« back

|

TOM SLADE

BY

Author of

Illustrated by

Published With the Approval of

GROSSET & DUNLAP |

Copyright, 1918, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Contents

| I | Tom Makes a Promise | 1 | |

| II | "Bull Head" And "Butter Fingers" | 13 | |

| III | Roscoe Bent | 21 | |

| IV | The Cup of Joy | 27 | |

| V | The Main Trail | 40 | |

| VI | Tom And the Gold Cross | 49 | |

| VII | The Trail Runs Through a Pestilent Place | 56 | |

| VIII | An Accident | 60 | |

| IX | Roscoe Joins the Colors | 66 | |

| X | Tom And Roscoe Come to Know Each Other | 70 | |

| XI | Tom Meets a Stranger | 79 | |

| XII | Tom Hears of the Blond Beast | 85 | |

| XIII | As Others Saw Him | 93 | |

| XIV | Tom Gets a Job | 101 | |

| XV | The Excited Passenger | 109 | |

| XVI | Tom Makes a Discovery | 116 | |

| XVII | One of the Blond Beast's Weapons | 124 | |

| XVIII | Sherlock Nobody Holmes | 129 | |

| XIX | The Time of Day | 137 | |

| XX | A New Job | 145 | |

| XXI | Into the Danger Zone | 152 | |

| XXII | S O S | 160 | |

| XXIII | Roy Blakeley Keeps Still—For a Wonder | 172 | |

| XXIV | A Soldier's Honor | 181 | |

| XXV | The Face | 190 | |

| XXVI | Roscoe Bent Breaks His Promise | 199 | |

| XXVII | The End of the Trail | 215 |

TOM SLADE WITH THE COLORS

CHAPTER I

TOM MAKES A PROMISE

Tom Slade hoisted up his trousers, tightened his belt, and lounged against the railing outside the troop room, listening dutifully but rather sullenly to his scoutmaster.

"All I want you to do, Tom," said Mr. Ellsworth, "is to have a little patience—just a little patience."

"A little tiny one—about as big as Pee-wee," added Roy.

"A little bigger than that, I'm afraid," laughed Mr. Ellsworth, glancing at Pee-wee, who was adjusting his belt axe preparatory to beginning his perilous journey homeward through the wilds of Main Street.

"Just a little patience," repeated the scoutmaster, rapping Tom pleasantly on the shoulder.2

"Don't be like the day nursery," put in Roy. "All their trouble is caused by having very little patients."

"Very bright," said Mr. Ellsworth.

"Eighteen candle power," retorted Roy. "I ought to have ground glass to dim the glare, hey?"

The special scout meeting, called to make final preparations for the momentous morrow, had just closed; the other scouts had gone off to their several homes, and these three—Tom Slade, Roy Blakeley and Walter Harris (alias Pee-wee)—were lingering on the sidewalk outside the troop room for a few parting words with "our beloved scoutmaster," as Roy facetiously called Mr. Ellsworth.

As they talked, the light in the windows disappeared, for "Dinky," the church sexton, was in a hurry to get around to Matty's stationery store to complete his humdrum but patriotic duty of throwing up a wooden railing to keep the throng in line in the morning.

"The screw driver is mightier than the sword, hey, Dink?" called the irrepressible Roy, as Dinky hurried away into the darkness.

"All I wanted to say, Tom," said Mr. Ellsworth3 soberly, "is just this: let me do your thinking for you—even your patriotic thinking—for the time being. Do you get me? Don't run off and do anything foolish."

"Is it foolish to fight for your country?" asked Tom doggedly.

"It might be," retorted the scoutmaster, nothing daunted.

"I'm not going to stay here and see people drowned by submarines," muttered Tom.

"You won't see them drowned by submarines as long as you stay here, Tomasso," said Roy mischievously. He loved to make game of Tom's clumsy speech.

"You know what I mean," said Tom; "I ain't going to be a slacker for anybody."

"You might as well say that President Wilson is a slacker because he doesn't go off and enlist in some regiment," said Mr. Ellsworth; "or that Papa Joffre is a coward because he doesn't waste his time with a rifle in the trenches."

"Gee whiz, you can't say he's a coward," exclaimed Pee-wee, "because I saw him!"

"Of course, that proves he isn't a coward," said Roy slyly.

"There's going to be work, and a whole lot of4 it, for every one to do, Tom," continued Mr. Ellsworth pleasantly. "There is going to be work for old men and young men, for women and girls and boys—and scouts. And being a slacker consists in not doing the work which you ought to do. If a girl has a flower bed where she might grow tomatoes, and she grows roses there instead, you might call her a slacker.

"The officials in Washington who have this tremendous burden on their shoulders have told us what we, as scouts (Mr. Ellsworth always called himself a scout), ought to do. They have outlined a program for us. Now if you run off and join the army in the hope of doing a man's work, why then some man has got to knuckle down and do your work. See?"

"I'm sick of boring holes in sticks," grunted Tom.

"Well, I dare say you are. I never said it was as pleasant as eating ice cream. What I say is that we must all knuckle down and do what we can do best to help defend Old Glory. And we can't always choose our work for ourselves. I'm going to stay here, for the present, at least, and keep you scouts busy. And I don't consider that I'm a slacker either. If you all stand by me and5 help, I can be of more service right here, just now, than I could be if I went away."

"Then why does the government have posters out all around, urging fellers to join the army?" said Tom, unconvinced.

"There are fellers and fellers," said Mr. Ellsworth, mimicking Tom's pronunciation of the word, "and what is best for one isn't necessarily best for another. These posters are for fellows older than you, as you know perfectly well. I'm talking now of what is best for you—at present. Won't you trust me? If you can't obey and trust your scoutmaster, you couldn't obey and trust your captain and your general."

"I never said I didn't," said Tom.

"Well, then, leave it to me. When the time comes for you to join the army, I'll tell you so, and I'll shout it so loud that you can't make any mistake. Meanwhile, put aside all that idea and knuckle down and help. You're just as much with the colors now as if you were in the trenches.... You'll be on hand early to-morrow?"

"I s'pose so," said Tom sullenly.

Mr. Ellsworth looked at him steadily. No doubt it was something in Tom's grudging manner that made him apprehensive, but perhaps too6 as he looked at the boy who had been growing up before his eyes in the past two years, he realized as he had not realized before that Tom had come to be a pretty fine specimen and could stand unconcerned, as he certainly would, at the most rigid and exacting physical test.

When Tom's rapid growth had brought the inevitable advent of long trousers, arousing the unholy mirth of Roy Blakeley and others, Mr. Ellsworth had experienced a jarring realization that the process had begun whereby his scouts would soon begin slipping away from him.

He had compromised with Time by making Tom a sort of assistant scoutmaster and encouraging Connie Bennett to work into Tom's place as leader of the Elk Patrol; and he had lived in continual dread lest Tom (who might be counted on for anything) discover his own size, as it were, and get the notion in his stubborn head that he was too big to be a scout at all.

But Tom had thought too much of the troop and of the Elks for that, and a new cause of apprehension for Mr. Ellsworth had arisen which now showed in every line of his face as he looked at Tom.

"I want you to promise me, Tom, that you7 won't try to enlist without my permission. If you'll say that and obey Rule Seven the same as you have always obeyed it, I'll be satisfied."

"How about Rule Ten?" said Tom, in his usual dogged, half-hearted manner; "a scout has got to be brave, he's got to face danger, he's——"

"You notice Rule Seven comes before Rule Ten," snapped Mr. Ellsworth. "They put them in the order of their importance. The men who made the Handbook knew what they were about. The question is just whether you're going to continue to respect Rule Seven, that's all."

Mr. Ellsworth knew how to handle Tom.

"Yes, I am," Tom said reluctantly.

"Then that's all there is to it. Give me your hand, Tom."

Tom put out his hand, and as the scoutmaster shook it his manner relaxed into the usual off-hand way which the scouts so liked and which had made him so popular among them.

"President Wilson wasn't in any great rush about going to war, and I don't want you to be in a hurry to get into a uniform. You're in a uniform already, if it comes to that. And the Secretary of War says our little old scout khaki is going to make itself felt. I'd be the last to preach8 slacking, and when it's time, if the time comes, I'll tell you.... You know, Tom," he added ruefully, "you're getting to be such a fine, strapping fellow that it makes me afraid you'd get away with it if you tried. I don't like to see you so big, Tom——"

"Don't you care," said Pee-wee soothingly, "I'm small still."

"If you were old enough, I wouldn't say anything against it," Mr. Ellsworth added. "But you're not, Tom. Some people don't seem to think there's anything wrong in a boy's lying about his age to get into the army. But I do, and I think you do—— Don't you?" he added anxiously.

"Y-e-es."

"Of course, you couldn't enlist without Mr. Temple's consent, he being your guardian, unless you lied—and I know you wouldn't do that."

"You didn't catch me in many, did you?"

"I never caught you in any, Tom."

"Well, then——"

"Well, then," concluded Mr. Ellsworth, "I guess we'd all better go home and get some sleep. We've got one strenuous day to-morrow."

"It's going to be a peach," said Roy, looking9 up at the stars. As they started to move away, Mr. Ellsworth instinctively extended his hand to Tom again.

"I have your promise, then?" said he.

"Y-e-s."

"I'm not stuck on that 'yes.'"

"Yes," said Tom, more briskly.

"That you won't do anything along that line till you consult me?"

"Don't do anything till you count ten," said Roy.

"Make it ten thousand," said Mr. Ellsworth.

"And after you've counted ten," put in Pee-wee, "if you decide to go, I'll go with you, by crinkums!"

"Go-o-d-night!" laughed Roy. "That ought to be enough to keep you at home, Tomasso!"

Tom smiled, half grudgingly, as he turned and started toward home.

"You don't think he'd really enlist, do you?" queried Roy, as he and Pee-wee and Mr. Ellsworth sauntered up the street.

"He won't now," said the scoutmaster. "I have his promise."

"Otherwise, do you think he would?"

"I think it extremely likely."10

"And lie about his age?"

Mr. Ellsworth screwed his face into a funny, puzzled look. "There's a good deal of that kind of thing going on," he said, "and I sometimes think the recruiting people wink at it, or perhaps they are just a little too ready to judge by physical appearance. Look how Billy Wade got through."

"He doesn't look eighteen," said Roy.

"Of course he doesn't. But he told them he was 'going on nineteen,' and so he was—just the same as Pee-wee is going on fifty."

Roy laughed.

"The honor of enlisting, the willingness to sacrifice one's life, seems to cover a multitude of sins in the eyes of some people," said the scoutmaster. "Heroic duty done for one's country will wipe out a lot of faults.—It's hard to get a line on Tom's thoughts. He asked me the other day what I thought about the saying, To do a great right, do a little wrong. I don't know where he rooted it out, but it gave me a shudder when he asked me."

"He was standing in front of the recruiting station down at the postoffice yesterday," said Roy, "staring at the posters. Goodness only11 knows what he was thinking about. He came along with me when he saw me."

"Hmmm," said Mr. Ellsworth thoughtfully.

"But I guess he wouldn't try anything like that here—the town is too small," said Roy. "Even the recruiting fellow knows him."

"Yes; but what worries me," said Mr. Ellsworth, "is when he goes to the city and stands around listening to the orators and watches the young fellows surging into the recruiting places. That phrase, Your country needs you, is dinging in his ears."

"He'd get through in a walk," said Roy.

"That's just the trouble," Mr. Ellsworth mused. "Tom would never do anything that he thought wrong," he added, after a pause; "but he has a way of doping things out for himself, and sometimes he asks queer questions."

"Well, he promised you, anyway," said Roy finally.

"Oh, yes, that settles it," Mr. Ellsworth said. "All's well that ends well."

"We should worry," said Roy, in his usual light-hearted manner.

"That's just what I shan't do," the scoutmaster answered.12

"All right, so long, see you later," Roy called, as he started up Blakeley's hill.

Mr. Ellsworth and Pee-wee waved him goodnight. Presently Pee-wee deserted and went down, scout pace, through Main Street, laboriously hoisting his belt axe up with every other step. It was very heavy and a great nuisance to his favorite gait, but he had worn it regularly to scout meeting ever since war had been declared.

CHAPTER II

"BULL HEAD" AND "BUTTER FINGERS"

The lateness of the hour did not incline Tom to hurry on his journey homeward. He was thoroughly discouraged and dissatisfied with himself, and it pleased his mood to amble along kicking a stone in front of him until he lost it in the darkness. Without this vent to his distemper he became still more sullen. It would have been better if he had hunted up the stone and gone on kicking it. But now he was angry at the stone too. He was angry at everybody and everything.

Ever since war had been declared Tom had worked with the troop, doing his bit under Mr. Ellsworth's supervision, and everything he had done he had done wrong—in his own estimation.

The Red Cross bandages which he had rolled had had to be rolled over again. The seeds which he had planted had not come up, because he had buried them instead of planting them. Roy's onion plants were peeping coyly forth in14 the troop's patriotic garden; Doc Carson's lettuce was showing the proper spirit; a little regiment of humble radishes was mobilizing under the loving care of Connie Bennett, and Pee-wee's tomatoes were bold with flaunting blossoms. A bashful cucumber which basked unobtrusively in the wetness of the ice-box outlet under the shed at Artie Van Arlen's home was growing apace. But not a sign was there of Tom's beans or peas or beets—nothing in his little allotted patch but a lonely plantain which he had carefully nursed until Pee-wee had told him the bitter truth—that this child of his heart was nothing but a vulgar weed.

It is true that Roy Blakeley had tried to comfort Tom by telling him that if his seeds did not come up in Bridgeboro they might come up in China, for they were as near to one place as the other! Tom had not been comforted.

His most notable failure, however, had come this very week when three hundred formidable hickory sticks had been received by the Home Defense League and turned over to the Scouts to have holes bored through them for the leather thongs.

There had been a special scout meeting for this15 work; every scout had come equipped with a gimlet, and there was such a boring seance as had never been known before. Roy had said it was a great bore. As fast as the holes were bored, Pee-wee had tied the strips of leather through them, and the whole job had been finished in the one evening.

Tom had broken his gimlet and three extra ones which fortunately some one had brought. The hickory had proven as stubborn as he was himself—which is saying a great deal.

He had tried boring from each side so that the holes would meet in the middle; but the holes never met. When he had bored all the way through from one side, he had either broken the gimlet or the hole had come slantingways and the gimlet had come out, like a woodchuck in his burrow, where it had least been expected to appear.

And now, to cap the climax, he was to stand outside one of the registration places the next day and pin little flags on the young men as they came out after registering. The other members of the troop were to be distributed all through the county for this purpose (wherever there was no local scout troop), and each scout, or group of scouts, would sally heroically forth in the morning16 armed with a shoebox full of these honorable mementoes, made by the girls of Bridgeboro.

And meanwhile, thought Tom, the Germans were sinking our ships and dropping bombs on hospitals and hitting below the belt, generally. He was not at all satisfied with himself, or with his trifling, ineffective part in the great war. He felt that he had made a bungle of everything so far, and his mind turned contemptuously from these inglorious duties in which he had been engaged to the more heroic rôle of the real soldier.

Perhaps his long trousers had had something to do with his dissatisfaction; in any event, they made his bungling seem the more ridiculous. His fellow scouts had called him "bull head" and "butter fingers," but only in good humor and because they loved to jolly him; for in plain fact they all knew and admitted that Tom Slade, former hoodlum, was the best all-round scout that ever raised his hand and promised to do his duty to God and Country and to obey the Scout Law.

The fact was that Tom was clumsy and rough—perhaps a little uncouth—and he could do big things but not little things.

As he ambled along the dark street, nursing his disgruntled mood, he came to Rockwood Place17 and turned into it, though it did not afford him the shortest way home. But in his sullen mood one street was as good as another, and Rockwood Place had that fascination for him which wealth and luxury always had for poor Tom.

Three years before, when Tom Slade, hoodlum, had been deserted by his wretched, drunken father and left a waif in Bridgeboro, Mr. Ellsworth had taken him in hand, Roy had become his friend, and John Temple, president of the Bridgeboro Bank, noticing his amazing reformation, had become interested in him and in the Boy Scouts as well.

It had proven a fine thing for Tom and for the Scouts. Mr. Temple had endowed a large scout camp in the Catskills, which had become a vacation spot for troops from far and near, and which, during the two past summers, had been the scene of many lively adventures for the Bridgeboro boys.

But Tom had to thank Temple Camp and its benevolent founder for something more than health and recreation and good times. When the troop had returned from that delightful woodland community in the preceding autumn and Tom had reached the dignity of long trousers, the question18 of what he should do weighed somewhat heavily on Mr. Ellsworth's mind, for Tom was through school and it was necessary that he be established in some sort of home and in some form of work which would enable him to pay his way.

Perhaps Tom's own realization of this had its part in inclining him to go off to war. In any event, Mr. Ellsworth's perplexities, and to some extent his anxieties, had come to an end when Mr. Temple had announced that Temple Camp was to have a city office and a paid manager for the conduct of its affairs, which had theretofore been looked after by himself and the several trustees and, to some extent, by Jeb Rushmore, former scout and plainsman, who made his home at the camp and was called its manager.

Whether Jeb had fulfilled all the routine requirements may be a question, but he was the spirit of the camp, the idol of every boy who visited it, and it was altogether fitting that he should be relieved of the prosy duties of record-keeping which were now to be relegated to the little office in Mr. Temple's big bank building in Bridgeboro.

So it was arranged that Tom should work as a19 sort of assistant to Mr. Burton in the Temple Camp office and, like Jeb Rushmore, if he fell short in some ways (he couldn't touch a piece of carbon paper without getting his fingers smeared) he more than made up in others, for he knew the camp thoroughly, he could describe the accommodations of every cabin, and tell you every by-path for miles around, and his knowledge of the place showed in every letter that went out over Mr. Burton's name.

From the window, high up on the ninth floor, Tom could look down behind the big granite bank building upon a narrow, muddy place with barrel staves for a sidewalk and tenements with conspicuous fire escapes, and washes hanging on the disorderly roofs. This was Barrel Alley, where Tom had lived and where his poor, weary mother had died. He could pick out the very tenement. Strangely enough, this spot of squalor and unhappy memories held a certain place in his affection even now.

Tom and Mr. Burton and Miss Ellison, the stenographer, were the only occupants of the little office, but Mr. Temple usually came upstairs from the bank each day to confer with Mr. Burton for half an hour or so.20

There was also another visitor who was in the habit of coming upstairs from the bank and spending many half hours lolling about and chatting. This was Roscoe Bent, a young fellow who was assistant something-or-other in the bank and whose fashionable attire and worldly wisdom caused Tom to stand in great awe of him.

Roscoe made no secret of the fact that he came up in order to smoke cigarettes, which practice was forbidden down in the bank. He would come up, smoke a cigarette, chat a while, and then go down again. He seemed to know by inspiration when Mr. Burton and Mr. Temple were going to be there. Up to the morning of this very day he had never shown very much interest in either Tom or Temple Camp, though he appeared to entertain a lively interest in Miss Ellison, and Tom envied him his easy manner and his faculty for entertaining her and making her laugh.

On the morning of this day, however, when he had come up for his clandestine smoke, he had manifested much curiosity about the camp, looking over the maps and pictures and asking many questions.

Tom had felt highly flattered.

CHAPTER III

ROSCOE BENT

Indeed, Tom had felt so highly flattered that the memory of young Mr. Roscoe Bent's condescension had lingered with him all day, and now he was going to give himself the pleasure of walking through Rockwood Place for a passing glimpse of the beautiful house wherein young Roscoe resided.

Tom knew well enough that Roscoe had to thank the friendship between his father and Mr. Temple for his position in the bank. In his heart he knew that there was not much to be said for Roscoe; that he could do many things which Roscoe couldn't begin to do; but Roscoe on the other hand could do all those little things which poor Tom never could master; he could joke and make people laugh, and he always knew what to say and how to say it—especially to girls.

Tom's long trousers had not brought him this accomplishment, and in his clumsiness of speech22 and manner he envied this sprightly youth who had become so much of a celebrity in his thoughts that he actually took a certain pleasure in walking past the Bent residence just because it was where Roscoe and his well-to-do parents lived.

He was a little ashamed of doing this, just as he was ashamed of his admiration for Roscoe, and he knew that neither Roscoe, with his fine airs, nor Roscoe's home would have had any attractions for Roy at all. But then Roy's father was rich, whereas Tom's father had been poor, and he had come out of the slums and in some ways he would never change.

"He isn't so bad, anyway," Tom muttered to himself, as he kicked another stone along. "I knew he'd be really interested some day. Any feller's got to be interested in a camp like that. If he only went there once, he'd see what it was like and he'd fall for it, all right. I bet in the summer he goes to places where they dance and bow, and all that, but he'd fall for Temple Camp if he ever went there—he would."

Tom was greatly elated at Roscoe's sudden interest, and he believed that great things would come of it.23

"If he could only once see that shack up on the mountain," he said to himself, "and make that climb, I bet he'd knock off his cigarettes. If he thought those pictures were good—gee, what would he think of the shack itself!"

When he reached the Bent house he was surprised to see an automobile standing directly in front of it which he had not noticed as he approached because its lights were out. Not even the little red light which should have illuminated the car's number was visible, nor was there a single light either in the entrance hall or in any of the windows of the big house.

In the car sat a dark figure in the chauffeur's place, and Tom, as he passed, fancied that this person turned away from him. He was rather surprised, and perhaps a little curious, for he knew that the Bents did not keep a car, and he thought that if the presence of the machine meant visitors, or a doctor, there would be some light in the house.

Reaching the corner, he looked back just in time to see another figure, carrying luggage, descend the steps and enter the car. He was still close enough to know that not a word was spoken nor a sound made; there was not even the familiar24 and usual bang of the automobile door. But a certain characteristic swing of the person with the luggage, as he passed one bag and then the other into the car, showed Tom that the figure was that of young Roscoe Bent. Then the car rolled away, leaving him gaping and speculating in the concealment of a doorway near the corner.

"I wonder where he can be going this time of night," Tom mused. "Gee, that was funny! If he was going on a vacation or anything like that, he'd have said so this morning—and he'd have said good-bye to me. Anyway, he'd have said good-bye to Miss Ellison...."

Tom boarded with a private family in Culver Street, and after he reached home he sat up in his room for a while working with a kind of sullen resignation on the few registration badges which had still to have pins attached to them.

It was while he was engaged in this heroic labor that a thought entered his mind which he put away from him, but which kept recurring again and again, and which ended by cheating him out of his night's sleep. Why should Roscoe Bent be leaving home with two suitcases at twelve o'clock at night when he would have to register for the selective draft the next day?25

After this rather puzzling question had entered his mind and refused to be ousted or explained away, other puzzling questions began to follow it. Why had the lights of the automobile been out? Why had there been no lights in the house? Why had no one come out on the porch to bid Roscoe good-bye? Why had not Roscoe slammed the auto door shut, as one naturally did, that being the easiest way to shut it?

Well, all that was Roscoe's business, not his, thought Tom, as he settled down to go to sleep, and perhaps he had closed the door quietly because he wished not to disturb any one so late at night. That was very thoughtful of Roscoe....

But just the same Tom could not go to sleep, and he lay in bed thinking uneasily.

He had just about conquered his misgivings and had begun to think how suspicious and ungenerous he was, when another question occurred to him which had the effect of a knockout blow to his peace of mind.

Why had Roscoe Bent told Miss Ellison that it was better to be a live coward than a dead hero?

—Why, he had only been joking, of course, when he said that! It was one of those silly, careless26 things that he was always saying. Miss Ellison had not seemed to think it was very funny, but that had only made Roscoe laugh the more. "I'd rather kill time than kill Germans," he had said lightly. And Miss Ellison had said, "You're quite brave at killing time, aren't you?"

It was just joking and jollying, thought Tom, as he turned over for the fourth or fifth time, and he wished that he could joke and jolly like that. He made up his mind that when Roscoe came upstairs in the morning he would ask him whether the Germans weren't cowards to murder innocent women and children, and whether he would really want to be like them. He believed he could say that much without a tremor, even in front of Miss Ellison.

He wished morning would come so that he could be sure that Roscoe ... so that he could say that when Roscoe came upstairs.

"I'll bet he'll be sleepy after being out so late," thought Tom.

CHAPTER IV

THE CUP OF JOY

Tom was to have the next day off for his patriotic activities, but he went to the Temple Camp office early in the morning to get the mail opened and attend to one or two routine duties.

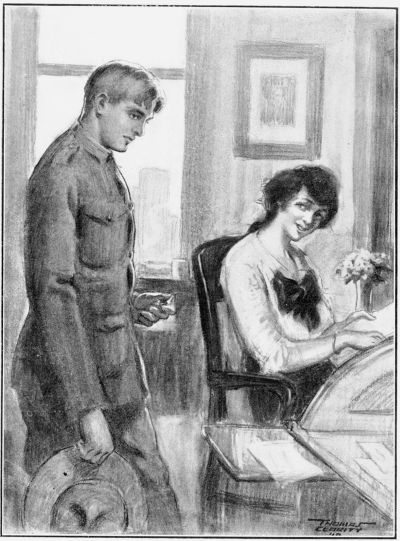

He found Miss Ellison already at her desk, and she greeted him with a mysterious smile.

"I hear you're going to be one of the celebrities," she said, busying herself with her typewriter machine.

"One of the what?" said Tom.

"One of the leading figures of the day. I don't suppose you'll even look at poor me to-morrow.—I was down in the bank and Mr. Temple said to send you down as soon as you came in."

"Me?" stammered Tom.

"Yes, you."

For a few seconds Tom waited, not knowing what to say or do—especially with his feet.28

"You didn't notice if Roscoe was down there, did you?" he finally ventured.

"I most certainly did not," answered Miss Ellison, smiling with that same mysterious smile, as she tidied up her desk. "I have something else to think of besides Mr. Roscoe Bent."

Tom shifted from one foot to the other. "I thought you—maybe—kind of—I thought you liked him," said he.

"Oh, did you?"

He had never been quite so close to Miss Ellison before, nor engaged in such familiar discourse with her. He hesitated, moving uneasily, then made a bold plunge.

"I think you can—I think a person—I think a feller can tell if a girl kind of likes a certain feller—sort of——"

"Indeed!" she laughed. "Well, then, perhaps you can tell if I like you—sort of."

This was too much for Tom. He wrestled for a moment with his embarrassment, but he was in for it now, and he was not going to back out.

"I'm too clumsy for girls," said he; "they always notice that."

"You seem to know all about them," said the girl; "suppose I should tell you that I never noticed29 any such thing.—A girl usually notices if a fellow is strong, though," she added.

"It was being a scout that made me strong."

"There are different ways of being strong," observed Miss Ellison, busying herself the while.

"I know what you mean," said Tom. "I got a good muscle."

She leaned back in her chair and looked at him frankly. "I didn't mean exactly that," she said. "I meant if you make up your mind to do a thing, you'll do it."

Again Tom waited, not knowing what to say. He felt strangely happy, yet very uncomfortable. At length, for lack of anything better to say, he observed:

"I guess you kinder like Roscoe, all right."

For answer she bent over her typewriter and began to make an erasure.

"Don't you?" he persisted, gaining courage.

"Do I have to tell you?" she asked, laughing merrily.

Tom lingered for a few moments. He wanted to stay longer. This little familiar chat was a bigger innovation in his life than the long trousers had been. His heart was pounding just as it had pounded when he first took the scout oath. Evidently30 the girl meant to leave early herself, and see something of the day's festivities, for she was very prettily attired. Perhaps this, perhaps the balmy fragrance of that wonderful spring day which Providence had ordered for the registration of Uncle Sam's young manhood, perhaps the feeling that some good news awaited him down in Mr. Temple's office, or perhaps all three things contributed to give Tom a feeling of buoyancy.

"Are you going to see the parade?" he asked. "I got a badge here maybe you'd like to wear. I can get another for myself."

"I would like very much to wear it," she said, taking the little patriotic emblem which he removed from his khaki coat. "Thank you."

Tom almost hoped she would suggest that he pin it on for her. He stood for a few moments longer and then, as he could think of nothing more to say, moved rather awkwardly toward the door.

"You look splendid to-day, Tom," Miss Ellison said. "You look like a real soldier in your khaki."

"The woman where I board pressed it for me yesterday," he said, blushing.

"It looks very nice."

Tom went down in the elevator, and when it31 stopped rather suddenly at the ground floor it gave him exactly the same feeling that he had experienced while he talked to Miss Ellison....

Roscoe Bent was not at his desk as he passed the teller's window and glanced through it, but he did not think much of that, for it was early in the day and the sprightly Roscoe might be in any one of a dozen places thereabout. He might be up in the Temple Camp office, even.

John Temple, founder of Temple Camp and president of the bank, sat at his sumptuous desk in his sumptuous office and motioned Tom to one of the big leather chairs, the luxuriousness of which disconcerted him almost as much as had Miss Ellison's friendliness.

"I told Margaret to send you down as soon as you came in, Tom," said Mr. Temple, as he opened his mail. "I want to get this matter off my mind before I forget it. You know that General Merrill is going to be here to-night, I suppose?"

"I heard the committee was trying to get him."

"Well, they've got him, and the governor's going to be here, too; did you hear that?"

"No, sir, I didn't," said Tom, surprised.

"I've just got word from his secretary that he32 can spend an hour in our little berg and say a few words at the meeting to-night. Now listen carefully, my boy, for I've only a few minutes to talk to you. This thing necessitates some eleventh-hour preparation. The plan is to have a member from every local organization in town to form a committee to receive the governor and the general. That's about all there is to it.

"There's the Board of Trade, and the Community Council, and—let's see—the churches and the Home Defense and the Red Cross and the Daughters of Liberty and the Citizens' Club, and the Boy Scouts."

Already Tom felt flattered.

"Each of these organizations has designated one of its members to act on the committee. I had Mr. Ellsworth on the phone this morning and told him he'd have to represent the scouts. He said he'd do no such thing—that he wasn't a boy scout."

"He's the best scout of all of us," said Tom.

"He says you're the best," retorted Mr. Temple; "so there you are."

"Roy's got twice as many merit badges as I have," said Tom.

"Well, you've got long trousers, anyway," said33 Mr. Temple, "and Mr. Ellsworth says you're the representative scout, so I guess you're in for it."

"M-me?"

"Now, pay attention. You're to knock off work at the registration places at five o'clock and go up to the Community Council rooms, where you'll meet these ladies and gentlemen who are to form the reception committee. Reverend Doctor Wade will be looking for you, and he'll take you in hand and tell you just what to do. There won't be much. I think the idea is to meet the governor and the general with automobiles and escort them up to the Lyceum. The committee'll sit on the platform, I suppose. Doctor Wade will probably do all the talking.... You're not timid about it, are you?" he added, looking up and smiling.

"Kind of, but——"

"Oh, nonsense; you just do what the others do. Here—here's a reception committee badge for you to wear. This is one of the burdens of being a public character, Tom," he added slyly. "Mr. Ellsworth's right, no doubt; if the scouts are to be represented at all they should be represented by a scout. Don't be nervous; just do as the others do, and you'll get away with it all right.34 Now run along. I suppose I'll be on the platform too, so I'll see you there.... You look pretty nifty," he added pleasantly, as Tom took the ribbon badge.

"Mrs. Culver pressed it for me," said Tom. "It had a stain, but she got it off with gasoline."

"Good for her."

"Would—do you think it would be all right to wear my Gold Cross?"

"You bet!" said Mr. Temple, busy with his mail. "If I had the scouts' Gold Cross for life-saving, I'd wear it, and I'd have an electric light next to it, like the tail light on an automobile to show the license number."

Tom laughed. He found it easy to laugh. He was nervous, almost to the point of panic, but his heart was dancing with joy.

"All right, my boy," laughed Mr. Temple. "Go along now, and good luck to you."

As Tom went out of Mr. Temple's office he seemed to move on wings. He was half frightened, but happy as he had never been in all his life. His cup of joy was overflowing. He had been through the ordeal of more than one generous ovation from his comrades in the troop; he had stood awkward and stolid with that characteristic35 frown of his while receiving the precious Gold Cross which this night he would wear.

But this was different—oh, so different! He, Tom Slade, was to help receive the governor of the state and one of Uncle Sam's famous generals. The Boy Scouts were to be represented because the Boy Scouts had to be reckoned with on these occasions, and he, Tom Slade, organizer of the Elk Patrol and now assistant to the scoutmaster, was chosen for this honor.

"I'm glad I had my suit pressed," he thought.

What a day it had been for him so far! He had had a little chat with Margaret Ellison, she had said she liked him—anyway, she had almost said it, and she had taken the little emblem from him and had said that if he made up his mind to do a thing he would do it. He remembered the very words. Then he had gone downstairs and received this overwhelming news from Mr. Temple. What if he had planted his seeds wrong and bored holes slantingways instead of straight? He was so proud and happy now that he added the official, patented scout smile to his sumptuous regalia and smiled all over his face.

He was usually rather timid about speaking to the men in the bank unless they spoke to him first,36 for the bank was an awesome place to him; but to-day he was not afraid, and his recollection of the pleasant little chat upstairs reminded him of a fine thing to do.

"Is Rossie Bent here?" he asked, stopping at the teller's cage.

"Bent!" called the teller.

Tom waited in suspense.

"Not here," called a voice from somewhere beyond.

"Not here," repeated the teller, and added: "Asleep at the switch, I dare say."

Evidently the people of the bank had Roscoe's number. A strange feeling came over Tom which chilled his elation and troubled him. Irresistibly there rose in his mind a picture of a waiting automobile, of a dark figure, and a silent departure late at night.

"I guess maybe he's just stopped to register, hey?" said Tom.

"Stopped for something or other, evidently," said the teller.

"Could I speak to Mr. Temple's secretary?" Tom asked.

Mr. Temple's secretary, a brisk little man, came out, greeting Tom pleasantly.37

"Congratulations," said he.

"I meant to ask Mr. Temple if I could have a couple of reserved seat tickets for the patriotic meeting to-night," said Tom, "but I was kind of flustered and forgot about it. I could get them later, I guess, but if you have any here I'd like to get a couple now because I want to give them to some one."

"Yes, sir," said the secretary, in genial acquiescence; "just a minute."

Tom went up in the elevator holding the two tickets in his hand. If his joy was darkened by any growing shadow of apprehension, he put the unpleasant thought away from him. He was too generous to harbor it; yet a feeling of uneasiness beset him.

As he entered the office, Margaret Ellison, smiled broadly.

"You knew what it was?" he said boldly.

"Certainly I knew, and isn't it splendid!"

"I got two tickets," said Tom, "for reserved seats down front. They're in the third row. I was going to give them to Roscoe and tell him to take—to ask you to go. But he's—he's late—I guess he stopped to register. So I'll give them38 to you, and when he comes up you can tell him about it."

"I'll give them to him and say you asked me to."

"All right," Tom said hesitatingly; "then he'll ask you."

"Perhaps."

She disappeared into the little inner office where Mr. Burton was waiting to dictate his mail, and Tom strolled over to the big window which overlooked Barrel Alley and gazed down upon that familiar, sordid place.

It was a long road from that squalid tenement down there to a place on the committee which was to receive the governor of the state. Over there to the left, next to Barrey's junk shop, was poor Ching Wo's laundry, into which Tom had hurled muddy barrel staves. And that brick house with the broken window was where "Slats" Corbett, former lieutenant of Tom's gang, had lived.

A big lump came up in his throat as he thought over the whole business now and of where the scout trail had brought him. Oh, he was happy!

The bright spring sunshine which poured in through the window on that wonderful morning, the flags which waved happyly here and there,39 seemed to reflect his own joy, and he was overwhelmed with the sense of triumph.

"That was a good trail I hit, all right," he said to himself. He could not have said it out loud without his voice breaking.

One thing he wished in those few minutes of exultation. He wished that his mother might be there to see him on the stage, a conspicuous part of that patriotic demonstration, with the Gold Cross of the scouts upon his left breast. That would make the cup of joy overflow.

But since that could not be, the next best thing would be the knowledge that Margaret Ellison would be sitting there in the third row, looking ever so pretty, and would see him, and notice the Gold Cross and wonder what it meant.

"I'm glad I never wore it to the office," he mused.

And Roscoe Bent, with all his sprightly manners and fine airs, would see where this good scout trail, which he had ridiculed, had brought Tom.

"It's a bully—old—trail—it is," he said to himself; "it's one good old trail, all right."

He took out his handkerchief and rubbed his eyes. Perhaps the bright sunlight was too strong for them.

CHAPTER V

THE MAIN TRAIL

But a trail is a funny thing. It is full of surprises and hard to follow. For one thing, you can never tell just where it is going to bring you out. There is the main trail and there are branch trails, and it is often puzzling to determine which is the main trail and which the branch.

Yet you must determine this somehow, for the one may lead you to food and shelter, to triumph and honor perhaps; while the other, which may be ever so clear and inviting, will lead you into bog and mire; so you have to be careful.

Of one thing you may be certain: there are not often two trails to the same place. You must pick one branch or the other. You must know where you want to go, and then hit the right trail. You must not be fooled by a side trail just because it happens to be broad and easy and pleasant. There are ways of telling which is the right trail, and you must learn those ways; otherwise you are not a good scout.41

Upon the sleeve of Tom Slade's khaki jacket was seen the profile of an Indian. It was the scouts' merit badge for pathfinding. It meant that he knew every trail and byway for miles about Temple Camp. It meant that he had picked his way where there was no trail, through a dense and tangled wilderness; that he had found his way by night to a deserted hunting shack on the summit of a lonely wooded mountain in the neighborhood of Temple Camp and that he had later blazed a trail to that isolated spot.

Even Rossie Bent had opened his eyes at Tom's simple, unboastful narrative of this exploit, and had followed Tom's finger on the office map as he traced that blazed trail from the wood's edge near the camp up through the forest and along the brook to the very summit of the frowning height, from which the nickering lights of Temple Camp could be seen in the distance.

"I'll bet not many people go up there," Roscoe had said.

So it was natural that when Tom looked back and thought of his career as a scout, of his rise from squalor and vicious mischief to this level of manliness and deserved honor, he should think of it as a trail—a good scout trail which he had42 picked up and followed. Down there in the mud of Barrel Alley it had begun, and see where it had led! To the platform of the Bridgeboro Lyceum where he, Tom Slade, would wear his Gold Cross, which every citizen at that patriotic Registration Day celebration might see, and would represent the First Bridgeboro Troop, B. S. A. in the town's welcome to the governor!

Oh, he was happy!

"It's good I didn't listen to Slats Corbett and Sweet Caporal," he mused. "I hit the right trail, all right. I bet if——"

The door opened suddenly, and Mr. Brown from the bank entered with another gentleman, who appeared greatly disturbed.

"Has Rossie Bent been up here to-day?" Mr. Brown asked.

"No, sir," said Tom. He felt his own voice tremble a little, and he realized that something was wrong.

"This is Mr. Bent," said Mr. Brown, "Roscoe's father. Roscoe hasn't been seen since last night, and his father is rather concerned about him."

"You haven't seen him—to-day?" Mr. Bent asked anxiously.43

"No, sir," said Tom.

The two men looked soberly at each other, and Tom went over to the door of the private office, which stood ajar, and quietly closed it.

"Mr. Burton is busy," he said.

"We might ask him," Mr. Brown suggested.

For the space of a few seconds Tom stood uneasily trying to muster the courage to speak.

"It—it wouldn't be any good to let a lot of people know," he said hesitatingly, but looking straight at Roscoe's father. "Mr. Burton only got here a few minutes ago, and he couldn't tell anything.—If you spoke to him, Miss Ellison would know about it too."

He spoke with great difficulty and not without a tremor in his voice, but his meaning reached the troubled father, who nodded as if he understood.

"It's early yet," Tom ventured; "maybe he'll think it over, kind of, and—and——"

"Thank you, my boy," said Mr. Bent soberly.

The two men stood a moment, as if not knowing what to do next. Then they left, and Tom remained standing just where he was. Of course, he was not surprised, only shocked.

"I knew it all the time," he said to himself, "only I wouldn't admit it."44

He had been too generous to face the ugly fact. To him, who wished to go to war, the very thought of slacking and cowardice seemed preposterous—impossible.

"I was just kidding myself," he said, with his usual blunt honesty, but with a wistful note of disappointment. "There's no use trying to kid yourself—there ain't."

Mr. Burton came out with his usual smiling briskness and greeted Tom pleasantly. "Congratulations, Tommy," said he. "I suppose I'll see you among the big guns to-night. You leaving soon?"

"Y-yes, sir, in a few minutes."

"Miss Ellison and I are so unpatriotic that we're going to work till the parade begins this afternoon."

"I don't suppose he'll even notice us to-morrow," teased the girl, "he'll be so proud."

Tom smiled uncomfortably and wandered over to the window where, but a few minutes before, he had looked out with such pride and happiness. He did not feel very happy now.

Close by him was a table on which were strewn photographs of Temple Camp and the adjacent lake, a few birch bark ornaments, carved canes,45 and other specimens of handiwork which scouts had made there. There was also a large portfolio with plans of the cabins and pavilion and rough charts and diagrams of the locality.

Tom had shown this portfolio to many callers—scoutmasters and parents of scouts—who had come to make inquiries about the woodland community. He had shown it to Roscoe Bent only the day before and, as we know, he had been greatly pleased at the lively interest which that worldly young gentleman had shown.

He opened the portfolio idly now, and as he did so his gaze fell upon the map which showed the wooded hill and the position of the lonesome shack upon its summit. He called to mind with what pride he had traced his own blazed path up through the forest and how Roscoe had followed him, plying him with questions.

Then, suddenly, like a bolt out of the sky, there flashed into Tom's mind a suspicion which, but for his generous, unsuspecting nature, he might have had before. Was that why Roscoe Bent had been so interested in the little hunting shack on the mountain? Was that why he had asked if any one ever went up there; why he had inquired if there were fish to be caught in the brook and game46 to be hunted in the neighborhood? Was that why he had been so particular about the blazed path, and whether there was a fireplace in or near the shack? Had he been thinking of it as a safe refuge, a place of concealment for a person who had shirked his duty?

"He could never live there," said Tom; "he could never even get there."

As the certainty grew in his mind, he was a little chagrined at his own credibility, but he was more ashamed for Roscoe.

"I might have known," he said, "that he wasn't really interested in camping.... He's a fool to think he can do that."

To Tom, who longed to go to war and who was deterred only by his promise to Mr. Ellsworth, the extremity that Roscoe had evidently gone to in the effort to escape service seemed unbelievable. But that was his game, and Tom saw the whole thing now as plain as day. It made him almost sick to think of it. While he, Tom, would be handing badges to the throng of proud and lucky young men just fresh from registering, while he sat upon the platform and listened to the music and the speeches in their honor, Roscoe Bent would be tracing his lonely way up that distant47 mountain with the insane notion of camping there. He would try to cheat the government and disgrace his family.

"I don't see how he could do that—I don't," said Tom. "I wonder what his father would say if he knew.—I wonder what Miss Ellison would say. I wonder what his mother would think."

He looked down again into Barrel Alley, and fixed his eyes upon the tenement where he and his poor mother and his wretched father had lived. But he was not thinking of his mother now—he was thinking of Roscoe Bent's mother and of his troubled father, going from place to place and searching in vain for his fugitive son.

"If I told him," thought Tom, "it would queer Roscoe. It wouldn't do for anybody to know.... I just got to go and bring him back.... Maybe they'd let him register to-morrow. He could say—he could say anything he wanted to about why he was away on the fifth of June. If he comes back they'll let him register, but if he doesn't they'll find him; they'll put his name in newspapers and lists and they'll find him. I just got to go and bring him back. And I got to go without telling anybody anything, too."

For a few moments longer he stood gazing out48 of the window down into that muddy alley where the good scout trail to honor and achievement had begun for him. For a few moments he thought of where it had brought him and of the joy and fulfillment which awaited him this very night. He wondered what people would say if he were not there. Well, in any event, they would not call him a slacker or a coward. He felt that there was no danger of being misjudged if he did his highest duty.

"It's kind of like a branch trail I got to follow," he said, his voice breaking a little. "I said it was a good trail, but now I see there's a branch trail that goes off, kind of, and I got to follow that...."

But, of course, it wasn't a branch trail at all—it was the main trail, the true scout trail, which, forgetting all else, he was resolved to follow.

CHAPTER VI

TOM AND THE GOLD CROSS

Mr. Ellsworth was right when he said that Tom had a way of doping things out for himself. He had picked up scouting without much help, and he seldom asked advice.

His duty was very clear to him now. As long as no one but himself and Roscoe knew about this miserable business, the mistake could be mended and no harm come of it.

The thing was so important that the smaller evil of neglecting his allotted task and foregoing the honors which awaited him did not press upon him at all. He was disappointed, of course, but he acknowledged no obligation to anybody now except to Roscoe Bent and those whom his disgrace would affect. Wrong or right, that is the way Tom's mind worked.

Quietly he took his hat and went out, softly closing the door behind him. For a second or two he waited in the hall. He could still hear the50 muffled sound of the typewriter machine in the office.

As he went down in the elevator he heard two gentlemen talking about the celebration that evening and about the governor's coming. Tom listened wistfully to their conversation.

He had already taken from his pocket (what he always carried as his heart's dearest treasure) a dilapidated bank book. He intended to draw ten dollars from his savings account, which would be enough to get him to Catskill Landing, the nearest railroad point to camp, and to pay the return fare for himself and Roscoe.

But the bank was closed and Tom was confronted by a large placard in the big glass doors:

CLOSED IN HONOR OF OUR BOYS.

DON'T FORGET THE PATRIOTIC RALLY TO-NIGHT. DO YOUR BIT!

YOU CAN CHEER IF YOU CAN'T REGISTER.

He had forgotten that the bank was to close early. Besides spoiling his plan, it reminded him that the town was turning out in gala fashion, and his thoughts turned again to the celebration in the evening.51

"I gotta keep in the right trail," he said doggedly, as he turned toward home.

He did not know what to do now, for he had less than a dollar in his pocket, and he was stubbornly resolved to take no one into his confidence. If he had the money, he could catch a train before noontime and reach the mountain by the middle of the afternoon. He would make a short cut from the railroad and not go up through Leeds or to Temple Camp at all.

As he walked along he noticed that the street was happy with bunting. In almost every shop window was a placard similar to the one in the bank. A large banner suspended across the street read:

DON'T FORGET THE RALLY IN HONOR OF OUR BOYS TO-NIGHT!

"I ain't likely to forget it," he muttered.

He wondered how Roscoe's father felt when he saw that banner and this thought strengthened his determination so that he ignored the patriotic reminders all about him, and plodded stolidly along, his square face set in a kind of sullen frown.

"It's being—with the Colors, just the same," he said, "only in another kind of way—sort of."52

As he turned into West Street he noticed on the big bulletin board outside the Methodist Church the words:

THE GOVERNOR WILL BE ON THE PLATFORM OUR BOYS WILL BE IN THE TRENCHES THE BOY SCOUTS ARE ON THE JOB AND DON'T YOU FORGET IT!

"They're a live bunch, that Methodist Troop, all right," commented Tom.

He raised his hand and gently lifted aside a great flag which hung so low over the sidewalk that he could not walk under it without stooping.

"Just the same, I can say I'm with the Colors," he repeated. "You can be with them even if—even if they ain't around——"

He had evidently hit on some plan, for he walked briskly now through Culver Street, his lips set tight, making his big mouth seem bigger still.

He entered the house quietly and went up to the little room which he occupied. It was very small, with a single iron bed, a chair, a walnut bureau, and a little table whereon lay his Scout Manual and the few books which he owned. Outside the53 window, on its pine stick, hung a stiff muslin flag which he had bought.

He unlocked the top bureau drawer and took out a tin lock-box. This box was his pride, and whenever he took it out he felt like a millionaire. He had gazed at it in the window of a stationery store for many weeks and then, one Saturday, he had gone in and bought it for a dollar and a half.

He sat on the edge of his bed now, with the box on his knees, and rummaged among its contents. There was the pocket flashlight his patrol had given him; there was the scout jack-knife which had been a present from Roy's sister; an Indian arrow-head that Jeb Rushmore had found; a memorandum of the birthday of his patrol, and the birthdays of its members, and a clipping from a local paper describing how Tom Slade had saved a scout's life at Temple Camp and won the Gold Cross.

From the bottom of this treasure chest he lifted out a plush box which he rubbed on his knee to get the dust off, and then opened it slowly, carefully. He never tired of doing this.

As he lifted the cover the sunlight poured down out of the blue, cloudless sky of that perfect day,54 streaming cheerily into the plain little room which was all the home Tom had, and fell upon the glittering medal, making it shine with a dazzling brightness.

Often when Tom read of the Iron Cross being awarded to a submarine commander, or a German spy, or a Zeppelin captain for some unspeakable deed, he would come home and look at his own precious Gold Cross of the Scouts and think what it meant—heroism, real heroism; bravery untainted; courage without any brutal motive; the courage that saves, not destroys.

He breathed upon the rich gold now (though it needed no polishing) and rubbed it with his handkerchief. Then he sat looking at it long and steadily. There, shining under his eyes, was the familiar design, the three-pointed sign of the scouts, with the American eagle superimposed upon it, as if Uncle Sam and the scouts were in close partnership.

Tom remembered that the Handbook, in describing the scout sign, referred to it as neither an arrow-head nor a fleur-de-lis, though resembling both, but as a modified form of the sign of the north on the mariner's compass.

"Maybe it's like a fleur-de-lis, so as to remind55 us of France, kind of," Tom said, as he rubbed the medal again, "and——"

Suddenly a thought flashed into his mind. "And it's pointing to the north, too! It's the compass sign of the north, and it tells me where to go, 'cause Temple Camp and that hill are north from here.... Gee, that's funny, when you come to think of it, how that Gold Cross can kind of remind you—of everything.... Now I know I got to do it.... Nobody could tell me what I ought to do, 'cause the Gold Cross has told me.... And it'll help me to ... it will...."

CHAPTER VII

THE TRAIL RUNS THROUGH A PESTILENT PLACE

If Tom had entertained any lingering misgivings as to his path of duty, he cast them from him now. If he had harbored any doubts as to his success, he banished them. Uncle Sam, poor bleeding, gallant France, and the voice of the scout, had all spoken to him out of the face of the wonderful Gold Cross, and he wanted no better authority than this for something which he must do in order to be off on his errand.

Cheerfully removing his holiday regalia, he donned a faded and mended khaki suit and a pair of worn trousers, and as he did so he gave a little rueful chuckle at the thought of poor Roscoe struggling with the tangled thicket in a regular suit of clothes and without any of the facilities that a scout would be sure to take.

He slipped on an old coat, into the pocket of which he put his flashlight, some matches in an airtight box, his scout knife and a little bottle of57 antiseptic. Thus equipped, he felt natural and at home, and he looked as if he meant business.

Putting the plush box into his pocket, he descended the stairs quietly and slipped into the street. He hurried now, for he wished to get into the city in time to catch the noon train for Catskill.

At the end of Culver Street he turned into Williams Avenue and hurried along through its din and turmoil, and past its tawdry shops until he came to one which he had not seen in many a day. The sight of its dirty window, filled with a disorderly assortment of familiar articles, took him back to the old life in Barrel Alley and the days when his good-for-nothing father had sent him down here with odds and ends of clothing to be turned into money for supper or breakfast.

It spoke well for the self-respect which Tom had gained that he walked past this place several times before he could muster the courage to enter. When he did enter, the old familiar, musty smell and the sordid litter of the shelves renewed his unhappy memories.

"I have to get some money," he said, laying the plush case on the counter. "I have to get five dollars."58

He knew from rueful experience that one can seldom get as much as he wants in such a place, and five dollars would at least get him to his destination. Surely, he thought, Roscoe would have some money.

There were a few seconds of dreadful suspense while the man took the precious Gold Cross over to the window and scrutinized it.

"Three," he said, coming back to the counter.

"I got to have five," said Tom.

The man shook his head. "Three," he repeated.

"I got to have five," Tom insisted. "I'm going to get it back soon."

The man hesitated, and looked at him keenly. "All right, five," he said reluctantly.

Tom's hand almost trembled as he emerged into the bright sunlight, thrusting the ticket into a pocket which he seldom used. He had not examined it, and he did not wish to read it or be reminded of it. He felt ashamed, almost degraded; but he was satisfied that he had done the right thing.

"I thought that trail made a bee-line for the platform in the Lyceum," he said to himself, as he folded his five-dollar bill. "Gee, it's a funny59 thing; you never know where it's going to take you!"

And you never know who or what is going to cross your trail, either, for scarcely had he descended the steps of that stuffy den when whom should he see staring at him from directly across the street but Worry Benson and Will McAdam, of the other local scout troop.

They were evidently bent on some patriotic duty when they paused in surprise at seeing him, for they had with them a big flag pole and several bundles which looked as if they might contain printed matter.

Tom thought that perhaps these were a rush order of programs for the patriotic rally, and he wondered if they might possibly contain his name—printed in type.

But he thrust the thought away from him and, clutching his five dollars in his pocket, he turned down the street and started along the good scout trail.

CHAPTER VIII

AN ACCIDENT

The latter part of the afternoon found Tom many miles from Bridgeboro, and the trail which had passed through such sordid and pride-racking surroundings back in his home town, now led up through a quiet woodland, where there was no sound but the singing of the birds and an occasional rustle or breaking of a twig as some startled wild creature hurried to shelter.

Through the intertwined foliage overhead Tom could catch little glints of the blue sky, and once, when he climbed a tree to get his bearings, he could see, far in the distance, the lake and the clearing of Temple Camp, and could even distinguish the flagpole.

But no flag flew from it, for the season had not yet begun; Jeb Rushmore was on a visit to his former "pals" in the West, and the camp was61 closed tight. Down there was where Tom had won the Gold Cross.

He would have liked to see a flag waving, for Bridgeboro, with all its patriotic fervor and bustle, seemed very far away now, and though he was in a country which he loved and which meant much to him, he would have been glad of some tangible reminder that he was, as he had told himself, with the Colors.

Tom had left the train at Catskill Landing and reached the hill by a circuitous, unfrequented route, hoping to reach, before dark, the clearer path which he himself had made and blazed from the vicinity of Temple Camp to the little hunting shack upon the hill's summit. This, he felt sure, was the path Roscoe would follow.

It was almost dark when, having picked his way through a very jungle where there was no more sign of path than there is in the sky, he emerged upon the familiar trail at a point about a mile below the shack.

He was breathless from his tussle with the tangled underbrush, his old clothes had some fresh tears, and his hands were cut and bleeding.

For three solid hours he had worked his way up through the tangled forest, and now, as he62 reached the little trail which was not without its own obstacles, it seemed almost like a paved thoroughfare by contrast.

"Thank goodness!" he breathed. "It's good he didn't have to go that way—I—could see his finish!"

He was the scout now, the typical scout—determined, resourceful; and his tattered khaki jacket, his slouched hat, his rolled-up sleeves, and the belt axe which he carried in his hand, bespoke the rugged power and strong will of this young fellow who had trembled when Miss Margaret Ellison spoke pleasantly to him.

He sat down on a rock and poured some antiseptic over the scratches on his hands and arms.

"I can fight the woods, all right," he muttered, "even if they won't let me go off and fight the Germans."

After a few minutes' rest he hurried along the trail, pausing here and there and searching for any trifling sign which might indicate that the path had been recently traveled. Once his hopes of finding Roscoe were dashed by the discovery of a cobweb across the trail, but when he felt of it and found it sticky to the touch he knew that it had just been made.63

At last, hard though the ground was, he discovered a new footprint, and presently its meaning was confirmed when he caught a glint of light far ahead of him among the trees.

At the sight of it his heart gave a great bound. He knew now for a certainty that he was right. He had known it all along, but he was doubly assured of it now.

On the impulse he started to run, but his foot slipped upon an exposed root, and as he fell sprawling on the ground his head struck with a violent impact on a big stone.

After a few stunned seconds he dragged himself to a sitting posture; his head throbbed cruelly, and when he put his hand to his forehead he found that it was bleeding. He tried to stand, but when he placed his weight upon his left foot it gave him excruciating pain.

He sat down on the rock, dizzy and faint, holding his throbbing head and lifting his foot to ease, if possible, the agonizing pain.

"I'm all right," he muttered impatiently. "I was a fool to start running; I might have known I was too tired."

That was indeed the plain truth of the matter; he was so weary and spent that when, in the new64 assurance of success, he had begun to run, his tired feet had dragged and tripped him.

"That's what—you—get for—hurrying," he breathed heavily; "like Roy always said—more haste—less—— Ouch, my ankle!"

He tried again to stand, but the pain was too great, and his head swam so that he fell back on the rock.

"I wish Doc—Carson—was here," he managed to say. Doc was the troop's First-Aid Scout. "It—it was just—because I didn't—lift my feet—like Roy's always telling me—so clumsy!"

He soaked his handkerchief in antiseptic and bound it about his forehead, which was bleeding less profusely. After a few minutes, feeling less dizzy, he stood upon his feet, with a stoical disregard of the pain, determined to continue his journey if he possibly could.

The agony was excruciating, but he set his strong, thick lips tight, and, passing from one tree to another, with the aid of his hands, he managed to get along. More than once he stopped, clinging to a tree trunk, and raised his foot to ease the anguish. His head throbbed with a cruel, steady ache, and the faintness persisted so that often he65 felt he was about to reel, and only kept his feet by clinging to the trees.

"This—this is just about—the time I'd be going to that—racket——" he said. "Gee, but that foot hurts!"

He would have made a sorry figure on the platform. His old khaki jacket and trousers were almost in shreds. Bloodstains were all over his shirt. A great bloody scratch was visible upon his cheek. His hands were cut by brambles. There was a grim look on his dirty, scarred face. I am not so sure that he would have looked any nobler if he had been in the first-line trenches, fighting for Uncle Sam....

CHAPTER IX

ROSCOE JOINS THE COLORS

It was now nearly dark, and Tom worked his way along slowly, hobbling where there were no trees, and grateful for their support when he found them bordering the trail. His foot pained him exquisitely and he still felt weak and dizzy.

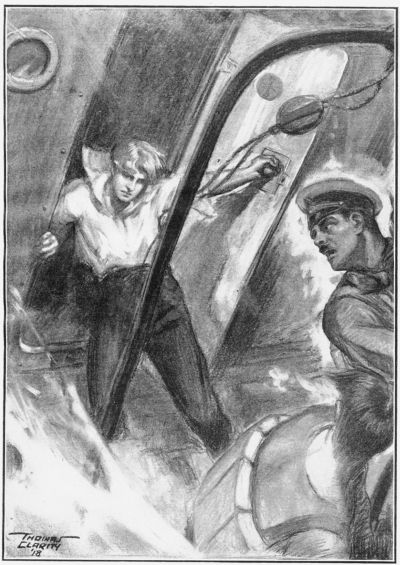

At last, after almost superhuman efforts, he brought himself within sight of the dark outline of the shack, which seemed more lonesome and isolated than ever before. He saw that the light was from a fire in the clearing near by, and a smaller light was discernible in the window of the shack itself.

Tom had always stood rather in awe of Roscoe Bent, as one of humble origin and simple ways is apt to feel toward those who live in a different world. And even now, in this altogether strange situation and with all the advantages both of right and courage on his side, he could not repress something of the same feeling, as he approached the little camp.

He dragged himself to within a few feet of the67 fire and stood clutching a tree and leaning against it as Roscoe Bent, evidently startled, came out and faced him.

A pathetic and ghastly figure Tom must have looked to the fugitive, who stood staring at him, lantern in hand, as if Tom were some ghostly scarecrow dropped from the clouds.

"It's me—Tom Slade," Tom panted. "You—needn't be scared."

Roscoe looked suspiciously about him and peered down the dark trail behind Tom.

"What are you doing here?" he demanded roughly. "Is anybody with you? Who'd you bring——"

"No, there ain't," said Tom, almost reeling. His weakness and the fear of collapsing before he could speak gave him courage, but he forgot the little speech which he had prepared, and poured out a torrent which completely swept away any little advantage of self-possession that Roscoe might have had.

"I didn't bring anybody!" he shouted weakly. "Do you think I'm a spy? Did you ever know a scout that was a sneak? Me and you—are all alone here. I knew you was here. I knew you'd68 come here, because you're crazy. I seen—saw—"

It was characteristic of Tom that on the infrequent occasions when he became angry, or his feelings got the better of him, he would fall into the old illiterate phraseology of Barrel Alley. He steadied himself against the tree now and tried to speak more calmly.

"D'you think just 'cause you jollied me and made a fool out of me in front of Miss Ellison that I wouldn't be a friend to you? Do you think"—he shouted, losing all control of himself—"that because I didn't know how to talk to you and—and—answer you—like—that I was a-scared of you? Did you think I couldn't find you easy enough? Maybe I'm—maybe I'm thick—but when I get on a trail—there's—there's nothin' can stop me. I got the strength ter strangle you—if I wanted to!" he fairly shrieked.

Then he subsided from sheer exhaustion.

Roscoe Bent had stood watching him as a man might watch a thunderstorm. "You hurt yourself," he said irrelevantly.

"It says in a paper," panted Tom, "that—that a man that's afraid to die ain't—fit to live. D'you think I'd leave—I'd let you—stay away and have people callin' you a coward and a—a slacker—and then somebody—those secret service fellows—come and get you? I wouldn't let them get69 you," he shouted, clutching the tree to steady himself, "'cause I know the trail, I do—I'm a scout—and I got here first—I——"

His hand slipped from the tree, he reeled and fell to the ground too quick for Roscoe to catch him.

"It's—it's all right," he muttered, as Roscoe bent over him. "I ain't hurt.... Roll your coat up tight—you'd know, if you was a scout—and put it under my neck. I—want a drink—of water.... You got to begin right now to-night, Rossie, with the Colors; you got to begin—by—by bein' a Red Cross nurse.... I'm goin' to call you Rossie now—like the fellers in the bank," he ended weakly, "'cause we're friends to each other—kind of."

CHAPTER X

TOM AND ROSCOE COME TO KNOW EACH OTHER

"I don't know what I said," said Tom; "I was kind of crazy, I guess."

"I guess I'm the one that was crazy," said Roscoe. "Does your head hurt now?"

"Nope. It's a good thick head, that's one sure thing. Once Roy Blakeley dropped his belt-axe on it around camp-fire, and he thought he must have killed me. But it didn't hurt much. Look out the coffee don't boil over."

Roscoe Bent looked at him curiously for a few seconds. It was early the next morning, and Tom, after sleeping fairly well in the one rough bunk in the shack, was sitting up and directing Roscoe, who was preparing breakfast out of the stores which he had brought.

"I guess that's why I didn't get wise when you first asked me about this place—'cause my head's so thick. Roy claimed he got a splinter from my head. He's awful funny, Roy is.... If I'd 'a' known in time," he added impassively, "I71 could 'a' started earlier and headed you off. I wouldn't 'a' had to stop to chop down trees."

"Why didn't you swim across the brook?" Roscoe asked. "All scouts swim, don't they?"

"Sure, but that's where Temple Camp gets its drinking water—from that brook; and every scout promised he wouldn't ever swim in it. It wasn't hard, chopping down the tree."

Roscoe gazed into Tom's almost expressionless face with a kind of puzzled look.

"It don't make any difference now," said Tom, "which way I came. Anyway, you couldn't of got back yesterday—before the places closed up. Maybe we've got to kind of know each other, sort of, being here like this. You got to camp with a feller if you want to really know him."

Roscoe Bent said nothing.

"As long as you get back to-day and register, it's all right," said Tom. "They'll let you.—It ain't none of my business what you tell 'em. You don't even have to tell me what you're going to tell 'em."

"I can't tell them I just ran away," said Roscoe dubiously.

"It's none of my business what you tell 'em," repeated Tom, "so long as you go back to-day72 and register. When you get it over with, it'll be all right," he added. "I know how it was—you just got rattled.... The first time I got lost in the woods I felt that way. All you got to do is to go back and say you want to register."

"I said I would, didn't I?" said Roscoe.

"Nobody'll ever know that I had anything to do with it," said Tom.

"Are you sure?" Roscoe asked doubtfully.

"They'd have to kill me before I'd tell," said Tom.

Roscoe looked at him again—at the frowning face and the big, tight-set mouth—and knew that this was true.

"How about you?" he asked. "What'll they think?"

"That don't make any difference," said Tom. "I ain't thinkin' of that. If you always do what you know is right, you needn't worry. You won't get misjudged. I've read that somewhere."

Roscoe, who knew more about the ways of the world than poor Tom did, shook his head dubiously. He served the coffee and some crackers and dry breakfast food of which he had brought a number of packages, and they ate of this makeshift repast as they continued their talk.73

"You ought to have brought bacon," said Tom. "You must never go camping without bacon—and egg powder. There's about twenty different things you can do with egg powder. If you'd brought flour, we could make some flapjacks."

"I'm a punk camper," admitted Roscoe.

"You can see for yourself," said Tom, with blunt frankness, "that you'd have been up against it here pretty soon. You'd have had to go to Leeds for stuff, and they'd ask you for your registration card, maybe."

"I don't see how I'm going to leave you here," Roscoe said doubtfully.

"I'll be all right," said Tom.

"What will you say to them when you come home?"

"I'll tell 'em I ain't going to answer any questions. I'll say I had to go away for something very important."

"You'll be in bad," Roscoe said thoughtfully.

"I won't be misjudged," said Tom simply; "I got the reputation of being kind o' queer, anyway, and they'll just say I had a freak. You can see for yourself," he added, "that it wouldn't be good for us to go back together—even if my foot was all right."74

"It's better, isn't it?" Roscoe asked anxiously.

"Sure it is. It's only strained—that's different from being sprained—and my head's all right now."

"What will you do?" Roscoe asked, looking troubled and unconvinced in spite of Tom's assurances.

"I was going to come up here and camp alone over the Fourth of July, anyway," said Tom. "I always meant to do that. I'll call this a vacation—as you might say. I got to thank you for that."

"You've got to thank me for a whole lot," said Roscoe ironically; "for a broken head and a lame ankle and missing all the fun last night, and losing your job, maybe."

"I ain't worryin'," said Tom. "I hit the right trail."

"And saved me from being—no, I'm one, anyway, now——"

"No, you ain't; you just got rattled. Now you can see straight, so you have to go back right away. As soon as my foot's better, I'll go down to Temple Camp. That'll be to-morrow—or sure day after to-morrow. I'm going to look around the camp and see if everything is all right, and then I'll hike into Leeds and go down by the train.75 If I was to go limping back, they might think things; and, anyway, it's better for you to get there alone."

"Are you sure your foot'll be all right?" Roscoe asked.

"Sure. I'll read that book of yours, and maybe I'll catch some trout for lunch ..."

Roscoe sprang forward impulsively and grasped Tom's hand.

"Now you spilled my coffee," said Tom impassively.

"Tom, I don't know how to take you," Roscoe said feelingly; "you're a puzzle to me. I never realized what sort of a chap you were—when I used to make fun of you and jolly you. Let's feel your old muscle," he added, on the impulse. "I wish I had a muscle like that...."