« back

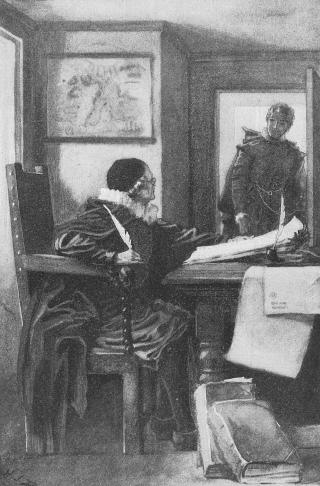

Saint Bartholomew's Eve:

A Tale of the Huguenot Wars

By G. A. Henty.

Illustrated by H. J. Draper.

| Preface. | |

| Chapter 1: | Driven From Home. |

| Chapter 2: | An Important Decision. |

| Chapter 3: | In A French Chateau. |

| Chapter 4: | An Experiment. |

| Chapter 5: | Taking The Field. |

| Chapter 6: | The Battle Of Saint Denis. |

| Chapter 7: | A Rescue. |

| Chapter 8: | The Third Huguenot War. |

| Chapter 9: | An Important Mission. |

| Chapter 10: | The Queen Of Navarre. |

| Chapter 11: | Jeanne Of Navarre. |

| Chapter 12: | An Escape From Prison. |

| Chapter 13: | At Laville. |

| Chapter 14: | The Assault On The Chateau. |

| Chapter 15: | The Battle Of Jarnac. |

| Chapter 16: | A Huguenot Prayer Meeting. |

| Chapter 17: | The Battle Of Moncontor. |

| Chapter 18: | A Visit Home. |

| Chapter 19: | In A Net. |

| Chapter 20: | The Tocsin. |

| Chapter 21: | Escape. |

| Chapter 22: | Reunited. |

Preface.

It is difficult, in these days of religious toleration, to understand why men should, three centuries ago, have flown at each others' throats in the name of the Almighty; still less how, in cold blood, they could have perpetrated hideous massacres of men, women, and children. The Huguenot wars were, however, as much political as religious. Philip of Spain, at that time the most powerful potentate of Europe, desired to add France to the countries where his influence was all powerful; and in the ambitious house of Guise he found ready instruments.

For a time the new faith, that had spread with such rapidity in Germany, England, and Holland, made great progress in France, also. But here the reigning family remained Catholic, and the vigorous measures they adopted, to check the growing tide, drove those of the new religion to take up arms in self defence. Although, under the circumstances, the Protestants can hardly be blamed for so doing, there can be little doubt that the first Huguenot war, though the revolt was successful, was the means of France remaining a Catholic country. It gave colour to the assertions of the Guises and their friends that the movement was a political one, and that the Protestants intended to grasp all power, and to overthrow the throne of France. It also afforded an excuse for the cruel persecutions which followed, and rallied to the Catholic cause numbers of those who were, at heart, indifferent to the question of religion, but were Royalists rather than Catholics.

The great organization of the Church of Rome laboured among all classes for the destruction of the growing heresy. Every pulpit in France resounded with denunciations of the Huguenots, and passionate appeals were made to the bigotry and fanaticism of the more ignorant classes; so that, while the power of the Huguenots lay in some of the country districts, the mobs of the great towns were everywhere the instruments of the priests.

I have not considered it necessary to devote any large portion of my story to details of the terrible massacres of the period, nor to the atrocious persecutions to which the Huguenots were subjected; but have, as usual, gone to the military events of the struggle for its chief interest. For the particulars of these, I have relied chiefly upon the collection of works of contemporary authors published by Monsieur Zeller, of Paris; the Memoirs of Francois de la Noue, and other French authorities.

G. A. Henty.

Chapter 1: Driven From Home.

In the year 1567 there were few towns in the southern counties of England that did not contain a colony, more or less large, of French Protestants. For thirty years the Huguenots had been exposed to constant and cruel persecutions; many thousands had been massacred by the soldiery, burned at the stake, or put to death with dreadful tortures. Fifty thousand, it was calculated, had, in spite of the most stringent measures of prevention, left their homes and made their escape across the frontiers. These had settled for the most part in the Protestant cantons of Switzerland, in Holland, or England. As many of those who reached our shores were but poorly provided with money, they naturally settled in or near the ports of landing.

Canterbury was a place in which many of the unfortunate emigrants found a home. Here one Gaspard Vaillant, his wife, and her sister, who had landed in the year 1547, had established themselves. They were among the first comers, but the French colony had grown, gradually, until it numbered several hundreds. The Huguenots were well liked in the town, being pitied for their misfortunes, and admired for the courage with which they bore their losses; setting to work, each man at his trade if he had one, or if not, taking to the first work that came to hand. They were quiet and God-fearing folk; very good towards each other, and to their poor countrymen on their way from the coast to London, entertaining them to the best of their power, and sending them forward on their way with letters to the Huguenot committee in London, and with sufficient money in their pockets to pay their expenses on the journey, and to maintain them for a while until some employment could be found for them.

Gaspard Vaillant had been a landowner near Civray, in Poitou. He was connected by blood with several noble families in that district, and had been among the first to embrace the reformed religion. For some years he had not been interfered with, as it was upon the poorer and more defenceless classes that the first fury of the persecutors fell; but as the attempts of Francis to stamp out the new sect failed, and his anger rose more and more against them, persons of all ranks fell under the ban. The prisons were filled with Protestants who refused to confess their errors; soldiers were quartered in the towns and villages, where they committed terrible atrocities upon the Protestants; and Gaspard, seeing no hope of better times coming, or of being permitted to worship in peace and quietness, gathered together what money he could and made his way, with his wife and her sister, to La Rochelle, whence he took ship to London.

Disliking the bustle of a large town, he was recommended by some of his compatriots to go down to Canterbury, where three or four fugitives from his own part of the country had settled. One of these was a weaver by trade, but without money to manufacture looms or set up in his calling. Gaspard joined him as partner, embarking the little capital he had saved; and being a shrewd, clear-headed man he carried on the business part of the concern, while his partner Lequoc worked at the manufacture.

As the French colony in Canterbury increased, they had no difficulty in obtaining skilled hands from among them. The business grew in magnitude, and the profits were large, in spite of the fact that numbers of similar enterprises had been established by the Huguenot immigrants in London, and other places. They were, indeed, amply sufficient to enable Gaspard Vaillant to live in the condition of a substantial citizen, to aid his fellow countrymen, and to lay by a good deal of money.

His wife's sister had not remained very long with him. She had, upon their first arrival, given lessons in her own language to the daughters of burgesses, and of the gentry near the town; but, three years after the arrival of the family there, she had married a well-to-do young yeoman who farmed a hundred acres of his own land, two miles from the town. His relations and neighbours had shaken their heads over what they considered his folly, in marrying the pretty young Frenchwoman; but ere long they were obliged to own that his choice had been a good one.

Just after his first child was born he was, when returning home one evening from market, knocked down and run over by a drunken carter, and was so injured that for many months his life was in danger. Then he began to mend, but though he gained in strength he did not recover the use of his legs, being completely paralysed from the hips downward; and, as it soon appeared, was destined to remain a helpless invalid all his life. From the day of the accident Lucie had taken the management of affairs in her hands, and having been brought up in the country, and being possessed of a large share of the shrewdness and common sense for which Frenchwomen are often conspicuous, she succeeded admirably. The neatness and order of the house, since their marriage, had been a matter of surprise to her husband's friends; and it was not long before the farm showed the effects of her management. Gaspard Vaillant assisted her with his counsel and, as the French methods of agriculture were considerably in advance of those in England, instead of things going to rack and ruin, as John Fletcher's friends predicted, its returns were considerably augmented.

Naturally, she at first experienced considerable opposition. The labourers grumbled at what they called new-fangled French fashions; but when they left her, their places were supplied by her countrymen, who were frugal and industrious, accustomed to make the most out of small areas of ground, and to turn every foot to the best advantage. Gradually the raising of corn was abandoned, and a large portion of the farm devoted to the growing of vegetables; which, by dint of plentiful manuring and careful cultivation, were produced of a size and quality that were the surprise and admiration of the neighbourhood, and gave her almost a monopoly of the supply of Canterbury.

The carters were still English; partly because Lucie had the good sense to see that, if she employed French labourers only, she would excite feelings of jealousy and dislike among her neighbours; and partly because she saw that, in the management of horses and cattle, the Englishmen were equal, if not superior, to her countrymen.

Her life was a busy one. The management of the house and farm would, alone, have been a heavy burden to most people; but she found ample time for the tenderest care of the invalid, whom she nursed with untiring affection.

"It is hard upon a man of my size and inches, Lucie," he said one day, "to be lying here as helpless as a sick child; and yet I don't feel that I have any cause for discontent. I should like to be going about the farm, and yet I feel that I am happier here, lying watching you singing so contentedly over your work, and making everything so bright and comfortable. Who would have thought, when I married a little French lady, that she was going to turn out a notable farmer? All my friends tell me that there is not a farm like mine in all the country round, and that the crops are the wonder of the neighbourhood; and when I see the vegetables that are brought in here, I should like to go over the farm, if only for once, just to see them growing."

"I hope you will be able to do that, some day, dear. Not on foot, I am afraid; but when you get stronger and better, as I hope you will, we will take you round in a litter, and the bright sky and the fresh air will do you good."

Lucie spoke very fair English now, and her husband had come to speak a good deal of French; for the service of the house was all in that language, the three maids being daughters of French workmen in the town. The waste and disorder of those who were in the house when her husband first brought her there had appalled her; and the women so resented any attempt at teaching, on the part of the French madam, that after she had tried several sets with equally bad results, John Fletcher had consented to the introduction of French girls; bargaining only that he was to have good English fare, and not French kickshaws. The Huguenot customs had been kept up, and night and morning the house servants, with the French neighbours and their families, all assembled for prayer in the farmhouse.

To this John Fletcher had agreed without demur. His father had been a Protestant, when there was some danger in being so; and he himself had been brought up soberly and strictly. Up to the time of his accident there had been two congregations, he himself reading the prayers to his farm hands, while Lucie afterwards read them in her own language to her maids; but as the French labourers took the place of the English hands, only one service was needed.

When John Fletcher first regained sufficient strength to take much interest in what was passing round, he was alarmed at the increase in the numbers of those who attended these gatherings. Hitherto four men had done the whole work of the farm; now there were twelve.

"Lucie, dear," he said uneasily one day, "I know that you are a capital manager; but it is impossible that a farm the size of ours can pay, with so many hands on it. I have never been able to do more than pay my way, and lay by a few pounds every year, with only four hands, and many would have thought three sufficient; but with twelve--and I counted them this morning--we must be on the highroad to ruin."

"I will not ruin you, John. Do you know how much money there was in your bag when you were hurt, just a year ago now?"

"Yes, I know there were thirty-three pounds."

His wife went out of the room and returned with a leather bag.

"Count them, John," she said.

There were forty-eight. Fifteen pounds represented a vastly greater sum, at that time, than they do at present; and John Fletcher looked up from the counting with amazement.

"This can't be all ours, Lucie. Your brother must have been helping us."

"Not with a penny, doubting man," she laughed. "The money is yours, all earned by the farm; perhaps not quite all, because we have not more than half as many animals as we had before. But, as I told you, we are growing vegetables, and for that we must have more men than for corn. But, as you see, it pays. Do not fear about it, John. If God should please to restore you to health and strength, most gladly will I lay down the reins; but till then I will manage as best I may and, with the help and advice of my brother and his friends, shall hope, by the blessing of God, to keep all straight."

The farm throve, but its master made but little progress towards recovery. He was able, however, occasionally to be carried round in a hand litter, made for him upon a plan devised by Gaspard Vaillant; in which he was supported in a half-sitting position, while four men bore him as if in a Sedan chair.

But it was only occasionally that he could bear the fatigue of such excursions. Ordinarily he lay on a couch in the farmhouse kitchen, where he could see all that was going on there; while in warm summer weather he was wheeled outside, and lay in the shade of the great elm, in front of the house.

The boy, Philip--for so he had been christened, after John Fletcher's father--grew apace and, as soon as he was old enough to receive instruction, his father taught him his letters out of a horn book, until he was big enough to go down every day to school in Canterbury. John himself was built upon a large scale, and at quarterstaff and wrestling could, before he married, hold his own with any of the lads of Kent; and Philip bade fair to take after him, in skill and courage. His mother would shake her head reprovingly when he returned, with his face bruised and his clothes torn, after encounters with his schoolfellows; but his father took his part.

"Nay, nay, wife," he said one day, "the boy is eleven years old now, and must not grow up a milksop. Teach him if you will to be honest and true, to love God, and to hold to the faith; but in these days it needs that men should be able to use their weapons, also. There are your countrymen in France, who ere long will be driven to take up arms, for the defence of their faith and lives from their cruel persecutors; and, as you have told me, many of the younger men, from here and elsewhere, will assuredly go back to aid their brethren.

"We may even have trials here. Our Queen is a Protestant, and happily at present we can worship God as we please, in peace; but it was not so in the time of Mary, and it may be that troubles may again fall upon the land, seeing that as yet the Queen is not married. Moreover, Philip of Spain has pretensions to rule here; and every Englishman may be called upon to take up bow, or bill, for his faith and country. Our co-religionists in Holland and France are both being cruelly persecuted, and it may well be that the time will come when we shall send over armies to their assistance.

"I would that the boy should grow up both a good Christian and a stout soldier. He comes on both sides of a fighting stock. One of my ancestors fought at Agincourt, and another with the Black Prince at Cressy and Poitiers; while on your side his blood is noble and, as we know, the nobles of France are second to none in bravery.

"Before I met you I had thoughts of going out, myself, to fight among the English bands who have engaged on the side of the Hollanders. I had even spoken to my cousin James about taking charge of the farm, while I was away. I would not have sold it, for Fletchers held this land before the Normans set foot in England; but I had thoughts of borrowing money upon it, to take me out to the war, when your sweet face drove all such matters from my mind.

"Therefore, Lucie, while I would that you should teach the boy to be good and gentle in his manners, so that if he ever goes among your French kinsmen he shall be able to bear himself as befits his birth, on that side; I, for my part--though, alas, I can do nothing myself--will see that he is taught to use his arms, and to bear himself as stoutly as an English yeoman should, when there is need of it.

"So, wife, I would not have him chidden when he comes home with a bruised face, and his garments somewhat awry. A boy who can hold his own, among boys, will some day hold his own among men; and the fisticuffs, in which our English boys try their strength, are as good preparation as are the courtly sports; in which, as you tell me, young French nobles are trained. But I would not have him backward in these, either. We English, thank God, have not had much occasion to draw a sword since we broke the strength of Scotland on Flodden Field; and in spite of ordinances, we know less than we should do of the use of our weapons. Even the rules that every lad shall practise shooting at the butts are less strictly observed than they should be. But in this respect our deficiencies can be repaired, in his case; for here in Canterbury there are several of your countrymen of noble birth, and doubtless among these we shall be able to find an instructor for Phil. Many of them are driven to hard shifts to procure a living; and since that bag of yours is every day getting heavier, and we have but him to spend it upon, we will not grudge giving him the best instruction that can be procured."

Lucie did not dispute her husband's will; but she nevertheless tried to enlist Gaspard Vaillant--who was frequently up at the farm with his wife in the evening, for he had a sincere liking for John Fletcher--on her side; and to get him to dissuade her husband from putting thoughts into the boy's head that might lead him, some day, to be discontented with the quiet life on the farm. She found, however, that Gaspard highly approved of her husband's determination.

"Fie upon you, Lucie. You forget that you and Marie are both of noble blood, in that respect being of condition somewhat above myself, although I too am connected with many good families in Poitou. In other times I should have said it were better that the boy should grow up to till the land, which is assuredly an honourable profession, rather than to become a military adventurer, fighting only for vainglory. But in our days the sword is not drawn for glory, but for the right to worship God in peace.

"No one can doubt that, ere long, the men of the reformed religion will take up arms to defend their right to live, and worship God, in their own way. The cruel persecutions under Francis the First, Henry the Second, and Francis the Second have utterly failed in their object. When Merindol, Cabrieres, and twenty-two other towns and villages were destroyed, in 1547; and persons persecuted and forced to recant, or to fly as we did; it was thought that we were but a handful, whom it would be easy to exterminate. But in spite of edict after edict, of persecution, slaughterings, and burnings, in spite of the massacres of Amboise and others, the reformed religion has spread so greatly that even the Guises are forced to recognize it as a power. At Fontainebleau Admiral Coligny, Montmorency, the Chatillons, and others openly professed the reformed religion, and argued boldly for tolerance; while Conde and Navarre, although they declined to be present, were openly ranged on their side. Had it not been that Henry the Second and Francis were both carried off by the manifest hand of God, the first by a spear thrust at a tournament, the second by an abscess in the ear, France would have been the scene of deadly strife; for both were, when so suddenly smitten, on the point of commencing a war of extermination.

"But it is only now that the full strength of those who hold the faith is manifested. Beza, the greatest of the reformers next to Calvin himself, and twelve of our most learned and eloquent pastors are at Poissy, disputing upon the faith with the Cardinal of Lorraine and the prelates of the Romish church, in the presence of the young king, the princes, and the court. It is evident that the prelates are unable to answer the arguments of our champions. The Guises, I hear, are furious; for the present Catharine, the queen mother, is anxious for peace and toleration, and it is probable that the end of this argument at Poissy will be an edict allowing freedom of worship.

"But this will only infuriate still more the Papists, urged on by Rome and Philip of Spain. Then there will be an appeal to arms, and the contest will be a dreadful one. Navarre, from all I hear, has been well-nigh won over by the Guises; but his noble wife will, all say, hold the faith to the end, and her kingdom will follow her. Conde is as good a general as Guise, and with him there is a host of nobles: Rochefoucauld, the Chatillons, Soubise, Gramont, Rohan, Genlis, and a score of others. It will be terrible, for in many cases father and son will be ranged on opposite sides, and brother will fight against brother."

"But surely, Gaspard, the war will not last for years?"

"It may last for generations," the weaver said gloomily, "though not without intermissions; for I believe that, after each success on one side or the other, there will be truces and concessions; to be followed by fresh persecutions and fresh wars, until either the reformed faith becomes the religion of all France, or is entirely stamped out.

"What is true of France is true of Holland. Philip will annihilate the reformers there, or they will shake off the yoke of Spain. England will be driven to join in one or both struggles; for if papacy is triumphant in France and Holland, Spain and France would unite against her.

"So you see, sister, that in my opinion we are at the commencement of a long and bloody struggle for freedom of worship; and at any rate it will be good that the boy should be trained as he would have been, had you married one of your own rank in France; in order that, when he comes to man's estate, he may be able to wield a sword worthily in the defence of the faith.

"Had I sons, I should train them as your husband intends to train Phil. It may be that he will never be called upon to draw a sword, but the time he has spent in acquiring its use will not be wasted. These exercises give firmness and suppleness to the figure, quickness to the eye, and briskness of decision to the mind. A man who knows that he can, at need, defend his life if attacked, whether against soldiers in the field or robbers in the street, has a sense of power and self reliance that a man, untrained in the use of the strength God has given him, can never feel. I was instructed in arms when a boy, and I am none the worse weaver for it.

"Do not forget, Lucie, that the boy has the blood of many good French families in his veins; and you should rejoice that your husband is willing that he shall be so trained that, if the need should ever come, he shall do no discredit to his ancestors on our side. These English have many virtues, which I freely recognize; but we cannot deny that many of them are somewhat rough and uncouth, being wondrous lacking in manners and coarse in speech. I am sure that you yourself would not wish your son to grow up like many of the young fellows who come into town on market day. Your son will make no worse a farmer for being trained as a gentleman. You yourself have the training of a French lady, and yet you manage the farm to admiration.

"No, no, Lucie, I trust that between us we shall make a true Christian and a true gentleman of him; and that, if needs be, he will show himself a good soldier, also."

And so, between his French relatives and his sturdy English father, Philip Fletcher had an unusual training. Among the Huguenots he learned to be gentle and courteous; to bear himself among his elders respectfully, but without fear or shyness; to consider that, while all things were of minor consequence in comparison to the right to worship God in freedom and purity, yet that a man should be fearless of death, ready to defend his rights, but with moderation and without pushing them to the injury of others; that he should be grave and decorous of speech, and yet of a happy and cheerful spirit. He strove hard so to deport himself that if, at any time, he should return to his mother's country, he could take his place among her relations without discredit. He learned to fence, and to dance.

Some of the stricter of the Huguenots were of opinion that the latter accomplishment was unnecessary, if not absolutely sinful; but Gaspard Vaillant was firm on this point.

"Dancing is a stately and graceful exercise," he said, "and like the use of arms, it greatly improves the carriage and poise of the figure. Queen Elizabeth loves dancing, and none can say that she is not a good Protestant. Every youth should be taught to dance, if only he may know how to walk. I am not one of those who think that, because a man is a good Christian, he should necessarily be awkward and ungainly in speech and manner, adverse to innocent gaieties, narrow in his ideas, ill dressed and ill mannered, as I see are many of those most extreme in religious matters, in this country."

Upon the other hand, in the school playground, under the shadow of the grand cathedral, Phil was as English as any; being foremost in their rough sports, and ready for any fun or mischief.

He fought many battles, principally because the difference of his manner from that of the others often caused him to be called "Frenchy." The epithet in itself was not displeasing to him; for he was passionately attached to his mother, and had learned from her to love her native country; but applied in derision it was regarded by him as an insult, and many a tough battle did he fight, until his prowess was so generally acknowledged that the name, though still used, was no longer one of disrespect.

In figure, he took after his French rather than his English ancestors. Of more than average height for his age, he was apparently slighter in build than his schoolfellows. It was not that he lacked width of chest, but that his bones were smaller and his frame less heavy. The English boys, among themselves, sometimes spoke of him as "skinny," a word considered specially appropriate to Frenchmen; but though he lacked their roundness and fulness of limb, and had not an ounce of superfluous flesh about him, he was all sinew and wire; and while in sheer strength he was fully their equal, he was incomparably quicker and more active.

Although in figure and carriage he took after his mother's countrymen, his features and expression were wholly English. His hair was light brown, his eyes a bluish gray, his complexion fair, and his mouth and eyes alive with fun and merriment. This, however, seldom found vent in laughter. His intercourse with the grave Huguenots, saddened by their exile, and quiet and restrained in manner, taught him to repress mirth, which would have appeared to them unseemly; and to remain a grave and silent listener to their talk of their unhappy country, and their discussions on religious matters.

To his schoolfellows he was somewhat of an enigma. There was no more good-tempered young fellow in the school, no one more ready to do a kindness; but they did not understand why, when he was pleased, he smiled while others roared with laughter; why when, in their sports, he exerted himself to the utmost, he did so silently while others shouted; why his words were always few and, when he differed from others, he expressed himself with a courtesy that puzzled them; why he never wrangled nor quarrelled; and why any trick played upon an old woman, or a defenceless person, roused him to fury.

As a rule, when boys do not quite understand one of their number they dislike him. Philip Fletcher was an exception. They did not understand him, but they consoled themselves under this by the explanation that he was half a Frenchman, and could not be expected to be like a regular English boy; and they recognized instinctively that he was their superior.

Much of Philip's time was spent at the house of his uncle, and among the Huguenot colony. Here also were many boys of his own age. These went to a school of their own, taught by the pastor of their own church, who held weekly services in the crypt of the cathedral, which had been granted to them for that purpose by the dean. While, with his English schoolfellows, he joined in sports and games; among these French lads the talk was sober and quiet. Scarce a week passed but some fugitive, going through Canterbury, brought the latest news of the situation in France, and the sufferings of their co-religionist friends and relations there; and the political events were the chief topics of conversation.

The concessions made at the Conference of Poissy had infuriated the Catholics, and the war was brought on by the Duke of Guise who, passing with a large band of retainers through the town of Vassy in Champagne, found the Huguenots there worshipping in a barn. His retainers attacked them, slaying men, women, and children--some sixty being killed, and a hundred or more left terribly wounded.

The Protestant nobles demanded that Francis of Guise should be punished for this atrocious massacre, but in vain; and Guise, on entering Paris, in defiance of Catharine's prohibition, was received with royal honours by the populace. The Cardinal of Lorraine, the duke's brother, the duke himself, and their allies, the Constable Montmorency and Marshal Saint Andre, assumed so threatening an attitude that Catharine left Paris and went to Melun, her sympathies at this period being with the reformers; by whose aid, alone, she thought that she could maintain her influence in the state against that of the Guises.

Conde was forced to leave Paris with the Protestant nobles, and from all parts of France the Huguenots marched to assist him. Coligny, the greatest of the Huguenot leaders, hesitated; being, above all things, reluctant to plunge France into civil war. But the entreaties of his noble wife, of his brothers and friends, overpowered his reluctance. Conde left Meaux, with fifteen hundred horse, with the intention of seizing the person of the young king; but he had been forestalled by the Guises, and moved to Orleans, where he took up his headquarters. All over France the Huguenots rose in such numbers as astonished their enemies, and soon became possessed of a great many important cities.

Their leaders had endeavoured, in every way, to impress upon them the necessity of behaving as men who fought only for the right to worship God; and for the most part these injunctions were strictly obeyed. In one matter, alone, the Huguenots could not be restrained. For thirty years the people of their faith had been executed, tortured, and slain; and their hatred of the Romish church manifested itself by the destruction of images and pictures of all kinds, in the churches of the towns of which they obtained possession. Only in the southeast of France was there any exception to the general excellence of their conduct. Their persecution here had always been very severe, and in the town of Orange the papal troops committed a massacre almost without a parallel in its atrocity. The Baron of Adrets, on behalf of the Protestants, took revenge by massacres equally atrocious; but while the butchery at Orange was hailed with approbation and delight by the Catholic leaders, those promoted by Adrets excited such a storm of indignation, among the Huguenots of all classes, that he shortly afterwards went over to the other side, and was found fighting against the party he had disgraced.

At Toulouse three thousand Huguenots were massacred, and in other towns where the Catholics were in a majority terrible persecutions were carried out.

It was nearly a year after the massacre at Vassy before the two armies met in battle. The Huguenots had suffered greatly, by the delays caused by attempts at negotiations and compromise. Conde's army was formed entirely of volunteers, and the nobles and gentry, as their means became exhausted, were compelled to return home with their retainers; while many were forced to march to their native provinces, to assist their co-religionists there to defend themselves from their Catholic neighbours.

England had entered, to a certain extent, upon the war; Elizabeth, after long vacillation, having at length agreed to send six thousand men to hold the towns of Havre, Dieppe, and Rouen, providing these three towns were handed over to her; thus evincing the same calculating greed that marked her subsequent dealings with the Dutch, in their struggle for freedom.

In vain Conde and Coligny begged her not to impose conditions that Frenchmen would hold to be infamous to them. In vain Throgmorton, her ambassador at Paris, warned her that she would alienate the Protestants of France from her; while the possession of the cities would avail her but little. In vain her minister, Cecil, urged her frankly to ally herself with the Protestants. From the first outbreak of the war for freedom of conscience in France, to the termination of the struggle in Holland, Elizabeth baffled both friends and enemies by her vacillation and duplicity, and her utter want of faith; doling out aid in the spirit of a huckster rather than a queen, so that she was, in the end, even more hated by the Protestants of Holland and France than by the Catholics of France and Spain.

To those who look only at the progress made by England, during the reign of Elizabeth--thanks to her great ministers, her valiant sailors and soldiers, long years of peace at home, and the spirit and energy of her people--Elizabeth may appear a great monarch. To those who study her character from her relations with the struggling Protestants of Holland and France, it will appear that she was, although intellectually great, morally one of the meanest, falsest, and most despicable of women.

Rouen, although stoutly defended by the inhabitants, supported by Montgomery with eight hundred soldiers, and five hundred Englishmen under Killegrew of Pendennis, was at last forced to surrender. The terms granted to the garrison were basely violated, and many of the Protestants put to death. The King of Navarre, who had, since he joined the Catholic party, shown the greatest zeal in their cause, commanded the besiegers. He was wounded in one of the attacks upon the town, and died shortly afterwards.

The two armies finally met, on the 19th of December, 1562. The Catholic party had sixteen thousand foot, two thousand horse, and twenty-two cannon; the Huguenots four thousand horse, but only eight thousand infantry and five cannon. Conde at first broke the Swiss pikemen of the Guises, while Coligny scattered the cavalry of Constable Montmorency, who was wounded and taken prisoner; but the infantry of the Catholics defeated those of the Huguenots, the troops sent by the German princes to aid the latter behaving with great cowardice. Conde's horse was killed under him, and he was made prisoner. Coligny drew off the Huguenot cavalry and the remains of the infantry in good order, and made his retreat unmolested.

The Huguenots had been worsted in the battle, and the loss of Conde was a serious blow; but on the other hand Marshal Saint Andre was killed, and the Constable Montmorency a prisoner. Coligny was speedily reinforced; and the assassination of the Duke of Guise, by an enthusiast of the name of Jean Poltrot, more than equalized matters.

Both parties being anxious to treat, terms of peace were arranged; on the condition that the Protestant lords should be reinstated in their honours and possessions; all nobles and gentlemen should be allowed to celebrate, in their own houses, the worship of the reformed religion; that in every bailiwick the Protestants should be allowed to hold their religious services, in the suburbs of one city, and should also be permitted to celebrate it, in one or two places, inside the walls of all the cities they held at the time of the signature of the truce. This agreement was known as the Treaty of Amboise, and sufficed to secure peace for France, until the latter end of 1567.

Chapter 2: An Important Decision.

One day in June, 1567, Gaspard Vaillant and his wife went up to Fletcher's farm.

"I have come up to have a serious talk with you, John, about Philip. You see, in a few months he will be sixteen. He is already taller than I am. Rene and Gustave both tell me that they have taught him all they know with sword and dagger; and both have been stout men-at-arms in their time, and assure me that the lad could hold his own against any young French noble of his own age, and against not a few men. It is time that we came to some conclusion about his future."

"I have thought of it much, Gaspard. Lying here so helpless, my thoughts do naturally turn to him. The boy has grown almost beyond my power of understanding. Sometimes, when I hear him laughing and jesting with the men, or with some of his school friends whom he brings up here, it seems to me that I see myself again in him; and that he is a merry young fellow, full of life and fun, and able to hold his own at singlestick, or to foot it round the maypole with any lad in Kent of his age. Then again, when he is talking with his mother, or giving directions in her name to the French labourers, I see a different lad, altogether: grave and quiet, with a gentle, courteous way, fit for a young noble ten years his senior. I don't know but that between us, Gaspard, we have made a mess of it; and that it might have been better for him to have grown up altogether as I was, with no thought or care save the management of his farm, with a liking for sport and fun, when such came in his way."

"Not at all, not at all," Gaspard Vaillant broke in hastily, "we have made a fine man of him, John; and it seems to me that he possesses the best qualities of both our races. He is frank and hearty, full of life and spirits when, as you say, occasion offers; giving his whole heart either to work or play, with plenty of determination, and what you English call backbone. There is, in fact, a solid English foundation to his character. Then from our side he has gained the gravity of demeanour that belongs to us Huguenots; with the courtesy of manner, the carriage and bearing of a young Frenchman of good blood. Above all, John, he is a sober Christian, strong in the reformed faith, and with a burning hatred against its persecutors, be they French or Spanish.

"Well then, being what he is, what is to be done with him? In the first place, are you bent upon his remaining here? I think that, with his qualities and disposition, it would be well that for a while he had a wider scope. Lucie has managed the farm for the last fifteen years, and can well continue to do so for another ten, if God should spare her; and my own opinion is that, for that time, he might be left to try his strength, and to devote to the good cause the talents God has given him, and the skill and training that he has acquired through us; and that it would be for his good to make the acquaintance of his French kinsfolk, and to see something of the world."

"I know that is Lucie's wish, also, Gaspard; and I have frequently turned the matter over in my mind, and have concluded that, should it be your wish also, it would be well for me to throw no objections in the way. I shall miss the boy sorely; but young birds cannot be kept always in the nest, and I think that the lad has such good stuff in him that it were a pity to keep him shut up here."

"Now, John," his brother-in-law went on, "although I may never have said quite as much before, I have said enough for you to know what my intentions are. God has not been pleased to bestow children upon us; and Philip is our nearest relation, and stands to us almost in the light of a son. God has blest my work for the last twenty years, and though I have done, I hope, fully my share towards assisting my countrymen in distress, putting by always one-third of my income for that purpose, I am a rich man. The factory has grown larger and larger; not because we desired greater gains, but that I might give employment to more and more of my countrymen. Since the death of Lequoc, twelve years ago, it has been entirely in my hands and, living quietly as we have done, a greater portion of the profits have been laid by every year; therefore, putting out of account the money that my good sister has laid by, Philip will start in life not ill equipped.

"I know that the lad has said nothing of any wishes he may entertain--at his age it would not be becoming for him to do so, until his elders speak--but of late, when we have read to him letters from our friends in France, or when he has listened to the tales of those freshly arrived from their ruined homes, I have noted that his colour rose; that his fingers tightened, as if on a sword; and could see how passionately he was longing to join those who were struggling against their cruel oppressors. Not less interested has he been in the noble struggle that the Dutch are making against the Spaniards; a struggle in which many of our exiled countrymen are sharing.

"One of his mother's cousins, the Count de La Noue, is, as you know, prominent among the Huguenot leaders; and others of our relatives are ranged on the same side. At present there is a truce, but both parties feel that it is a hollow one; nevertheless it offers a good opportunity for him to visit his mother's family. Whether there is any prospect of our ever recovering the lands which were confiscated on our flight is uncertain. Should the Huguenots ever maintain their ground, and win freedom of worship in France, it may be that the confiscated estates will in many cases be restored; as to that, however, I am perfectly indifferent. Were I a younger man, I should close my factory, return to France, and bear my share in the defence of the faith. As it is, I should like to send Philip over as my substitute.

"It would, at any rate, be well that he should make the acquaintance of his kinsfolk in France; although even I should not wish that he should cease to regard England as his native country and home. Hundreds of young men, many no older than himself, are in Holland fighting against the persecutors; and risking their lives, though having no kinship with the Dutch, impelled simply by their love of the faith and their hatred of persecution.

"I have lately, John, though the matter has been kept quiet, purchased the farms of Blunt and Mardyke, your neighbours on either hand. Both are nearly twice the size of your own. I have arranged with the men that, for the present, they shall continue to work them as my tenants, as they were before the tenants of Sir James Holford; who, having wasted his money at court, has been forced to sell a portion of his estates. Thus, some day Phil will come into possession of land which will place him in a good position, and I am prepared to add to it considerably. Sir James Holford still gambles away his possessions; and I have explained, to his notary, my willingness to extend my purchases at any time, should he desire to sell. I should at once commence the building of a comfortable mansion, but it is scarce worth while to do so; for it is probable that, before many years, Sir James may be driven to part with his Hall, as well as his land. In the meantime I am ready to provide Philip with an income which will enable him to take his place with credit among our kinsfolk, and to raise a company of some fifty men to follow him in the field, should Conde and the Huguenots again be driven to struggle against the Guises.

"What do you think?"

"I think, in the first place, that Lucie and I should be indeed grateful to you, Gaspard, for your generous offer. As to his going to France, that I must talk over with his mother; whose wishes in this, as in all respects, are paramount with me. But I may say at once that, lying here as I do, thinking of the horrible cruelties and oppressions to which men and women are subjected for the faith's sake in France and Holland, I feel that we, who are happily able to worship in peace and quiet, ought to hesitate at no sacrifice on their behalf; and moreover, seeing that, owing to my affliction, he owes what he is rather to his mother and you than to me, I think your wish that he should make the acquaintance of his kinsfolk in France is a natural one. I have no wish for the lad to become a courtier, English or French; nor that he should, as Englishmen have done before now in foreign armies, gain great honour and reputation; but if it is his wish to fight on behalf of the persecuted people of God, whether in France or in Holland, he will do so with my heartiest goodwill; and if he die, he could not die in a more glorious cause.

"Let us talk of other matters now, Gaspard. This is one that needs thought before more words are spoken."

Two days later, John Fletcher had a long talk with Phil. The latter was delighted when he heard the project, which was greatly in accord with both sides of his character. As an English lad, he looked forward eagerly to adventure and peril; as French and of the reformed religion, he was rejoiced at the thought of fighting with the Huguenots against their persecutors, and of serving under the men with whose names and reputations he was so familiar.

"I do not know your uncle's plans for you, as yet, Phil," his father said. "He went not into such matters, leaving these to be talked over after it had been settled whether his offer should be accepted or not. He purposes well by you, and regards you as his heir. He has already bought Blunt and Mardyke's farms, and purposes to buy other parts of the estates of Sir James Holford, as they may slip through the knight's fingers at the gambling table. Therefore, in time, you will become a person of standing in the county; and although I care little for these things now, Phil, yet I should like you to be somewhat more than a mere squire; and if you serve for a while under such great captains as Coligny and Conde, it will give you reputation and weight.

"Your good uncle and his friends think little of such matters, but I own that I am not uninfluenced by them. Coligny, for example, is a man whom all honour; and that honour is not altogether because he is leader of the reformed faith, but because he is a great soldier. I do not think that honour and reputation are to be despised. Doubtless the first thing of all is that a man should be a good Christian. But that will in no way prevent him from being a great man; nay, it will add to his greatness.

"You have noble kinsfolk in France, to some of whom your uncle will doubtless commit you; and it may be that you will have opportunities of distinguishing yourself. Should such occur, I am sure you will avail yourself of them, as one should do who comes of good stock on both sides; for although we Fletchers have been but yeomen, from generation to generation, we have been ever ready to take and give our share of hard blows when they were going; and there have been few battles fought, since William the Norman came over, that a Fletcher has not fought in the English ranks; whether in France, in Scotland, or in our own troubles.

"Therefore it seems to me but natural that, for many reasons, you should desire at your age to take part in the fighting; as an Englishman, because Englishmen fought six years ago under the banner of Conde; as a Protestant, on behalf of our persecuted brethren; as a Frenchman by your mother's side, because you have kinsfolk engaged, and because it is the Pope and Philip of Spain, as well as the Guises, who are, in fact, battling to stamp out French liberty.

"Of one thing I am sure, my boy--you will disgrace neither an honest English name, nor the French blood in your veins, nor your profession as a Christian and a Protestant. There are Englishmen gaining credit on the Spanish Main, under Drake and Hawkins; there are Englishmen fighting manfully by the side of the Dutch; there are others in the armies of the Protestant princes of Germany; and in none of these matters are they so deeply concerned as you are in the affairs of France and religion.

"I shall miss you, of course, Philip, and that sorely; but I have long seen that this would probably be the upshot of your training and, since I can myself take no share in adventure, beyond the walls of this house, I shall feel that I am living again in you. But, lad, never forget that you are English. You are Philip Fletcher, come of an old Kentish stock; and though you may be living with French kinsfolk and friends, always keep uppermost the fact that you are an Englishman who sympathizes with France, and not a Frenchman with some English blood in your veins. I have given you up greatly to your French relations here; but if you win credit and honour, I would have it won by my son, Philip Fletcher, born in England of an English father, and who will one day be a gentleman and landowner in the county of Kent."

"I sha'n't forget that, father," Philip said earnestly. "I have never regarded myself as in any way French; although speaking the tongue as well as English, and being so much among my mother's friends. But living here with you, where our people have lived so many years; hearing from you the tales from our history; seeing these English fields around me; and being at an English school, among English boys, I have ever felt that I am English, though in no way regretting the Huguenot blood that I inherit from my mother. Believe me, that if I fight in France it will be as an Englishman who has drawn his sword in the quarrel, and rather as one who hates oppression and cruelty than because I have French kinsmen engaged in it."

"That is well, Philip. You may be away for some years, but I trust that, on your return, you will find me sitting here to welcome you back. A creaking wheel lasts long. I have everything to make my life happy and peaceful--the best of wives, a well-ordered farm, and no thought or care as to my worldly affairs--and since it has been God's will that such should be my life, my interest will be wholly centred in you; and I hope to see your children playing round me or, for ought I know, your grandchildren, for we are a long-lived race.

"And now, Philip, you had best go down and see your uncle, and thank him for his good intentions towards you. Tell him that I wholly agree with his plans, and that if he and your aunt will come up this evening, we will enter farther into them."

That evening John Fletcher learned that it was the intention of Gaspard that his wife should accompany Philip.

"Marie yearns to see her people again," he said, "and the present is a good time for her to do so; for when the war once breaks out again, none can say how long it will last or how it will terminate. Her sister and Lucie's, the Countess de Laville, has, as you know, frequently written urgently for Marie to go over and pay her a visit. Hitherto I have never been able to bring myself to spare her, but I feel that this is so good an opportunity that I must let her go for a few weeks.

"Philip could not be introduced under better auspices. He will escort Marie to his aunt's, remain there with her, and then see her on board ship again at La Rochelle; after which, doubtless, he will remain at his aunt's, and when the struggle begins will ride with his cousin Francois. I have hesitated whether I should go, also. But in the first place, my business would get on but badly without me; in the second, although Marie might travel safely enough, I might be arrested were I recognized as one who had left the kingdom contrary to the edicts; and lastly, I never was on very good terms with her family.

"Emilie, in marrying the Count de Laville, made a match somewhat above her own rank; for the Lavilles were a wealthier and more powerful family than that of Charles de Moulins, her father. On the other hand, I was, although of good birth, yet inferior in consideration to De Moulins, although my lands were broader than his. Consequently we saw little of Emilie, after our marriage. Therefore my being with Marie would, in no way, increase the warmth of the welcome that she and Philip will receive. I may say that the estrangement was, perhaps, more my fault than that of the Lavilles. I chose to fancy there was a coolness on their part, which probably existed only in my imagination. Moreover, shortly after my marriage the religious troubles grew serious; and we were all too much absorbed in our own perils, and those of our poorer neighbours, to think of travelling about, or of having family gatherings.

"At any rate, I feel that Philip could not enter into life more favourably than as cousin of Francois de Laville; who is but two years or so his senior, and who will, his mother wrote to Marie, ride behind that gallant gentleman, Francois de la Noue, if the war breaks out again. I am glad to feel confident that Philip will in no way bring discredit upon his relations.

"I shall at once order clothes for him, suitable for the occasion. They will be such as will befit an English gentleman; good in material but sober in colour, for the Huguenots eschew bright hues. I will take his measure, and send up to a friend in London for a helmet, breast, and back pieces, together with offensive arms, sword, dagger, and pistols. I have already written to correspondents, at Southampton and Plymouth, for news as to the sailing of a ship bound for La Rochelle. There he had better take four men into his service, for in these days it is by no means safe to ride through France unattended; especially when one is of the reformed religion. The roads abound with disbanded soldiers and robbers, while in the villages a fanatic might, at any time, bring on a religious tumult. I have many correspondents at La Rochelle, and will write to one asking him to select four stout fellows, who showed their courage in the last war, and can be relied on for good and faithful service. I will also get him to buy horses, and make all arrangements for the journey.

"Marie will write to her sister. Lucie, perhaps, had better write under the same cover; for although she can remember but little of Emilie, seeing that she was fully six years her junior, it would be natural that she should take the opportunity to correspond with her.

"In one respect, Phil," he went on, turning to his nephew, "you will find yourself at some disadvantage, perhaps, among young Frenchmen. You can ride well, and I think can sit a horse with any of them; but of the menage, that is to say, the purely ornamental management of a horse, in which they are most carefully instructed, you know nothing. It is one of the tricks of fashion, of which plain men like myself know but little; and though I have often made inquiries, I have found no one who could instruct you. However, these delicacies are rather for courtly displays than for the rough work of war; though it must be owned that, in single combat between two swordsmen, he who has the most perfect control over his horse, and can make the animal wheel or turn, press upon his opponent, or give way by a mere touch of his leg or hand, possesses a considerable advantage over the man who is unversed in such matters. I hope you will not feel the want of it, and at any rate, it has not been my fault that you have had no opportunity of acquiring the art.

"The tendency is more and more to fight on foot. The duel has taken the place of the combat in the lists, and the pikeman counts for as much in the winning of a battle as the mounted man. You taught us that at Cressy and Agincourt; but we have been slow to learn the lesson, which was brought home to you in your battles with the Scots, and in your own civil struggles. It is the bow and the pike that have made the English soldier famous; while in France, where the feudal system still prevails, horsemen still form a large proportion of our armies; and the jousting lists, and the exercise of the menage, still occupy a large share in the training and amusements of the young men of noble families."

Six weeks later, Philip Fletcher landed at La Rochelle, with his aunt and her French serving maid. When the ship came into port, the clerk of a trader there came on board at once and, on the part of his employer, begged Madame Vaillant and her son to take up their abode at his house; he having been warned of their coming by his valued correspondent, Monsieur Vaillant. A porter was engaged to carry up their luggage to the house, whither the clerk at once conducted them.

From his having lived so long among the Huguenot colony, the scene was less strange to Philip than it would have been to most English lads. La Rochelle was a strongly Protestant city, and the sober-coloured costumes of the people differed but little from those to which he was accustomed in the streets of Canterbury. He himself and his aunt attracted no attention, whatever, from passersby; her costume being exactly similar to those worn by the wives of merchants, while Philip would have passed anywhere as a young Huguenot gentleman, in his doublet of dark puce cloth, slashed with gray, his trunks of the same colour, and long gray hose.

"A proper-looking young gentleman," a market woman said to her daughter, as he passed. "Another two or three years, and he will make a rare defender of the faith. He must be from Normandy, with his fair complexion and light eyes. There are not many of the true faith in the north."

They were met by the merchant at the door of his house.

"I am glad indeed to see you again, Madame Vaillant," he said. "It is some twenty years, now, since you and your good husband and your sister hid here, for three days, before we could smuggle you on board a ship. Ah! Those were bad times; though there have been worse since. But since our people showed that they did not intend, any longer, to be slaughtered unresistingly, things have gone better here, at least; and for the last four years the slaughterings and murders have ceased.

"You are but little changed, madame, since I saw you last."

"I have lived a quiet and happy life, my good Monsieur Bertram; free from all strife and care, save for anxiety about our people here. Why cannot Catholics and Protestants live quietly side by side here, as they do in England?"

"We should ask nothing better, madame."

At this moment, a girl came hurrying down the stairs.

"This is my daughter Jean, madame.

"Why were you not down before, Jean?" he asked sharply. "I told you to place Suzette at the casement, to warn you when our visitors were in sight, so that you should, as was proper, be at the door to meet them. I suppose, instead of that, you had the maid arranging your headgear, or some such worldly folly."

The girl coloured hotly, for her father had hit upon the truth.

"Young people will be young people, Monsieur Bertram," Madame Vaillant said, smiling, "and my husband and I are not of those who think that it is necessary to carry a prim face, and to attire one's self in ugly garments, as a proof of religion. Youth is the time for mirth and happiness, and nature teaches a maiden what is becoming to her; why then should we blame her for setting off the charms God has given her to their best advantage?"

By this time they had reached the upper storey, and the merchant's daughter hastened to relieve Madame Vaillant of her wraps.

"This is my nephew, of whom my husband wrote to you," the latter said to the merchant, when Philip entered the room--he having lingered at the door to pay the porters, and to see that the luggage, which had come up close behind them, was stored.

"He looks active and strong, madame. He has the figure of a fine swordsman."

"He has been well taught, and will do no discredit to our race, Monsieur Bertram. His father is a strong and powerful man, even for an Englishman; and though Philip does not follow his figure, he has something of his strength."

"They are wondrous strong, these Englishmen," the trader said. "I have seen, among their sailors, men who are taller by a head than most of us here, and who look strong enough to take a bull by the horns and hold him. But had it not been for your nephew's fair hair and gray eyes, his complexion, and the smile on his lips--we have almost forgotten how to smile, in France--I should hardly have taken him for an Englishman."

"There is nothing extraordinary in that, Monsieur Bertram, when his mother is French, and he has lived greatly in the society of my husband and myself, and among the Huguenot colony at Canterbury."

"Have you succeeded in getting the horses and the four men for us, Monsieur Bertram?" Philip asked.

"Yes, everything is in readiness for your departure tomorrow. Madame will, I suppose, ride behind you upon a pillion; and her maid behind one of the troopers.

"I have, in accordance with Monsieur Vaillant's instructions, bought a horse, which I think you will be pleased with; for Guise himself might ride upon it, without feeling that he was ill mounted. I was fortunate in lighting on such an animal. It was the property of a young noble, who rode hither from Navarre and was sailing for England. I imagine he bore despatches from the queen to her majesty of England. He had been set upon by robbers on the way. They took everything he possessed, and held him prisoner, doubtless meaning to get a ransom for him; but he managed to slip off while they slept, and to mount his horse, with which he easily left the varlets behind, although they chased him for some distance. So when he came here, he offered to sell his horse to obtain an outfit and money for his voyage; and the landlord of the inn, who is a friend of mine, knowing that I had been inquiring for a good animal, brought him to me, and we soon struck a bargain."

"It was hard on him to lose his horse in that fashion," Philip said; "and I am sorry for it, though I may be the gainer thereby."

"He did not seem to mind much," the merchant said. "Horses are good and abundant in Navarre, and when I said I did not like to take advantage of his strait, he only laughed and said he had three or four others as good at home. He did say, though, that he would like to know if it was to be in good hands. I assured him that on that ground he need not fear; for that I had bought it for a young gentleman, nearly related to the Countess de Laville. He said that was well, and seemed glad, indeed, that it was not to be ridden by one of the brigands into whose hands he fell."

"And the men. Are they trustworthy fellows?"

"They are stout men-at-arms. They are Gascons all, and rode behind Coligny in the war, and according to their own account performed wonders; but as Gascons are given to boasting, I paid not much heed to that. However, they were recommended to me by a friend, a large wine grower, for whom they have been working for the last two years. He says they are honest and industrious, and they are leaving him only because they are anxious for a change and, deeming that troubles were again approaching, wanted to enter the service of some Huguenot lord who would be likely to take the field. He was lamenting the fact to me, when I said that it seemed to me they were just the men I was in search of; and I accordingly saw them, and engaged them on the understanding that, at the end of a month, you should be free to discharge them if you were not satisfied with them; and that equally they could leave your service, if they did not find it suit.

"They have arms, of course, and such armour as they need; and I have bought four serviceable horses for their use, together with a horse to carry your baggage, but which will serve for your body servant.

"I have not found a man for that office. I knew of no one who would, as I thought, suit you; and in such a business it seemed to me better that you should wait, and choose for yourself, for in the matter of servants everyone has his fancies. Some like a silent knave, while others prefer a merry one. Some like a tall proper fellow, who can fight if needs be; others a staid man, who will do his duty and hold his tongue, who can cook a good dinner and groom a horse well. It is certain you will never find all virtues combined. One man may be all that you wish, but he is a liar; another helps himself; a third is too fond of the bottle. In this matter, then, I did not care to take the responsibility, but have left it for you to choose for yourself."

"I shall be more likely to make a mistake than you will, Monsieur Bertram," Philip said with a laugh.

"Perhaps so, but then it will be your own mistake; and a man chafes less, at the shortcomings of one whom he has chosen himself, than at those of one who has, as it were, been forced upon him."

"Well, there will be no hurry in that matter," Philip said. "I can get on well enough without a servant, for a time. Up to the present, I have certainly never given a thought as to what kind of man I should want as a servant; and I should like time to think over a matter which is, from what you say, so important."

"Assuredly it is important, young sir. If you should take the field, you will find that your comfort greatly depends upon it. A sharp, active knave, who will ferret out good quarters for you, turn you out a good meal from anything he can get hold of, bring your horse up well groomed in the morning, and your armour brightly polished; who will not lie to you overmuch, or rob you overmuch, and who will only get drunk at times when you can spare his services. Ah! He would be a treasure to you. But assuredly such a man is not to be found every day."

"And of course," Marie put in, "in addition to what you have said, Monsieur Bertram, it would be necessary that he should be one of our religion, and fervent and strong in the faith."

"My dear lady, I was mentioning possibilities," the trader said. "It is of course advisable that he should be a Huguenot, it is certainly essential that he should not be a Papist; but beyond this we need not inquire too closely. You cannot expect the virtues of an archbishop, and the capacity of a horse boy. If he can find a man embracing the qualities of both, by all means let your son engage him; but as he will require him to be a good cook, and a good groom, and he will not require religious instruction from him, the former points are those on which I should advise him to lay most stress.

"And now, Madame Vaillant, will you let me lead you into the next room where, as my daughter has for some time been trying to make me understand, a meal is ready? And I doubt not that you are also ready; for truly those who travel by sea are seldom able to enjoy food, save when they are much accustomed to voyaging. Though they tell me that, after a time, even those with the most delicate stomachs recover their appetites, and are able to enjoy the rough fare they get on board a ship."

After the meal was over, the merchant took Philip to the stables, where the new purchases had been put up. The men were not there, but the ostler brought out Philip's horse, with which he was delighted.

"He will not tire under his double load," the merchant said; "and with only your weight upon him, a foeman would be well mounted, indeed, to overtake you."

"I would rather that you put it, Monsieur Bertram, that a foeman needs be well mounted to escape me."

"Well, I hope it will be that way," his host replied, smiling. "But in fighting such as we have here, there are constant changes. The party that is pursued one day is the pursuer a week later; and of the two, you know, speed is of much more importance in flight than in pursuit. If you cannot overtake a foe, well, he gets away, and you may have better fortune next time; but if you can't get away from a foe, the chances are you may never have another opportunity of doing so."

"Perhaps you are right. In fact, now I think of it, I am sure you are; though I hope it will not often happen that we shall have to depend for safety on the speed of our horses. At any rate, I am delighted with him, Monsieur Bertram; and I thank you greatly for procuring so fine an animal for me. If the four men turn out to be as good, of their kind, as the horse, I shall be well set up, indeed."

Early the next morning the four men came round to the merchant's, and Philip went down with him into the entry hall where they were. He was well satisfied with their appearance. They were stout fellows, from twenty-six to thirty years old. All were soberly dressed, and wore steel caps and breast pieces, and carried long swords by their sides. In spite of the serious expression of their faces, Philip saw that all were in high, if restrained, spirits at again taking service.

"This is your employer, the Sieur Philip Fletcher. I have warranted that he shall find you good and true men, and I hope you will do justice to my recommendation."

"We will do our best," Roger, the eldest of the party, said. "We are all right glad to be moving again. It is not as if we had been bred on the soil here, and a man never takes to a strange place as to one he was born in."

"You are Gascons, Maitre Bertram tells me," Philip said.

"Yes, sir. We were driven out from there ten years ago, when the troubles were at their worst. Our fathers were both killed, and we travelled with our mothers and sisters by night, through the country, till we got to La Rochelle."

"You say both your fathers. How are you related to each other?"

"Jacques and I are brothers," Roger said, touching the youngest of the party on his shoulder. "Eustace and Henri are brothers, and are our cousins. Their father and ours were brothers. When the troubles broke out, we four took service with the Count de Luc, and followed him throughout the war. When it was over we came back here. Our mothers had married again. Some of our sisters had taken husbands, too. Others were in service. Therefore we remained here rather than return to Gascony, where our friends and relations had all been either killed or dispersed.

"We were lucky in getting employment together, but were right glad when we heard that there was an opening again for service. For the last two years we have been looking forward to it; for as everyone sees, it cannot be long before the matter must be fought out again. And in truth, we have been wearying for the time to come; for after having had a year of fighting, one does not settle down readily to tilling the soil.

"You will find that you can rely on us, sir, for faithful service. We all bore a good reputation as stout fighters and, during the time we were in harness before, we none of us got into trouble for being overfond of the wine pots."

"I think you will suit me very well," Philip said, "and I hope that my service will suit you. Although an Englishman by birth and name, my family have suffered persecution here as yours have done, and I am as warmly affected to the Huguenot cause as yourselves. If there is danger you will not find me lacking in leading you, and so far as I can I shall try to make my service a comfortable one, and to look after your welfare.

"We shall be ready to start in half an hour, therefore have the horses round at the door in that time. One of the pillions is to be placed on my own horse. You had better put the other for the maid behind your saddle, Roger; you being, I take it, the oldest of your party, had better take charge of her."

The men saluted and went out.

"I like their looks much," Philip said to the merchant. "Stout fellows and cheerful, I should say. Like my aunt, I don't see why we should carry long faces, Monsieur Bertram, because we have reformed our religion; and I believe that a light heart and good spirits will stand wear and tear better than a sad visage."

The four men were no less pleased with their new employer.

"That is a lad after my own heart," Roger said, as they went out. "Quick and alert, pleasant of face; and yet, I will be bound, not easily turned from what he has set his mind to. He bears himself well, and I doubt not can use his weapons. I don't know what stock he comes from, on this side, but I warrant it is a good one.

"He will make a good master, lads. I think that, as he says, he will be thoughtful as to our comforts, and be pleasant and cheerful with us; but mind you, he will expect the work to be done, and you will find that there is no trifling with him."

Chapter 3: In A French Chateau.

The three days' ride to the chateau of the Countess de Laville was marked by no incident. To Philip it was an exceedingly pleasant one. Everything was new to him; the architecture of the churches and villages, the dress of the people, their modes of agriculture, all differing widely from those to which he was accustomed. In some villages the Catholics predominated, and here the passage of the little party was regarded with frowning brows and muttered threats; by the Huguenots they were saluted respectfully, and if they halted, many questions were asked their followers as to news about the intentions of the court, the last rumours as to the attitude of Conde, and the prospects of a continuance of peace.

Here, too, great respect was paid to Marie and Philip when it was known they were relatives of the Countess de Laville, and belonged to the family of the De Moulins. Emilie had for some time been a widow--the count, her husband, having fallen at the battle of Dreux, at the end of the year 1562--but being an active and capable woman, she had taken into her hands the entire management of the estates, and was one of the most influential among the Huguenot nobles of that part of the country.

From their last halting place, Marie Vaillant sent on a letter by one of the men to her sister, announcing their coming. She had written on her landing at La Rochelle, and they had been met on their way by a messenger from the countess, expressing her delight that her sister had at last carried out her promise to visit her, and saying that Francois was looking eagerly for the coming of his cousin.

The chateau was a semi-fortified building, capable of making a stout resistance against any sudden attack. It stood on the slope of a hill, and Philip felt a little awed at its stately aspect as they approached it. When they were still a mile away, a party of horsemen rode out from the gateway, and in a few minutes their leader reined up his horse in front of them and, springing from it, advanced towards Philip, who also alighted and helped his aunt to dismount.

"My dear aunt," the young fellow said, doffing his cap, "I am come in the name of my mother to greet you, and to tell you how joyful she is that you have, at last, come back to us.

"This is my Cousin Philip, of course; though you are not what I expected to see. My mother told me that you were two years' my junior, and I had looked to find you still a boy; but, by my faith, you seem to be as old as I am. Why, you are taller by two inches, and broader and stronger too, I should say. Can it be true that you are but sixteen?"

"That is my age, Cousin Francois; and I am, as you expected, but a boy yet and, I can assure you, no taller or broader than many of my English schoolfellows of the same age."

"But we must not delay, aunt," Francois said, turning again to her. "My mother's commands were urgent, that I was not to delay a moment in private talk with you, but to bring you speedily on to her; therefore I pray you to mount again and ride on with me, for doubtless she is watching impatiently now, and will chide me rarely, if we linger."

Accordingly the party remounted at once, and rode forward to the chateau. A dozen men-at-arms were drawn up at the gate and, on the steps of the entrance from the courtyard into the chateau itself, the countess was standing. Francois leapt from his horse, and was by the side of his aunt as Philip reined in his horse. Taking his hand, she sprang lightly from the saddle, and in a moment the two sisters fell into each others' arms.

It was more than twenty years since they last met, but time had dealt gently with them both. The countess had changed least. She was two or three years older than Marie, was tall, and had been somewhat stately even as a girl. She had had many cares, but her position had always been assured; as the wife of a powerful noble she had been accustomed to be treated with deference and respect, and although the troubles of the times and the loss of her husband had left their marks, she was still a fair and stately woman at the age of forty-three. Marie, upon the other hand, had lived an untroubled life for the past twenty years. She had married a man who was considered beneath her, but the match had been in every way a happy one. Her husband was devoted to her, and the expression of her face showed that she was a thoroughly contented and happy woman.

"You are just what I fancied you would be, Marie, a quiet little home bird, living in your nest beyond the sea, and free from all the troubles and anxieties of our unhappy country. You have been good to write so often, far better than I have been; and I seem to know all about your quiet, well-ordered home, and your good husband and his business that flourishes so. I thought you were a little foolish in your choice, and that our father was wrong in mating you as he did; but it has turned out well, and you have been living in quiet waters, while we have been encountering a sea of troubles.