« back

Captain Mayne Reid

"The Bush Boys"

Chapter One.

The Boors.

Hendrik Von Bloom was a boor.

My young English reader, do not suppose that I mean any disrespect to Mynheer Von Bloom, by calling him a “boor.” In our good Cape colony a “boor” is a farmer. It is no reproach to be called a farmer. Von Bloom was one—a Dutch farmer of the Cape—a boor.

The boors of the Cape colony have figured very considerably in modern history. Although naturally a people inclined to peace, they have been forced into various wars, both with native Africans and Europeans; and in these wars they have acquitted themselves admirably, and given proofs that a pacific people when need be can fight just as well as those who are continually exulting in the ruffian glory of the soldier.

But the boors have been accused of cruelty in their wars—especially those carried on against the native races. In an abstract point of view the accusation might appear just. But when we come to consider the provocation, received at the hands of these savage enemies, we learn to look more leniently upon the conduct of the Cape Dutch. It is true they reduced the yellow Hottentots to a state of slavery; but at that same time, we, the English, were transporting ship-loads of black Guineamen across the Atlantic, while the Spaniards and Portuguese were binding the Red men of America in fetters as tight and hard.

Another point to be considered is the character of the natives with whom the Dutch boors had to deal. The keenest cruelty inflicted upon them by the colonists was mercy, compared with the treatment which these savages had to bear at the hands of their own despots.

This does not justify the Dutch for having reduced the Hottentots to a state of slavery; but, all circumstances considered, there is no one of the maritime nations who can gracefully accuse them of cruelty. In their dealings with the aborigines of the Cape, they have had to do with savages of a most wicked and degraded stamp; and the history of colonisation, under such circumstances, could not be otherwise then full of unpleasant episodes.

Young reader, I could easily defend the conduct of the boors of Cape colony, but I have not space here. I can only give you my opinion; and that is, that they are a brave, strong, healthy, moral, peace-loving, industrious race—lovers of truth, and friends to republican freedom—in short, a noble race of men.

Is it likely, then, when I called Hendrik Von Bloom a boor, that I meant him any disrespect? Quite the contrary.

But Mynheer Hendrik had not always been a boor. He could boast of a somewhat higher condition—that is, he could boast of a better education than the mere Cape farmer usually possesses, as well as some experience in wielding the sword. He was not a native of the colony, but of the mother country; and he had found his way to the Cape not as a poor adventurer seeking his fortune, but as an officer in a Dutch regiment then stationed there.

His soldier-service in the colony was not of long duration. A certain cherry-cheeked, flaxen-haired Gertrude—the daughter of a rich boor—had taken a liking to the young lieutenant; and he in his turn became vastly fond of her. The consequence was, that they got married. Gertrude’s father dying shortly after, the large farm, with its full stock of horses, and Hottentots, broad-tailed sheep, and long-horned oxen, became hers. This was an inducement for her soldier-husband to lay down the sword and turn “vee-boor,” or stock farmer, which he consequently did.

These incidents occurred many years previous to the English becoming masters of the Cape colony. When that event came to pass, Hendrik Von Bloom was already a man of influence in the colony and “field-cornet” of his district, which lay in the beautiful county of Graaf Reinet. He was then a widower, the father of a small family. The wife whom he had fondly loved,—the cherry-cheeked, flaxen-haired Gertrude—no longer lived.

History will tell you how the Dutch colonists, discontented with English rule, rebelled against it. The ex-lieutenant and field-cornet was one of the most prominent among these rebels. History will also tell you how the rebellion was put down; and how several of those compromised were brought to execution. Von Bloom escaped by flight; but his fine property in the Graaf Reinet was confiscated and given to another.

Many years after we find him living in a remote district beyond the great Orange River, leading the life of a “trek-boor,”—that is, a nomade farmer, who has no fixed or permanent abode, but moves with his flocks from place to place, wherever good pastures and water may tempt him.

From about this time dates my knowledge of the field-cornet and his family. Of his history previous to this I have stated all I know, but for a period of many years after I am more minutely acquainted with it. Most of its details I received from the lips of his own son, I was greatly interested, and indeed instructed, by them. They were my first lessons in African zoology.

Believing, boy reader, that they might also instruct and interest you, I here lay them before you. You are not to regard them as merely fanciful. The descriptions of the wild creatures that play their parts in this little history, as well as the acts, habits, and instincts assigned to them, you may regard as true to Nature. Young Von Bloom was a student of Nature, and you may depend upon the fidelity of his descriptions.

Disgusted with politics, the field-cornet now dwelt on the remote frontier—in fact, beyond the frontier, for the nearest settlement was an hundred miles off. His “kraal” was in a district bordering the great Kalihari desert—the Saära of Southern Africa. The region around, for hundreds of miles, was uninhabited, for the thinly-scattered, half-human Bushmen who dwelt within its limits, hardly deserved the name of inhabitants any more than the wild beasts that howled around them.

I have said that Von Bloom now followed the occupation of a “trek-boor.” Farming in the Cape colony consists principally in the rearing of horses, cattle, sheep, and goats; and these animals form the wealth of the boor. But the stock of our field-cornet was now a very small one. The proscription had swept away all his wealth, and he had not been fortunate in his first essays as a nomade grazier. The emancipation law, passed by the British Government, extended not only to the Negroes of the West India Islands, but also to the Hottentots of the Cape; and the result of it was that the servants of Mynheer Von Bloom had deserted him. His cattle, no longer properly cared for, had strayed off. Some of them fell a prey to wild beasts—some died of the murrain. His horses, too, were decimated by that mysterious disease of Southern Africa, the “horse-sickness;” while his sheep and goats were continually being attacked and diminished in numbers by the earth-wolf, the wild hound, and the hyena. A series of losses had he suffered until his horses, oxen, sheep, and goats, scarce counted altogether an hundred head. A very small stock for a vee-boor, or South African grazier.

Withal our field-cornet was not unhappy. He looked around upon his three brave sons—Hans, Hendrik, and Jan. He looked upon his cherry-cheeked, flaxen-haired daughter, Gertrude, the very type and image of what her mother had been. From these he drew the hope of a happier future.

His two eldest boys were already helps to him in his daily occupations; the youngest would soon be so likewise. In Gertrude,—or “Trüey,” as she was endearingly styled,—he would soon have a capital housekeeper. He was not unhappy therefore; and if an occasional sigh escaped him, it was when the face of little Trüey recalled the memory of that Gertrude who was now in heaven.

But Hendrik Von Bloom was not the man to despair. Disappointments had not succeeded in causing his spirits to droop. He only applied himself more ardently to the task of once more building up his fortune.

For himself he had no ambition to be rich. He would have been contented with the simple life he was leading, and would have cared but little to increase his wealth. But other considerations weighed upon his mind—the future of his little family. He could not suffer his children to grow up in the midst of the wild plains without education.

No; they must one day return to the abodes of men, to act their part in the drama of social and civilised life. This was his design.

But how was this design to be accomplished? Though his so-called act of treason had been pardoned, and he was now free to return within the limits of the colony, he was ill prepared for such a purpose. His poor wasted stock would not suffice to set him up within the settlements. It would scarce keep him a month. To return would be to return a beggar!

Reflections of this kind sometimes gave him anxiety. But they also added energy to his disposition, and rendered him more eager to overcome the obstacles before him.

During the present year he had been very industrious. In order that his cattle should be provided for in the season of winter he had planted a large quantity of maize and buckwheat, and now the crops of both were in the most prosperous condition. His garden, too, smiled, and promised a profusion of fruits, and melons, and kitchen vegetables. In short, the little homestead where he had fixed himself for a time, was a miniature oasis; and he rejoiced day after day, as his eyes rested upon the ripening aspect around him. Once more he began to dream of prosperity—once more to hope that his evil fortunes had come to an end.

Alas! It was a false hope. A series of trials yet awaited him—a series of misfortunes that deprived him of almost everything he possessed, and completely changed his mode of existence.

Perhaps these occurrences could hardly be termed misfortunes, since in the end they led to a happy result.

But you may judge for yourself, boy reader, after you have heard the “history and adventures” of the “trek-boor” and his family.

Chapter Two.

The “Kraal.”

The ex-field-cornet was seated in front of his kraal—for such is the name of a South African homestead. From his lips protruded a large pipe, with its huge bowl of meerschaum. Every boor is a smoker.

Notwithstanding the many losses and crosses of his past life, there was contentment in his eye. He was gratified by the prosperous appearance of his crops. The maize was now “in the milk,” and the ears, folded within the papyrus-like husks, looked full and large. It was delightful to hear the rustling of the long green blades, and see the bright golden tassels waving in the breeze. The heart of the farmer was glad as his eye glanced over his promising crop of “mealies.” But there was another promising crop that still more gladdened his heart—his fine children. There they are—all around him.

Hans—the oldest—steady, sober Hans, at work in the well-stocked garden; while the diminutive but sprightly imp Jan, the youngest, is looking on, and occasionally helping his brother. Hendrik—the dashing Hendrik, with bright face and light curling hair—is busy among the horses, in the “horse-kraal;” and Trüey—the beautiful, cherry-cheeked, flaxen-haired Trüey—is engaged with her pet—a fawn of the springbok gazelle—whose bright eyes rival her own in their expression of innocence and loveliness.

Yes, the heart of the field-cornet is glad as he glances from one to the other of these his children—and with reason. They are all fair to look upon,—all give promise of goodness. If their father feels an occasional pang, it is, as we have already said, when his eye rests upon the cherry-cheeked, flaxen-haired Gertrude.

But time has long since subdued that grief to a gentle melancholy. Its pang is short-lived, and the face of the field-cornet soon lightens up again as he looks around upon his dear children, so full of hope and promise.

Hans and Hendrik are already strong enough to assist him in his occupations,—in fact, with the exception of “Swartboy,” they are the only help he has.

Who is Swartboy?

Look into the horse-kraal, and you will there see Swartboy engaged, along with his young master Hendrik, in saddling a pair of horses. You may notice that Swartboy appears to be about thirty years old, and he is full that; but if you were to apply a measuring rule to him, you would find him not much over four feet in height! He is stoutly built however, and would measure better in a horizontal direction. You may notice that he is of a yellow complexion, although his name might lead you to fancy he was black—for “Swartboy” means “black-boy.” You may observe that his nose is flat and sunk below the level of his cheeks; that his cheeks are prominent, his lips very thick, his nostrils wide, his face beardless, and his head almost hairless—for the small kinky wool-knots thinly-scattered over his skull can scarcely be designated hair. You may notice, moreover, that his head is monstrously large, with ears in proportion, and that the eyes are set obliquely, and have a Chinese expression. You may notice about Swartboy all those characteristics that distinguish the “Hottentots” of South Africa.

Yet Swartboy is not a Hottentot—though he is of the same race. He is a Bushman.

How came this wild Bushman into the service of the ex-field-cornet Von Bloom? About that there is a little romantic history. Thus:—

Among the savage tribes of Southern Africa there exists a very cruel custom,—that of abandoning their aged or infirm, and often their sick or wounded, to die in the desert. Children leave their parents behind them, and the wounded are often forsaken by their comrades with no other provision made for them beyond a day’s food and a cup of water!

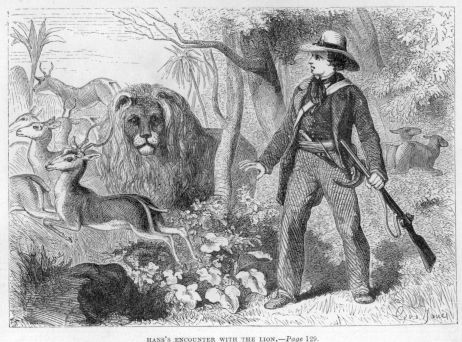

The Bushman Swartboy had been the victim of this custom. He had been upon a hunting excursion with some of his own kindred, and had been sadly mangled by a lion. His comrades, not expecting him to live, left him on the plain to die; and most certainly would he have perished had it not been for our field-cornet. The latter, as he was “trekking” over the plains, found the wounded Bushman, lifted him into his wagon, carried him on to his camp, dressed his wounds, and nursed him till he became well. That is how Swartboy came to be in the service of the field-cornet.

Though gratitude is not a characteristic of his race, Swartboy was not ungrateful. When all the other servants ran away, he remained faithful to his master; and since that time had been a most efficient and useful hand. In fact, he was now the only one left, with the exception of the girl, Totty—who was, of course, a Hottentot; and much about the same height, size, and colour, as Swartboy himself.

We have said that Swartboy and the young Hendrik were saddling a pair of horses. As soon as they had finished that job, they mounted them, and riding out of the kraal, took their way straight across the plain. They were followed by a couple of strong, rough-looking dogs.

Their purpose was to drive home the oxen and the other horses that were feeding a good distance off. This they were in the habit of doing every evening at the same hour,—for in South Africa it is necessary to shut up all kinds of live-stock at night, to protect them from beasts of prey. For this purpose are built several enclosures with high walls,—“kraals,” as they are called,—a word of the same signification as the Spanish “corral,” and I fancy introduced into Africa by the Portuguese—since it is not a native term.

These kraals are important structures about the homestead of a boor, almost as much so as his own dwelling-house, which of itself also bears the name of “kraal.”

As young Hendrik and Swartboy rode off for the horses and cattle, Hans, leaving his work in the garden, proceeded to collect the sheep and drive them home. These browsed in a different direction; but, as they were near, he went afoot, taking little Jan along with him.

Trüey having tied her pet to a post, had gone inside the house to help Totty in preparing the supper. Thus the field-cornet was left to himself and his pipe, which he still continued to smoke.

He sat in perfect silence, though he could scarce restrain from giving expression to the satisfaction he felt at seeing his family thus industriously employed. Though pleased with all his children, it must be confessed he had some little partiality for the dashing Hendrik, who bore his own name, and who reminded him more of his own youth than any of the others. He was proud of Hendrik’s gallant horsemanship, and his eyes followed him over the plain until the riders were nearly a mile off, and already mixing among the cattle.

At this moment an object came under the eyes of Von Bloom, that at once arrested his attention. It was a curious appearance along the lower part of the sky, in the direction in which Hendrik and Swartboy had gone, but apparently beyond them. It resembled a dun-coloured mist or smoke, as if the plain at a great distance was on fire!

Could that be so? Had some one fired the karoo bushes? Or was it a cloud of dust?

The wind was hardly strong enough to raise such a dust, and yet it had that appearance. Was it caused by animals? Might it not be the dust raised by a great herd of antelopes,—a migration of the springboks, for instance? It extended for miles along the horizon, but Von Bloom knew that these creatures often travel in flocks of greater extent than miles. Still he could not think it was that.

He continued to gaze at the strange phenomenon, endeavouring to account for it in various ways. It seemed to be rising higher against the blue sky—now resembling dust, now like the smoke of a widely-spread conflagration, and now like a reddish cloud. It was in the west, and already the setting sun was obscured by it. It had passed over the sun’s disc like a screen, and his light no longer fell upon the plain. Was it the forerunner of some terrible storm?—of an earthquake?

Such a thought crossed the mind of the field-cornet. It was not like an ordinary cloud,—it was not like a cloud of dust,—it was not like smoke. It was like nothing he had ever witnessed before. No wonder that he became anxious and apprehensive.

All at once the dark-red mass seemed to envelope the cattle upon the plain, and these could be seen running to and fro as if affrighted. Then the two riders disappeared under its dun shadow!

Von Bloom rose to his feet, now seriously alarmed. What could it mean?

The exclamation to which he gave utterance brought little Trüey and Totty from the house; and Hans with Jan had now got back with the sheep and goats. All saw the singular phenomenon, but none of them could tell what it was. All were in a state of alarm.

As they stood gazing, with hearts full of fear, the two riders appeared coming out of the cloud, and then they were seen to gallop forward over the plain in the direction of the house. They came on at full speed, but long before they had got near, the voice of Swartboy could be heard crying out,—

“Baas Von Bloom! da springhaans are comin!—da springhaan!—da springhaan!”

Chapter Three.

The “Springhaan.”

“Ah! the springhaan!” cried Von Bloom, recognising the Dutch name for the far-famed migratory locust.

The mystery was explained. The singular cloud that was spreading itself over the plain was neither more nor less than a flight of locusts!

It was a sight that none of them, except Swartboy, had ever witnessed before. His master had often seen locusts in small quantities, and of several species,—for there are many kinds of these singular insects in South Africa. But that which now appeared was a true migratory locust (Gryllus devastatorius); and upon one of its great migrations—an event of rarer occurrence than travellers would have you believe.

Swartboy knew them well; and, although he announced their approach in a state of great excitement, it was not the excitement of terror.

Quite the contrary. His great thick lips were compressed athwart his face in a grotesque expression of joy. The instincts of his wild race were busy within him. To them a flight of locusts is not an object of dread, but a source of rejoicing—their coming as welcome as a take of shrimps to a Leigh fisherman, or harvest to the husbandman.

The dogs, too, barked and howled with joy, and frisked about as if they were going out upon a hunt. On perceiving the cloud, their instinct enabled them easily to recognise the locusts. They regarded them with feelings similar to those that stirred Swartboy—for both dogs and Bushmen eat the insects with avidity!

At the announcement that it was only locusts, all at once recovered from their alarm. Little Trüey and Jan laughed, clapped their hands, and waited with curiosity until they should come nearer. All had heard enough of locusts to know that they were only grasshoppers that neither bit nor stung any one, and therefore no one was afraid of them.

Even Von Bloom himself was at first very little concerned about them. After his feelings of apprehension, the announcement that it was a flight of locusts was a relief, and for a while he did not dwell upon the nature of such a phenomenon, but only regarded it with feelings of curiosity.

Of a sudden his thoughts took a new direction. His eye rested upon his fields of maize and buckwheat, upon his garden of melons, and fruits, and vegetables: a new alarm seized upon him; the memory of many stories which he had heard in relation to these destructive creatures rushed into his mind, and as the whole truth developed itself, he turned pale, and uttered new exclamations of alarm.

The children changed countenance as well. They saw that their father suffered; though they knew not why. They gathered inquiringly around him.

“Alas! alas! Lost! lost!” exclaimed he; “yes, all our crop—our labour of the year—gone, gone! O my dear children!”

“How lost, father?—how gone?” exclaimed several of them in a breath.

“See the springhaan! they will eat up our crop—all—all!”

“’Tis true, indeed,” said Hans, who being a great student had often read accounts of the devastations committed by the locusts.

The joyous countenances of all once more wore a sad expression, and it was no longer with curiosity that they gazed upon the distant cloud, that so suddenly had clouded their joy.

Von Bloom had good cause for dread. Should the swarm come on, and settle upon his fields, farewell to his prospects of a harvest. They would strip the verdure from his whole farm in a twinkling. They would leave neither seed, nor leaf, nor stalk, behind them.

All stood watching the flight with painful emotions. The swarm was still a full half-mile distant. They appeared to be coming no nearer,—good!

A ray of hope entered the mind of the field-cornet. He took off his broad felt hat, and held it up to the full stretch of his arm. The wind was blowing from the north, and the swarm was directly to the west of the kraal. The cloud of locusts had approached from the north, as they almost invariably do in the southern parts of Africa.

“Yes,” said Hendrik, who having been in their midst could tell what way they were drifting, “they came down upon us from a northerly direction. When we headed our horses homewards, we soon galloped out from them, and they did not appear to fly after us; I am sure they were passing southwards.”

Von Bloom entertained hopes that as none appeared due north of the kraal, the swarm might pass on without extending to the borders of his farm. He knew that they usually followed the direction of the wind. Unless the wind changed they would not swerve from their course.

He continued to observe them anxiously. He saw that the selvedge of the cloud came no nearer. His hopes rose. His countenance grew brighter. The children noticed this and were glad, but said nothing. All stood silently watching.

An odd sight it was. There was not only the misty swarm of the insects to gaze upon. The air above them was filled with birds—strange birds and of many kinds. On slow, silent wing soared the brown “oricou,” the largest of Africa’s vultures; and along with him the yellow “chasse fiente,” the vulture of Kolbé. There swept the bearded “lamvanger,” on broad extended wings. There shrieked the great “Caffre eagle,” and side by side with him the short-tailed and singular “bateleur.” There, too, were hawks of different sizes and colours, and kites cutting through the air, and crows and ravens, and many species of insectivora. But far more numerous than all the rest could be seen the little springhaan-vogel, a speckled bird of nearly the size and form of a swallow. Myriads of these darkened the air above—hundreds of them continually shooting down among the insects, and soaring up again, each with a victim in its beak. “Locust-vultures” are these creatures named, though not vultures in kind. They feed exclusively on these insects, and are never seen where the locusts are not. They follow them through all their migrations, building their nests, and rearing their young, in the midst of their prey!

It was, indeed, a curious sight to look upon, that swarm of winged insects, and their numerous and varied enemies; and all stood gazing upon it with feelings of wonder. Still the living cloud approached no nearer, and the hopes of Von Bloom continued to rise.

The swarm kept extending to the south—in fact, it now stretched along the whole western horizon; and all noticed that it was gradually getting lower down—that is, its top edge was sinking in the heavens. Were the locusts passing off to the west? No.

“Da am goin’ roost for da nacht—now we’ll get ’em in bagfull,” said Swartboy, with a pleased look; for Swartboy was a regular locust-eater, as fond of them as either eagle or kite,—ay, as the “springhaan-vogel” itself.

It was as Swartboy had stated. The swarm was actually settling down on the plain.

“Can’t fly without sun,” continued the Bushman. “Too cold now. Dey go dead till da mornin.”

And so it was. The sun had set. The cool breeze weakened the wings of the insect travellers, and they were compelled to make halt for the night upon the trees, bushes, and grass.

In a few minutes the dark mist that had hid the blue rim of the sky, was seen no more; but the distant plain looked as if a fire had swept over it. It was thickly covered with the bodies of the insects, that gave it a blackened appearance, as far as the eye could reach.

The attendant birds, perceiving the approach of night, screamed for awhile, and then scattered away through the heavens. Some perched upon the rocks, while others went to roost among the low thickets of mimosa; and now for a short interval both earth and air were silent.

Von Bloom now bethought him of his cattle. Their forms were seen afar off in the midst of the locust-covered plain.

“Let ’em feed um little while, baas,” suggested Swartboy.

“On what?” inquired his master. “Don’t you see the grass is covered!”

“On de springhaan demself, baas,” replied the Bushman; “good for fatten big ox—better dan grass—ya, better dan mealies.”

But it was too late to leave the cattle longer out upon the plain. The lions would soon be abroad—the sooner because of the locusts, for the king of the beasts does not disdain to fill his royal stomach with these insects—when he can find them.

Von Bloom saw the necessity of bringing his cattle at once to their kraal.

A third horse was saddled, which the field-cornet himself mounted, and rode off, followed by Hendrik and Swartboy.

On approaching the locusts they beheld a singular sight. The ground was covered with these reddish-brown creatures, in some spots to the depth of several inches. What bushes there were were clustered with them,—all over the leaves and branches, as if swarms of bees had settled upon them. Not a leaf or blade of grass that was not covered with their bodies!

They moved not, but remained silent, as if torpid or asleep. The cold of the evening had deprived them of the power of flight.

What was strangest of all to the eyes of Von Bloom and Hendrik, was the conduct of their own horses and cattle. These were some distance out in the midst of the sleeping host; but instead of being alarmed at their odd situation, they were greedily gathering up the insects in mouthfuls, and crunching them as though they had been corn!

It was with some difficulty that they could be driven off; but the roar of a lion, that was just then heard over the plain, and the repeated application of Swartboy’s jambok, rendered them more tractable, and at length they suffered themselves to be driven home, and lodged within their kraals.

Swartboy had provided himself with a bag, which he carried back full of locusts.

It was observed that in collecting the insects into the bag, he acted with some caution, handling them very gingerly, as if he was afraid of them. It was not them he feared, but snakes, which upon such occasions are very plenteous, and very much to be dreaded—as the Bushman from experience well knew.

Chapter Four.

A talk about Locusts.

It was a night of anxiety in the kraal of the field-cornet. Should the wind veer round to the west, to a certainty the locusts would cover his land in the morning, and the result would be the total destruction of his crops. Perhaps worse than that. Perhaps the whole vegetation around—for fifty miles or more—might be destroyed; and then how would his cattle be fed? It would be no easy matter even to save their lives. They might perish before he could drive them to any other pasturage!

Such a thing was by no means uncommon or improbable. In the history of the Cape colony many a boor had lost his flocks in this very way. No wonder there was anxiety that night in the kraal of the field-cornet.

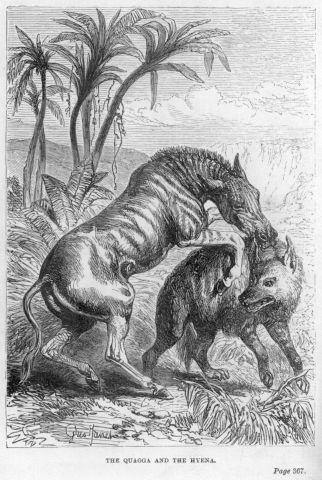

At intervals Von Bloom went out to ascertain whether there was any change in the wind. Up to a late hour he could perceive none. A gentle breeze still blew from the north—from the great Kalihari desert—whence, no doubt, the locusts had come. The moon was bright, and her light gleamed over the host of insects that darkly covered the plain. The roar of the lion could be heard mingling with the shrill scream of the jackal and the maniac laugh of the hyena. All these beasts, and many more, were enjoying a plenteous repast.

Perceiving no change in the wind, Von Bloom became less uneasy, and they all conversed freely about the locusts. Swartboy took a leading part in this conversation, as he was better acquainted with the subject than any of them. It was far from being the first flight of locusts Swartboy had seen, and many a bushel of them had he eaten. It was natural to suppose, therefore, that he knew a good deal about them.

He knew not whence they came. That was a point about which Swartboy had never troubled himself. The learned Hans offered an explanation of their origin.

“They come from the desert,” said he. “The eggs from which they are produced, are deposited in the sands or dust; where they lie until rain falls, and causes the herbage to spring up. Then the locusts are hatched, and in their first stage are supported upon this herbage. When it becomes exhausted, they are compelled to go in search of food. Hence these ‘migrations,’ as they are called.”

This explanation seemed clear enough.

“Now I have heard,” said Hendrik, “of farmers kindling fires around their crops to keep off the locusts. I can’t see how fires would keep them off—not even if a regular fence of fire were made all round a field. These creatures have wings, and could easily fly over the fires.”

“The fires,” replied Hans, “are kindled, in order that the smoke may prevent them from alighting; but the locusts to which these accounts usually refer are without wings, called voetgangers (foot-goers). They are, in fact, the larvae of these locusts, before they have obtained their wings. These have also their migrations, that are often more destructive than those of the perfect insects, such as we see here. They proceed over the ground by crawling and leaping like grasshoppers; for, indeed, they are grasshoppers—a species of them. They keep on in one direction, as if they were guided by instinct to follow a particular course. Nothing can interrupt them in their onward march unless the sea or some broad and rapid river. Small streams they can swim across; and large ones, too, where they run sluggishly; walls and houses they can climb—even the chimneys—going straight over them; and the moment they have reached the other side of any obstacle, they continue straight onward in the old direction.

“In attempting to cross broad rapid rivers, they are drowned in countless myriads, and swept off to the sea. When it is only a small migration, the farmers sometimes keep them off by means of fires, as you have heard. On the contrary, when large numbers appear, even the fires are of no avail.”

“But how is that, brother?” inquired Hendrik. “I can understand how fires would stop the kind you speak of, since you say they are without wings. But since they are so, how do they get through the fires? Jump them?”

“No, not so,” replied Hans. “The fires are built too wide and large for that.”

“How then, brother?” asked Hendrik. “I’m puzzled.”

“So am I,” said little Jan.

“And I,” added Trüey.

“Well, then,” continued Hans, “millions of the insects crawl into the fires and put them out!”

“Ho!” cried all in astonishment. “How? Are they not burned?”

“Of course,” replied Hans. “They are scorched and killed—myriads of them quite burned up. But their bodies crowded thickly on the fires choke them out. The foremost ranks of the great host thus become victims, and the others pass safely across upon the holocaust thus made. So you see, even fires cannot stop the course of the locusts when they are in great numbers.

“In many parts of Africa, where the natives cultivate the soil, as soon as they discover a migration of these insects, and perceive that they are heading in the direction of their fields and gardens, quite a panic is produced among them. They know that they will lose their crops to a certainty, and hence dread a visitation of locusts as they would an earthquake, or some other great calamity.”

“We can well understand their feelings upon such an occasion,” remarked Hendrik, with a significant look.

“The flying locusts,” continued Hans, “seem less to follow a particular direction than their larvae. The former seem to be guided by the wind. Frequently this carries them all into the sea, where they perish in vast numbers. On some parts of the coast their dead bodies have been found washed back to land in quantities incredible. At one place the sea threw them upon the beach, until they lay piled up in a ridge four feet in height, and fifty miles in length! It has been asserted by several well-known travellers that the effluvium from this mass tainted the air to such an extent that it was perceived one hundred and fifty miles inland!”

“Heigh!” exclaimed little Jan. “I didn’t think anybody had so good a nose.”

At little Jan’s remark there was a general laugh. Von Bloom did not join in their merriment. He was in too serious a mood just then.

“Papa,” inquired little Trüey, perceiving that her father did not laugh, and thinking to draw him into the conversation,—“Papa! were these the kind of locusts eaten by John the Baptist when in the desert? His food, the Bible says, was ‘locusts and wild honey.’”

“I believe these are the same,” replied the father.

“I think, papa,” modestly rejoined Hans, “they are not exactly the same, but a kindred species. The locust of Scripture was the true Gryllus migratorius, and different from those of South Africa, though very similar in its habits. But,” continued he, “some writers dispute that point altogether. The Abyssinians say it was beans of the locust-tree, and not insects, that were the food of Saint John.”

“What is your own opinion, Hans?” inquired Hendrik, who had a great belief in his brother’s book-knowledge.

“Why, I think,” replied Hans, “there need be no question about it. It is only torturing the meaning of a word to suppose that Saint John ate the locust fruit, and not the insect. I am decidedly of opinion that the latter is meant in Scripture; and what makes me think so is, that these two kinds of food, ‘locusts and wild honey,’ are often coupled together, as forming at the present time the subsistence of many tribes who are denizens of the desert. Besides, we have good evidence that both were used as food by desert-dwelling people in the days of Scripture. It is, therefore, but natural to suppose that Saint John, when in the desert, was forced to partake of this food; just as many a traveller of modern times has eaten of it when crossing the deserts that surround us here in South Africa.

“I have read a great many books about locusts,” continued Hans; “and now that the Bible has been mentioned, I must say for my part, I know no account given of these insects so truthful and beautiful as that in the Bible itself. Shall I read it, papa?”

“By all means, my boy,” said the field-cornet, rather pleased at the request which his son had made, and at the tenor of the conversation.

Little Trüey ran into the inner room and brought out an immense volume bound in gemsbok skin, with a couple of strong brass clasps upon it to keep it closed. This was the family Bible; and here let me observe, that a similar book may be found in the house of nearly every boor, for these Dutch colonists are a Protestant and Bible-loving people—so much so, that they think nothing of going a hundred miles, four times in the year, to attend the nacht-maal, or sacramental supper! What do you think of that?

Hans opened the volume, and turned at once to the book of the prophet Joel. From the readiness with which he found the passage, it was evident he was well acquainted with the book he held in his hands.

He read as follows:—

“A day of darkness and of gloominess, a day of clouds and of thick darkness, as the morning spread upon the mountains; a great people and a strong: there hath not been ever the like, neither shall be any more after it, even to the years of many generations. A fire devoureth before them, and behind them a flame burneth: the land is as the garden of Eden before them, and behind them a desolate wilderness; yea, and nothing shall escape them. The appearance of them is as the appearance of horses; and as horsemen, so shall they run. Like the noise of chariots on the tops of mountains shall they leap, like the noise of a flame of fire that devoureth the stubble, as a strong people set in battle array.”

“The earth shall quake before them; the heavens shall tremble; the sun and the moon shall be dark, and the stars shall withdraw their shining.”

“How do the beasts groan! the herds of cattle are perplexed, because they have no pasture; yea, the flocks of sheep are made desolate.”

Even the rude Swartboy could perceive the poetic beauty of this description.

But Swartboy had much to say about the locusts, as well as the inspired Joel.

Thus spoke Swartboy:—

“Bushman no fear da springhaan. Bushman hab no garden—no maize—no buckwheat—no nothing for da springhaan to eat. Bushman eat locust himself—he grow fat on da locust. Ebery thing eat dem dar springhaan. Ebery thing grow fat in da locust season. Ho! den for dem springhaan!”

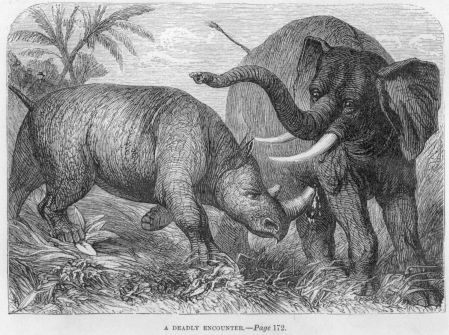

These remarks of Swartboy were true enough. The locusts are eaten by almost every species of animal known in South Africa. Not only do the carnivora greedily devour them, but also animals and birds of the game kind—such as antelopes, partridges, guinea-fowls, bustards, and, strange to say, the giant of all—the huge elephant—will travel for miles to overtake a migration of locusts! Domestic fowls, sheep, horses, and dogs, devour them with equal greediness. Still another strange fact—the locusts eat one another! If any one of them gets hurt, so as to impede his progress, the others immediately turn upon him and eat him up!

The Bushmen and other native races of Africa submit the locusts to a process of cookery before eating them; and during the whole evening Swartboy had been engaged in preparing the bagful which he had collected. He “cooked” them thus:—

He first boiled, or rather steamed them, for only a small quantity of water was put into the pot. This process lasted two hours. They were then taken out, and allowed to dry; and after that shaken about in a pan, until all the legs and wings were broken off from the bodies. A winnowing process—Swartboy’s thick lips acting as a fan—was next gone through; and the legs and wings were thus got rid of. The locusts were then ready for eating.

A little salt only was required to render them more palatable, when all present made trial of, and some of the children even liked them. By many, locusts prepared in this way are considered quite equal to shrimps!

Sometimes they are pounded when quite dry into a sort of meal, and with water added to them, are made into a kind of stir-about.

When well dried, they will keep for a long time; and they frequently form the only store of food, which the poorer natives have to depend upon for a whole season.

Among many tribes—particularly among those who are not agricultural—the coming of the locusts is a source of rejoicing. These people turn out with sacks, and often with pack-oxen to collect and bring them to their villages; and on such occasions vast heaps of them are accumulated and stored, in the same way as grain!

Conversing of these things the night passed on until it was time for going to bed. The field-cornet went out once again to observe the wind; and then the door of the little kraal was closed and the family retired to rest.

Chapter Five.

The Locust-Flight.

The field-cornet slept but little. Anxiety kept him awake. He turned and tossed, and thought of the locusts. He napped at intervals, and dreamt about locusts, and crickets, and grasshoppers, and all manner of great long-legged, goggle-eyed insects. He was glad when the first ray of light penetrated through the little window of his chamber.

He sprang to his feet; and, scarce staying to dress himself, rushed out into the open air. It was still dark, but he did not require to see the wind. He did not need to toss a feather or hold up his hat. The truth was too plain. A strong breeze was blowing—it was blowing from the west!

Half distracted, he ran farther out to assure himself. He ran until clear of the walls that enclosed the kraals and garden.

He halted and felt the air. Alas! his first impression was correct. The breeze blew directly from the west—directly from the locusts. He could perceive the effluvium borne from the hateful insects: there was no longer cause to doubt.

Groaning in spirit, Von Bloom returned to his house. He had no longer any hope of escaping the terrible visitation.

His first directions were to collect all the loose pieces of linen or clothing in the house, and pack them within the family chests. What! would the locusts be likely to eat them?

Indeed, yes—for these voracious creatures are not fastidious. No particular vegetable seems to be chosen by them. The leaves of the bitter tobacco plant appear to be as much to their liking as the sweet and succulent blades of maize! Pieces of linen, cotton, and even flannel, are devoured by them, as though they were the tender shoots of plants. Stones, iron, and hard wood, are about the only objects that escape their fierce masticators.

Von Bloom had heard this. Hans had read of it, and Swartboy confirmed it from his own experience.

Consequently, everything that was at all destructible was carefully stowed away; and then breakfast was cooked and eaten in silence.

There was a gloom over the faces of all, because he who was the head of all was silent and dejected. What a change within a few hours! But the evening before the field-cornet and his little family were in the full enjoyment of happiness.

There was still one hope, though a slight one. Might it yet rain? Or might the day turn out cold?

In either case Swartboy said the locusts could not take wing—for they cannot fly in cold or rainy weather. In the event of a cold or wet day they would have to remain as they were, and perhaps the wind might change round again before they resumed their flight. Oh, for a torrent of rain, or a cold cloudy day!

Vain wish! vain hope! In half-an-hour after the sun rose up in African splendour, and his hot rays, slanting down upon the sleeping host, warmed them into life and activity. They commenced to crawl, to hop about, and then, as if by one impulse, myriads rose into the air. The breeze impelled them in the direction in which it was blowing,—in the direction of the devoted maize-fields.

In less than five minutes, from the time they had taken wing, they were over the kraal, and dropping in tens of thousands upon the surrounding fields. Slow was their flight, and gentle their descent, and to the eyes of those beneath they presented the appearance of a shower of black snow, falling in large feathery flakes. In a few moments the ground was completely covered, until every stalk of maize, every plant and bush, carried its hundreds. On the outer plains too, as far as eye could see, the pasture was strewed thickly; and as the great flight had now passed to the eastward of the house, the sun’s disk was again hidden by them as if by an eclipse!

They seemed to move in a kind of echellon, the bands in the rear constantly flying to the front, and then halting to feed, until in turn these were headed by others that had advanced over them in a similar manner.

The noise produced by their wings was not the least curious phenomenon; and resembled a steady breeze playing among the leaves of the forest, or the sound of a water-wheel.

For two hours this passage continued. During most of that time, Von Bloom and his people had remained within the house, with closed doors and windows. This they did to avoid the unpleasant shower, as the creatures impelled by the breeze, often strike the cheek so forcibly as to cause a feeling of pain. Moreover, they did not like treading upon the unwelcome intruders, and crushing them under their feet, which they must have done, had they moved about outside where the ground was thickly covered.

Many of the insects even crawled inside, through the chinks of the door and windows, and greedily devoured any vegetable substance which happened to be lying about the floor.

At the end of two hours Von Bloom looked forth. The thickest of the flight had passed. The sun was again shining; but upon what was he shining? No longer upon green fields and a flowery garden. No. Around the house, on every side, north, south, east, and west, the eye rested only on black desolation. Not a blade of grass, not a leaf could be seen—even the very bark was stripped from the trees, that now stood as if withered by the hand of God! Had fire swept the surface, it could not have left it more naked and desolate. There was no garden, there were no fields of maize or buckwheat, there was no longer a farm—the kraal stood in the midst of a desert!

Words cannot depict the emotions of the field-cornet at that moment. The pen cannot describe his painful feelings.

Such a change in two hours! He could scarce credit his senses—he could scarce believe in its reality. He knew that the locusts would eat up his maize, and his wheat, and the vegetables of his garden; but his fancy had fallen far short of the extreme desolation that had actually been produced. The whole landscape was metamorphosed—grass was out of the question—trees, whose delicate foliage had played in the soft breeze but two short hours before, now stood leafless, scathed by worse than winter. The very ground seemed altered in shape! He would not have known it as his own farm. Most certainly had the owner been absent during the period of the locust-flight, and approached without any information of what had been passing, he would not have recognised the place of his own habitation!

With the phlegm peculiar to his race, the field-cornet sat down, and remained for a long time without speech or movement.

His children gathered near, and looked on—their young hearts painfully throbbing. They could not fully appreciate the difficult circumstances in which this occurrence had placed them; nor did their father himself at first. He thought only of the loss he had sustained, in the destruction of his fine crops; and this of itself, when we consider his isolated situation, and the hopelessness of restoring them, was enough to cause him very great chagrin.

“Gone! all gone!” he exclaimed, in a sorrowing voice. “Oh! Fortune—Fortune—again art thou cruel!”

“Papa! do not grieve,” said a soft voice; “we are all alive yet, we are here by your side;” and with the words a little white hand was laid upon his shoulder. It was the hand of the beautiful Trüey.

It seemed as if an angel had smiled upon him. He lifted the child in his arms, and in a paroxysm of fondness pressed her to his heart. That heart felt relieved.

“Bring me the Book,” said he, addressing one of the boys.

The Bible was brought—its massive covers were opened—a verse was chosen—and the song of praise rose up in the midst of the desert.

The Book was closed; and for some minutes all knelt in prayer.

When Von Bloom again stood upon his feet, and looked around him, the desert seemed once more to “rejoice and blossom as the rose.”

Upon the human heart such is the magic influence of resignation and humility.

Chapter Six.

“Inspann and Trek!”

With all his confidence in the protection of a Supreme Being, Von Bloom knew that he was not to leave everything to the Divine hand. That was not the religion he had been taught; and he at once set about taking measures to extricate himself from the unpleasant position in which he was placed.

Unpleasant position! Ha! It was more than unpleasant, as the field-cornet began to perceive. It was a position of peril!

The more Von Bloom reflected, the more was he convinced of this. There they were, in the middle of a black naked plain, that without a green spot extended beyond the limits of vision. How much farther he could not guess; but he knew that the devastations of the migratory locust sometimes cover an area of thousands of miles! It was certain that the one that had just swept past was on a very extensive scale.

It was evident he could no longer remain by his kraal. His horses, and cattle, and sheep, could not live without food; and should these perish, upon what were he and his family to subsist? He must leave the kraal. He must go in search of pasture, without loss of time,—at once. Already the animals, shut up beyond their usual hour, were uttering their varied cries, impatient to be let out. They would soon hunger; and it was hard to say when food could be procured for them.

There was no time to be lost. Every hour was of great importance,—even minutes must not be wasted in dubious hesitation.

The field-cornet spent but a few minutes in consideration. Whether should he mount one of his best horses, and ride off alone in search of pasture? or whether would it not be better to “inspann” his wagon, and take everything along with him at once?

He soon decided in favour of the latter course. In any case he would have been compelled to move from his present location,—to leave the kraal altogether.

He might as well take everything at once. Should he go out alone, it might cost him a long time to find grass and water—for both would be necessary—and, meantime, his stock would be suffering.

These and other considerations decided him at once to “inspann” and “trek” away, with his wagon, his horses, his cattle, his sheep, his “household gods,” and his whole family circle.

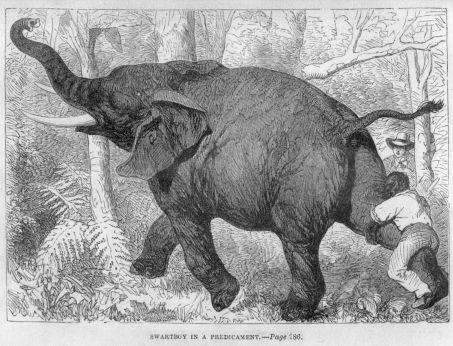

“Inspann and trek!” was the command: and Swartboy, who was proud of the reputation he had earned as a wagon-driver, was now seen waving his bamboo whip like a great fishing-rod.

“Inspann and trek!” echoed Swartboy, tying upon his twenty-feet lash a new cracker, which he had twisted out of the skin of the hartebeest antelope.

“Inspann and trek!” he repeated, making his vast whip crack like a pistol; “yes, baas, I’ll inspann;” and, having satisfied himself that his “voorslag” was properly adjusted, Swartboy rested the bamboo handle against the side of the house, and proceeded to the kraal to collect the yoke-oxen.

A large wagon, of a sort that is the pride and property of every Cape farmer, stood to one side of the house. It was a vehicle of the first class,—a regular “cap-tent” wagon,—that had been made for the field-cornet in his better days, and in which he had been used to drive his wife and children to the “nacht-maal” and upon vrolykheids (parties of pleasure.) In those days a team of eight fine horses used to draw it along at a rattling rate. Alas! oxen had now to take their place; for Von Bloom had but five horses in his whole stud, and these were required for the saddle.

But the wagon was almost as good as ever it had been,—almost as good as when it used to be the envy of the field-cornet’s neighbours, the boors of Graaf Reinet. Nothing was broken. Everything was in its place,—“voor-kist,” and “achter-kist,” and side-chests. There was the snow-white cap, with its “fore-clap” and “after-clap,” and its inside pockets, all complete; and the wheels neatly carved, and the well planed boxing and “disselboom” and the strong “trektow” of buffalo-hide. Nothing was wanting that ought to be found about a wagon. It was, in fact, the best part of the field-cornet’s property that remained to him,—for it was equal in value to all the oxen, cattle, and sheep, upon his establishment.

While Swartboy, assisted by Hendrik, was catching up the twelve yoke-oxen, and attaching them to the disselboom and trektow of the wagon, the “baas” himself, aided by Hans, Totty, and also by Trüey and little Jan, was loading up the furniture and implements. This was not a difficult task. The Penates of the little kraal were not numerous, and were all soon packed either inside or around the roomy vehicle.

In about an hour’s time the wagon was loaded up, the oxen were inspanned, the horses saddled, and everything was ready for “trekking.”

And now arose the question, whither?

Up to this time Von Bloom had only thought of getting away from the spot—of escaping beyond the naked waste that surrounded him.

It now became necessary to determine the direction in which they were to travel—a most important consideration.

Important, indeed, as a little reflection showed. They might go in the direction in which the locusts had gone, or that in which they had come? On either route they might travel for scores of miles without meeting with a mouthful of grass for the hungry animals; and in such a case these would break down and perish.

Or the travellers might move in some other direction, and find grass, but not water. Without water, not only would they have to fear for the cattle, but for themselves—for their own lives. How important then it was, which way they turned their faces!

At first the field-cornet bethought him of heading towards the settlements. The nearest water in that direction was almost fifty miles off. It lay to the eastward of the kraal. The locusts had just gone that way. They would by this time have laid waste the whole country—perhaps to the water or beyond it!

It would be a great risk going in that direction.

Northward lay the Kalihari desert. It would be hopeless to steer north. Von Bloom knew of no oasis in the desert. Besides the locusts had come from the north. They were drifting southward when first seen; and from the time they had been observed passing in this last direction, they had no doubt ere this wasted the plains far to the south.

The thoughts of the field-cornet were now turned to the west. It is true the swarm had last approached from the west; but Von Bloom fancied that they had first come down from the north, and that the sudden veering round of the wind had caused them to change direction. He thought that by trekking westward he would soon get beyond the ground they had laid bare.

He knew something of the plains to the west—not much indeed, but he knew that at about forty miles distance there was a spring with good pasturage around it, upon whose water he could depend. He had once visited it, while on a search for some of his cattle, that had wandered thus far. Indeed, it then appeared to him a better situation for cattle than the one he held, and he had often thought of moving to it. Its great distance from any civilised settlement was the reason why he had not done so. Although he was already far beyond the frontier, he still kept up a sort of communication with the settlements, whereas at the more distant point such a communication would be extremely difficult.

Now that other considerations weighed with him, his thoughts once more returned to this spring; and after spending a few minutes more in earnest deliberation, he decided upon “trekking” westward.

Swartboy was ordered to head round, and strike to the west. The Bushman promptly leaped to his seat upon the voor-kist, cracked his mighty whip, straightened out his long team, and moved off over the plain.

Hans and Hendrik were already in their saddles; and having cleared the kraals of all their live-stock, with the assistance of the dogs, drove the lowing and bleating animals before them.

Trüey and little Jan sat beside Swartboy on the fore-chest of the wagon; and the round full eyes of the pretty springbok could be seen peeping curiously out from under the cap-tent.

Casting a last look upon his desolate kraal, the field-cornet turned his horse’s head, and rode after the wagon.

Chapter Seven.

“Water! Water!”

On moved the little caravan, but not in silence. Swartboy’s voice and whip made an almost continual noise. The latter could be plainly heard more than a mile over the plain, like repeated discharges of a musket. Hendrik, too, did a good deal in the way of shouting; and even the usually quiet Hans was under the necessity of using his voice to urge the flock forward in the right direction.

Occasionally both the boys were called upon to give Swartboy a help with the leading oxen when these became obstinate or restive, and would turn out of the track. At such times either Hans or Hendrik would gallop up, set the heads of the animals right again, and ply the “jamboks” upon their sides.

This “jambok” is a severe chastener to an obstinate ox. It is an elastic whip made of rhinoceros or hippopotamus skin,—hippopotamus is the best,—near six feet long, and tapering regularly from butt to tip.

Whenever the led oxen misbehaved, and Swartboy could not reach them with his long “voorslag,” Hendrik was ever ready to tickle them with his tough jambok; and, by this means, frighten them into good behaviour. Indeed, one of the boys was obliged to be at their head nearly all the time.

A “leader” is used to accompany most teams of oxen in South Africa. But those of the field-cornet had been accustomed to draw the wagon without one, ever since the Hottentot servants fan away; and Swartboy had driven many miles with no other help than his long whip. But the strange look of everything, since the locusts passed, had made the oxen shy and wild; besides the insects had obliterated every track or path which oxen would have followed. The whole surface was alike,—there was neither trace nor mark. Even Von Bloom himself could with difficulty recognise the features of the country, and had to guide himself by the sun in the sky.

Hendrik stayed mostly by the head of the leading oxen. Hans had no difficulty in driving the flock when once fairly started. A sense of fear kept all together, and as there was no herbage upon any side to tempt them to stray, they moved regularly on.

Von Bloom rode in front to guide the caravan. Neither he nor any of them had made any change in their costume, but travelled in their everyday dress. The field-cornet himself was habited after the manner of most boors,—in wide leathern trousers, termed in that country “crackers;” a large roomy jacket of green cloth, with ample outside pockets; a fawn-skin waistcoat; a huge white felt hat, with the broadest of brims; and upon his feet a pair of brogans of African unstained leather, known among the boors as “feldt-schoenen” (country shoes). Over his saddle lay a “kaross,” or robe of leopard-skins, and upon his shoulder he carried his “roer”—a large smoothbore gun, about six feet in length, with an old-fashioned flint-lock,—quite a load of itself. This is the gun in which the boor puts all his trust; and although an American backwoodsman would at first sight be disposed to laugh at such a weapon, a little knowledge of the boor’s country would change his opinion of the “roer.” His own weapon—the small-bore rifle, with a bullet less than a pea—would be almost useless among the large game that inhabits the country of the boor. Upon the “karoos” of Africa there are crack shots and sterling hunters, as well as in the backwoods or on the prairies of America.

Curving round under the field-cornet’s left arm, and resting against his side, was an immense powder-horn—of such size as could only be produced upon the head of an African ox. It was from the country of the Bechuanas, though nearly all Cape oxen grow horns of vast dimensions. Of course it was used to carry the field-cornet’s powder, and, if full, it must have contained half-a-dozen pounds at least! A leopard-skin pouch hanging under his right arm, a hunting-knife stuck in his waist-belt, and a large meerschaum pipe through the band of his hat, completed the equipments of the trek-boor, Von Bloom.

Hans and Hendrik were very similarly attired, armed, and equipped. Of course their trousers were of dressed sheep-skin, wide—like the trousers of all young boors—and they also wore jackets and “feldt-schoenen,” and broad-brimmed white hats. Hans carried a light fowling-piece, while Hendrik’s gun was a stout rifle of the kind known as a “yäger”—an excellent gun for large game. In this piece Hendrik had great pride, and had learnt to drive a nail with it at nearly a hundred paces. Hendrik was par excellence the marksman of the party. Each of the boys also carried a large crescent-shaped powder-horn, with a pouch for bullets; and over the saddle of each was strapped the robe or kaross, differing only from their father’s in that his was of the rarer leopard-skin, while theirs were a commoner sort, one of antelope, and the other of jackal-skin. Little Jan also wore wide trousers, jacket, “feldt-schoenen,” and broad-brimmed beaver,—in fact, Jan, although scarce a yard high, was, in point of costume, a type of his father,—a diminutive type of the boor. Trüey was habited in a skirt of blue woollen stuff, with a neat bodice elaborately stitched and embroidered after the Dutch fashion, and over her fair locks she wore a light sun-hat of straw with a ribbon and strings. Totty was very plainly attired in strong homespun, without any head-dress. As for Swartboy, a pair of old leathern “crackers” and a striped shirt were all the clothing he carried, beside his sheep-skin kaross. Such were the costumes of our travellers.

For full twenty miles the plain was wasted bare. Not a bite could the beasts obtain, and water there was none. The sun during the day shone brightly,—too brightly, for his beams were as hot as within the tropics. The travellers could scarce have borne them had it not been that a stiff breeze was blowing all day long. But this unfortunately blew directly in their faces, and the dry karoos are never without dust. The constant hopping of the locusts with their millions of tiny feet had loosened the crust of earth; and now the dust rose freely upon the wind. Clouds of it enveloped the little caravan, and rendered their forward movement both difficult and disagreeable. Long before night their clothes were covered, their mouths filled, and their eyes sore.

But all that was nothing. Long before night a far greater grievance was felt,—the want of water.

In their hurry to escape from the desolate scene at the kraal, Von Bloom had not thought of bringing a supply in the wagon—a sad oversight, in a country like South Africa, where springs are so rare, and running streams so uncertain. A sad oversight indeed, as they now learnt—for long before night they were all crying out for water—all were equally suffering from the pangs of thirst.

Von Bloom thirsted, but he did not think of himself, except that he suffered from self-accusation. He blamed himself for neglecting to bring a needful supply of water. He was the cause of the sufferings of all the rest. He felt sad and humbled on account of his thoughtless negligence.

He could promise them no relief—at least none until they should reach the spring. He knew of no water nearer.

It would be impossible to reach the spring that night. It was late when they started. Oxen travel slowly. Half the distance would be as much as they could make by sundown.

To reach the water they would have to travel all night; but they could not do that for many reasons. The oxen would require to rest—the more so that they were hungered; and now Von Bloom thought, when too late, of another neglect he had committed—that was, in not collecting, during the flight of the locusts, a sufficient quantity of them to have given his cattle a feed.

This plan is often adopted under similar circumstances; but the field-cornet had not thought of it: and as but few locusts fell in the kraals where the animals had been confined, they had therefore been without food since the previous day. The oxen in particular showed symptoms of weakness, and drew the wagon sluggishly; so that Swartboy’s voice and long whip were kept in constant action.

But there were other reasons why they would have to halt when night came on. The field-cornet was not so sure of the direction. He would not be able to follow it by night, as there was not the semblance of a track to guide him. Besides it would be dangerous to travel by night, for then the nocturnal robber of Africa—the fierce lion—is abroad.

They would be under the necessity, therefore, of halting for the night, water or no water.

It wanted yet half-an-hour of sundown when Von Bloom had arrived at this decision. He only kept on a little farther in hopes of reaching a spot where there was grass. They were now more than twenty miles from their starting-point, and still the black “spoor” of the locusts covered the plain. Still no grass to be seen, still the bushes bare of their leaves, and barked!

The field-cornet began to think that he was trekking right in the way the locusts had come. Westward he was heading for certain; he knew that. But he was not yet certain that the flight had not advanced from the west instead of the north. If so, they might go for days before coming upon a patch of grass!

These thoughts troubled him, and with anxious eyes he swept the plain in front, as well as to the right and left.

A shout from the keen-eyed Bushman produced a joyful effect. He saw grass in front. He saw some bushes with leaves! They were still a mile off, but the oxen, as if the announcement had been understood by them, moved more briskly forward.

Another mile passed over, and they came upon grass, sure enough. It was a very scanty pasture, though—a few scattered blades growing ever the reddish surface, but in no place a mouthful for an ox. There was just enough to tantalise the poor brutes without filling their stomachs. It assured Von Bloom, however, that they had now got beyond the track of the locusts; and he kept on a little farther in hopes that the pasture might get better.

It did not, however. The country through which they advanced was a wild, sterile plain—almost as destitute of vegetation as that over which they had hitherto been travelling. It no longer owed its nakedness to the locusts, but to the absence of water.

They had no more time to search for pasture. The sun was already below the horizon when they halted to “outspann.”

A “kraal” should have been built for the cattle, and another for the sheep and goats. There were bushes enough to have constructed them, but who of that tired party had the heart to cut them down and drag them to the spot?

It was labour enough—the slaughtering a sheep for supper, and collecting sufficient wood to cook it. No kraal was made. The horses were tied around the wagon. The oxen, cattle, and sheep and goats, were left free to go where they pleased. As there was no pasture near to tempt them, it was hoped that, after the fatigue of their long journey, they would not stray far from the camp-fire, which was kept burning throughout the night.

Chapter Eight.

The fate of the Hero.

But they did stray.

When day broke, and the travellers looked around them, not a head of the oxen or cattle was to be seen. Yes, there was one, and one only—the milch-cow. Totty, after milking her on the previous night, had left her tied to a bush where she still remained. All the rest were gone, and the sheep and goats as well.

Whither had they strayed?

The horses were mounted, and search was made. The sheep and goats were found among some bushes not far off; but it soon appeared that the other animals had gone clean away.

Their spoor was traced for a mile or two. It led back on the very track they had come; and no doubt any longer existed that they had returned to the kraal.

To overtake them before reaching that point, would be difficult, if at all possible. Their tracks showed that they had gone off early in the night, and had travelled at a rapid rate—so that by this time they had most likely arrived at their old home.

This was a sad discovery. To have followed them on the thirsting and hungry horses would have been a useless work; yet without the yoke-oxen how was the wagon to be taken forward to the spring?

It appeared to be a sad dilemma they were in; but after a short consultation the thoughtful Hans suggested a solution of it.

“Can we not attach the horses to the wagon?” inquired he. “The five could surely draw it on to the spring?”

“What! and leave the cattle behind?” said Hendrik. “If we do not go after them, they will be all lost, and then—”

“We could go for them afterwards,” replied Hans; “but is it not better first to push forward to the spring; and, after resting the horses a while, return then for the oxen? They will have reached the kraal by this time. There they will be sure of water anyhow, and that will keep them alive till we get there.”

The course suggested by Hans seemed feasible enough. At all events, it was the best plan they could pursue; so they at once set about putting it in execution. The horses were attached to the wagon in the best way they could think of. Fortunately some old horse-harness formed part of the contents of the vehicle, and these were brought out and fitted on, as well as could be done.

Two horses were made fast to the disselboom as “wheelers;” two others to the trektow cut to the proper length; and the fifth horse was placed in front as a leader.

When all was ready, Swartboy again mounted the voor-kist, gathered up his reins, cracked his whip, and set his team in motion. To the delight of every one, the huge heavy-laden wagon moved off as freely as if a full team had been inspanned.

Von Bloom, Hendrik, and Hans, cheered as it passed them; and setting the milch-cow and the flock of sheep and goats in motion, moved briskly after. Little Jan and Trüey still rode in the wagon; but the others now travelled afoot, partly because they had the flock to drive, and partly that they might not increase the load upon the horses.

They all suffered greatly from thirst, but they would have suffered still more had it not been for that valuable creature that trotted along behind the wagon—the cow—“old Graaf,” as she was called. She had yielded several pints of milk, both the night before and that morning; and this well-timed supply had given considerable relief to the travellers.

The horses behaved beautifully. Notwithstanding that their harness was both incomplete and ill fitted, they pulled the wagon along after them as if not a strap or buckle had been wanting. They appeared to know that their kind master was in a dilemma, and were determined to draw him out of it. Perhaps, too, they smelt the spring-water before them. At all events, before they had been many hours in harness, they were drawing the wagon through a pretty little valley covered with green, meadow-looking sward; and in five minutes more were standing halted near a cool crystal spring.

In a short time all had drunk heartily, and were refreshed. The horses were turned out upon the grass, and the other animals browsed over the meadow. A good fire was made near the spring, and a quarter of mutton cooked—upon which the travellers dined—and then all sat waiting for the horses to fill themselves.

The field-cornet, seated upon one of the wagon-chests, smoked his great pipe. He could have been contented, but for one thing—the absence of his cattle.

He had arrived at a beautiful pasture-ground—a sort of oasis in the wild plains, where there were wood, water, and grass,—everything that the heart of a “vee-boor” could desire. It did not appear to be a large tract, but enough to have sustained many hundred head of cattle—enough for a very fine “stock farm.” It would have answered his purpose admirably; and had he succeeded in bringing on his oxen and cattle, he would at that moment have felt happy enough. But without them what availed the fine pasturage? What could he do there without them to stock it? They were his wealth—at least, he had hoped in time that their increase would become wealth. They were all of excellent breeds; and, with the exception of his twelve yoke-oxen, and one or two long-horned Bechuana bulls, all the others were fine young cows calculated soon to produce a large herd.

Of course his anxiety about these animals rendered it impossible for him to enjoy a moment’s peace of mind, until he should start back in search of them. He had only taken out his pipe to pass the time, while the horses were gathering a bite of grass. As soon as their strength should be recruited a little, it was his design to take three of the strongest of them, and with Hendrik and Swartboy, ride back to the old kraal.

As soon, therefore, as the horses were ready for the road again, they were caught and saddled up; and Von Bloom, Hendrik, and Swartboy, mounted and set out, while Hans remained in charge of the camp.

They rode at a brisk rate, determined to travel all night, and, if possible, reach the kraal before morning. At the last point on the route where there was grass, they off-saddled, and allowed their horses to rest and refresh themselves. They had brought with them some slices of the roast mutton, and this time they had not forgotten to fill their gourd-canteens with water—so that they should not again suffer from thirst. After an hour’s halt they continued their journey.

It was quite night when they arrived at the spot where the oxen had deserted them; but a clear moon was in the sky, and they were able to follow back the wheel-tracks of the wagon, that were quite conspicuous under the moonlight. Now and then to be satisfied, Von Bloom requested Swartboy to examine the spoor, and see whether the cattle had still kept the back-track. To answer this gave no great trouble to the Bushman. He would drop from his horse, and bending over the ground, would reply in an instant. In every case the answer was in the affirmative. The animals had certainly gone back to their old home.

Von Bloom believed they would be sure to find them there, but should they find them alive? That was the question that rendered him anxious.

The creatures could obtain water by the spring, but food—where? Not a bite would they find anywhere, and would not hunger have destroyed them all before this?

Day was breaking when they came in sight of the old homestead. It presented a very odd appearance. Not one of the three would have recognised it. After the invasion of the locusts it showed a very altered look, but now there was something else that added to the singularity of its appearance. A row of strange objects seemed to be placed upon the roof ridge, and along the walls of the kraals. What were these strange objects, for they certainly did not belong to the buildings? This question was put by Von Bloom, partly to himself, but loud enough for the others to hear him.

“Da vogels!” (the vultures), replied Swartboy.

Sure enough, it was a string of vultures that appeared along the walls.

The sight of these filthy birds was more than ominous. It filled Von Bloom with apprehension. What could they be doing there? There must be carrion near?

The party rode forward. The day was now up, and the vultures had grown busy. They flapped their shadowy wings, rose from the walls, and alighted at different points around the house.

“Surely there must be carrion,” muttered Von Bloom.

There was carrion, and plenty of it. As the horsemen drew near the vultures rose into the air, and a score of half-devoured carcasses could be seen upon the ground. The long curving horns that appeared beside each carcass, rendered it easy to tell to what sort of animals they belonged. In the torn and mutilated fragments, Von Bloom recognised the remains of his lost herd!

Not one was left alive. There could be seen the remains of all of them, both cows and oxen, lying near the enclosures and on the adjacent plain—each where it had fallen.

But how had they fallen? That was the mystery.

Surely they could not have perished of hunger, and so suddenly? They could not have died of thirst, for there was the spring bubbling up just beside where they lay? The vultures had not killed them! What then?

Von Bloom did not ask many questions. He was not left long in doubt. As he and his companions rode over the ground, the mystery was explained. The tracks of lions, hyenas, and jackals, made everything clear enough. A large troop of these animals had been upon the ground. The scarcity of game, caused by the migration of the locusts, had no doubt rendered them more than usually ravenous, and in consequence the cattle became their prey.

Where were they now? The morning light, and the sight of the house perhaps, had driven them off. But their spoor was quite fresh. They were near at hand, and would be certain to return again upon the following night.