« back

PECK’S BAD BOY AND HIS PA.

By Geo. W. Peck

With Illustrations by Gean Smith.

Belford, Clarke & Co. - 1883.

[Transcriber’s Note: The variable grammar and punctuation in

this file make it difficult to decide which errors are

archaic usage and which the printer’s fault. I have made

corrections only of what appeared obvious printer’s errors.

This eBook is taken from the 1883 1st edition.]

A CARD FROM THE AUTHOR.

Office of “Peck’s Sun,” Milwaukee, Feb., 1883.

Belford, Clarke & Co.:

Gents—If you have made up your minds that the world will

cease to move unless these “Bad Boy” articles are given to

the public in book form, why go ahead, and peace to your

ashes. The “Bad Boy” is not a “myth,” though there may be

some stretches of imagination in the articles. The

counterpart of this boy is located in every city, village

and country hamlet throughout the land. He is wide awake,

full of vinegar, and is ready to crawl under the canvas of a

circus or repeat a hundred verses of the New Testament in

Sunday School. He knows where every melon patch in the

neighborhood is located, and at what hours the dog is

chained up. He will tie an oyster can to a dog’s tail to

give the dog exercise, or will fight at the drop of the hat

to protect the smaller boy or a school girl. He gets in his

work everywhere there is a fair prospect of fun, and his

heart is easily touched by an appeal in the right way,

though his coat-tail is oftener touched with a boot than his

heart is by kindness. But he shuffles through life until the

time comes for him to make a mark in the world, and then he

buckles on the harness and goes to the front, and becomes

successful, and then those who said he would bring up in

State Prison, remember that he always was a mighty smart

lad, and they never tire of telling of some of his deviltry

when he was a boy, though they thought he was pretty tough

at the time. This book is respectfully dedicated to boys, to

the men who have been boys themselves, to the girls who like

the boys, and to the mothers, bless them, who like both the

boys and the girls,

Very respectfully,

GEO. W. PECK,

Contents

List of Illustrations

DETAILED CONTENTS:

CHAPTER I.

THE BOY WITH A LAME BACK—THE BOY COULDN’T SIT DOWN—A PRACTICAL JOKE ON

THE OLD MAN—A LETTER FROM “DAISY “—GUARDING THE FOUR CORNERS—THE OLD

MAN IS UNUSUALLY GENEROUS—MA ASKS AWKWARD QUESTIONS—THE BOY TALKED TO

WITH A BED SLAT—NO ENCOURAGEMENT FOR A BOY

CHAPTER II.

THE BOY AT WORK AGAIN—THE BEST BOYS FULL OF TRICKS—THE OLD MAN

LAYS DOWN THE LAW ABOUT JOKES—RUBBER HOSE MACARONI—THE OLD MAS’s

STRUGGLES—CHEWING VIGOROUSLY BUT IN VAIN—AN INQUEST HELD—REVELRY BY

NIGHT—MUSIC IN THE WOODSHED—“‘twas ever thus.”

CHAPTER III.

THE BAD BOY GIVES HIS PA AWAY—PA IS A HARD CITIZEN—DRINKING

SOZODONT—MAKING UP THE SPARE BED—THE MIDNIGHT WAR DANCE—AN

APPOINTMENT BY THE COAL-BIN.

CHAPTER IV.

THE BAD BOY’S FOURTH OF JULY.—PA IS A POINTER, NOT A SETTER—SPECIAL

ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE FOURTH OF JULY—A GRAND SUPPLY OF FIREWORKS—THE

EXPLOSION—THE AIR FULL OF PA AND DOG AND ROCKETS—THE NEW HELL—A SCENE

THAT BEGGARS DESCRIPTION.

CHAPTER V.

THE BAD BOY’S MA COMES HOME.—DEVILTRY, ONLY A LITTLE FUN—THE BAD

BOY’S CHUM—A LADY’S WARDROBE IN THE OLD MAN’S ROOM—MA’s UNEXPECTED

ARRIVAL—WHERE IS THE HUZZY?—DAMFINO!—THE BAD BOY WANTS TO TRAVEL WITH

A CIRCUS

CHAPTER VI.

HIS PA IS A DARN COWARD—HIS PA HAS BEEN A MAJOR—HOW HE WOULD DEAL WITH

BURGLARS—HIS BRAVERY PUT TO THE TEST—THE ICE REVOLVER—HIS PA BEGINS

TO PRAY—TELLS WHERE THE CHANGE IS—“PLEASE MR. BURGLAR SPARE A POOR

MAN’S LIFE!”—MA WAKES UP—THE BAD BOY AND HIS CHUM RUN—FISH-POLE

SAUCE—MA WOULD MAKE A GOOD CHIEF OF POLICE

CHAPTER VII.

HIS PA GETS A BITE.—“HIS PA GETS TOO MUCH WATER”—THE DOCTOR’S

DISAGREE—HOW TO SPOIL BOYS—HIS PA GOES TO PEWAUKEE IN SEARCH OF HIS

SON—ANXIOUS TO FISH—“STOPER, I’VE GOT A WHALE!”—OVERBOARD—HIS PA IS

SAVED—A DOLLAR FOR HIS PANTS.

CHAPTER VIII.

HE IS TOO HEALTHY—AN EMPTY CHAMPAGNE BOTTLE AND A BLACK EYE—HE IS

ARRESTED—OCONOMOWOC FOR HEALTH—HIS PA. IS AN OLD MASHER—DANCED TILL

THE COWS CAME HOME—THE GIRL FROM THE SUNNY SOUTH—THE BAD BOY IS SENT

HOME

CHAPTER IX.

HIS PA HAS GOT ‘EM AGAIN.—HIS PA IS DRINKING HARD—HE HAS BECOME A

TERROR—A JUMPING DOG——THE OLD MAN IS SHAMEFULLY ASSAULTED—“THIS IS

A HELLISH CLIMATE MY BOY!”—HIS PA SWEARS OFF—HIS MA STILL SNEEZING AT

LAKE SUPERIOR

CHAPTER X.

HIS PA HAS GOT RELIGION—THE BAD BOY GOES TO SUNDAY SCHOOL—PROMISES

REFORMATION—THE OLD MAN ON TRIAL FOR SIX MONTHS—WHAT MA THINKS—ANTS

IN PA’S LIVER-PAD—THE OLD MAN IN CHURCH—RELIGION IS ONE THING, ANTS

ANOTHER

CHAPTER XI.

HIS PA TAKES A TRICK—JAMAICA RUM AND CARDS—THE BAD BOY POSSESSED OF

A DEVIL—THE KIND DEACON—AT PRAYER-MEETING—THE OLD MAN TELLS HIS

EXPERIENCE—THE FLYING CARDS—THE PRAYER-MEETING SUDDENLY CLOSED

CHAPTER XII.

HIS PA GETS PULLED—THE OLD MAN STUDIES THE BIBLE—DANIEL IN THE LIONS’

DEN—THE MULE AND THE MULE’S FATHER—MURDER IN THE THIRD WARD—THE OLD

MAN ARRESTED—THE OLD MAN FANS THE DUST OUT OF HIS SON’S PANTS

CHAPTER XIII.

HIS PA GOES TO THE EXPOSITION—THE BAD BOY ACTS AS GUIDE—THE CIRCUS

STORY—THE OLD MAN WANTS TO SIT DOWN—TRIES TO EAT PANCAKES—DRINKS SOME

MINERAL WATER—THE OLD MAN FALLS IN LOVE WITH A WAX WOMAN—A POLICEMAN

INTERFERES—THE LIGHTS GO OUT—THE GROCERY MAN DON’T WANT A CLERK

CHAPTER XIV.

HIS PA CATCHES ON—TWO DAYS AND NIGHTS IN THE BATHROOM—RELIGION CAKES

THE OLD MAN’S BREAST—THE BAD BOY’S CHUM DRESSED UP AS A GIRL—THE OLD

MAN DELUDED—THE COUPLE START FOR THE COURT HOUSE PARK—HIS MA APPEARS

ON THE SCENE—“IF YOU LOVE ME, KISS ME?”—MA TO THE RESCUE—“I AM DEAD

AM I?”—HIS PA THROWS A CHAIR THROUGH THE TRANSOM

CHAPTER XV.

HIS PA AT THE RE-UNION—THE OLD MAN IN MILITARY SPLENDOR—TELLS HOW HE

MOWED DOWN THE REBELS—“I AND GRANT”—WHAT IS A SUTLER.—TEN DOLLARS FOR

PICKLES!—“LET US HANG HIM!”—THE OLD MAN ON THE RUN—HE STANDS UP TO

SUPPER—THE BAD BOY IS TO DIE AT SUNSET

CHAPTER XVI.

THE BAD BOY IN LOVE—ARE YOU A CHRISTIAN?—NO GETTING TO HEAVEN ON SMALL

POTATOES—THE BAD BOY HAS TO CHEW COBS—MA SAYS IT’S GOOD FOR A BOY

TO BE IN LOVE—LOVE WEAKENS THE BAD BOY—HOW MUCH DOES IT COST TO GET

MARRIED?—MAD DOG—NEVER EAT ICE CREAM

CHAPTER XVII.

HIS PA FIGHTS HORNETS—THE OLD MAN LOOKS BAD—THE WOODS OF

WAUWATOSA—THE OLD MAN TAKES A NAP—“HELEN DAMNATION!”—“HELL IS OUT

FOR NOON.”—THE LIVER MEDICINE—ITS WONDERFUL EFFECTS—THE BAD BOY

IS DRUNK—GIVE ME A LEMON!—A SIGHT OF THE COMET!—THE HIRED GIRL’S

RELIGION

CHAPTER XVIII.

HIS PA GOES HUNTING—MUTILATED JAW—THE OLD MAN HAS TAKEN TO SWEARING

AGAIN—OUT WEST, DUCK SHOOTING—-HIS COAT TAIL SHOT OFF—SHOOTS AT A

WILD GOOSE—THE GUN KICKS!—THROWS A CHAIR AT HIS SON—THE ASTONISHED

SHE-DEACON

CHAPTER XIX.

HIS PA IS “NISHIATED”—ARE YOU A MASON?—NO HARM TO PLAY AT LODGE—WHY

GOATS ARE KEPT IN STABLES—THE BAD BOY GETS THE GOAT UPSTAIRS—THE GRAND

DUMPER DEGREE—KYAN PEPPER ON THE GOAT’S BEARD—“BRING FORTH THE ROYAL

BUMPER”—THE GOAT ON THE RAMPAGE

CHAPTER XX.

HIS GIRL GOES BACK ON HIM. THE GROCERY MAN IS AFRAID—BUT THE BAD BOY IS

A WRECK—“MY GIRL, HAS SHOOK ME!”—THE BAD BOY’S HEART IS BROKEN—STILL

HE ENJOYS A BIT OF FUN—COD LIVER OIL ON THE PANCAKES—THE HIRED GIRLS

MADE VICTIMS—THE BAD BOY VOWS VENGEANCE ON HIS GIRL AND THE TELEGRAPH

MESSENGER

CHAPTER XXI.

HE AND HIS PA IN CHICAGO—NOTHING LIKE TRAVELING TO GIVE TONE—LAUGHING

IN THE WRONG PLACE—A DIABOLICAL PLOT—-HIS PA ARRESTED AS A

KIDNAPPER—-THE NUMBERS ON THE DOORS CHANGED—THE WRONG ROOM—“NOTHIN’

THE MAZZER WITH ME, PET!”—THE TELL-TALE HAT

CHAPTER XXII.

HIS PA IS DISCOURAGED—“I AIN’T NO JONER!”—THE STORY OF THE ANCIENT

PROPHET—THE SUNDAY SCHOOL FOLKS GO BACK ON THE BAD BOY:—CAGED

CATS—A COMMITTEE MEETING—A REMARKABLE CATASTROPHE!—“THAT BOY BEATS

HELL!”—BASTING THE BAD BOY—THE HOT WATER IN THE SPONGE TRICK

CHAPTER XXIII.

HE BECOMES A DRUGGIST—“I HAVE GONE INTO BUSINESS!”—-A NEW

ROSE-GERANIUM PERFUME—-THE BAD BOY IN A DRUGGIST’S STORE—PRACTICING

ON HIS PA—THE EXPLOSION—THE SEIDLETZ POWDER—HIS PA’S FREQUENT

PAINS—POUNDING INDIA-RUBBER—CURING A WART

CHAPTER XXIV. HE QUITS THE DRUG BUSINESS.

HE HAS DISSOLVED WITH THE DRUGGER—THE OLD LADY AND THE GIN—THE BAD BOY

IGNOMINIOUSLY FIRED—HOW HE DOSED HIS PA’S BRANDY—THE BAD BOY AS “HAWTY

AS A DOOK!”—HE GETS EVEN WITH HIS GIRL—-THE BAD BOY WANTS A QUIET

PLACE—THE OLD MAN THREATENS THE PARSON

CHAPTER XXV.

HIS PA KILLS HIM—A GENIUS AT WHISTLING—A FUR-LINED CLOAK A CURE CURE

FOR CONSUMPTION—ANOTHER LETTER SENT TO THE OLD MAN—HE RESOLVES ON

IMMEDIATE PUNISHMENT—THE BLADDER-BUFFER—THE EXPLOSION—A TRAGIC

SCENE—HIS PA VOWS TO REFORM

CHAPTER XXVI.

HIS PA MORTIFIED—SEARCHING FOR SEWER GAS—THE POWERFUL ODOR OF

LIMBURGER CHEESE AT CHURCH—THE AFTER MEETING—FUMIGATING THE HOUSE—THE

BAD BOY RESOLVES TO BOARD AT AN HOTEL.

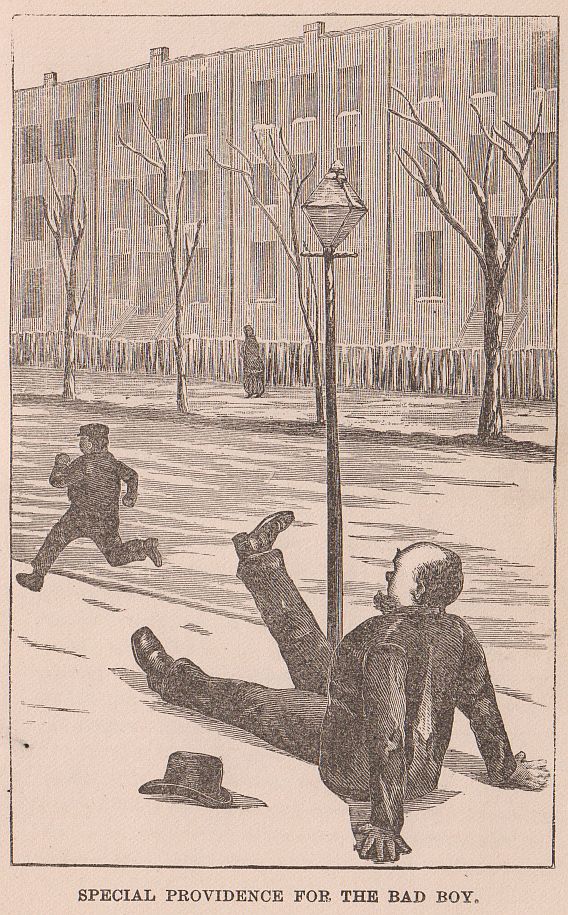

CHAPTER XXVII.

HIS PA BROKE UP—THE BAD BOY DON’T THINK THE GROCER FIT FOR HEAVEN—HE

IS VERY SEVERE ON HIS OLD FRIEND—THE NEED OF A NEW REVISED EDITION—THE

BAD BOY TURNS REVISER—HIS PA REACHES FOR THE POKER—A SPECIAL

PROVIDENCE—THE SLED SLEWED!—HIS PA UNDER THE MULES

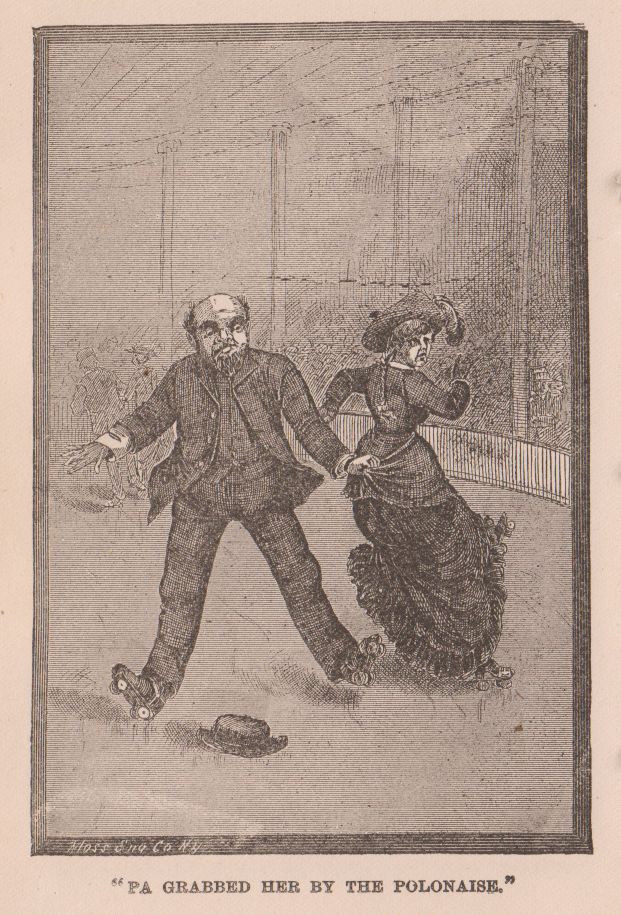

CHAPTER XXVIII.

HIS PA GOES SKATING—THE BAD BOY CARVES A TURKEY—HIS PA’S FAME AS A

SKATER—THE OLD MAN ESSAYS TO SKATE ON ROLLERS—HIS WILD CAPERS—HE

SPREADS HIMSELF—-HOLIDAYS A CONDEMNED NUISANCER—THE BAD BOY’S

CHRISTMAS PRESENTS

CHAPTER XXIX.

HIS PA GOES CALLING—HIS PA STARTS FORTH—A PICTURE OF THE OLD

MAN “FULL”—POLITENESS AT A WINTER PICNIC—ASSAULTED BY

SANDBAGGERS—RESOLVED TO DRINK NO MORE COFFEE—A GIRL FULL OF “AIG NOGG”

CHAPTER XXX.

HIS PA DISSECTED—THE MISERIES OF THE MUMPS—NO PICKLES, THANK

YOU—ONE MORE EFFORT To REFORM THE OLD MAN—THE BAD BOY PLAYS MEDICAL

STUDENT—PROCEEDS TO DISSECT HIS PA—“GENTLEMEN, I AM NOT DEAD!”—SAVED

FROM THE SCALPEL—“NO MORE WHISKY FOR YOU.”

CHAPTER XXXI.

HIS PA JOINS A TEMPERANCE SOCIETY—THE GROCERY MAN SYMPATHISES WITH THE

OLD MAN—WARNS THE BAD BOY THAT HE MAY HAVE A STEP-FATHER!—THE BAD

BOY SCORNS THE IDEA—INTRODUCES HIS PA TO THE GRAND “WORTHY DUKE!”—THE

SOLEMN OATH—THE BRAND PLUCKED FROM THE BURNING

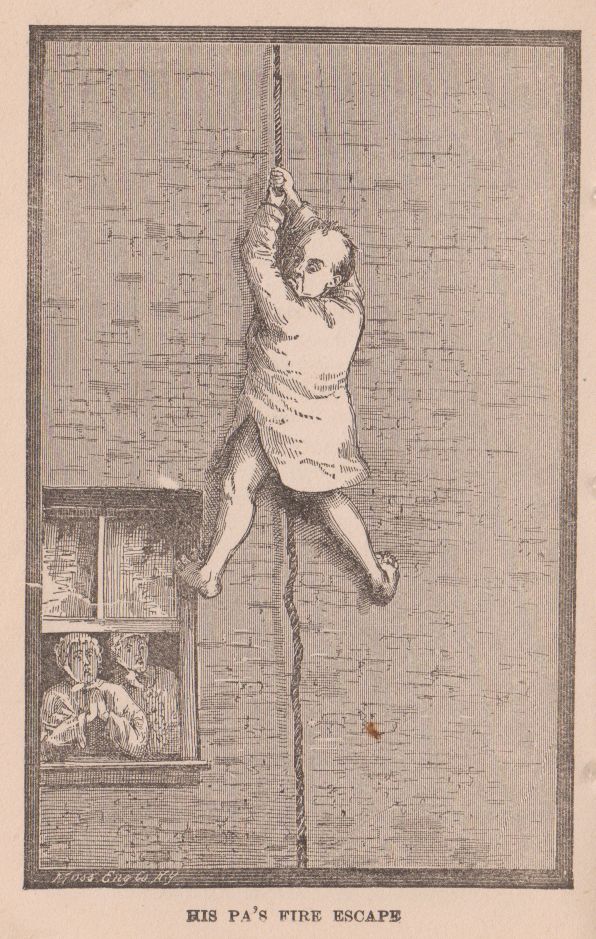

CHAPTER XXXII.

HIS PA’S MARVELOUS ESCAPE—THE GROCERY MAN HAS NO VASELINE—THE OLD

MAN PROVIDES THREE FIRE ESCAPES—ONE OF THE ESCAPES TESTED—HIS PA

SCANDALIZES THE CHURCH—“SHE’S A DARLING!”—WORLDLY MUSIC IN THE COURTS

OF ZION

CHAPTER XXXIII.

HIS PA JOKES HIM—THE BAD BOY CAUGHT AT LAST—HOW TO GROW A

MOUSTACHE—TAR AND CAYENNE PEPPER—THE GROCERY MAN’S FATE IS

SEALED—FATHER AND SON JOIN IN A PRACTICAL JOKE—SOFT SOAP ON THE

STEPS—DOWNFALL OF MINISTERS AND DEACONS—“MA TO THE RESCUE!”—THE BAD

BOY GETS EVEN WITH HIS PA

CHAPTER XXXIV.

HIS PA GETS MAD—A ROOM IN COURT-PLASTER—THE BAD BOY DECLINES BEING

MAULED!—THE OLD MAN GETS A HOT BOX—THE BAD BOY BORROWS A CAT!—THE

BATTLE!—“HELEN BLAZES!”—THE CAT VICTORIOUS!—THE BAD BOY DRAWS THE

LINE AT KINDLING WOOD!

CHAPTER XXXV.

HIS PA AN INVENTOR—THE BAD BOY A MARTYR—THE DOG-COLLAR IN

THE SAUSAGE—A PATENT STOVE—THE PATENT TESTED!—HIS PA A BURNT

OFFERING—EARLY BREAKFAST!

HIS PA GETS BOXED—PARROT FOR SALE—THE OLD MAN IS DOWN ON THE

GROCER—“A CONTRITE HEART BEATS A BOB-TAILED FLUSH!”—POLLY’S

RESPONSES—CAN A PARROT GO TO HELL?—THE OLD MAN GETS ANOTHER BLACK

EYE—DUFFY HITS FOR KEEPS!—NOTHING LIKE AN OYSTER FOR A BLACK EYE

PECK’S BAD BOY.

CHAPTER I.

THE BOY WITH A LAME BACK—THE BOY COULDN’T SIT DOWN—A

PRACTICAL JOKE ON THE OLD MAN—A LETTER FROM “DAISY”—

GUARDING THE FOUR CORNERS—THE OLD MAN IS UNUSUALLY

GENEROUS—MA ASKS AWKWARD QUESTIONS—THE BOY TALKED TO WITH

A BED-SLAT—NO ENCOURAGEMENT FOR A BOY!

A young fellow who is pretty smart on general principles, and who is always in good humor, went into a store the other morning limping and seemed to be broke up generally. The proprietor asked him if he wouldn’t sit down, and he said he couldn’t very well, as his back was lame. He seemed discouraged, and the proprietor asked him what was the matter. “Well,” says he, as he put his hand on his pistol pocket and groaned, “There is no encouragement for a boy to have any fun nowadays. If a boy tries to play an innocent joke he gets kicked all over the house.” The store keeper asked him what had happened to disturb his hilarity. He said he had played a joke on his father and had been limping ever since.

“You see, I thought the old man was a little spry. You know he is no spring chicken yourself; and though his eyes are not what they used to be, yet he can see a pretty girl further than I can. The other day I wrote a note in a fine hand and addressed it to him, asking him to meet me on the corner of Wisconsin and Milwaukee streets, at 7:30 on Saturday evening, and signed the name of ‘Daisy’ to it. At supper time Pa he was all shaved up and had his hair plastered over the bald spot, and he got on some clean cuffs, and said he was going to the Consistory to initiate some candidates from the country, and he might not be in till late. He didn’t eat much supper, and hurried off with my umbrella. I winked at Ma but didn’t say anything. At 7:30 I went down town and he was standing there by the post-office corner, in a dark place. I went by him and said, “Hello, Pa, what are you doing there?” He said he was waiting for a man. I went down street and pretty soon I went up on the other corner by Chapman’s and he was standing there. You see, he didn’t know what corner “Daisy” was going to be on, and had to cover all four corners. I saluted him and asked him if he hadn’t found his man yet, and he said no, the man was a little late. It is a mean boy that won’t speak to his Pa when he sees him standing on a corner, I went up street and I saw Pa cross over by the drug store in a sort of a hurry, and I could see a girl going by with a water-proof on, but she skited right along and Pa looked kind of solemn, the way he does when I ask him for new clothes. I turned and came back and he was standing there in the doorway, and I said, “Pa you will catch cold if you stand around waiting for a man. You go down to the Consistory and let me lay for the man.” Pa said, “never you mind, you go about your business and I will attend to the man.”

“Well, when a boy’s Pa tells him to never you mind, and looks spunky, my experience is that a boy wants to go right away from there, and I went down street. I thought I would cross over and go up the other side, and see how long he would stay. There was a girl or two going up ahead of me, and I see a man hurrying across from the drug store to Van Pelt’s corner. It was Pa, and as the girls went along and never looked around Pa looked mad and stepped into the doorway. It was about eight o’clock then, and Pa was tired, and I felt sorry for him and I went up to him and asked him for half a dollar to go to the Academy. I never knew him to shell out so freely and so quick. He gave me a dollar, and I told him I would go and get it changed and bring him back the half a dollar, but he said I needn’t mind the change. It is awful mean of a boy that has always been treated well to play it on his Pa that way, and I felt ashamed. As I turned the corner and saw him standing there shivering, waiting for the man, my conscience troubled me, and I told a policeman to go and tell Pa that “Daisy” had been suddenly taken with worms, and would not be there that evening. I peeked around the corner and Pa and the policeman went off to get a drink. I was glad they did cause Pa needed it, after standing around so long. Well, when I went home the joke was so good I told Ma about it, and she was mad. I guess she was mad at me for treating Pa that way. I heard Pa come home about eleven o’clock, and Ma was real kind to him. She told him to warm his feet, cause they were just like chunks of ice. Then she asked him how many they initiated in the Consistory, and he said six, and then she asked him if they initiated “Daisy” in the Consistory, and pretty soon I heard Pa snoring. In the morning he took me into the basement, and gave me the hardest talking to that I over had, with a bed slat. He said he knew that I wrote, that note all the time, and he thought he would pretend that he was looking for “Daisy,” just to fool me. It don’t look reasonable that a man would catch epizootic and rheumatism just to fool his boy, does it? What did he give me the dollar for? Ma and Pa don’t seem to call each other pet any more, and as for me, they both look at me as though I was a hard citizen. I am going to Missouri to take Jesse James’s place. There is no encouragement for a boy here. Well, good morning. If Pa comes in here asking for me tell him that you saw an express wagon going to the morgue with the remains of a pretty boy who acted as though he died from concussion of a bed slat on Peck’s bad boy on the pistol pocket. That will make Pa feel sorry. O, he has got the awfulest cold, though.” And the boy limped out to separate a couple of dogs that were fighting.

CHAPTER II.

THE BAD BOY AT WORK AGAIN—THE BEST BOYS FULL OF TRICKS—THE

OLD MAN LAYS DOWN THE LAW ABOUT JOKES—RUBBER-HOSE MACARONI—

THE OLD MAN’S STRUGGLES—CHEWING VIGOROUSLY BUT IN VAIN—AN

INQUEST HELD—REVELRY BY NIGHT—MUSIC IN THE WOODSHED—

“‘TWAS EVER THUS.”

Of course all boys are not full of tricks, but the best of them are. That is, those who are the readiest to play innocent jokes, and who are continually looking for chances to make Rome howl, are the most apt to turn out to be first-class business men. There is a boy in the Seventh Ward who is so full of fun that sometimes it makes him ache. He is the same boy who not long since wrote a note to his father and signed the name “Daisy” to it, and got the old man to stand on a corner for two hours waiting for the girl. After that scrape the old man told the boy that he had no objection to innocent jokes, such as would not bring reproach upon him, and as long as the boy confined himself to jokes that would simply cause pleasant laughter, and not cause the finger of scorn to be pointed at a parent, he would be the last one to kick. So the boy has been for three weeks trying to think of some innocent joke to play on his father. The old man is getting a little near sighted, and his teeth are not as good as they used to be, but the old man will not admit it. Nothing that anybody can say can make him own up that his eyesight is failing, or that his teeth are poor, and he would bet a hundred dollars that he could see as far as ever. The boy knew the failing, and made up his mind to demonstrate to the old man that he was rapidly getting off his base.. The old person is very fond of macaroni, and eats it about three times a week. The other day the boy was in a drug store and noticed in a show case a lot of small rubber hose, about the size of sticks of macaroni, such as is used on nursing bottles, and other rubber utensils. It was white and nice, and the boy’s mind was made up at once. He bought a yard of it, and took it home. When the macaroni was cooked and ready to be served, he hired the table girl to help him play it on the old man. They took a pair of shears and cut the rubber hose in pieces about the same length as the pieces of boiled macaroni, and put them in a saucer with a little macaroni over the rubber pipes, and placed the dish at the old man’s plate. Well, we suppose if ten thousand people could have had reserved seats and seen the old man struggle with the India rubber macaroni, and have seen the boy’s struggle to keep from laughing, they would have had more fun than they would at a circus, First the old delegate attempted to cut the macaroni into small pieces, and failing, he remarked that it was not cooked enough. The boy said his macaroni was cooked too tender, and that his father’s teeth were so poor that he would have to eat soup entirely pretty soon. The old man said, “Never you mind my teeth, young man,” and decided that he would not complain of anything again. He took up a couple of pieces of rubber and one piece of macaroni on a fork and put them in his mouth. The macaroni dissolved easy enough, and went down perfectly easy, but the flat macaroni was too much for him. He chewed on it for a minute or two, and talked about the weather in order that none of the family should see that he was in trouble, and when he found the macaroni would not down, he called their attention to something out of the window and took the rubber slyly from his mouth, and laid it under the edge of his plate. He was more than half convinced that his teeth were played out, but went on eating something else for a while, and finally he thought he would just chance the macaroni once more for luck, and he mowed away another fork full in his mouth. It was the same old story. He chewed like a seminary girl chewing gum, and his eyes stuck out and his face became red, and his wife looked at him as though afraid he was going to die of apoplexy, and finally the servant girl burst out laughing, and went out of the room with her apron stuffed in her mouth, and the boy felt as though it was unhealthy to tarry too long at the table and he went out.

Left alone with his wife the old man took the rubber macaroni from his mouth and laid it on his plate, and he and his wife held an inquest over it. The wife tried to spear it with a fork, but couldn’t make any impression on it, and then she see it was rubber hose, and told the old man. He was mad and glad, at the same time; glad because he had found that his teeth where not to blame, and mad because the grocer had sold him boarding house macaroni. Then the girl came in and was put on the confessional, and told all, and presently there was a sound of revelry by night, in the wood shed, and the still, small voice was saying, “O, Pa, don’t! you said you didn’t care for innocent jokes. Oh!” And then the old man, between the strokes of the piece of clap-board would say, “Feed your father a hose cart next, won’t ye. Be firing car springs and clothes wringers down me next, eh? Put some gravy on a rubber overcoat, probably, and serve it to me for salad. Try a piece of overshoe, with a bone in it, for my beefsteak, likely. Give your poor old father a slice of rubber bib in place of tripe to-morrow, I expect. Boil me a rubber water bag for apple dumplings, pretty soon, if I don’t look out. There! You go and split the kindling wood.” ‘Twas ever thus. A boy cant have any fun now days.

CHAPTER III.

THE BAD BOY GIVES HIS PA AWAY—PA IS A HARD CITIZEN—

DRINKING SOZODONT—MAKING UP THE SPARE BED—THE MIDNIGHT

WAR-DANCE—AN APPOINTMENT BY THE COAL BIN.

The bad boy’s mother was out of town for a week, and when she came home she found everything topsy turvey. The beds were all mussed up, and there was not a thing hung up anywhere. She called the bad boy and asked him what in the deuce had been going on, and he made it pleasant for his Pa about as follows:

“Well, Ma, I know I will get killed, but I shall die like a man. When Pa met you at the depot he looked too innocent for any kind of use, but he’s a hard citizen, and don’t you forget it. He hasn’t been home a single night till after eleven o’clock, and he was tired every night, and he had somebody come home with him.”

“O, heavens, Hennery,” said the mother, with a sigh, “are you sure about this?”

“Sure!” says the bad boy, “I was on to the whole racket. The first night they came home awful tickled, and I guess they drank some of your Sozodont, cause they seemed to foam at the mouth. Pa wanted to put his friend in the spare bed, but there were no sheets on it, and he went to rumaging around in the drawers for sheets. He got out all the towels and table-cloths, and, made up the bed with table-cloths, the first night, and in the morning the visitor kicked because there was a big coffee stain on the table-cloth sheet. You know that tablecloth you spilled the coffee on last spring, when Pa scared you by having his whiskers cut off. O, they raised thunder around the room. Pa took your night-shirt, you know the one with the lace work all down the front, and put a pillow in it, and set it on a chair, then took a burned match and marked eyes and nose on the pillow, and put your bonnet on it, and then they had a war dance. Pa hurt the bald spot on his head by hitting it against the gas chandelier, and then he said dammit. Then they throwed pillows at each other. Pa’s friend didn’t have any night shirt, and Pa gave his friend one of your’n, and the friend took that old hoop-skirt in the closet, the one Pa always steps on when he goes in the close, after a towel and hurts his bare foot, you know, and put it on under the night shirt, and they walked around arm in arm. O, it made me tired to see a man Pa’s age act so like a darn fool.”

“Hennery,” says the mother, with a deep meaning in her voice, “I want to ask you one question. Did your Pa’s friend wear a dress?”

“O, yes,” said the bad boy, coolly, not noticing the pale face of his Ma, “the friend put on that old blue dress of yours, with the pistol pocket in front, you know, and pinned a red cloth on for a train, and they danced the can-can.”

Just at this point Pa came home to dinner, and the bad boy said, “Pa, I was just telling Ma what a nice time you had that first night she went away, with the pillows, and—”

“Hennery!” says the old gentleman severely, “you are a confounded fool.”

“Izick,” said the wife more severely, “Why did you bring a female home with you that night. Have you got no—”

“O, Ma,” says the bad boy, “it was not a woman. It was young Mr. Brown, Pa’s clerk at the store, you know.”

“O!” said Mas with a smile and a sigh.

“Hennery,” said his stern parent, “I want to see you there by the coal bin for a minute or two. You are the gaul durndest fool I ever see. What you want to learn the first thing you do is to keep your mouth shut,” and then they went on with the frugal meal, while Hennery seemed to feel as though something was coming.

CHAPTER IV.

THE BAD BOY’S FOURTH OF JULY—PA IS A POINTER NOT A SETTER—

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE FOURTH OF JULY—A GRAND SUPPLY

OF FIRE WORKS—THE EXPLOSION—THE AIR FULL OF PA AND DOG AND

ROCKETS—THE NEW HELL—A SCENE THAT BEGGARS DESCRIPTION.

“How long do you think it will be before your father will be able to come down to the office?” asked the druggist of the bad boy as he was buying some arnica and court plaster.

“O, the doc. says he could come down now if he would on some street where there were no horses to scare,” said the boy as he bought some gum, “but he says he aint in no hurry to come down till his hair grows out, and he gets some new clothes made. Say, do you wet this court plaster and stick it on?”

The druggist told him how the court plaster worked, and then asked him if his Pa couldn’t ride down town.

“Ride down? well, I guess nix. He would have to set down if he rode down town, and Pa is no setter this trip, he is a pointer. That’s where the pinwheel struck him.”

“Well how did it all happen?” asked the druggist, as he wrapped a yellow paper over the bottle of arnica, and twisted the ends, and then helped the boy stick the strip of court plaster on his nose.

“Nobody knows how it happened but Pa, and when I come near to ask him about it he feels around his night shirt where his pistol pocket would be if it was pants he had on, and tells me to leave his sight forever, and I leave too, quick. You see he is afraid I will get hurt every 4th of July, and he told me if I wouldn’t fire a fire-cracker all day he would let me get four dollars’ worth of nice fire-works and he would fire them off for me in the evening in the back yard. I promised, and he gave me the money and I bought a dandy lot of fire-works, and don’t you forget it. I had a lot of rockets and Roman candles, and six pin-wheels, and a lot of nigger chasers, and some of these cannon fire-crackers, and torpedoes, and a box of parlor matches. I took them home and put the package in our big stuffed chair and put a newspaper over them.

“Pa always takes a nap in that stuffed chair after dinner, and he went into the sitting room and I heard him driving our poodle dog out of the chair, and heard him ask the dog what he was a-chewing, and just then the explosion took place, and we all rushed in there, I tell you what I honestly think. I think that dog was chewing that box of parlor matches. This kind that pop so when you step on them. Pa was just going to set down when the whole air was filled with dog, and Pa, and rockets, and everything.”

“When I got in there Pa had a sofa pillow trying to put the dog out, and in the meantime Pa’s linen pants were afire. I grabbed a pail of this indigo water that they had been rinsing clothes with and throwed it on Pa, or there wouldn’t have been a place on him biggern a sixpence that wasn’t burnt, and then he threw a camp chair at me and told me to go to Gehenna. Ma says that’s the new hell they have got up in the revised edition of the Bible for bad boys. When Pa’s pants were out his coat-tail blazed up and a Roman candle was firing blue and red balls at his legs, and a rocket got into his white vest. The scene beggared description, like the Racine fire. A nigger chaser got after Ma and treed her on top of the sofa, and another one took after a girl that Ma invited to dinner, and burnt one of her stockings so she had to wear one of Ma’s stockings, a good deal too big for her, home. After things got a little quiet, and we opened the doors and windows to let out the smoke and the smell of burnt dog hair, and Pa’s whiskers, the big fire crackers began to go off, and a policeman came to the door and asked what was the matter, and Pa told him to go along with me to Gehenna, but I don’t want to go with a policeman. It would give me dead away. Well, there was nobody hurt much but the dog and Pa. I felt awful sorry for the dog. He hasn’t got hair enough to cover hisself. Pa, didn’t have much hair anyway, except by the ears, but he thought a good deal of his whiskers, cause they wasn’t very gray. Say, couldn’t you send this anarchy up to the house? If I go up there Pa will say I am the damest fool on record. This is the last 4th of July you catch me celebrating. I am going to work in a glue factory, where nobody will ever come to see me.”

And the boy went out to pick up some squib firecrackers, that had failed to explode, in front of the drug store.

CHAPTER V.

THE BAD BOY’S MA COMES HOME—NO DEVILTRY ONLY A LITTLE FUN—

THE BAD BOY’S CHUM—A LADY’S WARDROBE IN THE OLD MAN’S ROOM—

MA’S UNEXPECTED ARRIVAL—WHERE IS THE HUZZY?—DAMFINO!—THE

BAD BOY WANTS TO TRAVEL WITH A CIRCUS.

“When is your ma coming back?” asked the grocery man, of the bad boy, as he found him standing on the sidewalk when the grocery was opened in the morning, taking some pieces of brick out of his coat tail pockets.

“O she got back at midnight, last night,” said the boy, as he eat a few blue berries out of a case. “That’s what makes me up so early, Pa has been kicking at these pieces of brick with his bare feet, and when I came away he had his toes in his hand and was trying to go back up stairs on one foot. Pa haint got no sense.”

“I am afraid you are a terror,” said the grocery man, as he looked at the innocent face of the boy, “You are always making your parents some trouble, and it is a wonder to me they don’t send you to some reform school. What deviltry were you up to last night to get kicked this morning?”

“No deviltry, just a little fun. You see, Ma went to Chicago to stay a week, and she got tired, and telegraphed she would be home last night, and Pa was down town and I forgot to give him the dispatch, and after he went to bed, me and a chum of mine thought wo would have a 4th of July.

“You see, my chum has got a sister about as big as Ma, and we hooked some of her clothes and after P got to snoring we put them in Pa’s room. O, you’d a laffed. We put a pair of number one slippers with blue stockings, down in front of the rocking chair, beside Pa’s boots, and a red corset on a chair, and my chum’s sister’s best black silk dress on another chair, and a hat with a white feather on, on the bureau, and some frizzes on the gas bracket, and everything we could find that belonged to a girl in my mum’s sister’s room. O, we got a red parasol too, and left it right in the middle of the floor. Well, when I looked at the lay-out, and heard Pa snoring, I thought I should die. You see, Ma knows Pa is, a darn good feller, but she is easily excited. My chum slept with me that night, and when we heard the door bell ring I stuffed a pillow in my mouth, There was nobody to meet Ma at the depot, and she hired a hack and came right up. Nobody heard the bell but me, and I had to go down and let Ma in. She was pretty hot, now you bet, at not being met at the depot. “Where’s your father?” said she, as she began to go up stairs.

“I told her I guessed Pa had gone to sleep by this time, but I heard a good deal of noise in the room about an hour ago, and may be he was taking a bath. Then I slipped up stairs and looked over the banisters. Ma said something about heavens and earth, and where is the huzzy, and a lot of things I couldn’t hear, and Pa said damfino and its no such thing, and the door slammed and they talked for two hours. I s’pose they finally layed it to me, as they always do, ‘cause Pa called me very early this morning, and when I came down stairs he came out in the hall and his face was redder’n a beet, and he tried to stab me with his big toe-nail, and if it hadn’t been for these pieces of brick he would have hurt my feelings. I see they had my chum’s sister’s clothes all pinned up in a newspaper, and I s’pose when I go back I shall have to carry them home, and then she will be down on me. I’ll tell you what, I have got a good notion to take some shoemaker’s wax and stick my chum on my back and travel with a circus as a double headed boy from Borneo. A fellow could have more fun, and not get kicked all the time.”

And the boy sampled some strawberries in a case in front of the store and went down the street whistling for his chum, who was looking out of an alley to see if the coast was clear.

CHAPTER VI.

HIS PA IS A DARN COWARD—HIS PA HAS BEEN A MAJOR—-HOW HE

WOULD DEAL WITH BURGLARS—HIS BRAVERY PUT TO THE TEST—THE

ICE REVOLVER—HIS PA BEGINS TO PRAY—TELLS WHERE THE CHANGE

IS—“PLEASE MR. BURGLAR SPARE A POOR MAN’S LIFE!”—MA WAKES

UP—THE BAD BOY AND HIS CHUM RUN—FISH-POLE SAUCE—MA WOULD

MAKE A GOOD CHIEF OF POLICE.

“I suppose you think my Pa is a brave man,” said the bad boy to the grocer, as he was trying a new can opener on a tin biscuit box in the grocery, while the grocer was putting up some canned goods for the boy, who said the goods where (sp.) for the folks to use at a picnic, but which was to be taken out camping by the boy and his chum.

“O I suppose he is a brave man,” said the grocer, as he charged the goods to the boy’s father. “Your Pa is called a major, and you know at the time of the reunion he wore a veteran badge, and talked to the boys about how they suffered during the war.”

“Suffered nothing,” remarked the boy with a sneer, “unless they suffered from the peach brandy and leather pies Pa sold them. Pa was a sutler, that’s the kind of a veteran he was, and he is a coward.”

“What makes you think your Pa is a coward?” asked the grocer, as he saw the boy slipping some sweet crackers into his pistol pocket.

“Well, my chum and me tried him last night, and he is so sick this morning that he can’t get up. You see, since the burglars got into Magie’s, Pa has been telling what he would do if the burglars got into our house. He said he would jump out of bed and knock one senseless with his fist, and throw the other over the banister. I told my chum Pa was a coward, and we fixed up like burglars, with masks on, and I had Pa’s long hunting boots on, and we pulled caps down over our eyes, and looked fit to frighten a policeman. I took Pa’s meerschaum pipe case and tied a little piece of ice over the end the stem goes in, and after Pa and Ma was asleep we went in the room, and I put the cold muzzle of the ice revolver to Pa’s temple, and when he woke up I told him if he moved a muscle or said a word I would spatter the wall and the counterpane with his brains. He closed his eyes and began to pray. Then I stood off and told him to hold up his hands, and tell me where the valuables was. He held up his hands, and sat up in bed, and sweat and trembled, and told us the change was in his left hand pants pocket, and that Ma’s money purse was in the bureau drawer in the cuff box, and my chum went and got them, Pa shook so the bed fairly squeaked and I told him I was a good notion to shoot a few holes in him just for fun, and he cried and said please Mr. Burglar, take all I have got, but spare a poor old man’s life, who never did any harm! Then I told him to lay down on his stomach and pull the clothes over his head, and stick his feet over the foot board, and he did it, and I took a shawl strap and was strapping his feet together, and he was scared, I tell you. It would have been all right if Ma hadn’t woke up. Pa trembled so Ma woke up and thought he had the ager, and my chum turned up the light to see how much there was in Ma’s purse, and Ma see me, and asked me what I was doing and I told her I was a burglar, robbing the house. I don’t know whether Ma tumbled to the racket or not, but she threw a pillow at me, and said “get out of here or I’ll take you across my knee,” and she got up and we run. She followed us to my room, and took Pa’s jointed fish pole and mauled us both until I don’t want any more burgling, and my chum says he will never speak to me again. I didn’t think Ma had so much sand. She is brave as a lion, and Pa is a regular squaw. Pa sent for me to come to his room this morning, but I ain’t well, and am going out to Pewaukee to camp out till the burglar scare is over. If Pa comes around here talking about war times, and how he faced the enemy on many a well fought field, you ask him if he ever threw any burglars down a banister. He is a frod (sp.), Pa is, but Ma would make a good chief of police, and don’t you let it escape you.”

And the boy took his canned ham and lobster, and tucking some crackers inside the bosom of his blue flannel shirt, started for Pewaukee, while the grocer looked at him as though he was a hard citizen.

CHAPTER VII.

HIS PA GETS A BITE—HIS PA GETS TOO MUCH WATER—THE DOCTOR’S

DISAGREE—HOW TO SPOIL BOYS—HIS PA GOES TO PEWAUKEE IN

SEARCH OF HIS SON—ANXIOUS TO FISH—“STOPER I’VE GOT A

WHALE!”—OVERBOARD—HIS PA IS SAVED—GOES TO CUT A SWITCH—

A DOLLAR FOR HIS PANTS.

“So the doctor thinks your Pa has ruptured a blood vessel, eh,” says the street car driver to the bad boy, as the youngster was playing sweet on him to get a free ride down town.

“Well, they don’t know. The doctor at Pewaukee said Pa had dropsy, until he found the water that they wrung out of his pants was lake water, and there was a doctor on the cars belonging to the Insane Asylum, when we put Pa on the train, who said from the looks of his face, sort of red and blue, that it was apoplexy, but a horse doctor that was down at the depot when we put Pa in the carriage to take him home, said he was off his feed, and had been taking too much water when he was hot, and got foundered. O, you can’t tell anything about doctors. No two of ‘em guesses alike,” answered the boy, as he turned the brake for the driver to stop the car for a sister of charity, and then punched the mule with a fish pole, when the driver was looking back, to see if he couldn’t jerk her off the back step.

“Well, how did your Pa happen to fall out of the boat? Didn’t he know the lake was wet?”

“He had a suspicion that it was damp, when his back struck the water, I think. I’ll tell you how it was. When my chum and I run away to Pewaukee, Ma thought we had gone off to be piruts, and she told Pa it was a duty he owed to society to go and get us to come back, and be good. She told him if he would treat me as an equal, and laugh and joke with me, I wouldn’t be so bad. She said kicking and pounding spoiled more boys than all the Sunday schools. So Pa came out to our camp, about two miles up the lake from Pewaukee, and he was just as good natured as though we had never had any trouble at all. We let him stay all night with us, and gave him a napkin with a red border to sleep on under a tree, cause there was not blankets enough to go around, and in the morning I let him have one of the soda crackers I had in my shirt bosom and he wanted to go fishing with us. He said he would show us how to fish. So he got a piece of pork rind at a farm house for bait, and put it on a hook, and we got in an old boat, and my chum rowed and Pa and I trolled. In swinging the boat around Pa’s line got under the boat, and come right up near me. I don’t know what possessed me, but I took hold of Pa’s line and gave it a “yank,” and Pa jumped so quick his hat went off in the lake.”

“Stoper,” says Pa, “I’ve got a whale.” It’s mean in a man to call his chubby faced little boy a whale, but the whale yanked again and Pa began to pull him in. I hung on, and let the line out a little at a time, just zackly like a fish, and he pulled, and sweat, and the bald spot on his head was getting sun burnt, and the line cut my hand, so I wound it around the oar-lock, and Pa pulled hard enough to tip the boat over. He thought he had a forty pound musculunger, and he stood up in the boat and pulled on that oar-lock as hard as he could. I ought not to have done it, but I loosened the line from the oar-lock, and when it slacked up Pa went right out over the side of the boat, and struck on his pants, and split a hole in the water as big as a wash tub. His head went down under water, and his boot heels hung over in the boat. “What you doin’? Diving after the fish?” says I as Pa’s head came up and he blowed out the water. I thought Pa belonged to the church, but he said “you damidyut.”

“I guess he was talking to the fish. Wall, sir, my chum took hold of Pa’s foot and the collar of his coat and held him in the stern of the boat, and I paddled the boat to the shore, and Pa crawled out and shook himself. I never had no ijee a man’-pants could hold so much water. It was just like when they pull the thing on a street sprinkler. Then Pa took off his pants and my chum and me took hold of the legs and Pa took hold of the summer kitchen, and we rung the water out. Pa want so sociable after that, and he went back in the woods with his knife; with nothing on but a linen duster and a neck-tie, while his pants were drying on a tree, to cut a switch, and we hollered to him that a party of picnicers from Lake Side were coming ashore right where his pants were, to pic-nic, and Pa he run into the woods. He was afraid there would be some wimmen in the pic-nic that he knowed, and he coaxed us to come in the woods where he was, and he said he would give us a dollar a piece and not be mad any more if we would bring him his pants. We got his pants, and you ought to see how they was wrinkled when he put them on. They looked as though they had been ironed with waffle irons. We went to the depot and came home on a freight train, and Pa sneezed all the way in the caboose, and I don’t think he has ruptured any blood vessel. Well, I get off here at Mitchell’s bank,” and the boy turned the brake and jumped off without paying his fare.

CHAPTER VIII.

HE IS TOO HEALTHY. AN EMPTY CHAMPAGNE BOTTLE AND A BLACK

EYE—HE IS ARRESTED—OCONOMOWOC FOR HEALTH—HIS PA IS AN OLD

MASHER—DANCED TILL THE COWS CAME HOME—THE GIRL PROM THE

SUNNY SOUTH—THE BAD BOY IS SENT HOME.

“There, I knew you would get into trouble,” said the grocery man to the bad boy, as a policeman came along leading him by the ear, the boy having an empty champagne bottle in one hand, and a black eye. “What has he been doing Mr. Policeman?” asked the grocery man, as the policeman halted with the boy in front of the store.

“Well, I was going by a house up here when this kid opened the door with a quart bottle of champagne, and he cut the wire and fired the cork at another boy, and the champagne went all over the sidewalk, and some of it went on me, and I knew there was something wrong, cause champagne is to expensive to waste that way, and he said he was running the shebang and if I would bring him here you would say he was all right. If you say so I will let him go.”

The grocery man said he had better let the boy go, as his parents would not like to have their little pet locked up. So the policeman let go his ear, and he throwed the empty bottle at a coal wagon, and after the policeman had brushed the champagne off his coat, and smelled of his fingers, and started off, the grocery man turned to the boy, who was peeling a cucumber, and said:

“Now, what kind of a circus have you been having, and what do you mean by destroying wine that way! and where are your folks?”

“Well, I’ll tell you. Ma she has got the hay fever and has gone to Lake Superior to see if she can’t stop sneezing, and Saturday Pa said he and me would go out to Oconomowoc and stay over Sunday, and try and recuperate our health. Pa said it would be a good joke for me not to call him Pa, but to act as though I was his younger brother, and we would have a real nice time. I knowed what he wanted. He is an old masher, that’s what’s the matter with him, and he was going to play himself for a batchelor. O, thunder, I got on to his racket in a minute. He was introduced to some of the girls and Saturday evening he danced till the cows come home. At home he is awful fraid of rheumatic, and he never sweats, or sits in a draft; but the water just poured off’n him, and he stood in the door and let a girl fan him till I was afraid he would freeze, and just as he was telling a girl from Tennessee, who was joking him about being a nold batch, that he was not sure as he could always hold out a woman hater if he was to be thrown into contact with the charming ladies of the Sunny South, I pulled his coat and said, ‘Pa how do you spose Ma’s hay fever is to-night. I’ll bet she is just sneezing the top of her head off.” Wall, sir, you just oughten seen that girl and Pa. Pa looked at me as if I was a total stranger, and told the porter if that freckled faced boot-black belonged around the house he had better be fired out of the ball-room, and the girl said the disgustin’ thing, and just before they fired me I told Pa he had better look out or he would sweat through his liver pad.

“I went to bed and Pa staid up till the lights were put out. He was mad when he came to bed, but he didn’t lick me, cause the people in the next room would hear him, but the next morning he talked to me. He said I might go back home Sunday night, and he would stay a day or two. He sat around on the veranda all the afternoon, talking with the girls, and when he would see me coming along he would look cross. He took a girl out boat riding, and when I asked him if I couldn’t go along, he said he was afraid I would get drowned, and he said if I went home there was nothing there too good for me, and so my chum and me got to firing bottles of champane, and he hit me in the eye with a cork, and I drove him out doors and was just going to shell his earth works, when the policeman collared me. Say, what’s good for a black eye?”

The grocery man told him his Pa would cure it when he got home, “What do you think your Pa’s object was in passing himself off for a single man at Oconomowoc,” asked the grocery man, as he charged up the cucumber to the boy’s father.

“That’s what beats me. Aside from Ma’s hay fever she is one of the healthiest women in this town. O, I suppose he does it for his health, the way they all do when they go to a summer resort, but it leaves a boy an orphan, don’t it, to have such kitteny parents.”

CHAPTER IX.

HIS PA HAS GOT ‘EM AGAIN! HIS PA IS DRINKING HARD—HE HAS

BECOME A TERROR—A JUMPING DOG—THE OLD MAN IS SHAMEFULLY

ASSAULTED—“THIS IS A HELLISH CLIMATE MY BOY!”—HIS PA

SWEARS OFF—HIS MA STILL SNEEZING AT LAKE SUPERIOR.

‘“If the dogs in our neighborhood hold out I guess I can do something that all the temperance societies in this town have failed to do,” says the bad boy to the grocery man, as he cut off a piece of cheese and took a handful of crackers out of a box.

“Well for Heaven’s sake, what have you been doing now, you little reprobate,” asked the grocery man, as he went to the desk and charged the boy’s father with a pound and four ounces of cheese and two pounds of crackers. “If you was my boy and played any of your tricks on me I would maul the everlasting life out of you. Your father is a cussed fool that he dont send you to the reform school. The hired girl was over this morning and says your father is sick, and I should think he would be. What you done? Poisoned him I suppose.”

“No, I didn’t poison him; I just scared the liver out of him that’s all.”

“How was it,” asked the groceryman, as he charged up a pound of prunes to the boy’s father.

“Well, I’ll tell you, but if you ever tell Pa I wont trade here any more. You see, Pa belongs to all the secret societies, and when there is a grand lodge or anything here, he drinks awfully. There was something last week, some sort of a leather apron affair, or a sash over the shoulder, and every night he was out till the next day, and his breath smelled all the time like in front of a vinegar store, where they keep yeast. Ever since Ma took her hay fever with her up to Lake Superior, Pa has been a terror, and I thought something ought to be done. Since that variegated dog trick was played on him he has been pretty sober till Ma went away, and I happened to think of a dog a boy in the Third Ward has got, that will do tricks. He will jump up and take a man’s hat off, and bring a handkerchief, and all that. So I got the boy to come up on our street, and Monday night, about dark, I got in the house and told the boy when Pa came along to make the dog take his hat, and to pin a handkerchief to Pa’s coat tail and make the dog take that, and then for him and the dog to lite out for home. Well, you’d a dide. Pa came up the street as dignified and important as though he had gone through bankruptcy, and tried to walk straight, and just as he got near the door the boy pointed to Pa’s hat and said, “Fetch it!” The dog is a big Newfoundland, but he is a jumper, and don’t you forget it. Pa is short and thick, and when the dog struck him on the shoulder and took his hat Pa almost fell over, and then he said get out, and he kicked and backed up toward the step, and then turned around and the boy pointed to the handkerchief and said, “fetch it,” and the dog gave one bark and went for it, and got hold of it and a part of Pa’s duster, and Pa tried to climb up the steps on his hands and feet, and the dog pulled the other way, and it is an old last year’s duster anyway, and the whole back breadth come out, and when I opened the door there Pa stood with the front of his coat and the sleeves on, but the back was gone, and I took hold of his arm, and he said, “Get out,” and was going to kick me, thinking I was a dog, and I told him I was his own little boy, and asked him if anything was the matter, and he said, “M (hic) atter enough. New F (hic) lanp dog chawing me last hour’n a half. Why didn’t you come and k (hic) ill’em?” I told Pa there was no dog at all, and he must be careful of his health or I wouldn’t have no Pa at all. He looked at me and asked me, as he felt for the place where the back of his linen duster was, what had become of his coat-tail and hat if there was no dog, and I told him he had probably caught his coat on that barbed wire fence down street, and he said he saw the dog and a boy just as plain as could be, and for me to help him up stairs and go for the doctor. I got him to the bed, and he said, “this is a hellish climate my boy,” and I went for the doctor. Pa said he wanted to be cauterised, so he wouldn’t go mad. I told the doc. the Joke, and he said he would keep it up, and he gave Pa some powders, and told him if he drank any more before Christmas he was a dead man. Pa says it has learned him a lesson and they can never get any more pizen down him, but don’t you give me away, will you, cause he would go and complain to the police about the dog, and they would shoot it. Ma will be back as soon as she gets through sneezing, and I will tell her, and she will give me a cho-meo, cause she dont like to have Pa drink only between meals. Well, good day. There’s a Italian got a bear that performs in the street, and I am going to find where he is showing, and feed the bear a cayenne pepper lozenger, and see him clean out the Pollack settlement. Good bye.”

And the boy went to look for the bear.

CHAPTER X.

HIS PA HAS GOT RELIGION—THE BAD BOY GOES TO SUNDAY SCHOOL—

PROMISES REFORMATION—THE OLD MAN ON TRIAL FOR SIX MONTHS—

WHAT MA THINKS—ANTS IN PA’S LIVER-PAD—THE OLD MAN IN

CHURCH—RELIGION IS ONE THING—ANTS ANOTHER.

“Well, that beats the devil,” said the grocery man, as he stood in front of his grocery and saw the bad boy coming along, on the way home from Sunday school, with a clean shirt on, and a testament and some dime novels under his arm. “What has got into you, and what has come over your Pa. I see he has braced up, and looks pale and solemn. You haven’t converted him have you?”

“No, Pa has not got religion enough to hurt yet, but he has got the symptoms. He has joined the church on prowbation, and is trying to be good so he can get in the church for keeps. He said it was hell living the way he did, and he has got me to promise to go to Sunday school. He said if I didn’t he would maul me so my skin wouldn’t hold water. You see, Ma said Pa had got to be on trial for six months before he could get in the church, and if he could get along without swearing and doing anything bad, he was all right, and we must try him and see if we could cause him to swear. She said she thought a person, when they was on a prowbation, ought to be a martyr, and try and overcome all temptations to do evil, and if Pa could go through six months of our home life, and not cuss the hinges off the door, he was sure of a glorious immortality beyond the grave. She said it wouldn’t be wrong for me to continue to play innocent jokes on Pa, and if he took it all right he was a Christian but if he got a hot box, and flew around mad, he was better out of church than in it. There he comes now,” said the boy as he got behind a sign, “and he is pretty hot for a Christian. He is looking for me. You had ought to have seen him in church this morning. You see, I commenced the exercises at home after breakfast by putting a piece of ice in each of Pa’s boots, and when he pulled on the boots he yelled that his feet were all on fire, and we told him that it was nothing but symptoms of gout, so he left the ice in his boots to melt, and he said all the morning that he felt as though he had sweat his boots full. But that was not the worst. You know, Pa he wears a liver-pad. Well, on Saturday my chum and me was out on the lake shore and we found a nest of ants, these little red ants, and I got a pop bottle half full of the ants and took them home. I didn’t know what I would do with the ants, but ants are always handy to have in the house. This morning, when Pa was dressing for church, I saw his liver-pad on a chair, and noticed a hole in it, and I thought what a good place it would be for the ants. I don’t know what possessed me, but I took the liver-pad into my room, and opened the bottle, and put the hole over the mouth of the bottle and I guess the ants thought there was something to eat in the liver-pad, cause they all went into it, and they crawled around in the bran and condition powders inside of it, and I took it back to Pa, and he put it on under his shirt, and dressed himself, and we went to church. Pa squirmed a little when the minister was praying, and I guess some of the ants had come out to view the landscape o’er. When we got up to sing the hymn Pa kept kicking, as though he was nervous, and he felt down his neck and looked sort of wild, this way he did when he had the jim-jams. When we sat down Pa couldn’t keep still, and I like to dide when I saw some of the ants come out of his shirt bosom and go racing around his white vest. Pa tried to look pious, and resigned, but he couldn’t keep his legs still, and he sweat mor’n a pail full. When the minister preached about “the worm that never dieth,” Pa reached into his vest and scratched his ribs, and he looked as though he would give ten dollars if the minister would get through. Ma she looked at Pa as though she would bite his head off, but Pa he just squirmed, and acted as though his soul was on fire. Say, does ants bite, or just crawl around? Well, when the minister said amen, and prayed the second round, and then said a brother who was a missionary to the heathen would like to make a few remarks about the work of the missionaries in Bengal, and take up a collection, Pa told Ma they would have to excuse him, and he lit out for home, slapping himself on the legs and on the arms and on the back, and he acted crazy. Ma and me went home, after the heathen got through, and found Pa in his bed room, with part of his clothes off, and the liver-pad was on the floor, and Pa was stamping on it with his boots, and talking offul.

“What is the matter,” says Ma.. “Don’t your religion agree with you?”

“Religion be dashed,” says Pa, as he kicked the liver pad. “I would give ten dollars to know how a pint of red ants got into my liver pad. Religon is one thing, and a million ants walking all over a man, playing tag, is another. I didn’t know the liver pad was loaded. How in Gehenna did they get in there?” and Pa scowled at Ma as though he would kill her.

“‘Don’t swear dear,” says Ma, as she threw down her hymn book, and took off her bonnet. “You should be patient. Remember Job was patient, and he was afflicted with sore boils.”

“I don’t care,” says Pa, as he chased the ants out of his drawers, “Job never had ants in his liver pad. If he had he would have swore the shingles off a barn. Here you,” says Pa, speaking to me, “you head off them ants running under the bureau. If the truth was known I believe you would be responsible for this outrage.” And Pa looked at me kind of hard.

“O, Pa,” says I, with tears in my eyes, “Do you think your little Sunday school boy would catch ants in a pop bottle on the lake shore, and bring them home, and put them in the hole of your liver pad, just before you put it on to go to church? You are to (sp.) bad.” And I shed some tears. I can shed tears now any time I want to, but it didn’t do any good this time. Pa knew it was me, and while he was looking for the shawl strap I went to Sunday school, and now I guess he is after me, and I will go and take a walk down to Bay View.

The boy moved off as his Pa turned a corner, and the grocery man said, “Well, that boy beats all I ever saw. If he was mine I would give him away.”

CHAPTER XI.

HIS PA TAKES A TRICK—JAMAICA RUM AND CARDS—THE BAD BOY

POSSESSED OF A DEVIL—THE KIND DEACON—AT PRAYER MEETING—

THE OLD MAN TELLS HIS EXPERIENCE—THE FLYING CARDS—THE

PRAYER MEETING SUDDENLY CLOSED.

“What is it I hear about your Pa being turned out of prayer meeting Wednesday night,” asked the grocer of the bad boy, as he came over after some cantelopes for breakfast, and plugged a couple to see if they were ripe.

“He wasn’t turned out of prayer meeting at all. The people all went away and Pa and me was the last ones out of the church. But Pa was mad, and don’t you forget it.”

“Well, what seemed to be the trouble? Has your Pa become a backslider?”

“O, no, his flag is still there. But something seems to go wrong. You see, when we got ready to go to prayer meeting last night. Pa told me to go up stairs and get him a hankerchief, and to drop a little perfumery on it, and put it in the tail pocket of his black coat. I did it, but I guess I got hold of the wrong bottle of fumery. There was a label on the fumery bottle that said ‘Jamaica Rum,’ and I thought it was the same as Bay Rum, and I put on a whole lot. Just afore I put the hankerchief in Pa’s pocket, I noticed a pack of cards on the stand, that Pa used to play hi lo-jack with Ma evenings when he was so sick he couldn’t go down town, before he got ‘ligion, and I wrapped the hankercher around the pack of cards and put them in his pocket. I don’t know what made me do it, and Pa don’t, either, I guess, ‘cause he told Ma this morning I was possessed of a devil. I never owned no devil, but I had a pair of pet goats onct, and they played hell all around, Pa said. That’s what the devil does, ain’t it? Well, I must go home with these melons, or they won’t keep.”

“But hold on,” says the grocery man as he gave the boy a few rasins with worms in, that he couldn’t sell, to keep him, “what about the prayer meeting?”

“O, I like to forgot. Well Pa and me went to prayer meeting, and Ma came along afterwards with a deakin that is mashed on her, I guess, ‘cause he says she is to be pitted for havin’ to go through life yoked to such an old prize ox as Pa. I heard him tell Ma that, when he was helping her put on her rubber waterprivilege to go home in the rain the night of the sociable, and she looked at him just as she does at me when she wants me to go down to the hair foundry after her switch, and said, “O, you dear brother,” and all the way home he kept her waterprivilege on by putting his arm on the small of her back. Ma asked Pa if he didn’t think the deakin was real kind, and Pa said, “yez, dam kind,” but that was afore he got ‘ligion. We sat in a pew, at the prayer meeting, next to Ma and the deakin, and there was lots of pious folks all round there. After the preacher had gone to bat, and an old lady had her innings, a praying, and the singers had got out on first base, Pa was on deck, and the preacher said they would like to hear from the recent convert, who was trying to walk in the straight and narrow way, but who found it so hard, owing to the many crosses he had to bear. Pa knowed it was him that had to go to bat, and he got up and said he felt it was good to be there. He said he didn’t feel that he was a full sized Christian yet, but he was getting in his work the best he could. He said at times everything looked dark to him, and he feared he should falter by the wayside, but by a firm resolve he kept his eye sot on the future, and if he was tempted to do wrong he said get thee behind me, Satan, and stuck in his toe-nails for a pull for the right. He said he was thankful to the brothers and sisters, particularly the sisters, for all they had done to make his burden light, and hoped to meet them all in—When Pa got as far as that he sort of broke down, I spose he was going to say heaven, though after a few minutes they all thought he wanted to meet them in a saloon. When his eyes began to leak, Pa put his hand in his tail pocket for his handkercher, and got hold of it, and gave it a jerk, and out came the handkercher, and the cards. Well, if he had shuffled them, and Ma had cut them, and he had dealt six hands, they couldn’t have been dealt any better. They flew into everybody’s lap. The deakin that was with Ma got the jack of spades and three aces and a deuce, and Ma got some nine spots and a king of hearts, and Ma nearly fainted, cause she didn’t get a better hand, I spose. The preacher got a pair of deuces, and a queen of hearts, and he looked up at Pa as though it was a misdeal, and a old woman who sat across the aisle, she only got two cards, but that was enough. Pa didn’t see what he done at first, cause he had the handkerchief over his eyes, but when he smelled the rum on it, he took it away, and then he saw everybody discarding, and he thought he had struck a poker game, and he looked around as though he was mad cause they didn’t deal him a hand. The minister adjourned the prayer meeting and whispered to Pa, and everybody went out holding their noses on account of Pa’s fumery, and when Pa came home he asked Ma what he should do to be saved. Ma said she didn’t know. The deakin told her Pa seemed wedded to his idols. Pa said the deakin better run his own idols, and Pa would run his. I don’t know how it is going to turn out, but Pa says he is going to stick to the church.”

CHAPTER XII.

HIS PA GETS PULLED. THE OLD MAN STUDIES THE BIBLE—DANIEL IN

THE LION’S DEN—THE MULE AND THE MULE’S FATHER—MURDER IN

THE THIRD WARD—THE OLD MAN ARRESTED—THE OLD MAN FANS THE

DUST OUT OF HIS SON’S PANTS.

“What was you and your Ma down to the police station for so late last night?” asked the grocery man of the bad boy, as he kicked a dog away from a basket of peaches standing on the sidewalk “Your Ma seemed to be much affected.”

“That’s a family secret. But if you will give me some of those rotton peaches I will tell you, if you won’t ever ask Pa how he came to be pulled by the police.”

The grocery man told him to help himself out of the basket that the dog had been smelling of, and he filled his pockets, and the bosom of his flannel shirt, and his hat, and said:

“Well, you know Pa is studying up on the Bible, and he is trying to get me interested, and he wants me to ask him questions, but if I ask him any questions that he can’t answer, he gets mad. When I asked him about Daniel in the den of lions, and if he didn’t think Dan was traveling with a show, and had the lions chloroformed, he said I was a scoffer, and would go to Gehenna. Now I don’t want to go to Gehenna just for wanting to get posted in the show business of old times, do you? When Pa said Dan was saved from the jaws of the lions because he prayed three times every day, and had faith, I told him that was just what the duffer that goes into the lions den in Coup’s circus did because I saw him in the dressing room, when me and my chum got in for carrying water for the elephant, and he was exhorting with a girl in tights who was going to ride two horses. Pa said I was mistaken, cause they never prayed in circus, ‘cept the lemonade butchers. I guess I know when I hear a man pray. Coup’s Daniel talked just like a deacon at class meeting, and told the girl to go to the place where the minister says we will all go if we don’t do different. Pa says it is wicked to speak of Daniel in the same breath that you speak of a circus, so I am wicked I ‘spose. Well, I couldn’t help it and when he wanted me to ask him questions about Elijah going up in a chariot of fire, I asked him if he believed a chariot like the ones in the circus, with eight horses, could carry a man right up to the clouds, and Pa said of course it could. Then I asked him what they did with the horses after they got up there, or if the chariot kept running back and forth like a bust to a pic-nic, and whether they had stalls for the horses and harness-makers to repair harnesses, and wagon-makers, cause a chariot is liable to run off a wheel, if it strikes a cloud in turning a corner. Pa said I made him tired. He said I had no more conception of the beauties of scripture than a mule, and then I told Pa he couldn’t expect a mule to know much unless the mule’s father had brought him up right, and where a mule’s father had been a regular old bummer till he got jim-jams, and only got religon to keep out of the inebriate asylum, that the little mule was entitled to more charity for his short comings than the mule’s Papa. That seemed to make Pa mad, and he said the scripture lesson would be continued some other time, and I might go out and play, and if I wasn’t in before nine o’clock he would come after me and warm my jacket. Well, I was out playing, and me and my chum heard of the murder in the Third Ward, and went down there to see the dead and wounded, and it was after ten o’clock, and Pa was searching for me, and I saw Pa go into an alley, in his shirt sleves and no hat on, and the police were looking for the murderer, and I told the policeman that there was a suspicious looking man in the alley, and the policeman went in there and jumped on his back, and held him down, and the patrol wagon came, and they loaded Pa in, and he gnashed his teeth, and said they would pay dearly for this, and they held his hands and told him not to talk, as he would commit himself, and they tore off his suspender buttons, and I went home and told Ma the police had pulled Pa for being in a suspicious place, and she said she had always been afraid he would come to some bad end, and we went down to the station and the police let Pa go on promise that he wouldn’t do so again, and we went home and Pa fanned the dust out of my pants. But he did it in a pious manner, and I can’t complain. He was trying to explain to Ma how it was that he was pulled, when I came away, and I guess he will make out to square himself. Say, don’t these peaches seem to have a darn queer taste. Well, good bye. I am going down to the morgue to have some fun.”

CHAPTER XIII.

HIS PA GOES TO THE EXPOSITION. THE BAD BOY ACTS AS GUIDE—

THE CIRCUS STORY—THE OLD MAN WANTS TO SIT DOWN—TRIES TO

EAT PANCAKES—DRINKS SOME MINERAL WATER—THE OLD MAN FALLS

IN LOVE WITH A WAX WOMAN—A POLICEMAN INTERFERES—THE LIGHTS

GO OUT—THE GROCERY-MAN DON’T WANT A CLERK.

“Well, everything seems to be quiet over to your house this week,” says the groceryman to the bad boy, as the youth was putting his thumb into some peaches through the mosquito netting over the baskets, to see if they were soft enough to steal, “I suppose you have let up on the old man, haven’t you?”

“O, no. We keep it right up. The minister of the church that Pa has joined says while Pa is on probation it is perfectly proper for us to do everything to try him, and make him fall from grace. The minister says if Pa comes out of his six months probation without falling by the wayside he has got the elements to make the boss christian, and Ma and me are doing all we can.”

“What was the doctor at your house for this morning?” asked the groceryman, “Is your Ma sick?”

“No, Ma is worth two in the bush. It’s Pa that ain’t well. He is having some trouble with his digestion. You see he went to the exposition with me as guide, and that is enough to ruin any man’s digestion. Pa is near-sighted, and he said he wanted me to go along and show him things. Well, I never had so much fun since Pa fell out of the boat. First we went in by the fountain, and Pa never had been in the exposition building before. Last year he was in Yourip, and he was astonished at the magnitude of everything. First I made him jump clear across the aisle there, where the stuffed tigers are, by the fur place. I told him the keeper was just coming along with some meat to feed the animals, and when they smelled the meat they just clawed things. He run against a show-case, and then wanted to go away.

“He said he traveled with a circus when he was young, and nobody knew the dangers of fooling around wild animals better than he did. He said once he fought with seven tigers and two Nubian lions for five hours, with Mabee’s old show. I asked him if that was afore he got religin, and he said never you mind. He is an old liar, even if he is converted. Ma says he never was with a circus, and she has known him ever since he wore short dresses. Wall, you would a dide to see Pa there by the furniture place, where they have got beautiful beds and chairs. There was one blue chair under a glass case, all velvet, and a sign was over it, telling people to keep their hands off. Pa asked me what the sign was, and I told him it said ladies and gentlemen are requested to sit in the chairs and try them. Pa climbed over the railing and was just going to sit down on the glass show case over the chair, when one of the walk-around fellows, with imitation police hats, took him by the collar and yanked him back over the railing, and was going to kick Pa’s pants. Pa was mad to have his coat collar pulled up over his head, and have the set of his coat spoiled, and he was going to sass the man, when I told Pa the man was a lunatic from the asylum, that was on exhibition, and Pa wanted to go away from there. He said he didn’t know what they wanted to exhibit lunatics for. We went up stairs to the pancake bazar, where they broil pancakes out of self rising flour, and put butter and sugar on them and give them away. Pa said he could eat more pancakes than any man out of jail, and wanted me to get him some. I took a couple of pancakes and tore out a piece of the lining of my coat and put it between the pancakes and handed them to Pa, with a paper around the pancakes. Pa didn’t notice the paper nor the cloth, and it would have made you laff to see him chew on them. I told him I guessed he didn’t have as good teeth as he used to, and he said never you mind the teeth, and he kept on until he swallowed the whole business, and he said he guessed he didn’t want any more. He is so sensitive about his teeth that he would eat a leather apron if anybody told him he couldn’t. When the doctor said Pa’s digestion was bad, I told him if he could let Pa swallow a seamstress or a sewing machine, to sew up the cloth, he would get well, and the Doc. says I am going to be the death of Pa some day. But I thought I should split when Pa wanted a drink of water. I asked him if he would druther have mineral water, and he said he guessed it would take the strongest kind of mineral water to wash down them pancakes, so I took him to where the fire extinguishers are, and got him to take the nozzle of the extinguisher in his mouth, and I turned the faucet. I don’t think he got more than a quart of the stuff out of the saleratus machine down him, but he rared right up and said he be condamed if believed that water was ever intended to drink, and he felt as though he should bust, and just then the man who kicks the big organ struck up and the building shook, and I guess Pa thought he had busted. The most fun was when we came along to where the wax woman is. They have got a wax woman dressed up to kill, and she looks just as natural as if she could breathe. She had a handkerchief in her hand, and as we came along I told Pa there was a lady that seemed to know him. Pa is on the mash himself, and he looked at her and smiled and said good evening, and asked me who she was.

“I told him it looked to me like the girl that sings in the choir at our church, and Pa said corse it is, and he went right in where she was and said “pretty good show, isn’t it,” and put out his hand to shake hands with her, but the woman who tends the stand came along and thought Pa was drunk and said “old gentleman I guess you had better get out of here. This is for ladies only.”

“Pa said he didn’t care nothing about her lady’s only, all he wanted was to converse with an acquaintance, and then one of the policemen came along and told Pa he had better go down to the saloon where he belonged. Pa excused himself to the wax woman, and said he would see her later, and told the policeman if he would come out on the sidewalk he would knock leven kinds of stuffin out of him. The policeman told him that would be all right, and I led Pa away. He was offul mad. But it was the best fun when the lights went out. You see the electric light machine slipped a cog, or lost its cud, and all of a sudden the lights went out and it was as dark as a squaw’s pocket. Pa wanted to know what made it so dark, and I told him it was not dark. He said boy don’t you fool me. You see I thought it would be fun to make Pa believe he was struck blind, so I told him his eyes must be wrong. He said do you mean to say you can see, and I told him everything was as plain as day, and I pointed out the different things, and explained them, and walked Pa along, and acted just as though I could see, and Pa said it had come at last. He had felt for years as though he would some day lose his eyesight and now it had come and he said he laid it all to that condamned mineral water. After a little they lit some of the gas burners, and Pa said he could see a little, and wanted to go home, and I took him home. When we got out of the building he began to see things, and said his eyes were coming around all right. Pa is the easiest man to fool ever I saw.”

“Well, I should think he would kill you,” said the grocery man. “Don’t he ever catch on, and find out you have deceived him?”

“O, sometimes. But about nine times in ten I can get away with him. Say, don’t you want to hire me for a clerk?”

The grocery man said that he had rather have a spotted hyena, and the boy stole a melon and went away.

CHAPTER XIV.

HIS PA CATCHES OK—TWO DAYS AND NIGHTS IN THE BATH ROOM—

RELIGION CAKES THE OLD MAN’S BREAST—THE BAD BOY’S CHUM—

DRESSED UP AS A GIRL—THE OLD MAN DELUDED—THE COUPLE START

FOR THE COURT HOUSE PARK—HIS MA APPEARS ON THE SCENE—“IF

YOU LOVE ME KISS ME”—MA TO THE RESCUE—“I AM DEAD AM I?”

HIS PA THROWS A CHAIR THROUGH THE TRANSOM.

“Where have you been for a week back,” asked the grocery man of the bad boy, as the boy pulled the tail board out of the delivery wagon accidentally and let a couple of bushels of potatoes roll out into the gutter. “I haven’t seen you around here, and you look pale. You haven’t been sick, have you?”

“No, I have not been sick. Pa locked me up in the bath-room for two days and two nights, and didn’t give me nothing to eat but bread and water. Since he has got religious he seems to be harder than ever on me. Say, do you think religion softens a man’s heart, or does it give him a caked breast? I ‘spect Pa will burn me at the stake next.”

The grocery man said that when a man had truly been converted his heart was softened, and he was always looking for a chance to do good and be kind to the poor, but if he only had this galvanized religion, this roll plate piety, or whitewashed reformation, he was liable to be a harder citizen than before. “What made your Pa lock you up in the bath-room on bread and water?” he asked.