound weight, turning to his chum who was stroking the singed hair of the old cat the wrong way. “Say, old man, you ought to get a hustle on you. Why don’t you clean out this shebang, and put in a new stock, of goods, and have clerks with white aprons on, and a girl bookkeeper, and goods that people will buy and eat and not get sick? There is a grocery down street that is as clean as a whistle, and I notice all your old customers go there. Why don’t you keep up with the times?”

“O, I ain’t running a dude place,” said the old man, as he took a piece of soft coal and put it in the old round stove, and wiped the black off his hands on his trousers. “I am trying to get rid of my customers. I have got money enough to live on, and I just stay here waiting for the old cat to die. I have only got six customers left, and one of them has got pneumonia, and is going to die, then there will be only five. When they are all gone I shall sit here by the stove until the end comes. There is nothing doing now to keep me awake, since you boys quit getting me mad. Say, boys, do you know, I haven’t been real mad since you quit coming here. The only fun I have had is swearing at my customers when they stick up their noses at my groceries. It’s the funniest thing, when I tell an old customer that if they don’t like my goods they can go plum to thunder, they get mad and go somewhere else to trade. Times must be changing. Years ago, the more I abused customers the more they liked it, and I just charged the goods to them with a pencil on a piece of brown wrapping paper. I had four cracker boxes full of brown wrapping paper with things charged on the paper against customers, but when anybody wanted to pay their account it made my head ache to find it, and so one day I balanced my books by using the brown wrapping paper to kindle the fire. If you ever want to get even with the world, easy, just pour a little kerosene on your accounts, and put them in the stove. I have never been so free from worry as I have since I balanced my books in the stove. Well, I suppose you have come home on account of your dad’s sickness,” said the old groceryman, turning to the bad boy, who had written a sign, ‘The Morgue,’ and pinned it on the window. “I understand your dad had an operation performed on him in a hospital. What did the doctors take out of him?”

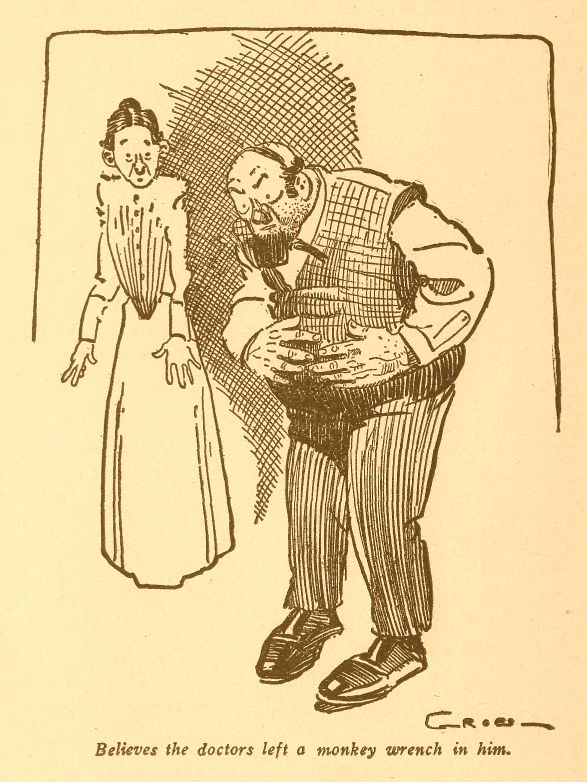

“Dad had an operation all right,” said the bad boy, “but he is not as much interested in what they took out of him, as what he thinks they left in. They said they removed his appendix, and I guess they did, for dad showed me the bill the doctors rendered. The bill was big enough so they might have taken out a whole lot more. If I had been home I would never have let him be cut into, but ma insisted that he must have an operation. She said all the men on our street, and all that moved in our set, had had operations, and she was ashamed to go out in society and be forced to admit that dad never had an operation, She told dad that he could afford it better than half the people that had operations, and that a scar criss-cross on the stomach was a badge of honor. He never got a scar in the army, and she simply would not be able to look people in the face unless dad was operated on. Dad always was subject to stomach ache, but until appendicitis became fashionable he had always taken a mess of pills, and come out all right, but ma diagnosed the case the last time he was doubled up like a jack-knife, and dad was hustled off to the hospital, and they didn’t do a thing to him.

“He told me about it since I came home, and now he lays the whole thing to ma, and I have to stand between them. He is going to get even with ma, though. The first time she complains of anything going on inside of her works, he is going to send her right to a hospital and have the doctors do their worst. Dad said to me, says he:

“‘Hennery, if you ever feel anything like a caucus being held inside you, don’t you ever go to a hospital, but just swallow a stick of dynamite and light the fuse, then there won’t be anything left inside to bother you afterwards. When I got to the hospital they stripped me for a prize fight, put me on a table made of glass, and rolled me into the operating room, gave me chloroform and when they thought I was all in, they took an axe and chopped me. I could feel every blow, and it is a wonder they left enough of your old dad for you to hug when you came home.’

“Say, it is kind of pitiful to hear dad talk about the things they left in him.”

“What things does he think they left in him,” asked the old groceryman, as he looked frightened, and felt of his stomach, as though he mistrusted there might be something wrong with him, too.

“O, dad has been reading in the papers about doctors that perform operations leaving sponges, forceps, and things inside of patients, when they close up the place, and since dad has got pretty fussy since his operation he thinks they left something in him. Some days he thinks they left a roll of cotton batting, or a pillow, or a bale of hay, but when there is a sharp pain inside he thinks they left a carving knife, but for a week he has settled down to the belief that the doctors left a monkey wrench in him, and he is just daffy on that subject. Says he can feel it turning around, as though it was miscrewing machinery, and he wants to consult a new doctor every day as to what he can take to dissolve a monkey wrench, so it will pass off through the blood and pores of the skin. He has taken it into his head that nothing will save his life except to travel all over the country, and the world. I am to go with him to look after him.”

“By ginger, it’s great! Just think of it. Traveling all over the world and nothing to do but nurse my old dad who thinks he is filled with hardware and carpenter’s tools. Gee! but I wish you could go,” said the bad boy, as he put him arm around his chum. “Maybe we wouldn’t make these foreigners sit up and take an interest in something besides Royalty and Riots.”

“Well,” said the groceryman, “they will have my sympathy with you alone over there.”

“But before you start on the road with your monkey-wrench show, you come in here and let me put up a package of those prunes to take along. They will keep in any climate, and there is nothing better for iron in the blood, such as your dad has, than prunes. Call again, bub, and we will arrange for you to write to your chum from all the places you go with your dad, and he can come in here and read the letters to me and the cat.”

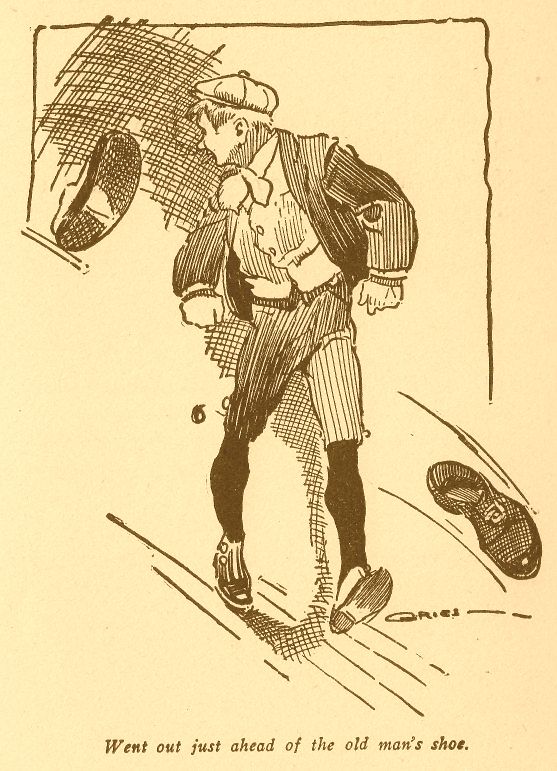

“All right, old Father Time,” said the bad boy, as he drew a mug of cider out of the vinegar barrel, and took a swallow. “But what you want to do is to get a road scraper and drive a team through this grocery, and clean the floor,” and the boys went out just ahead of the old man’s arctic overshoes, as he kicked at them, and then he went back and sat down by the stove and stroked the cat, which had got its back down level again, after its old enemies had gone down the street, throwing snowballs at the driver of a hearse.

“It is a solemn occupation to drive a hearse,” said the bad boy.

“Not so solemn as riding inside,” said the chum.

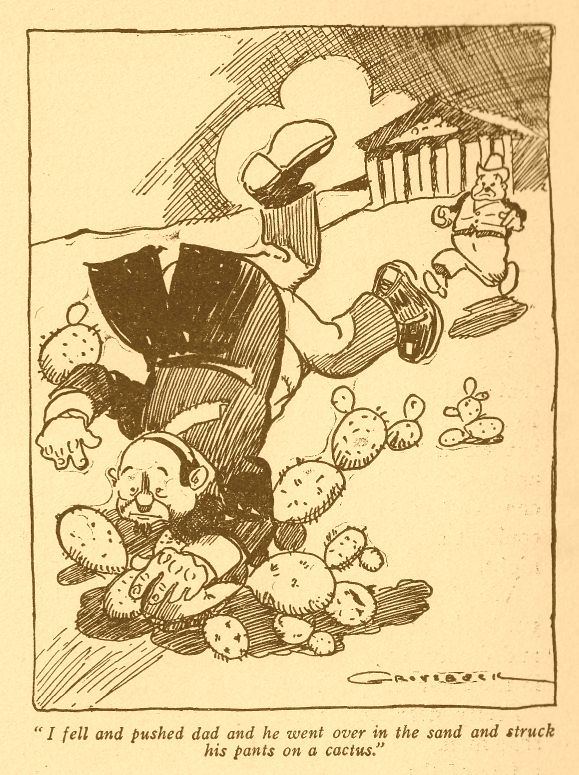

CHAPTER II.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Ready for Their Travels—The Bad Boy

Labels the Old Man’s Suit Case—How the Cowboys Made Him

Dance Once.

The old groceryman was in front of the grocery, bent oyer a box of rutabagas, turning the decayed sides down to make the possible customer think all was not as bad as it might be, when a shrill whistle down the street attracted his attention. He looked in the direction from which it came, and saw the bad boy coming with a suit case in one hand and a sole leather hat box in the other, and the old man went in the store to say a silent prayer, and to lay a hatchet and an ax handle where he could reach them if the worst came.

“Well, you want to get a good look at me now,” said the bad boy, as he dropped the valise on the floor, and put the hat box on the counter, “for it will be months and maybe years, before you see me again.”

“Oh, joy!” said the old groceryman, as he heaved a sigh, and tried to look sorry. “What is it, reform school, or have the police ordered you out of town? I have felt it coming for a long time. This is the only town you could have plied your vocation so long in and not been pulled. Where are you going with the dude suit case and the hat box?”

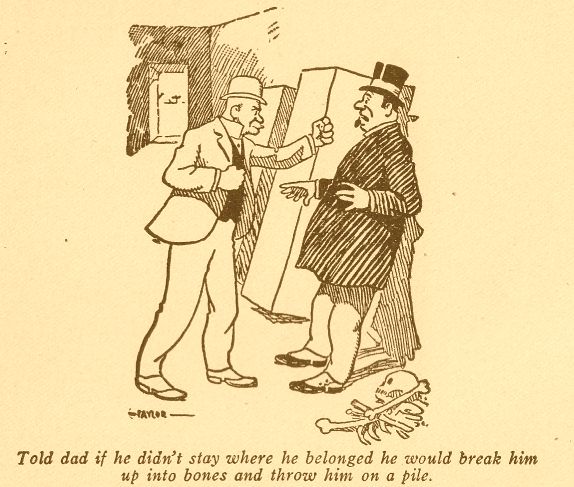

“Oh, dad has got a whole mess more diseases, and the doctors had a conversation over him Sunday, and they say he has got to go away again, right now, and that a sea voyage will brace him up and empty him out so medicine over in Europe can get in its work and strengthen him so he can start back after a while and probably die on the way home, and be buried at sea. Dad says he will go, for he had rather die at sea than on land, ‘cause they don’t have to have any trouble about a funeral, ‘cause all they do is to sew a man up in a piece of cloth, tie a sack of coal to his feet, slide him off a board, and he goes kerplunk down into the salt water about a mile, and stands there on his feet and makes the whales and sharks think he is a new kind of fish.”

“Gee! but that is a programme that appeals to me as sort of uncanny,” said the old man. “Is your dad despondent over the outlook? What new disease has he got?”

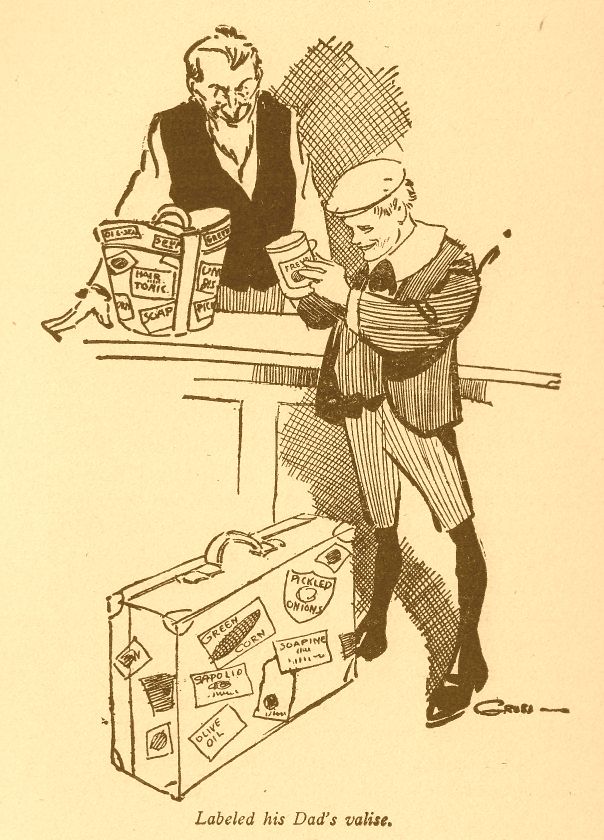

“All of ‘em,” said the boy, as he took a label off a tomato can and pasted it on the end of the suit case. “You take an almanac and read about all the diseases that the medicine advertised in the almanac cures, and dad has got the whole lot of them, nervous prostration, rheumatism, liver trouble, stomach busted, lungs congested, diaphragm turned over, heart disease, bronchitis, corns, bunions, every darn thing a man can catch without costing him anything. But he is not despondent. He just thinks it is an evidence of genius, and a certificate of standing in society and wealth. He argues that the poor people who have only one disease are not in it with statesmen and scholars. Oh, he is all right. He thinks if he goes to Europe all knocked out, he will class with emperors and dukes. Oh, since he had that operation and had his appendix chopped out, he thinks there is a bond of sympathy between him and King Edward that will cause him to be invited to be the guest of royalty. He is just daffy,” and the bad boy took a sapolio label out of a box and pasted it on the other end of the valise.

“What in thunder and lightning are you pasting those labels on your valise for?” said the old man, as the boy reached for a Quaker oats label and a soap advertisement and pasted them on.

“Oh, dad said he wished he had some foreign labels of hotels and things on his valise, to make fellow travelers believe he had been abroad before, and I told him I could fix it all right. You see, if I paste things all over the valise he will think it is all right, ‘cause he is near sighted,” and the boy pasted on a label for 37 varieties of pickles, and then put on an advertisement for hair restorer on the hat box.

“Say, here’s a fine one, this malted milk label, with a New Jersey cow on the corner,” said the old man, as he began to take interest in the boy’s talent as an artist. “And here, try one of these green pea can labels, and the pork and beans legend, and the only soap. Say, if you and your dad don’t create a sensation from the minute you take the train till you get back, you can take it out of my wages. When are you going?”

“To-morrow night,” said the boy, as he put more labels on the hat box, and stood off and looked at them with the eye of an artist. “We go to New York first to stay a few days and see things, and then we take a steamer and sail away, and the sicker dad is the more time I will have to fill up on useful nollig.”

“Hennery,” said the old groceryman, as his chin trembled, and a tear came to his eye. “I want to ask you a favor. At times, when you have been unusually mean, I have thought I hated you, but when I have said something ugly to you, and have laid awake all night regretting it, it has occurred to me that you were about the best friend I had. I think it makes an old man forget his years, to be chummy with a live boy, full of ginger, and I do like you, condemn you, and I can’t help it. Now I want you to write me every little while, on your trip, and I will read your letters to the customers here in the store, who will be lonely until they can hear that you are dead. The neighbors will come in to read your letters, and it will bring me custom. Will you write to me, boy, and pour out your heart to me, and tell me of the different troubles you get your dad into, for surely you cannot help finding trouble over there if you go hunting for it. Promise me, boy.”

“You bet your life I will, old pard,” said the bad boy. “I shall have to have some escape valve to keep from busting. I was going to write to my chum, but he is in love with a telephone girl, and he don’t take any time for pleasure. I will write you about every dutch and duchess we meet, every prince and pauper, and everything. You watch my smoke, and you will think there is a train afire. I hope dad will try and restrain himself from wanting to fight everybody that belongs to any country but America. He has bought one one these little silk American flags to wear in his button hole, and he swears if anybody looks cross-eyed at that flag he will simply cut his liver out, and toast it on a fork, and eat it. He makes me tired, and I know there is going to be trouble.”

“Don’t you think your dad’s mind sort of wanders?” said the old groceryman, in a whisper, “It wouldn’t be strange, after all he has gone through, in raising you up to your present size, if he was a little off his base.”

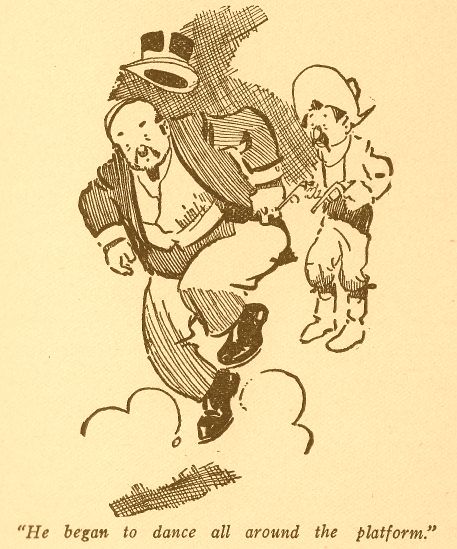

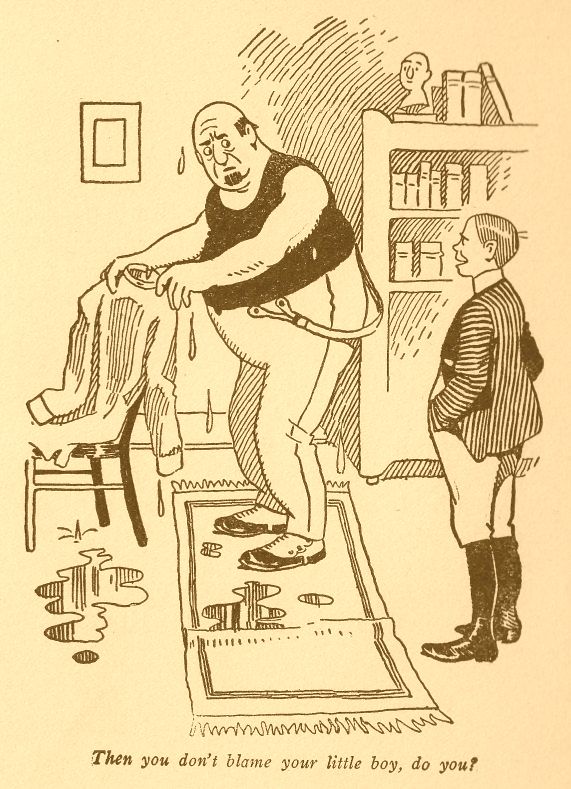

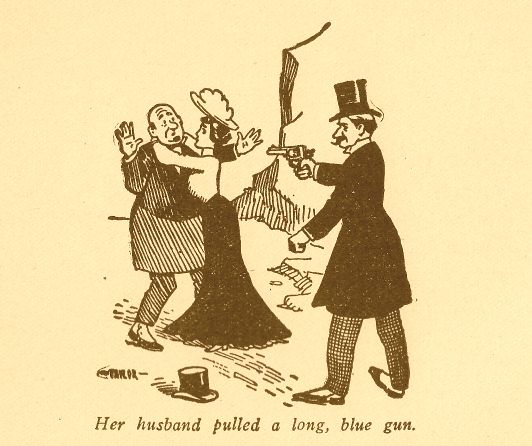

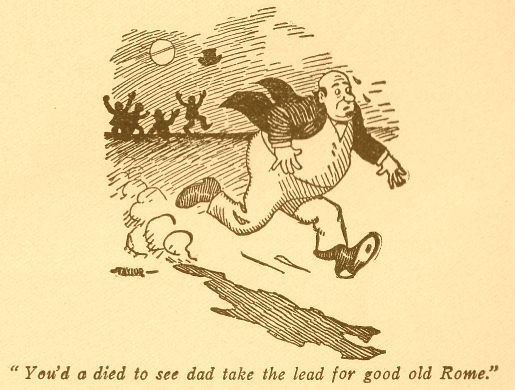

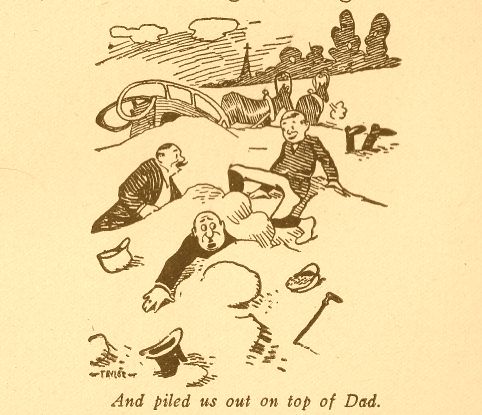

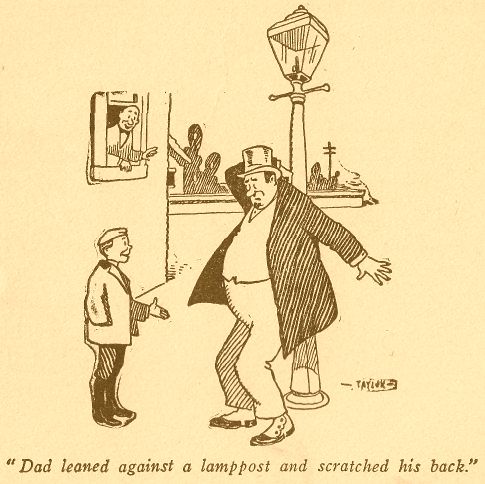

“Well, ma thinks he is bug-house, and the hired girl is willing to go into court and swear to it, and that experience we had coming home from the Yellowstone park some time ago, made me think if he was not crazy he would be before long, You see, we had a hot box on the engine, and had to stay at a station in the bad lands for an hour, and there were a mess of cow boys on the platform, and I told dad we might as well have some amusement while we were there, and that a brake-man told me the cow boys were great dancers, but you couldn’t hire them to dance, but if some man with a strong personality would demand that they dance, and put his hand on his pistol pocket they would all jump in and dance for an hour. That was enough for dad, for he has a microbe that he is a man of strong personality, and that when he demands that anybody do something they simply got to do it, so he walked up and down the platform a couple of times to get his draw poker face on, and I went up to one of the cow boys and told him that the old duffer used to be a ballet dancer, and he thought everybody ought to dance when they were told to, and that if the spell should come on him, and he should order them to dance, it would be a great favor to me if they would just give him a double shuffle or two, just to ease his mind.

“Well, pretty soon he came along to where the cowboys were leaning against the railing, and, looking at them in a haughty manner, he said: ‘Dance, you kiotes, dance,’ and he put his hand to his pistol pocket. Well, sir, I never saw so much fun in my life. Four of the cow boys pulled revolvers and began to shoot regular bullets into the platform within an inch of dad’s feet, and they yelled to him: ‘Dance your own self, you ancient maverick; whoop ‘er up!’ and by gosh! dad was so frightened that he began to dance all around the platform, and it was like a battle, the bullets splintering the boards, and the smoke filling the air, and the passengers looking out of the windows and laughing, and the engineer and fireman looking on and yelling, and dad nearly exhausted from the exertion. I guess if the conductor had not got the hot box put out and yelled all aboard, dad would have had apoplexy.”

“When he let up, the cow boys quit shooting, and he! ’ol aboard the train and started. I stayed in the smoking car with the train butcher for more than an hour, ‘cause I was afraid if I went in the car where dad was he would make some remark that would offend my pride, and when I did go back to the car he just said: ‘Somebody fooled you. Those fellows couldn’t dance, and I knew it all the time.’ Yes, I guess there is no doubt dad is crazy sometimes, but let me chaperone him through a few foreign countries and he will stand without hitching all right. Well, goodby, now, old man, and try and bear up under it, till you get a letter from me,” and the bad boy took his labeled valise and hat box and started.

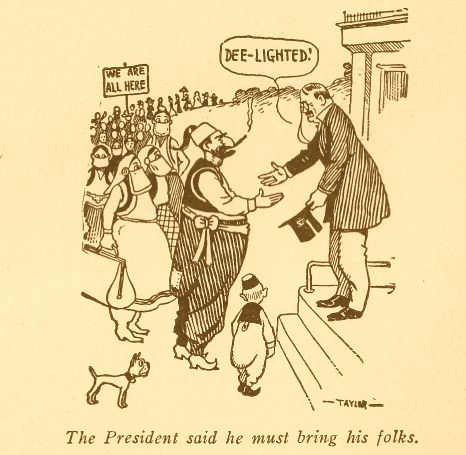

CHAPTER III.

The Bad Boy Writes About the Fun They Had Going to

Washington—He and His Dad Call on President Roosevelt—

The Bad Boy Meets One of the Children and They Disagree.

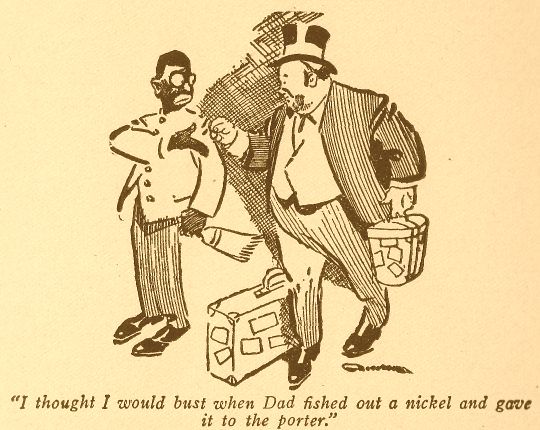

Washington, D. C—My Dear Old Skate: I didn’t tell you in my last about the fun we had getting here. We were on the ocean wave two days, because the whole country was flooded from the rains, and dad walked the quarter deck of the Pullman car, and hitched up his pants, and looked across the sea on each side of the train with a field glass, looking for whales and porpoises. He seems to be impressed with the idea that this trip abroad is one of great significance to the country, and that he is to be a sort of minister plenipotentiary, whatever that is, and that our country is going to be judged by the rest of the world by the position he takes on world affairs. The first day out of Chicago dad corraled the porter in a section and talked to him until the porter was black in the face. I told dad the only way to get respectful consideration from a negro was to advocate lynching and burning at the stake, for the slightest things, so when our porter was unusually attentive to a young woman on the car dad hauled him over the coals, and scared him so by talking of hanging, and burning in kerosene oil, that the negro got whiter than your shirt, and when he got away from dad he came to me and asked if that old man with the red nose and the gold-headed cane was as dangerous as he talked. I told him he was my dad, and that he was a walking delegate of the Amalgamated Association of Negro Lynchers, and when a negro did anything that he ought to be punished for they sent for dad, and he took charge of the proceedings and saw that the negro was hanged, and shot, and burned up plenty. But I told him that dad was crazy on the subject of giving tips to servants, and he must not fall dead when we got to Washington if dad gave him a $50 bill, and he must not give back any change, but just act as though he always got $50 from passengers. Well, you’d a dide to see that negro brush dad 50 times a day, and bring a towel every few minutes to wipe off his shoes, but he kept one eye,’ about as big as an onion, on dad all the time, to watch that he didn’t get stabbed. The next morning I took dad’s pants from under his pillow, and hid them in a linen closet, and dad laid in his berth all the forenoon, and had it out with the porter, whom he accused of stealing them. The doctors told me I must keep dad interested and excited, so he would not dwell on his sickness, and I did, sure as you are a foot high. Dad stood it till almost noon, when he came out of his berth with his pajamas on, these kind with great blue stripes like a fellow in the penitentiary, and when he went to the wash room I found his pants and then he dressed up and swore some at everybody but me. We got to Washington all right, and I thought I would bust when dad fished out a nickel and gave it to the porter, and we got out of the car before the porter came to, and the first day we stayed in the hotel for fear the negro would see us, as I told dad that porter would round up a gang of negroes with razors and they would waylay us and cut dad all up into sausage meat.

Dad is the bravest man I ever saw when there is no danger, but when there is a chance for a row he is weak as a cat. I spect it is on account of his heart being weak. A man’s internal organs are a great study. I spose a brave man, a hero, has to have all his inside things working together, to be real up and up brave, but if his heart is strong, and his liver is white, he goes to pieces in an emergency, and if his liver is all right, and he tries to fight just on his liver, when the supreme moment arrives, and his heart jumps up into his throat, and wabbles and beats too quick, he just flunks. I would like to dissect a real brave man, and see what condition the things inside him are in, but it would be a waste of time to dissect dad, ‘cause I know all his inner works need to go to a watchmaker and be cleaned, and a new main spring put in.

Well, this morning dad shaved himself, and got on his frock coat, and his silk hat, and said we would go over to the white house and have a talk with Teddy, but first he wanted to go and see where Jefferson hitched his horse to the fence when he came to Washington to be innogerated, and where Jackson smoked his corn cob pipe, and swore and stormed around when he was mad, and to walk on the same paths where Zachariah Taylor Zacked, Buchanan catched it, and Lincoln put down the rebellion, and so we walked over toward the white house, and I was scandalized. I stopped to pick up a stone to throw at a dog inside the fence, and when I walked along behind dad, and got a rear view of his silk hat, it seemed as though I would sink through the asphalt pavement, for he had on an old silk hat that he wore before the war, the darnedest looking hat I ever saw, the brim curled like a minstrel show hat, the fur rubbed off in some places, and he looked like one of these actors that you see pictures of walking on the railroad track, when the show busts up at the last town. I think a man ought to dress so his young son won’t have a fit. I tried to get dad to go and buy a new hat, but he said he was going to wait till he got to London, and buy one just like King Edward wears, but he will never get to London with that hat, ‘cause to-night I will throw it out of the hotel window and put a piece of stove pipe in his hat box.

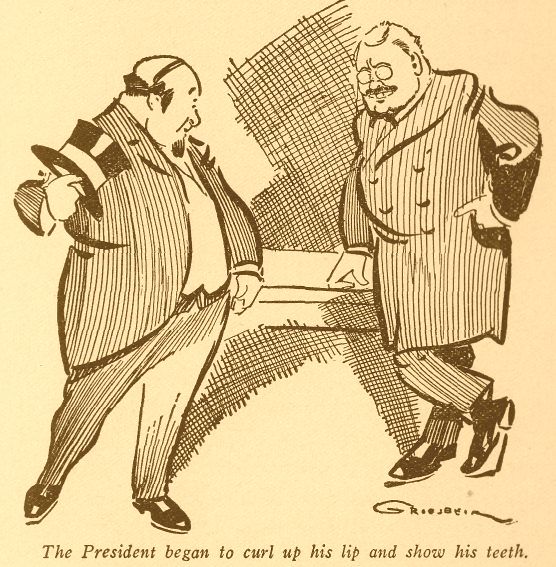

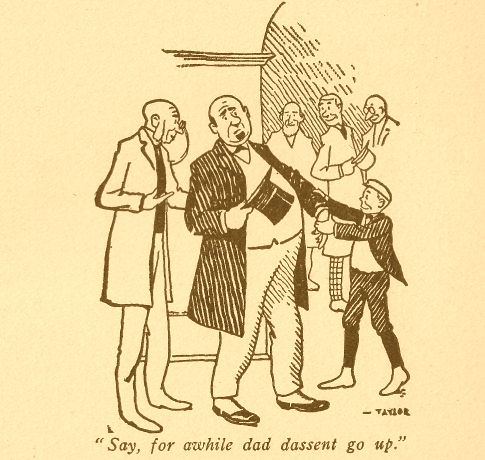

Well, sir, you wouldn’t believe it, but we got into the white house without being pulled, but it was a close shave, ‘cause everybody looked at dad, and put their forefingers to their foreheads, for they thought he was either a crank, or an ambassador from some furrin country. The detectives got around dad when we got into the anteroom, and began to feel of his pockets to see if he had a gun, and one of them asked me what the old fellow wanted, and I told them he was the greatest bob cat shooter in the west, and was on his way to Europe to invite the emperors and things to come over to this country and shoot cats on his preserve. Well, say, you ought to have seen how they stepped one side and waltzed around, and one of them went in the next room and told the president dad was there, and before we knew it we were in the president’s room, and the president began to curl up his lip, and show his teeth like some one had said “rats.”

He got hold of dad’s hand, and dad backed off as though he was afraid of being bitten, and then they sat down and talked about mountain lion and cat shooting, and dad said he had a 22 rifle that he could pick a cat off the back fence with every time, out of his bedroom window, and I began to look around at the pictures. Dad and the president talked about all kinds of shooting, from mudhens to moose, and then dad told the president he was going abroad on account of his liver, and wanted a letter of introduction to some of the kings and emperors, and queens, and jacks, and all the face cards, and the president said he made it a practice not to give any personal letters to his friends, the kings, but that dad could tell any of them that he met that he was an American citizen, and that would take him anywhere in Europe, and then he got up and began to show his teeth at dad again, and dad gave him the grand hailing sign of distress of the Grand Army and backed out, dropped his hat, and in trying to pick it up, he stepped on it, but that made it look better, anyway, and we found ourselves outside the room, and a lot of common people from the country were ready to go in and talk politics and cat shooting.

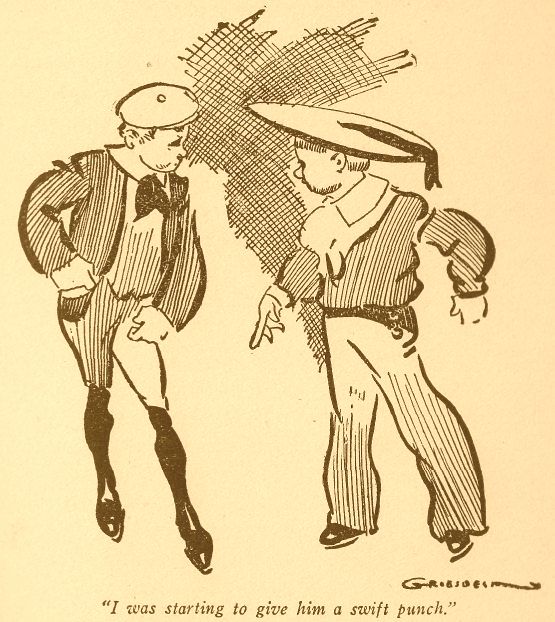

Well, we looked at pictures, and saw the state dining room where they feed 50 diplomats at a time on mud turtle and champagne, and a boy about my size looked sort of disdainful at me, and I told him it he would come outside I would mash his jaw, and he said I could try it right there if I was in a hurry to go, and I was starting to give him a swift punch when a detective took hold of my arm and said they couldn’t have any scrap there, ‘cause the president’s son could not fight with common boys, and I asked him who he called a common boy, and then dad said we better go before war broke out in a country that was illy prepared for hostilities on a large scale, and then I told a detective that dad was liable to have one of his spells and begin shooting any minute, and then the detectives all thought dad was one of these president assassinationists, and they took him into a room and searched him, and asked him a whole lot of fool questions, and they finally let us out, and told us we better skip the town before night.

Dad got kind of heavy-hearted over that and took a notion he would like to see ma again before crossing the briny deep, so you came near having your little angel again soon. This weakness of dad’s didn’t last long, for we’re looking for a warm time in New York and old Lunnon.

So long,

Hennery.

CHAPTER IV.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Visit Mount Vernon—Dad Weeps at the

Grave of the Father of Our Country.

New York City.—My Dear Uncle Ezra: I got a letter from my chum this morning, and he says he was in the grocery the day he wrote, and you were a sight. He says that if I am going to be away several months you will never change your shirt till I get back, for nobody around the grocery seems to have any influence over you. I meant to have put you under bonds before I left, to change your shirt at least quarterly, but you ought to change it by rights every month. The way to do is to get an almanac and make a mark on the figures at the first of the month, and when you are studying the almanac it will remind you of your duty to society. People east here, that is, business men in your class, change their shirts every week or two. Try and look out for these little matters, insignificant as they may seem, because the public has some rights that it is dangerous for a man to ignore.

Dad and I have been down to Mount Vernon, and had a mighty solemn time. I think dad expected that we would be met at the trolley car by a delegation of descendants of George Washington, by a four-horse carriage, with postilions and things, and driven to the old house, and received with some distinction, as dad had always been an admirer of George Washington, and had pointed with pride to his record as a statesman and a soldier, but all we saw was a bunch of negroes, who told us which way to walk, and charged us ten cents apiece for the information.

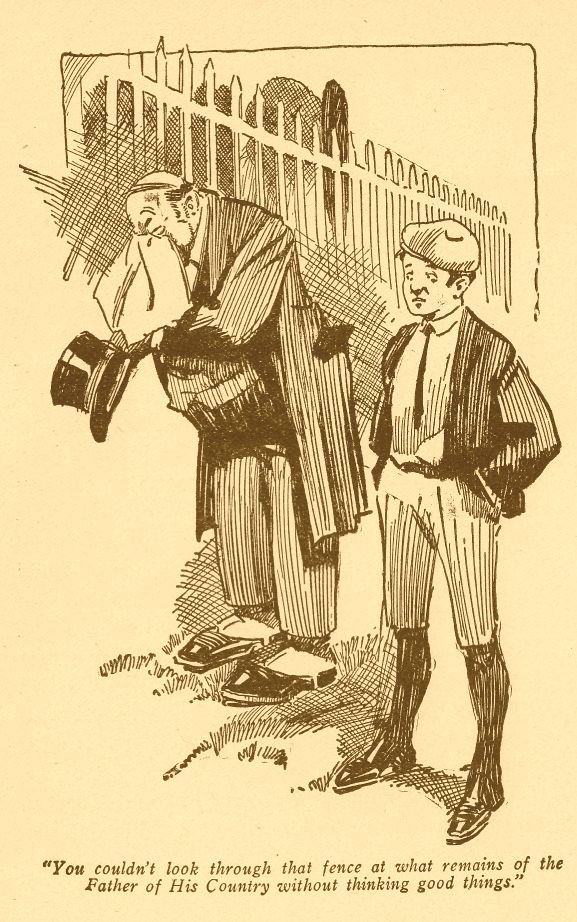

At Mount Vernon we found the old house where George lived and died, where Martha told him to wipe his feet before he came in the house, and saw that things were cooked properly. We saw pictures of revolutionary scenes and men of that period, relics of the days when George was the whole thing around there. We saw the bed on which George died, and then we went down to the icehouse and looked through the fence and saw the marble coffins in which George and Martha were sealed up. Say, old man, I know you haven’t got much reverence, but you couldn’t look through that fence at what remains of the father of his country without taking off your hat and thinking good things while you were there.

I was surprised at dad; he cried, though he never met George Washington in all his life. I have seen dad at funerals at home, when he was a bearer, or a mourner, and he never acted as thought it affected him much, but there at Mount Vernon, standing within eight feet of the remains of George Washington, he just lost his nerve, and bellered, and I felt solemn myself, like I had been kept in after school when all the boys were going in swimming. If a negro had not asked dad for a quarter I know dad would have got down on his knees and been pious, but when he gave that negro a swift kick for butting in with a commercial proposition, in a sacred moment, dad come to, and we went up to the house again. Dad said what he wanted was to think of George Washington just as a country farmer, instead of a general and a president. He said we got nearer to George, if we thought of him getting up in the morning, putting on his old farmer pants and shirt, and going downstairs in his stocking feet, and going out to the kitchen by the wooden bench, dipping a gourd full of rain water out of a barrel into an earthen wash basin and taking some soft soap out of a dish and washing himself, his shirt open so his great hairy breast would catch the breeze, his suspenders, made of striped bed ticking, hanging down, his hair touseled up until he had taken out a yellow pocket comb and combed it, and then yelling to Martha to know about how long a workingman would have to wait for breakfast. And then dad said he liked to think of George Washington sitting down at the breakfast table and spearing sausages out of a platter, and when a servant brought in a mess of these old-fashioned buckwheat cakes, as big as a pieplate, see George, in imagination, pilot a big one on to his plate, and cover it with sausage gravy, and eat like he didn’t have any dyspepsia, and see him help Martha to buckwheat cakes, and finally get up from breakfast like a full Christian and go out on the farm and count up the happy slaves to see if any of them had got away during the night.

By ginger, dad inspired me with new thoughts about the father of his country. I had always thought of Washington as though he was constantly crossing the Delaware in a skiff, through floating ice, with a cocked hat on, and his coat flaps trimmed with buff nankeen stuff, a sort of a male Eliza in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” getting away from the hounds that were chasing her to chew her pants. I was always thinking of George either chopping cherry trees, or standing on a pedestal to have his picture taken, but here at the old farm, with dad to inspire me, I was just mingling with Washington, the planter, the neighbor, telling the negroes where they would get off at if they didn’t pick cotton fast enough, or breaking colts, or going to the churn and drinking a quart of buttermilk, and getting the stomach ache, and calling upstairs to Martha, who was at the spinning wheel, or knitting woolen socks, and asking her to fix up a brandy smash to cure his griping pains. I thought of the father of his country taking a severe cold, and not being able to run into a drug store for a bottle of cough sirup, or a quinine pill, having Martha fix a tub of hot mustard water to soak those great feet of his, and bundle him up in a flannel blanket, give him a hot whisky, and put him to bed with a hot brick at his feet.

Then, when I looked at a duck blind out in the Potomac, near the shore, I thought how George used to put on an old coat and slouch hat and take his gun and go out in the blind, and shoot canvas-back ducks for dinner, and paddle his boat out after the dead birds, the way Grover Cleveland did a century later. I tell you, old man, the way to appreciate our great statesmen, soldiers and scholars is to think of them just as plain, ordinary citizens, doing the things men do nowadays. It does dad and I more good to think of Washington and his friends camping out down the Potomac, on a fishing trip, sleeping on a bed of pine boughs, and cooking their own pork, and roasting sweet potatoes in the ashes, eating with appetites like slaves, than to think of him at a state dinner in the white house, with a French cook disguising the food so they could not tell what it was.

O, I had rather have a picture of George Washington and Lafayette coming up the bank of the Potomac toward the house, loaded down with ducks, and Martha standing on the porch of Mount Vernon asking them who they bought the ducks of and how much they cost, than to have one of those big paintings in the white house showing George and Lafayette looking as though they had conquered the world. If the phonograph had been invented then, and we could listen to the conversation of those men, just as they said things, it would be great. Imagine George saying to Lafayette, so you cotild hear it now: “Lafe, that last shot at that canvasback you made was the longest shot ever made on the Potomac. It was a Jim dandy, you old frog eater,” and imagine Lafayette replying: “You bet your life, George, I nailed that buck canvasback with a charge of number six shot, and he never knew what struck him.” But they didn’t have any phonographs in those days and so you have got to imagine things.

How would Washington’s farewell address sound now in a phonograph, or some of George’s choice swear words at a slave that had ridden a sore-backed mule down to Alexandria after a jug of rum. I would like to run a phonograph show with nothing in the machine but ancient talk from George Washington, but we can have no such luck unless George is born again.

Old man, if you ever get a furlough from business, you go down to Mount Vernon and revel in memories of the father of his country. If you go, hunt up a negro with a hair lip, that is a servant there, and who used to be Washington’s body servant, unless he is a liar, and tell him I sent you and he won’t do a thing to you, for a dollar or so. I told that negro that dad was a great general, a second Washington, and he wore all the skin off his bald head taking off his hat to dad every time dad looked at him, and he bowed until his back ached, but when we were going away, and dad asked me what ailed the old monkey to act that way, the old negro thought these new Washingtons were a pretty tough lot.

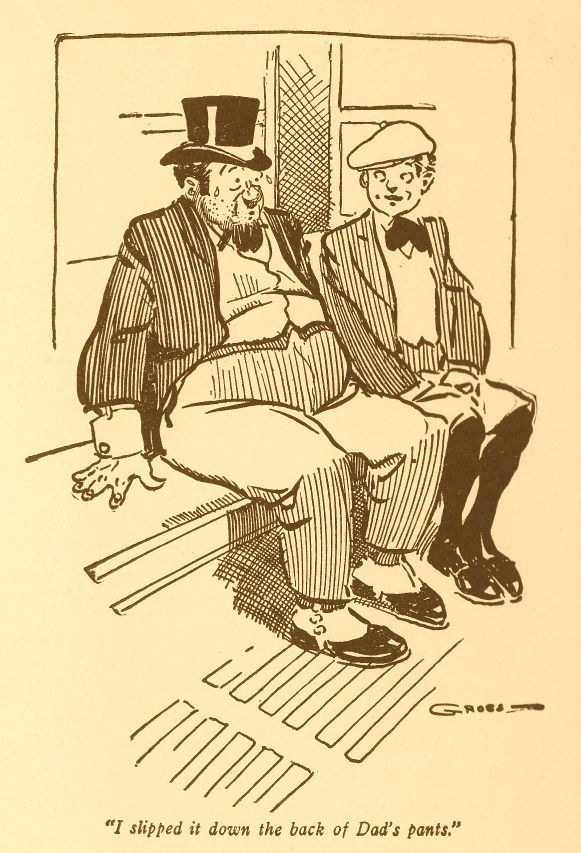

All the time at Mount Vernon I couldn’t get up meanness enough to play any trick on dad, but I picked up a sort of a horse chestnut or something, with prickers on it as sharp as needles, and as we were getting on the trolley I slipped it down the back of dad’s pants, near where his suspenders button on, and by the time we sat down in the car the horse chestnut had worked down where dad is the largest, and when he leaned back against the seat he turned pale and wiggled around and asked me if he looked bad.

I told him he looked like a corpse, which encouraged him so he almost fainted. He asked me if I had heard of any contagious diseases that were prevalent in Virginia, ‘cause he felt as though he had caught something. I told him I would ask the conductor, so I went and asked the conductor what time we got to Washington, and then I went back to dad and told him the conductor said there was no disease of any particular account, except smallpox and yellow fever, and that the first symptom of smallpox was a prickling sensation in the small of the back.

Dad turned green and said he had got it all right, and I had the darndest time getting him back to the hotel at Washington. Say, I had to help him undress, and I took the horse chestnut and put it in the foot of the bed, and got dad in, and I went downstairs to see a doctor, and then I came back and told him the doctor said if the prickly sensation went to his feet he was in no danger from smallpox, as it was an evidence that an old vaccination of years ago had got in its work and knocked the disease out of his system lengthwise, and when I told dad that he raised up in bed and said he was saved, for ever since I went out of the room he had felt that same dreaded prickling at work on his feet, and he was all right.

I told dad it was a narrow escape and that it ought to be a warning to him. Dad has to wear a dress suit to dinner here and cough up money every time he turns around, ‘cause I have told the bell boys dad is a bonanza copper king, and they are not doing a thing to dad.

O, I guess I am doing just as the doctors at home ordered, in keeping dad’s mind occupied.

Well, so long, old man, I have got to go to dinner with dad, and I am going to order the dinner myself, dad said I could, and if I don’t put him into bankruptcy, you don’t know your little

Hennery.

CHAPTER V.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Have Dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria—

The Bad Boy Orders Dinner—The Old Man Gets Stuck—Tries to

Rescue a Countess in Distress.

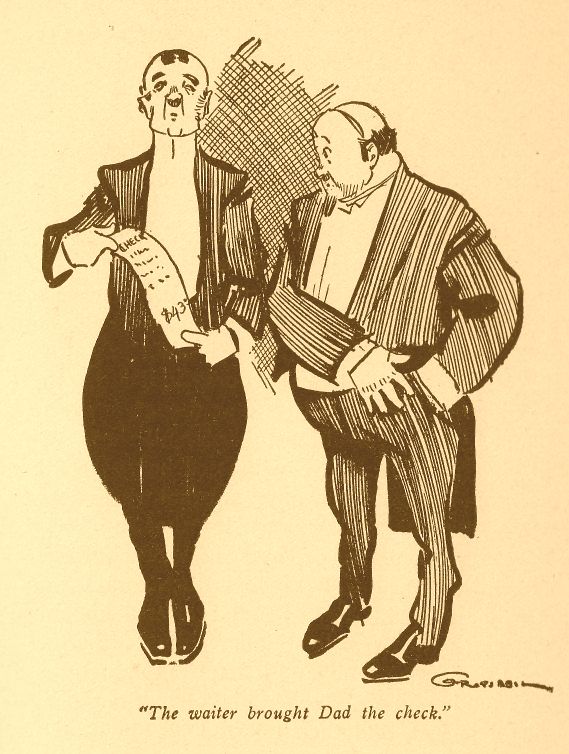

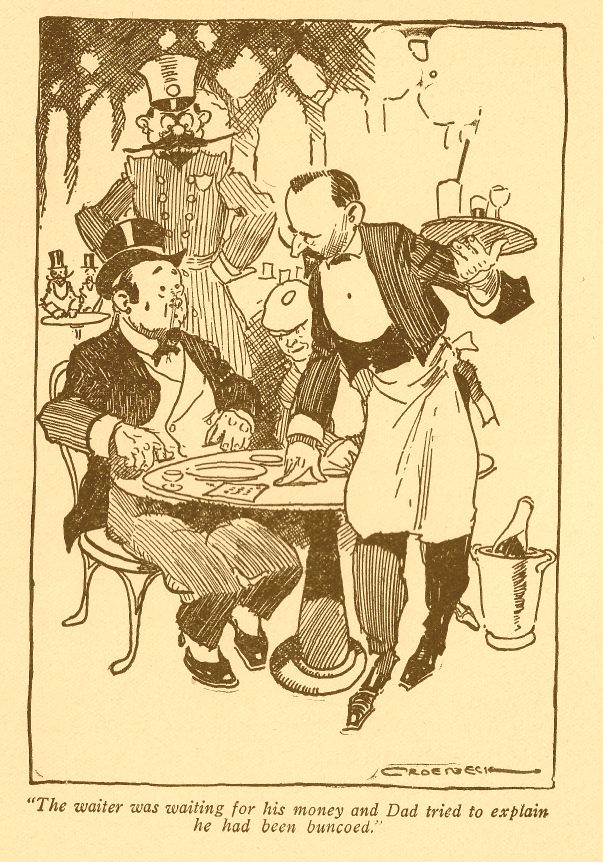

Waldorf-Astoria, New York.—Dear Uncle Ezra: We are still at this tavern, but we don’t do anything but sleep here, and stay around in the lobby evenings to let people look at us, and dad wears that old swallow-tail coat he had before the war, but he has got a new silk hat, since we got here; one of these shiny ones that is so slick it makes his clothes look offul bum. We about went broke on the first supper we had, or dinner they call it here. You see, dad thought this was about a three-dollar-a-day house, and that the meals were included, like they do at Oshkosh, and so when we went down to dinner dad said we wouldn’t do a thing to old Astor. He let me order the dinner, but told me to order everything on the bill-of-sale, because we wanted to get the worth of our three dollars a day. Well, honest, I couldn’t order all there was, ‘cause you couldn’t have got it all on a billiard table. Say, that list they gave me had everything on it that was ever et or drunk, but I told dad they would fire us out if we ordered the whole prescription, so all I ordered was terrapin, canvasback duck, oysters, clams, crabs, a lot of new kinds of fish, and some beef and mutton, and turkey, and woodcock, and partridge, and quail, and English pheasant, and lobster and salads and ices, and pie and things, just to stay our stomachs, and when it came to wine, dad weakened, because he didn’t want to set a bad example to me, so he ordered hard cider for hisself and asked me if I wanted anything to drink, and I ordered brown pop. You’d a been tickled to see the waiter when he took that order, ‘cause I don’t s’pose anybody ever ordered cider and brown pop there since Astor skinned muskrats for a living, when he was a trapper up north. Gosh, but when they brought that dinner in, you ought to have seen the sensation it created. Most of the people in the great dining hall looked at dad as though he was a Crases, or a Rockefeller, and the head waiter bowed low to dad, and dad thought it was Astor, and dad looked dignified and hurt at being spoken to by a common tavern keeper. Well, we et and et, but we couldn’t get away with hardly any of it, and dad wanted to wrap some of the duck and lobsters and things in a newspaper and take it to the room for a lunch, but the waiter wouldn’t have it. But the cyclone struck the house when dad and I got up to go out of the dining-room, and the waiter brought dad the check.

“What is this?” said dad, as he put on his glasses and looked at the check which was $43 and over.

“Dinner check, sir,” said the waiter, as he straightened back and held out his hand.

“Why, ain’t this house run on the American plan?” said dad, as his chin began to tremble.

“No, sir, on the Irish plan,” said the waiter. “You pays for what you horders,” and dad began to dig up. He looked at me as though I was to blame, when he told me to order all there was in sight. Well, I have witnessed heart-rending scenes, but I never saw anything that would draw tears like dad digging down for that $43. The doctors at home had ordered excitement for dad, but this seemed to be an overdose, and I was afraid he would collapse and I offered him my glass of brown pop to stimulate him, but he told me I could go plumb, and if I spoke to him again he would maul me. He got his roll half out of his pistol pocket, and then talked loud and said it was a damoutridge, and he wanted to see Astor himself before he would allow himself to be held up by highwaymen, and then all the other diners stood up and looked at dad, and a lot of waiters and bouncers surrounded him, and then he pulled out the roll, and it was pitiful to see him wet his trembling thumb on his trembling dry tongue and begin to peel off the bills, like you peel the layers off an onion, but he got off enough to pay for the dinner, gave the waiter half a dollar, and smiled a sickly smile at the head waiter, and I led him out of the dining-room a broken-down old man. As we got to the lobby, where the horse show of dress-suit chappies was beginning the evening procession, I said to dad: “Next time we will dine out, I guess,” and at that he rallied and seemed to be able to take a joke, for he said: “We dined out this time. We dined out $43,” and then we joined the procession of walkers around, and tried to look prosperous, and after awhile dad called a bell boy, and asked him if there wasn’t a good dairy lunch counter near the Waldorf, where a man could go and get a bowl of bread and milk, and the bell boy gave him the address of a dairy lunch place, and I can see my finish, ‘cause from this out we will probably live on bread and milk while we are here, and I hate bread and milk.

It got all around the hotel, about the expensive dinner dad ordered for himself and the little heir to his estate, and everybody wanted to get acquainted with dad and try to get some stock in his copper mine. I had told dad about my telling the boys he was a bonanza copper miner, and he never batted an eye when they asked him about his mine, and he looked the part.

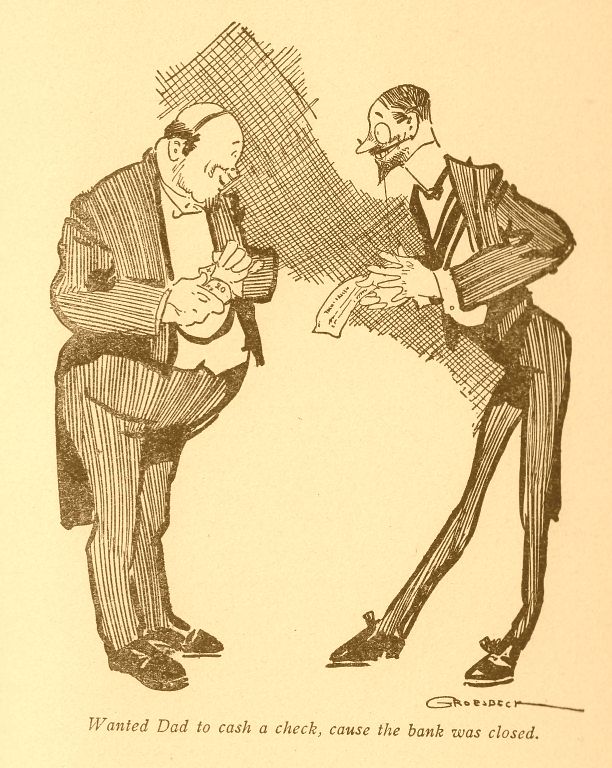

One man wanted dad to cash a check, ‘cause the bank was closed, and he was a rich-looking duke, and dad was just going to get his roll out and peel off some more onion, when I said: “Not on your tintype, Mr. Duke,” and dad left his roll in his pocket, and the duke gave me a look as though he wanted to choke me, and went away, saying: “There is Mr. Pierpont Morgan, and I can get him to cash it.” I saved dad over a hundred dollars on that scheme, and so we are making money every minute. We went to our room early, so dad could digest his $43 worth of glad food.

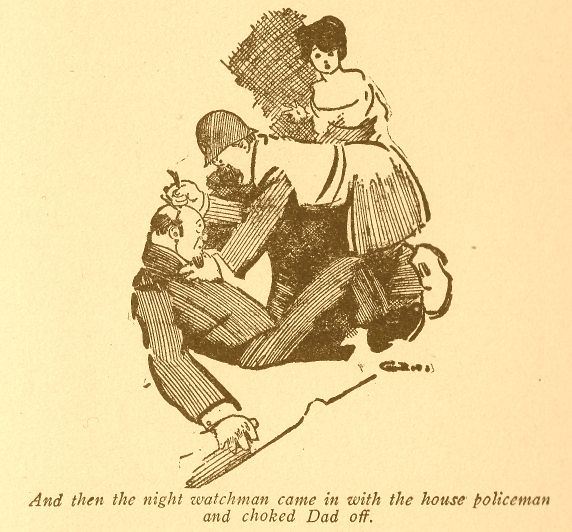

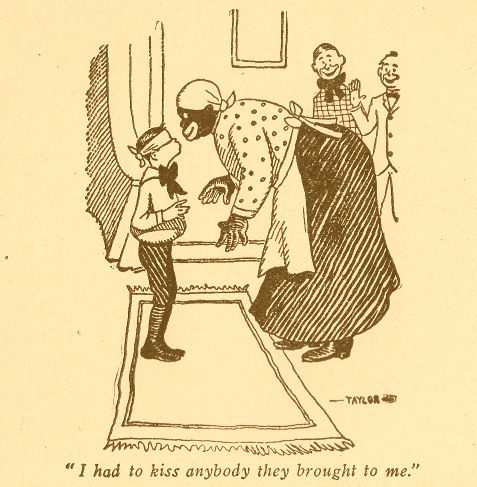

Gee, but this house got ripped up the back before morning. You remember I told you about a countess, or a duchess, or some kind of high-up female that had a room next to our room. Well, she is a beaut, from Butte, Mont., or Cuba, or somewhere, for she acts like a queen that has just stepped off her throne for a good time. She has got a French maid that is a peacharino. You know that horse chestnut, with the prickers on, that I put in dad’s pants at Washington. Well, I have still got it, and as it gets dry the prickers are sharper than needles, sharper even than a servant’s tooth, as it says in the good book. I thought I would give dad a run for his money, ‘cause exercise and excitement are good for a man that dined heartily on $43 worth of rich food, so when we went to our room I told dad that I was satisfied from what a bell boy told me that the countess in the next room, who had gold cords over her shoulders for suspenders, was stuck on him, because she was always inquiring who the lovely old gentleman was with the sweet little boy. Dad he got so interested that he forgot to cuss me about ordering that dinner, and he said he had noticed her, and would like real well to get acquainted with her, ‘cause a man far away from home, sick as a dog, with no loving wife to look after him, needed cheerful company. So I told him I had it all arranged for him to meet her, and then I went out in the hall, sort of whistling around, and the French maid came out and broke some English for me, and we got real chummy, ‘cause she was anxious to learn English, and I wanted to learn some French words; so she invited me into the room, and we sat on the sofa and exchanged words quite awhile, until she was called to the telephone in the other room. Say, you ought to have seen me. I jumped up and put my hand inside the sheets of the bed, and put that chestnut in there, right about the middle of the bed, and then, after learning French quite a spell, with the maid, we heard the countess getting off’ the elevator, and the maid said I must skip, ‘cause it was the countess’ bed-time, and I went back and told dad the whole thing was arranged for him to meet the countess, in a half an hour or so, as she had to write a few letters to some kings and dukes, and when she gave a little scream; as though she was practicing her voice on an opera, or something, dad was to go and rap at the door. Gosh, but I was sorry for dad, for he was so nervous and anxious for the half hour to expire that he walked up and down the room, and looked at himself in the mirror, and acted like he had indigestion. I had told the maid that she and the countess must feel perfectly safe, if anything ever happened, ‘cause my dad was the bravest man in the world, and he would rush to the rescue of the countess, if a burglar got in in the night, or the water pipes busted, or anything, and all she had to do was to screech twice and dad would be on deck, and she must open the door quicker-n scat, and she thanked me, and said she would, and for me to come, too. Say, on the dead, wasn’t that a plot for an amateur to cook up? Well, sir, we had to wait so long for the countess to get on the horse chestnut that I got nervous myself, but after awhile there came a scream that would raise your hair, and I told dad the countess was singing the opera. Dad said: “Hennery, that ain’t no opera, that’s tragedy,” but she gave two or three more stanzas, and I told dad he better hustle, and we went out in the hall and rapped at the door of the countess’ room, and the maid opened it, and told us to send for a doctor and a policeman, ‘cause the countess was having a fit. Well, say, that was the worst ever. The countess had jumped out of bed, and was pulling the lace curtains around her, but dad thought she was crazy, and was going to jump out of the window, and he made a grab for her, and he shouted to her to “be cam, be cam, poor woman, and I will rescue you.” I tried to pacify the maid the best I knew how, and dad was getting the countess calmer, but she evidently thought he was an assassin, for every little while she would yell for help, and then the night watchman came in with a house policeman, and one of them choked dad off, and they asked the countess what the trouble was, and she said she had just retired when she was stabbed about a hundred times in the small of the back with a poniard, and she knew conspirators were assassinating her, and she screamed, and this old bandit, meaning dad, came in, and the little monkey, meaning me, had held his hand over her maid’s mouth, so she could not make any outcry.

Well, I got my horse chestnut all right, out of the bed, and the policeman told the countess not to be alarmed, and go back to bed, and they took dad and I to our room, and asked us all about it. Gee, but dad put up a story about hearing a woman scream in the next room, and, thinking only of the duty of a gentleman under the circumstances, rushed to her rescue, and all there was to it was that she must have had a nightmare, but he said if he had it to do over again, he would do the same. Anyway, the policeman believed dad, and they went off and left us, and we went to bed, but dad said: “Hennery, you understand, I don’t want to make any more female acquaintances, see, among the crowned heads, and from this out we mingle only with men. The idea of me going into a woman’s room and finding a Floradora with fits and tantrums, and me, a sick man. Now, don’t write to your ma about this, ‘cause she never did have much confidence in me, around women with fits.” So, Uncle Ezra, you must not let this get into the papers, see?

Well, we have bought our tickets for Liverpool, and shall sail to-morrow, and while you are making up your cash account Saturday night, we shall be on the ocean. I s’pose I will write you on the boat, if they will tie it up somewhere so it will stand level. Your dear boy. Hennery.

CHAPTER VI.

The Bad Boy Writes the Old Groceryman About Ocean Voyages—

His Dad Has an Argument Over a Steamer Chair.

On Board the Lucinia, Mid-ocean.

Dear Old Geezer.

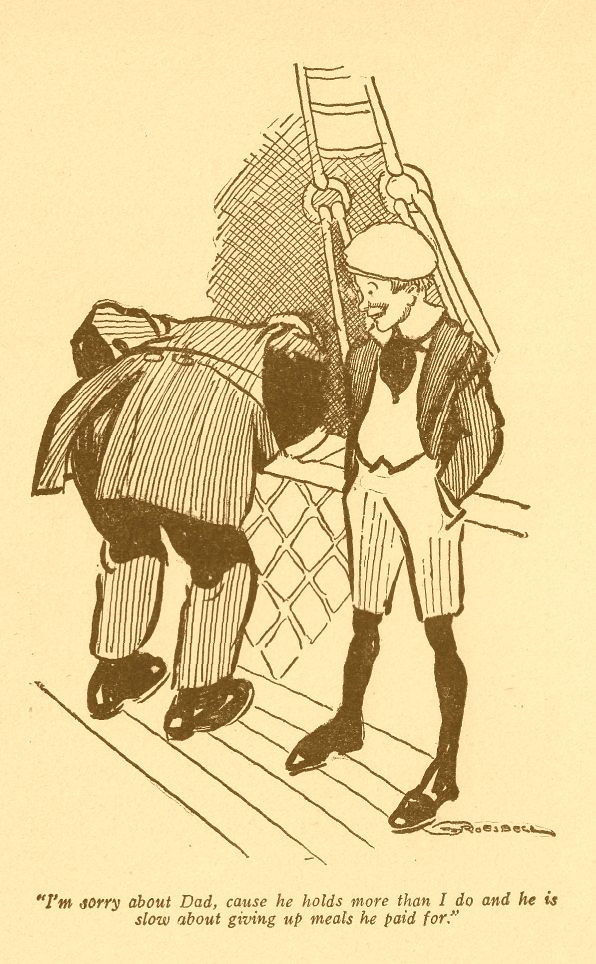

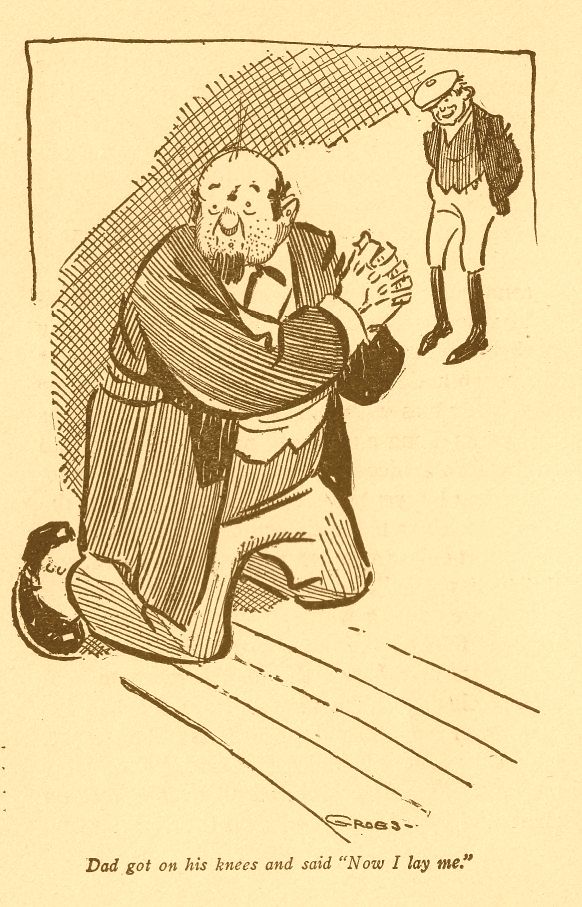

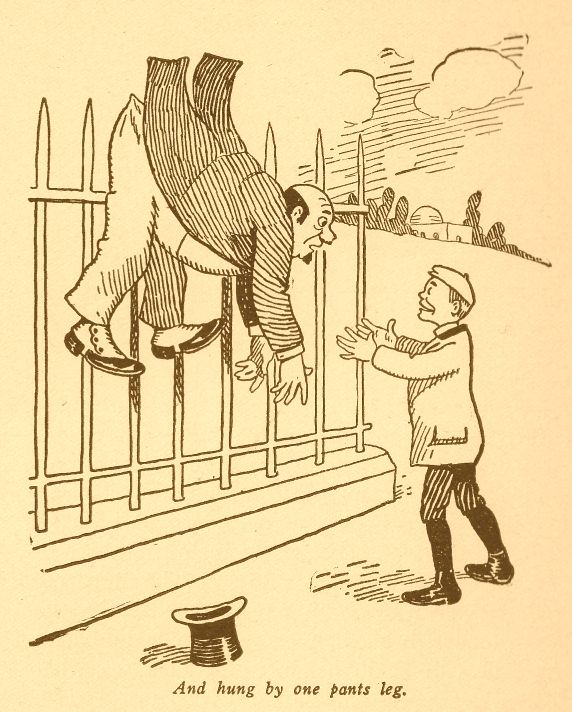

I take the first opportunity, since leaving New York, to write you, ‘cause the boat, after three days out, has got settled down so it runs level, and I can write without wrapping my legs around the table legs, to hold me down. I have tried a dozen times to write, but the sea was so rough that part of the time the table was on top of me and part of the time I was on top, and I was so sick I seem to have lost my mind, over the rail, with the other things supposed to be inside of me. O, old man, you think you know what seasickness is, ‘cause you told me once about crossing Lake Michigan on a peach boat, but lake sickness is easy compared with the ocean malady. I could enjoy common seasickness and think it was a picnic, but this salt water sickness takes the cake. I am sorry for dad, because he holds more than I do, and he is so slow about giving up meals that he has paid for, that it takes him longer to commune with nature, and he groans so, and swears some.

I don’t see how a person can swear when he is seasick on the ocean, with no sure thing that he will ever see land again, and a good prospect of going to the bottom, where you got to die in the arms of a devil fish, with a shark biting pieces out of your tender loin and a smoked halibut waiting around for his share of your corpse, and whales blowing syphons of water and kicking because they are so big that they can’t get at you to chew cuds of human gum, and porpoises combing your damp hair with their fine tooth comb fins, and sword fish and sawtooth piscatorial carpenters sawing off steaks. Gee, but it makes me crawl. I once saw a dead dog in the river, with bull heads and dog-fish ripping him up the back, and I keep thinking I had rather be that dog, in a nice river at home, with bullheads that I knew chewing me at their leisure, than to be a dead boy miles down in the ocean, with strange fish and sea serpents quarreling over the tender pieces in me. A man told me that if you smoke cigarets and get saturated with nickoteen, and you are drownded, the fish will smell of you, and turn up their noses and go away and leave your remains, so I tried a cigaret, and, gosh, but I had rather be et by fish than smoke another, on an ocean steamer. It only added to my sickness, and I had enough before. I prayed some, when the boat stood on its head and piled us all up in the front end, but a chair struck me on the place where Fitzsimmons hit Corbett, and knocked the prayer all out of me, and when the boat stood on her butt end and we all slid back the whole length of the cabin, and I brought up under the piano, I tried to sing a hymn, such as I used to in the ‘Piscopal choir, before my voice changed, but the passengers who were alive yelled for some one to choke me, and I didn’t sing any more. Dad was in the stateroom when we were rolling back and forth in the cabin, and between sicknesses he came out to catch me and take me into the stateroom, but he got the rolling habit, too, and he rolled a match with an actress who was voyaging for her health, and they got offully mixed up. He tried to rescue her, and grabbed hold of her belt and was reeling her in all right, when a man who said he was her husband took dad by the neck and said he must keep his hands off or get another nose put on beside the one he had, and then they all rolled under a sofa, and how it came out I don’t know, but the next morning dad’s eye was blacked, and the fellow who said he was her husband had his front teeth knocked out, and the actress lost her back hair and had to wear a silk handkerchief tied around her head the rest of the trip, and she looked like a hired girl who has been out to a saloon dance.

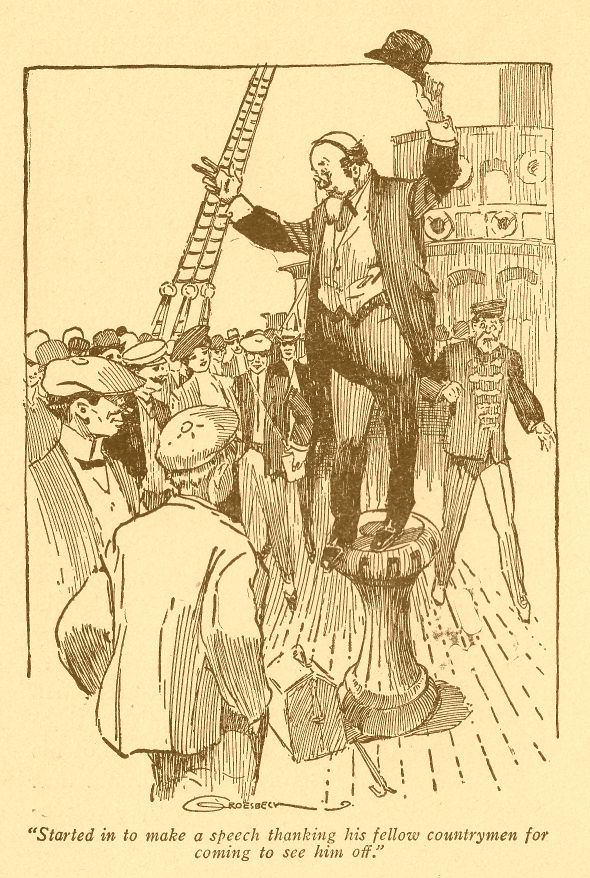

The trouble with dad is that he butts in too much. He thinks he is the whole thing and thinks every crowd he sees is a demonstration for him. When the steamer left New York, there were hundreds of people on the dock to see friends off, and they had flowers to present to Unfriends, and dad thought they were all for him, and he reached for every bunch of roses that was brought aboard, and was going to return thanks for them, when they were jerked away from him, and he looked hurt. When the gang plank was pulled in, and the boat began to wheeze, and grunt, and move away from the dock, and dad saw the crowd waving handkerchiefs and laughing, and saying bon voyage, he thought they were doing it all for him, and he started in to make a speech, thanking his fellow countrymen for coming to see him off, and promising them that he would prove a true representative of his beloved country in his travels abroad, and that he would be true to the stars and stripes wherever fortune might place him, and all that rot, when the boat got so far away they could not hear him, and then he came off his perch, and said, “Hennery, that little impromptu demonstration to your father, on the eve of his departure from his native land, perhaps never to return, ought to be a deep and lasting lesson to you, and to show you that the estimation in which I am held by our people, is worth millions to you, and you can point with pride to your father.” I said “rats” and dad said he wouldn’t wonder if the boat was full of rats, and then we stood on deck, and watched the objects of interest down the bay.

As we passed the statue of Liberty, which France gave to the republic, on Bedloe’s Island, dad started to make a speech to the passengers, but one of the officers of the boat told dad this was no democratic caucus, and that choked him off, but he was loaded for a speech, and I knew it was only a matter of time when he would have to fire it off, but I thought when we got outside the bar, into the ocean, his speech would come up with the rest of the stuff, and I guess it did, for after he began to be sea sick he had to keep his mouth shut, which was a great relief to me, for I felt that he would say something that would get this country in trouble with other nations, as there were lots of foreigners on board. I heard that J. Pierpont Morgan was on board, and I told everybody I got in conversation with that dad was Pierpont Morgan, and when people began to call him Mr. Morgan, I told dad the passengers thought he was Morgan; the great financier, and it tickled dad, and he never denied it. Anyway, the captain put dad and I at his own table, and he called me “Little Pierp,” and everybody discussed great financial questions with dad, and everything would have been lovely the whole trip, only Morgan came amongst us after he had been sea sick for three days, and they gave him a seat opposite us, and with two Morgans at the same table it was a good deal like two Uncle Tom’s in an Uncle Tom’s Cabin show, so dad had to stay in his stateroom on account of sickness, a good deal. Then dad got to walking on deck and flirting with the female passengers. Say, did you ever see an old man who was stuck on hisself, and thought that every woman who looked at him, from curiosity, or because he had a wart on his neck, and watch him get busy making ‘em believe he is a young and kitteny thing, who is irresistible? Gee, but it makes me tired. No man can mash, and make eyes, and have a love scene, when he has to go to the rail every few minutes and hump hisself with something in him that is knocking at the door of his palate, to come out the same way it went in. Dad found a widow woman who looked back at him kind of sassy, when he braced up to her, and when the ship rolled and side-stepped, he took hold of her arm to steady her, and she said maybe they better sit down on deck and talk it over, so dad found a couple of steamer chairs that were not in use, and they sat down near together, and dad took hold of her hand to see if she was nervous, and he told me I could go any play mumbletypeg in the cabin, and I went in the cabin and looked out of the window at dad and the widow. Say, you wouldn’t think two chairs could get so close, and dad was sure love sick, and so was she. The difference between love sick and sea sick is that in love sick you look red in the face and snuggle up, and squeeze hands, and look fondly, and swallow your emotion, and try to wait patiently until it is dark enough so the spectators won’t notice anything, and in sea sickness you get pale in the face, and spread apart, and let go of hands, and after you have stood it as long as you can you rush to the rail and act as though you were going to jump overboard, and then stop sudden and let-’er-go-gallagher, right before folks, and after it is over you try to look as though you had enjoyed it. I will say this much for dad, he and the widow never played a duet over the rail, but they took turns, and dad held her as tenderly as though they were engaged, and when he got her back to the steamer chair he stroked her face and put camphor to her nose, and acted like an undertaker that wasn’t going to let the remains get away from him. They were having a nice convalescent time, just afore it broke up, and hadn’t either of them been sick for ten minutes, and dad had put his arm around her shoulders, and was talking cunning to her, and she was looking lovingly into dad’s eyes, and they were talking of meeting again in France in a few weeks, where she was going to rent a villa, and dad was saying he would be there with both feet, when I opened the window and said, “The steward is bringing around a lunch, and I have ordered two boiled pork sandwiches for you two easy marks.” Well, you’d a dide to see ‘em jump. What there is about the idea of fat pork that makes people who are sea sick have a relapse, I don’t know, but the woman grabbed her stum-mix in both hands and left dad and rushed into the cabin yelling “enough,” or something like that, and dad laid right back in the chair and blatted like a calf, and said he would kill me dead when we got ashore. Just then an Englishman came along and told dad he better get up out of his chair, and dad said whose chair you talking about, and the man said the chair was his, and if dad didn’t get out of it, he would kick him in the pants, and dad said he hadn’t had a good chance at an Englishman since the Revolutionary war, and he just wanted a chance to clean up enough Englishmen for a mess, and dad got up and stood at “attention,” and the Englishman squared off like a prize fighter, and they were just going to fight the battle of Bunker Hill over again, when I run up to an officer with gold lace on his coat and lemon pie on his whiskers, and told him an old crazy Yankee out on deck was going to murder a poor sea sick Englishman, and the officer rushed out and took dad by the coat collar and made him quit, and when he found what the quarrel was about, he told dad all the chairs were private property belonging to the passengers, and for him to keep out of them, and he apologized to the Englishman and they went into the saloon and settled it with high balls, and dad beat the Englishman by drinking two high balls to his one. Then dad set into a poker game, with ten cents ante, and no limit, and they played along for a while until dad got four jacks, and he bet five dollars, and a Frenchman raised him five thousand dollars, and dad laid down his hand and said the game was too rich for his blood, and when he reached in his vest pocket for money to pay for his poker chips he found that his roll was gone, and he said he would leave his watch for security until he could go to his state room and get some money, and then he found that his watch had been pinched, and the Englishman said he would be good for it, and dad came out in the cabin and wanted me to help him find the widow, cause he said when she laid her head on his shoulder, to recover from her sickness, he felt a fumbling around his vest, but he thought it was nothing but his stomach wiggling to get ready for another engagement, but now he knew she had robbed him. Say, dad and I looked all over that boat for the widow, but she simply had evaporated. But land is in sight, and we shall land at Liverpool this afternoon, and dad is going to lay for the widow at the gang plank, and he won’t do a thing to her. I guess not. Well, you will hear from me in London next, and I’ll tell you if dad got his money and watch back.

Hennery.

CHAPTER VII.

The Bad Boy and His Dad Eat Fog—Call on Astor—A Dynamite

Outrage.

London, England.

Dear Old Man:

Well, sir, if a court sentenced me to live in this town, I would appeal the case, and ask the judge to temper his sentence with mercy, and hang me. Say, the fog here is so thick you have to feel around like a blind goddess, and when you show up through the fog you look about eighteen feet high, and you are so wet you want to be run through a clothes wringer every little while. For two days we never left the hotel, but looked out of the windows waiting for the fog to go by, and watching the people swim through it, without turning a hair. Dad was for going right to the Lord Mayor and lodging a complaint, and demanding that the fog be cleared off, so an American citizen could go about town and blow in his money, but I told him he could be arrested for treason. He come mighty near being arrested on the cars from Liverpool to London. When we got off the steamer and tried to find the widow who robbed dad of his watch and roll of money, but never found her, we were about the last passengers to reach the train, and when we got ready to get on we found these English cars that open on the sides, and they put you into a box stall with some other live stock, and lock you in, and once in a while a guard opens the door to see if you are dead from suffocation, or have been murdered by the other passengers. Dad kicked on going in one of the kennels the first thing, and said he wanted a parlor car; but the guard took dad by the pants and gave him a shove, and tossed me in on top of dad, and two other passengers and a woman in the compartment snickered, and dad wanted to fight all of ‘em except the woman, but he concluded to mash her. When the door closed clad told the guard he would walk on his neck when the door opened, and that he was not an entry in a dog show, and he wanted a kennel all to himself, and asked for dog biscuit. Gee, but that guard was mad, and he gave dad a look that started the train going. I whispered to dad to get out his revolver, because the other passengers looked like hold up men, and he took his revolver out of his satchel and put it in his pistol pocket, and looked fierce, and the woman began to act faint, while the passengers seemed to be preparing to jump on dad if he got violent. When the train stopped at the first station I got out and told the guard that the old gentleman in there was from Helena, Montana, and that he had a reputation from St. Paul to Portland, and then I held up both hands the way train robbers make passengers hold up their hands. When I went back in the car dad was talking to the woman about her resembling a woman he used to know in the states, and he was just going to ask her how long she had been so beautiful, when the guard came to the side door and called the woman out into another stall, and then one of the passengers pulled out a pair of handcuffs and told dad he might as well surrender, because he was a Scotland yard detective and had spotted dad as an American embezzler, and if he drew that gun he had in his pocket there would be a dead Yankee in about four minutes. Well, I thought dad had nerve before, but he beat the band, right there. He unbuttoned his overcoat and put his finger on a Grand Army button in his buttonhole, and said, “Gentlemen, I am an American citizen, visiting the crowned heads of the old world, with credentials from the President of the United States, and day after tomorrow I have a date to meet your king, on official business that means much to the future peace of our respective countries. Lay a hand on me and you hang from the yard arm of an American battleship.” Well, sir, I have seen a good many bluffs in my time, but I never saw the equal of that, for the detective turned white, and apologized, and asked dad and I out to luncheon at the next station, and we went and ate all there was, and when the time was up the detective disappeared and dad had to pay for the luncheon, but he kicked all the way to London, and the guard would not listen to his complaints, but told him if he tried to hold up the train he would be thrown out the window and run over by the train. We had the compartment to ourselves the rest of the way to London, except about an hour, when the guard shoved in a farmer who smelled like cows, and dad tried to get in a quarrel with him, about English roast beef coming from America, but the man didn’t have his arguing clothes on, so dad began to find fault with me, and the man told dad to let up on the kid or he would punch his bloody ‘ed off. That settled it, when the man dropped his “h,” dad thought he was one of the nobility, and he got quite chummy with the Englishman, and then we got to London, and dad had a quarrel about his baggage, and after threatening to have a lot of fights he got his trunk on the roof of a cab, and in about an hour we got to the hotel, and then the fog began an engagement. If the fog here ever froze stiff, the town would look like a piece of ice with fish frozen in. Gee, but I would like to have it freeze in front of our hotel, so I could take an ax and go out and chop a frozen girl out, and thaw her till she came to.