« back

The Story of

RED FEATHER

A Tale of the American Frontier

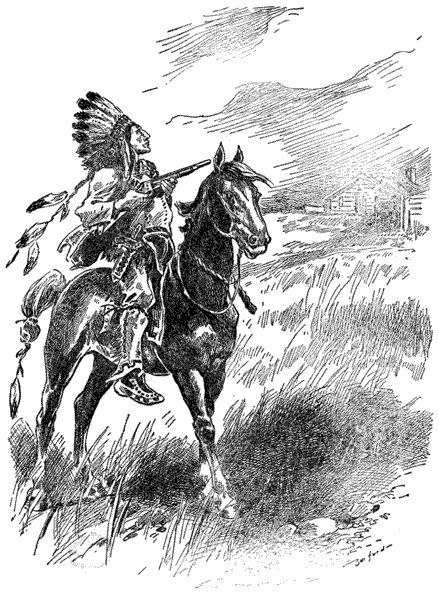

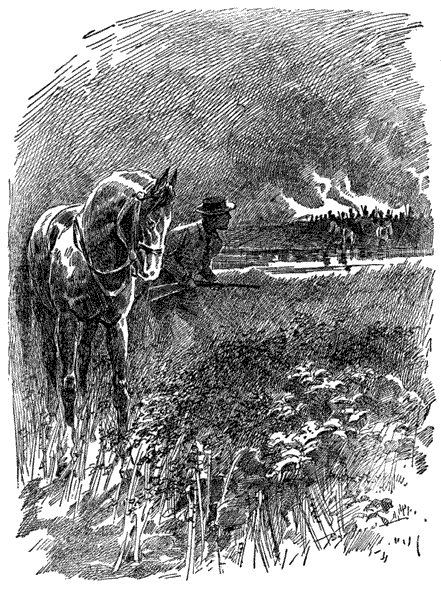

"He held his pony ready to send him flying over the prairie."—Page 131

"He held his pony ready to send him flying over the prairie."—Page 131

The Story of

RED FEATHER

A Tale of the American Frontier

By Edward S. Ellis

Illustrated

McLOUGHLIN BROTHERS, Inc.

MADE IN U. S. A.

McLOUGHLIN BROS. INC.

SPRINGFIELD MASS.

PUBLISHERS

1828

CHAPTER ONE

- Brother and Sister—The Signal 3

CHAPTER TWO

- An Important Letter—Shut in 14

CHAPTER THREE

- Caught Fast—A Friend in Need 25

CHAPTER FOUR

- The Consultation—On the Roof 36

CHAPTER FIVE

- A Strange Visit—Ominous Signs 47

CHAPTER SIX

- The Muddy Creek Band—The Torch 58

CHAPTER SEVEN

- "A Little Child Shall Lead Them"—Surrounded by Peril 69

CHAPTER EIGHT

- Tall Bear and his Warriors—A Surprising Discovery 80

CHAPTER NINE

- Nat Trumbull and his Men—Out in the Night 91

CHAPTER TEN

- An Old Friend—Separated 102

CHAPTER ELEVEN

- At the Lower Crossing—Tall Bear's Last Failure 114

CHAPTER TWELVE

- Conclusion 127

[3] THE STORY OF RED FEATHER

CHAPTER ONE

BROTHER AND SISTER—THE SIGNAL

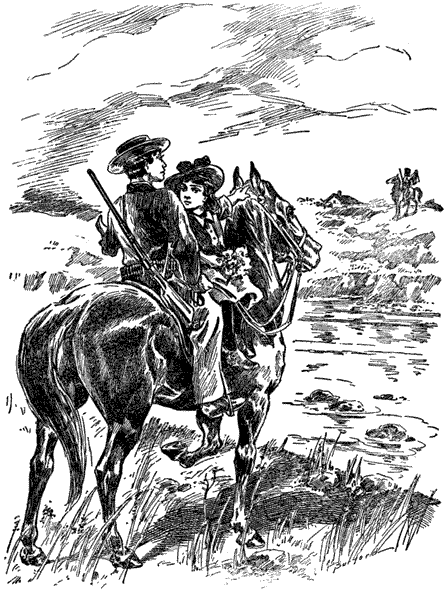

IT is within my memory that Melville Clarendon, a lad of sixteen years, was riding through Southern Minnesota, in company with his sister Dorothy, a sweet little miss not quite half his own age.

They were mounted on Saladin, a high-spirited, fleet, and good-tempered pony of coal-black color. Melville, who claimed the steed as his own special property, had given him his Arabian name because he fancied there were many points of resemblance between him and the winged coursers of the East, made famous as long ago as the time of the Crusades.

The lad sat his horse like a skilled equestrian, and indeed it would be hard to find his superior in that respect throughout that broad stretch of sparsely settled country. Those who live on the American frontier are trained from their earliest youth in the management of quadrupeds, and often display a proficiency that cannot fail to excite admiration.

Melville's fine breech-loading rifle was slung over his shoulder, and held in place by a strap that passed in front. It could be quickly drawn from its position whenever needed. It was not of the repeating pattern, but the youth was so handy with the weapon that he could [4]put the cartridges in place, aim, and fire not only with great accuracy, but with marked rapidity.

In addition, he carried a good revolver, though he did not expect to use either weapon on the short journey he was making. He followed, however, the law of the border, which teaches the pioneer never to venture beyond sight of his home unprepared for every emergency that is likely to arise.

It was quite early in the forenoon, Melville having made an early start from the border-town of Barwell, and he was well on his way to his home, which lay ten miles to the south. "Dot," as his little sister was called by her friends, had been on a week's visit to her uncle's at the settlement, the agreement all round being that she should stay there for a fortnight at least; but her parents and her big brother rebelled at the end of the week. They missed the prattle and sunshine which only Dot could bring into their home, and Melville's heart was delighted when his father told him to mount Saladin and bring her home.

And when, on the seventh day of her visit, Dot found her handsome brother had come after her, and was to take her home the following morning, she leaped into his arms with a cry of happiness; for though her relatives had never suspected it, she was dreadfully home-sick and anxious to get back to her own people.

In riding northward to the settlement, young Clarendon followed the regular trail, over which he had passed scores of times. Not far from the house he crossed a broad stream at a point where the current (except when there was rain) was less than two feet deep. Its shallowness led to its use by all the settlers within a large radius to the southward, so that the faintly marked trails converged at this point some[5]thing like the spokes of a large wheel, and became one from that point northward to the settlement.

A mile to the east was another crossing which was formerly used. It was not only broader, but there were one or two deep holes into which a horse was likely to plunge unless much care was used. Several unpleasant accidents of this nature led to its practical abandonment.

The ten miles between the home of the Clarendons and the little town of Barwell consisted of prairie, stream, and woodland. A ride over the trail, therefore, during pleasant weather afforded a most pleasing variety of scenery, this being especially the case in spring and summer. The eastern trail was more marked in this respect and it did not unite with the other until within about two miles of the settlement. Southward from the point of union the divergence was such that parties separating were quickly lost to view of each other, remaining thus until the stream of which I have spoken was crossed. There the country became so open that on a clear day the vision covered all the space between.

I have been thus particular in explaining the "lay of the land," as it is called, because it is necessary in order to understand the incidents that follow.

Melville laughed at the prattle of Dot, who sat in front of him, one of his arms encircling her chubby form, while Saladin was allowed to walk and occasionally gallop, as the mood prompted him.

There was no end of her chatter; and he asked her questions about her week's experience at Uncle Jack's, and told her in turn how much he and her father and mother had missed her, and what jolly times they would have when she got back.

Melville hesitated for a minute on reaching the diverging point [6]of the paths. He was anxious to get home; but his wish to give his loved sister all the enjoyment possible in the ride led him to take the abandoned trail, and it proved a most unfortunate thing that he did so.

Just here I must tell you that Melville and Dot Clarendon were dressed very much as boys and girls of their age are dressed to-day in the more settled parts of my native country. Remember that the incidents I have set out to tell you took place only a very few years ago.

Instead of the coon-skin cap, buckskin suit, leggings and moccasins, of the early frontier, Melville wore a straw hat, a thick flannel shirt, and, since the weather was quite warm, he was without coat or vest. His trousers, of the ordinary pattern, were clasped at the waist by his cartridge belt, and his shapely feet were encased in strong well-made shoes. His revolver was thrust in his hip-pocket, and the broad collar of his shirt was clasped at the neck by a twisted silk handkerchief.

As for Dot, her clustering curls rippled from under a jaunty straw hat, and fluttered about her pretty shoulders, while the rest of her visible attire consisted of a simple dress, shoes, and stockings. The extra clothing taken with her on her visit was tied in a neat small bundle, fastened to the saddle behind Melville. Should they encounter any sudden change in the weather, they were within easy reach, while the lad looked upon himself as strong enough to make useless any such care for him.

Once or twice Melville stopped Saladin and let Dot down to the ground, that she might gather some of the bright flowers growing by the wayside; and at a spring of bubbling icy-cold water both halted and quaffed their fill, after which Saladin was allowed to push his nose into the clear fluid and do the same.

[7]Once more they mounted, and without any occurrence worth the telling, reached the bank of the stream at the Upper Crossing. He halted a minute or two to look around before entering the water, for, as you will bear in mind, he had now reached a spot which gave him a more extended view than any yet passed.

Their own home was in plain sight, and naturally the eyes of the brother and sister were first turned in that direction. It appeared just as they expected. Moderate in size, built of logs somewhat after the fashion on the frontier at an earlier date, with outbuildings and abundant signs of thrift, it was an excellent type of the home of the sturdy American settler of the present.

"Oh, Mel!" suddenly exclaimed Dot, calling her brother by the name she always used, "who is that on horseback?"

Dot pointed to a slight eminence between their house and the stream; and, shifting his glance, Melville saw an Indian horseman standing as motionless as if he and his animal were carved in stone. He seemed to have reined up on the crest of the elevation, and, coming to a halt, was doing the same as the brother and sister—surveying his surroundings.

His position was midway between Melville and his house, and his horse faced the brother and sister. The distance was too great to distinguish the features of the red man clearly, but the two believed he was looking at them.

Now, there was nothing to cause special alarm in this sight, for it was a common thing to meet Indians in that part of the country, where indeed many of them may be seen to-day; but the lad suddenly remembered that when looking in the direction of his home he had failed to see any signs of life, and he was at once filled with a mis[8]giving which caused him to swallow a lump in his throat before answering the question—

"Who is it, Mel?"

"Some Indian; he is too far off for me to tell who he is, and likely enough we have never seen him before."

"What's he looking at us so sharply for?"

"I'm not sure that he is looking at us; his face seems to be turned this way, but he may have his eyes on something else."

"Watch him! See what he is doing!"

No need to tell the lad to watch, for his attention was fixed upon the warrior. Just as Dot spoke he made a signal which the intelligent youth could not comprehend. He flung one end of a blanket in the air slightly above and in front of him, and, holding the other part in his hand, waved it vigorously several times.

That it was intended for the eyes of the brother and sister seemed beyond all question; but, as I have said, they did not know what it meant, for it might have signified a number of things. It is a practice with many Indians to use such means as a taunt to their enemies, but they generally utter shouts and defiant cries, and nothing of the kind was now heard.

Besides this, it was not to be supposed that a Sioux warrior (that, no doubt, being the tribe of the red man before them) would indulge in any such action in the presence of a single white youth and small girl.

"I don't understand it," said Melville, "but I'll be as polite as he."

With which, he took off his hat and swung it above his head. Then, seeing that the Indian had ceased waving his blanket, he replaced his hat, still watching his movements.

[11]The next moment the Sioux wheeled his horse, and heading westward, galloped off with such speed that he almost instantly vanished.

The Indian had been gone less than a minute when Melville spoke to Saladin, and he stepped into the water.

The instant his hoof rested on dry land the youth struck him into a swift canter, which was not checked until he arrived at the house. While yet some distance, the lad's fears were deepened by what he saw, or rather by what he failed to see. Not a horse or cow was in sight; only the ducks and chickens were there, the former waddling to the water.

When Archie Clarendon made his home on that spot, a few years before, one of the questions he had to meet was as to the best way of guarding against attacks from Indians, for there were plenty of them in that part of the country. There are very few red men who will not steal; and they are so fond of "firewater," or intoxicating drink, that they are likely to commit worse crimes.

The pioneer, therefore, built his house much stronger than he would have done had he waited several years before putting it up.

It was made of logs, strongly put together, and the windows were so narrow that no person, unless very slim, could push his way through them. Of course the door was heavy, and it could be fastened in its place so firmly that it would have resisted the assault of a strong body of men.

By this time Melville, who had galloped up to the front and brought his horse to a halt, was almost sure that something dreadful had happened, and he hesitated a moment before dismounting or lowering Dot to the ground. She began twisting about in his grasp, saying plaintively—

[12]"Let me down, Mel; I want to see papa and mamma."

"I don't think they are there," he said, again swallowing a lump in his throat.

She turned her head around and looked wonderingly up in his face, not knowing what he meant. He could not explain, and he allowed her to drop lightly on her feet.

"Wait a minute," he called, "till I take a look inside."

In imagination he saw an awful sight. It was that of his beloved parents slain by the cruel red men—one of whom had waved his blanket tauntingly at him only a few minutes before.

He could not bear that Dot should look upon the scene that would haunt her, as it would haunt him, to her dying day. He meant to hold her back until he could take a look inside; but her nimble feet carried her ahead, and she was on the porch before he could check her.

Saladin was a horse that would stand without tying; and, paying no heed to him, the youth hurried after his sister, seizing her hand as it was raised to draw the string hanging outside the door.

"Dot," he said, "why do you not obey me? You must wait till I first go in."

It was not often her big brother spoke so sternly, and there came a tear into each of the bright eyes, as she stepped back and poutingly waited for him to do as he thought best.

Melville raised his hand to draw the latch, but his heart failed. Stepping to one side, he peered through the narrow window that helped to light up the lower floor.

The muslin curtain was partly drawn, but he was able to see most of the interior. Table, chairs, and furniture were all in place, but not a glimpse of a living person was visible.

The emotions of childhood are as changeable as the shadows of the flitting clouds.

Dot was pouting while Mel stood irresolute on the small porch, and was sure she would never, never speak to the mean fellow again; but the instant he peeped through the narrow window she forgot everything else, and darted forward to take her place at his side, and find out what it was that made him act so queerly.

Before she reached him she stopped short with the exclamation—

"Oh, Mel! here's a letter for you!"

[14]

CHAPTER TWO

AN IMPORTANT LETTER—SHUT IN

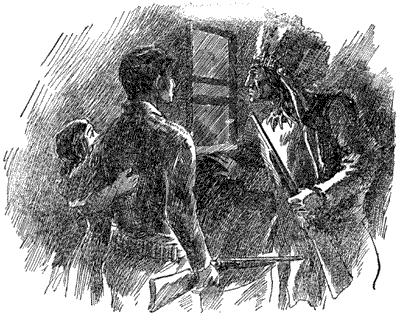

ASTONISHED by the cry, young Clarendon turned his head and looked at his sister, who landed at his side that moment like a fairy. She was holding a sheet of paper in her hand. It was folded in the form of an envelope, and pencilled on the outside in bold letters were the words—

"Melville Clarendon.

"In haste; read instantly."

He took the letter from his sister and trembled, as if from a chill, as he hurriedly unfolded the paper and read—

"My Dear Mel,—Leave at once! The Sioux have taken the war-path, and a party of their worst warriors from the Muddy Creek country have started out on a raid. They are sure to come this way, and I suppose the house will be burned, and everything on which they can lay hands destroyed. They are under the lead of the desperate Red Feather, and will spare nothing. A friendly Sioux stopped this morning before daylight and warned me. I gathered the animals together, and your mother and I set out for Barwell in all haste, driving the beasts before us.

"I feel certain of either finding you and Dot at my brother's in

the settlement or of meeting you on the way, for I suppose, of

course, you will follow the regular trail; but, at the moment of

starting, your mother suggests the possibility that you may take

the upper route. [15]To make sure, I write this letter. If the

Indians reach the building before you, they will leave such

traces of their presence that you will take the alarm. If you

arrive first and see this note, re-mount Saladin, turn

northward, and lose not a minute in galloping to the settlement.

None of them can overtake you. Avoid the upper trail, where it

is much easier for them to ambush you; keep as much on the open

prairie as possible; see that your weapons are loaded; make

Saladin do his best; and God be with you and Darling Dot.—

Your Father."

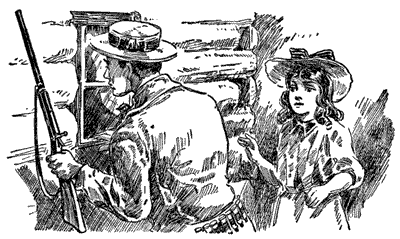

"He hurriedly unfolded the paper and read."

"He hurriedly unfolded the paper and read."

The youth read this important message aloud to Dot, who stood at his side, looking wistfully up in his face. She was too young to comprehend fully its meaning, but she knew that her parents had left for the settlement, and that her father had ordered Melville to follow at once with her.

"The bad Indians are coming," he added, "and if we stay here they will shoot us. I don't think," he said, glancing around, "that [16]they are anywhere near; but they are likely to come any minute, so we won't wait."

"Oh, Mel!" suddenly spoke up Dot, "you know I forgot to take Susie with me when I went away; can't I get her now?"

Susie was Dot's pet doll, and the fact that she left it behind when making her visit to Uncle Jack's had a great deal more to do with her home-sickness than her friends suspected. The thought of leaving it behind again almost broke her heart.

"I am sure mother took it with her when she went off this morning," replied Melville, feeling a little uneasy over the request.

"I'll soon find out," said she, stepping hastily towards the door.

He could not refuse her wish, for he understood the depth of the affection she felt for the doll, whose dress was somewhat torn, and whose face was not always as clean as her own. Besides, it could take only a minute or two to get the plaything, if it had been left in the house. Although his situation prevented his seeing anything in the rear of the building, he was sure the dreaded Indians were not yet in sight, and he desired to make a hasty survey of the interior of the house himself.

How familiar everything looked! There were the chairs placed against the wall, and the deal table in the middle of the room. Melville noticed that the pictures which had hung so long on the walls had been taken away. They were portraits of the members of the family, and the mother looked upon them as too precious to be allowed to run any risk of loss. A few other valuables, including the old Bible, had been removed; but the parents were too wise to increase their own danger by loading themselves with goods, however much they regretted leaving them behind.

[17]Although there was an old-fashioned fire-place, the Clarendons used a large stove standing near it. Curiosity led Melville to examine it, and he smiled to find it still warm. The ashes within, when stirred, showed some embers glowing beneath. There was something in the fact which made the youth feel as though the distance between him and his parents had become less than a short time before.

"Strange that I took the upper trail," he said to himself, resuming his standing position, "and thereby missed them. It's the first time I have been over that course for a long while, and it beats me that to-day when I shouldn't have done so I must do it; but fortunately no harm was done."

It struck him that Dot was taking an unusually long time in the search for her doll. Walking to the foot of the stairs, he called to her—

"It won't do to wait any longer, Dot; we must be off. If you can't find your doll, it's because mother took it with her."

"I've found it! I've found it!" she exclaimed, dancing with delight; "I had hid it in the bed, where mother didn't see it; bless your soul, Susie!"

And Melville laughed as he heard a number of vigorous smacks which told how much the child loved her pet.

"I suppose you are happy now," remarked Melville, taking her hand, while he held his gun in the other, as they walked towards the door.

"Indeed I am," she replied, with that emphatic shake of the head by which children of her years often give force to their words.

Melville placed his hand on the latch of the door, and, raising it, drew the structure inward. He had lowered his arm and once more [18]taken the hand of his sister, and was in the act of stepping outside, when the sharp report of a rifle broke the stillness, and he felt the whiz of the bullet, which grazed his face and buried itself in the wall behind him.

The lad was quick-witted enough to know on the instant what it meant; and, leaping back, he hastily closed the door, drew in the latch-string, and, leaning his rifle against the side of the room, slipped the bar in place.

He had hardly done so when there was a shock, as if some heavy body were flung violently against it. Such was the fact, a Sioux warrior having turned himself sideways at the moment of leaping, so that his shoulder struck it with a force sufficient to carry a door off its hinges.

"What's the matter?" asked the frightened Dot; "why do you fasten the door, Mel?"

"The bad Indians have come; they are trying to get into the house so as to hurt us."

"And do they want Susie?" she asked Melville, hugging her doll very closely to her breast.

"Yes, but we won't let them have her. Keep away from the window!" he added, catching her arm, and drawing her back from the dangerous position into which her curiosity was leading her. "Sit down there," he said, pointing to one of the chairs which was beyond reach of any bullet that could be fired through a window; "don't stir unless I tell you to, or the bad Indians will take you and dolly, and you will never see father or mother or me again."

This was terrible enough to scare the little one into the most implicit obedience of her brother. She meekly took her seat, with Susie [19]still clasped in her arms, willing to do anything to save the precious one from danger, and content to leave everything to her brother.

The youth had not time to explain matters more fully to his sister, nor would it have been wise to do so; she had been told enough already to distress and render her obedient to his wishes.

Following the startling shock against the door came a voice from the outside. The words were in broken English, and were uttered by the Sioux warrior that had made the vain effort to drive the structure inward.

"Open door—open door, brudder."

"I will not open the door," called back Melville.

"Open door—Injin won't hurt pale-face—come in—eat wid him."

"You cannot come in; we want no visitors. Go away, or I will shoot you!"

This was a brave threat, but it did not do all that the lad hoped. Whether the assailants knew how weak the force was within the house the youth could not say. He was not without belief that they might think there were several armed defenders who would make an attack or siege on the part of the Sioux too costly for them to continue it long.

The first purpose of Melville, therefore, was to learn how strong the force was that had made such a sudden attack. It was too perilous to attempt to look through one of the four narrow windows lighting the large room where he stood, and which covered the entire lower part of the building, and he decided, therefore, to got upstairs.

Before doing so, he made Dot repeat her promise to sit still where she was. She assured him that he need have no fear whatever, and he hurriedly made his way to the rooms above.

[20]Advancing to one of the windows at the front, he peered out with the utmost caution.

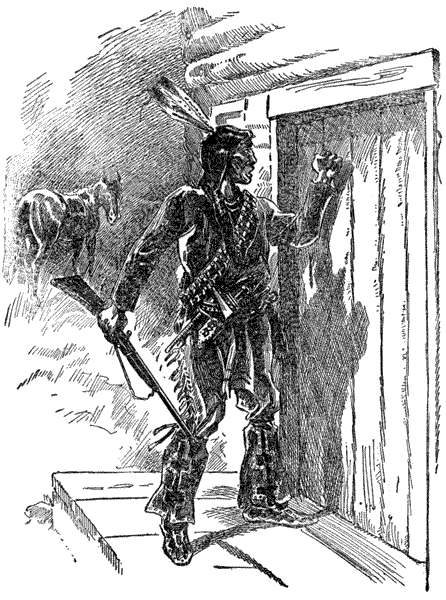

The first Indian whom he saw was the very one he dreaded above all others. He recognized him at the first glance by the cluster of eagle-feathers stuck in his crown. There were stained of a crimson red, several of the longer ones drooping behind, so as to mingle with his coarse black hair which streamed over his shoulders.

This was Red Feather, one of the most desperate Sioux known in the history of the border. Years before he was a chief noted for his daring and detestation of the white men. As the country became partly settled he acquired most of the vices and few of the virtues of the white race. He was fond of "firewater," was an inveterate thief, sullen and revengeful, quarrelsome at all times; and, when under the influence of drink, was feared almost as much by his own people as by the whites.

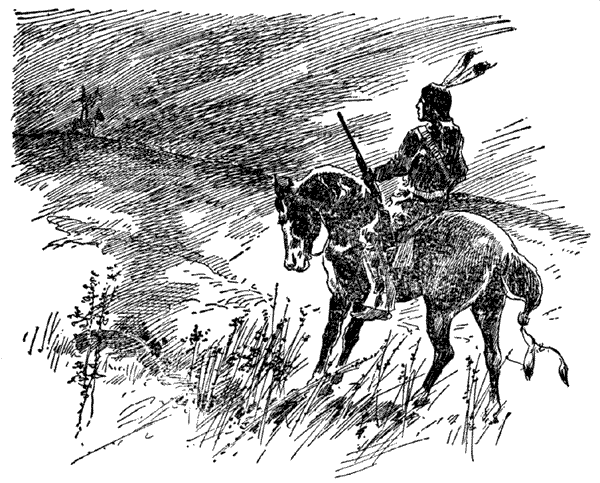

Red Feather was mounted on a fine-looking horse, which there is little doubt had been stolen from some of the settlers in that part of the country. He had brought him to a stand about a hundred yards from the building, he and the animal facing the house.

As the Sioux chieftain held this position the lad was struck by his resemblance to the horseman whom he and Dot noticed at the time they halted on the other bank of the stream.[21]

This discovery of young Clarendon suggested an explanation of the sight which so puzzled him and his sister. The chief had descried them at the same moment, if not before they saw him. Inasmuch as the occupants of the building were absent, he must have thought they had gone off together, and he could not have believed that, if such were the case, any members of the company would return—the [23]boy, therefore, had ridden part way back to learn what was to be fate of the cabin and property left behind. Red Feather had waved his blanket as a taunt, and then rode off for his warriors, encamped near by, with the purpose of directing them in an attack on the house.

It was a most unfortunate oversight that Melville did not make a survey of the surrounding country before entering his own home, for had he done so, he would have learned of his peril; but you will remember that his first purpose was not to enter his house, and in truth it was Susie, the little doll, that brought all the trouble.

The dismay caused by his unexpected imprisonment was not without something in the nature of relief.

In the first place, a careful survey of his surroundings showed there were only six Sioux warriors in the attacking party. All were mounted, as a matter of course, fully armed, and eager to massacre the settler and his family. You will say these were enough to frighten any lad, however brave; but you must remember that Melville held a strong position in the house.

Such a fine horse as Saladin could not fail to catch the eye of the dusky scamps, and at the moment Red Feather fired his well-nigh fatal shot at the youth three warriors were putting forth their utmost efforts to capture the prize.

But the wise Saladin showed no liking for the red men, and would not permit any of them to lay hands on him. It was an easy matter to do this, for among them all there was not one that could approach him in fleetness. He suffered them to come quite near, and then, flinging up his head with a defiant neigh, sped beyond their reach like an arrow darting from the bow.

Melville's eyes kindled.

[24]"I am proud of you, Saladin," he said, "and if I dared, I would give you a hurrah."

He watched the performance for several minutes, the rapid movement of the horses causing him to shift his position once or twice from one side of the house to the other. Finally, one of the Sioux saw how idle their pursuit was, and, angered at being baffled, deliberately raised his rifle and fired at Saladin.

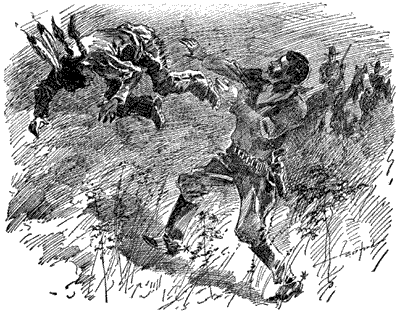

"Saladin showed no liking for the red men."

"Saladin showed no liking for the red men."

Whether he hit the horse or not Melville could not say, though the animal showed no signs of being hurt: but the lad was so indignant that he levelled his own weapon, and, pointing the muzzle out of the narrow window, muttered—

"If you want to try that kind of business, I'm willing, and I think I can make a better shot than you did."

[25]Before, however, he could be sure of his aim, he was startled by a cry from Dot—

"Come down here quick, Mel! A great big Indian is getting in the house by the window!"

CHAPTER THREE

CAUGHT FAST—A FRIEND IN NEED

MELVILLE Clarendon was so interested in the efforts of the three Sioux to capture his horse, that for a minute or two he forgot that Dot was below-stairs. Her cry, however, roused him to the situation and truth, and he flew down the steps.

In fact, the little girl had had a stirring time. While she was too young to realize the full danger of herself and brother, she knew there were bad Indians trying to get into the house, and the best thing for her to do was to obey every instruction Melville gave to her.

It will be recalled that Melville had a few words of conversation with one of the Sioux outside the door, who asked to be admitted. After the youth's refusal, there was silence for a minute or two, and, supposing the Indian was gone, the lad hurried to the upper story to gain a survey of his surroundings.

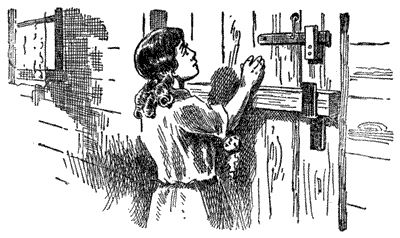

But the warrior had not left. After the departure of Melville he resumed his knocking on the door, but so gently that no one heard him except Dot. In her innocence she forgot the warnings given to her, and, sliding off her chair, stepped forward, and began shoving the end of the leathern string through, so that the Indian could raise [26]the latch. She had tried to raise it herself, but the pressure from the outside was so strong that the friction prevented.

"Pull the string, and the door will open."

"Pull the string, and the door will open."

"There!" said the little girl; "all you've got to do is to pull the string, and the door will open."

When the Indian saw the head of the string groping its way through the little hole in the door like a tiny serpent, he grasped the end, and gave it such a smart jerk that the latch flew up.

But, fortunately, it was necessary to do more than draw the latch to open the door. The massive bar was in place, and the Sioux, most likely with a suspicion of the truth, made no effort to force the structure.

But while he was thus employed Red Feather had slipped from the back of his pony and approached the house. He took the side opposite to that from which Melville was looking forth, so that the youth did not notice his action. He saw the idleness of trying to make his way through the door, and formed another plan.

With little effort he raised the sash in the narrow window on the [27]right. About half-way to the top was a wooden button to hold the lower sash in place when raised. The occupants of the house used no care in securing the windows, since, as I have explained, they were too narrow to allow any person, unless very thin of figure, to force his way through them.

Red Feather seemed to forget that he had tried to take the life of one of the white persons only a few minutes before; but, since no return shot had come from within the building, he must have concluded the defenders were panic-stricken, or else he showed a daring that amounted to recklessness; for, after raising the sash, he pushed the curtain aside, and began carefully shoving his head through the opening.

Now, the house being of logs, it was necessary for the chieftain to force his shoulders a slight distance to allow his head fairly to enter the room. This required great care and labor, and more risk on the part of the Sioux than he suspected—since he should have known that it is easier to advance under such circumstances than to retreat, and, inasmuch as it was so hard to push on, it was likely to be still harder to retreat.

Dot Clarendon, like her brother, was so interested in another direction that she failed for the time to note that which was of far more importance.

But the feeling that she and her brother were in a situation of great danger became so strong that she felt there was only One who could save them, and, just as she had been taught from earliest infancy, she now asked that One to take care of them.

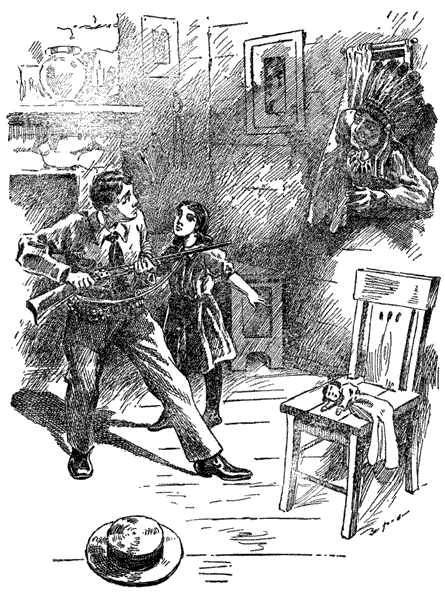

Sinking on her chubby knees, she folded her hands, shut her eyes and poured out the simple prayer of faith and love to Him whose ear [28]is never closed to the appeal of the most helpless. Her eyes were still closed, and her lips moving, when the noise made by Red Feather in forcing himself through the narrow opening caused her to stop suddenly and look around.

The sight which met her gaze was enough to startle the bravest man. The head and shoulders of a hideous Sioux warrior were within six feet of where she was kneeling. The Indian was still struggling but he could get no farther, and, as it was, he was wedged very closely.

It must have caused strange feelings in the heart of the wicked savage when he observed the tiny figure kneeling on the floor, with clasped hands, closed eyes, upturned face, and murmuring lips. It is hard to think there could be any one untouched by the sight, though Red Feather gave no sign of such emotion at the time.

The face of the Sioux was not painted, though it is the fashion of his people to do so when upon the war-trail. It could not have looked more frightful had it been daubed with streaks and spots, and Dot was terrified. Springing to her feet, she recoiled with a gasp, and stared at the dreadful countenance.

Red Feather beckoned as best he could for the little one to come nigh him.

It was at this juncture that Dot uttered the cry which brought Melville in such haste from the room above. He rushed down, loaded gun in hand, and it is stating the matter mildly to say that he effected a change in the situation. Startled by the sound of the steps on the stairs, Red Feather glanced up and saw the lad, his face white with anger, and a very dangerous-looking rifle in his hand.

"I'll teach you manners!" called out Melville, halting on reaching [29]the floor, and bringing his weapon to a level; "such a rogue as you ain't fit to live."

"Poured out the simple prayer of faith and love."

"Poured out the simple prayer of faith and love."

As you may suppose, Red Feather was satisfied that the best thing for him to do was to leave that place as quickly as he knew how. He began struggling fiercely to back out, and he must have been surprised when he found he was fast, and that the more he strove to free himself the more firmly he became wedged in.

Seeing his predicament, Melville advanced a couple of steps, holding his weapon so that its muzzle was within arm's length of the terrified visage of the chieftain.

"I've got you, Red Feather!" said the exultant youth; "and the best thing I can do is to shoot you."

[30]"Oh, Mel!" called Dot, running towards her brother, "don't hurt him, for that would be wicked."

I must do Melville Clarendon the justice to state that he had no intention of shooting the Sioux chieftain who was caught fast in such a curious way. Such an act would have been cruel, though many persons would say it was right, because Red Feather was trying to slay both Melville and his little sister.

But the youth could not help enjoying the strange fix in which the Indian was caught, and he meant to make the best use of it. It is not often that an American Indian loses his wits when in danger, but Red Feather, for a few minutes, was under the control of a feeling such as a soldier shows when stricken by panic.

Had he kept cool, and carefully turned and twisted about as required, while slowly drawing backward, he could have released himself from the snare without trouble; but it was his frantic effort which defeated his own purpose, and forced him to stop, panting and despairing, with his head still within the room, and at the mercy of the youth, who seemed to lower his gun only at the earnest pleading of his little sister.

It was no more than natural that the Sioux should have felt certain that his head and shoulders were beginning to swell, and that, even if the lad spared him, he would never be able to get himself out of the scrape, unless the side of the house should be first taken down.

It was a time to sue for mercy, and the desperate, ugly-tempered Red Feather was prompt to do so. Ceasing his efforts, and turning his face, all aglow with cold perspiration, towards the boy, who had just lowered the muzzle of his gun, he tried to smile, though the expression of his countenance was anything but smiling, and said—

[31]"Red Feather love white boy—love white girl!"

It is hard to restrain one's pity for another when in actual distress, and Melville's heart was touched the instant the words were uttered.

"Sit down in your chair," he said gently to Dot, "and don't disobey me again by leaving it until I tell you."

"But you won't hurt him, will you?" she pleaded, half obeying, and yet hesitating until she could receive his answer.

Not wishing Red Feather to know his decision, he stooped over and whispered in her ear—

"No, Dot, I will not hurt him; but don't say anything, for I don't want him to know it just yet."

It is more than likely that the distressed Sioux saw enough in the bright face to awaken hope, for he renewed his begging for mercy.

"Red Feather love white folks—he been bad Injin—he be good Injin now—'cause he love white folks."

"Red Feather," said he, lowering his voice so as not to reach the ears of the other Sioux, drawn to the spot by the strange occurrence; "you do not deserve mercy, for you came to kill me and all my folk. There! don't deny it, for you speak with a double tongue. But she has asked me to spare you, and perhaps I will. If I keep away all harm from you, what will you do for us?"

"Love white folks—Red Feather go away—won't hurt—bring game to his brother."

Having rested a few minutes, the Sioux began wriggling desperately again, hoping to free himself by sheer strength; but he could not budge his head and shoulders from their vice-like imprisonment, and something like despair must have settled over him when all doubt that he was swelling fast was removed.

[32]It was at the same instant that two of the warriors on the outside, seeing the hapless position of their chief, seized his feet, and began tugging with all their power.

They quickly let go, however; for the impatient sachem delivered such a vigorous kick that both went over backward, with their feet pointed towards the clouds.

"Red Feather," said Melville, standing close enough to the hapless prisoner to touch him with his hand, "if I help you out of that place and do not hurt you, will you and your warriors go away?"

The Sioux nodded so vigorously that he struck his chin against the wood hard enough to cause him some pain.

"Me go away—all Sioux go away—neber come here 'gin—don't hurt nuffin—hurry way."

"And you will not come back to harm us?"

"Neber come back—stay way—love white folks."

"I don't believe you will ever love them, and I don't ask you to do so; but you know that my father and mother and I have always treated your people kindly, and they have no reason to hurt us."

"Dat so—dat so—Red Feather love fader, love moder, love son, love pappoose of white folks."

"You see how easy it would be for me to shoot you where you are now without any risk to myself, but I shall not hurt you. I will help to get your head and shoulders loose; but I am afraid that when you mount your horse again and ride out on the prairie you will forget all you promised me."

"Neber, neber, neber!" replied the chieftain, with all the energy at his command.

"You will think that you know enough never to run your head [35]into that window again, and you will want to set fire to the house and tomahawk us."

The Sioux looked as if he was deeply pained at this distrust of his honorable intentions, and he seemed at a loss to know what to say to restore himself to the good graces of his youthful master.

"You are sure you won't forget your promise, Red Feather?"

"Red Feather Sioux chief—he neber tell lie—he speak wid single tongue—he love white folks."

"I counted five warriors with you; are they all you have?"

"Dey all—hab no more."

Melville believed the Indian spoke the truth.

"Where are the rest?"

"Go down oder side Muddy Riber—won't come here."

Melville was inclined to credit this statement also. If Red Feather spoke the truth, the rest of his band, numbering fully a score, were twenty miles distant, and were not likely to appear in that part of the country. Such raids as that on which they were engaged must of necessity be pushed hard and fast. Even if the settlers do not instantly rally, the American cavalry are quite sure to follow them, and the Indians have no time to loiter. The rest of the band, if a score of miles away, were likely to have their hands full without riding thus far out of their course.

"Well," said Melville, after a moment's thought, as if still in doubt as to what he ought to do, "I shall not hurt you—more than that, I will help you to free yourself."

He leaned his gun against the table near him, and stepped forward and placed his hands on the head and shoulders of the suffering prisoner.

[36]"Oogh!" grunted Red Feather; "grow bigger—swell up fast—bimeby Red Feather get so big, he die."

"I don't think it is as bad as that," remarked Melville, unable to repress a smile, "but it will take some work to get you loose."

CHAPTER FOUR

THE CONSULTATION—ON THE ROOF

MELVILLE now examined the fix of the chieftain more closely. His struggles had hurt the skin about his neck and shoulders, and there could be no doubt he was suffering considerably.

Clasping the dusky head with his hands, the youth turned it gently, so that it offered the least possible resistance. Then he asked him to move his shoulder slightly to the left, and, while Melville pushed carefully but strongly, told him to exert himself, not hastily but slowly, and with all the power at his command.

Resting a minute or two, the attempt was renewed and this time Red Feather succeeded in withdrawing for an inch or two, though the effort plainly caused him pain.

"That's right," added Melville, encouragingly; "we shall succeed—try it again."

There was a vigorous scraping, tugging, and pulling, and all at once the head and shoulders vanished through the window. Red Feather was released from the vice.

"There, I knew you would be all right!" called the lad through the opening. "Good-bye, Red Feather."

[37]The chief must have been not only confused and bewildered, but chagrined by the exhibition made before the lad and his own warriors, who, had they possessed any sense of humor, would have laughed at the sorry plight of their leader.

Stepping back from the window, so as not to tempt any shot from the other Sioux, all of whom had gathered about the chief, Melville found himself in a dilemma.

"Shall I take Red Feather at his word?" he asked himself; "shall I open the door and walk out with Dot, mount Saladin and gallop off to Barwell, or—wait?"

There is little doubt, from what followed, that the former would have been the wiser course of the youth. Despite the treacherous character of the Sioux leader, he was so relieved by his release from what he felt at the time was a fatal snare, and by the kindness received from the boy, that his heart was stirred by something akin to gratitude, and he would have restrained his warriors from violence.

Had Melville been alone, he would not have hesitated; but he was irresolute on account of Dot. Looking down in her sweet trustful face, his heart misgave him; he felt that, so long as she was with him, he could assume no risks. He was comparatively safe for a time in the building, while there was no saying what would follow if he should place himself and Dot in the power of Indians that had set out to destroy and slay.

Besides, if Red Feather meant to keep his promise he could do so without involving the brother and sister in the least danger. He had only to ride off with his warriors, when Melville would walk forth, call Saladin to him, mount, and ride away.

"If he is honest," was his decision, "he will do that; I will wait [38]until they are only a short distance off, and then will gallop to the settlement."

"Come," said he, taking the hand of Dot, "let's go upstairs."

"Why don't you stay down here, Mel?"

"Well, I am afraid to leave you alone because you are so apt to forget your promises to me; and since I want to go upstairs I must take you with me."

She made no objection, and holding Susie clasped by one arm, she placed the other hand in her brother's, and, side by side, the two walked up the steps to the larger room, occupied by their parents when at home.

"Now," said Melville, speaking with great seriousness, "you must do just as I tell you, Dot; for it you don't the bad Indians will surely hurt you, and you will never see Susie again."

She gave her pledge with such earnestness that he could depend upon her from that time forward.

"You must not go near the window unless I tell you to do so: the reason for that is that some of the Indians will see you, and they will fire their guns at you. If the bullet does not strike Dot and kill her, it will hit Susie, and that will be the last of her. The best thing you can do is to lie down on the bed and rest."

Dot obeyed cheerfully, reclining on the couch, with her round plump face against the pillow, where a few minutes later she sank into a sweet sleep. Poor child! little did she dream of what was yet to come.

She was safe so long as she remained thus, since, though a bullet fired through any one of the windows must cross the room, it would pass above the bed, missing her by several feet.[39]

Relieved of all present anxiety concerning her, Melville now gave [41]his attention to Red Feather and his warriors. That which he saw was not calculated to add to his peace of mind.

The chief and his five followers had re-mounted their ponies, and ridden to a point some two hundred yards distant on the prairie, where they halted, as if for consultation.

"Just what I feared," said the youth, feeling it safe to stand before the upper window and watch every movement; "Red Feather has already begun to repent of his pledge to me, and his warriors are trying to persuade him to break his promise. I don't believe they will find it hard work to change his mind."

But whatever was said, it was plain that the Sioux were much in earnest. All were talking, and their arms swung about their heads, and they nodded with a vigor that left no doubt all were taking part in the dispute, and each one meant what he said.

"Where there is so much wrangling, it looks as if some were in favor of letting us alone," thought Melville, who added the next minute—"I don't know that that follows, for it may be they are quarrelling over the best plan of slaying us, with no thought on the part of any one that they are bound in honor to spare us."

By-and-by the ponies, which kept moving uneasily about, took position so that the heads of all were turned fully or partly towards the building, from which the lad was attentively watching their movements.

During these exciting moments Melville did not forget Saladin. The sagacious animal, being no longer troubled by those that were so anxious to steal him, had halted at a distance of an eighth of a mile, where he was eating the grass as though there was nothing unusual in his surroundings.

[42]"I hope you will be wise enough, old fellow," muttered his young master, "to keep them at a distance; that shot couldn't have hit you, or, if it did, it caused nothing more than a scratch."

The horse's wisdom was tested the next minute. One of the warriors withdrew from the group, and began riding at a gallop towards Saladin. As he drew near he brought his pony down to a walk, and evidently hoped to calm the other's fears sufficiently to permit a still closer approach.

Melville's heart throbbed painfully as the distance lessened, and he began to believe he was to lose his priceless animal after all.

"Why didn't I think of it?" he asked himself, placing his finger in his mouth, and emitting a shrill whistle that could have been heard a mile distant.

It was a signal with which Saladin was familiar. He instantly raised his head and looked towards the house. As he did so he saw one of his mounted enemies slowly approaching, and within a dozen rods. It was enough, and breaking into a gallop, he quickly ended all hope of his capture by that Sioux brave.

That signal of Melville Clarendon had also been heard by all the Sioux, who must have thought it was due to that alone that the warrior failed to secure the valuable animal. The youth saw the group looking inquiringly at the house, as if to learn from what point the sound came, and the expression on the dark faces was anything but pleasing to him.

He wished to give Red Feather credit for the delay on the part of the Sioux. Their actions showed they were hotly disputing over something, and what more likely than that it was the question of assailing the house and outbuildings?

[43]But there were several facts against this theory. Red Feather held such despotic sway over his followers that it was hard to understand what cause could arise for any dispute with them about the disposal to be made of the brother and sister. If he desired to leave them alone, what was to prevent him riding off and obliging every one of his warriors to go with him?

This was the question which Melville continually asked himself, and which he could not answer as he wished, being unable to drive away the belief that the chief was acting a double part.

The Sioux had reached some decision; for, on the return of the one who failed to secure Saladin, they ceased disputing, and rode towards the window from which Melville was watching them.

Their ponies were on a slow walk, and the expression on their forbidding faces was plainly seen as their eyes ranged over the front of the building. The youth had withdrawn, so as to stand out of range; but, to end the doubt in his mind, he now stepped out in full view of every one of the warriors.

"Melville had warning enough to leap back."

"Melville had warning enough to leap back."

[44]The doubt was removed at once. Previous to this the lad had raised the lower sash, so as to give him the chance to fire, and as he stood, his waist and shoulders were in front of the upper part of the glass. It so happened that Red Feather and one of his warriors were looking at the very window at which he appeared. Like a flash both guns went to their shoulders and were discharged.

"He pointed his own weapon outward, and fired."

"He pointed his own weapon outward, and fired."

But Melville had enough warning to leap back, as the jingle and crash of glass showed how well the miscreants had aimed. Stirred to the deepest anger, he pointed his own weapon outward and fired into the party, doing so with such haste that he really took no aim at all.

It is not likely that his bullet had gone anywhere near the Sioux, [45]but it had served the purpose of warning them that he was as much in earnest as themselves.

Melville placed a cartridge in the breech of his rifle with as much coolness as a veteran, and prepared himself for what he believed was to be a desperate defence of himself and sister.

It must not be thought that he was in despair; for, when he came to look over the situation, he found much to encourage him. In the first place, although besieged by a half-dozen fierce Sioux, he was sure the siege could not last long. Whatever they did must be done within a few hours.

While it was impossible to tell the hour when his parents started from Barwell, it must have been quite early in the morning, and there was every reason to hope they would reach the settlement by noon at the latest. The moment they did so they would learn that Melville had left long before for home, and therefore had taken the upper trail, since, had he not done so, the parties would have met on the road.

True, Mr. Clarendon would feel strong hope that his son, being so well mounted, would wheel about and follow without delay the counsel in the letter; but he was too shrewd to rely fully on such hope. What could be more certain than that he would instantly gather a party of friends and set out to their relief?

The great dread of the youth was that the Sioux would set fire to the buildings, and he wondered many times that this was not done at the time Red Feather learned of the flight of the family.

Melville glanced at Dot, and, seeing she was asleep, he decided to go downstairs and make a fuller examination of the means of defence.

"Everything seems to be as secure as it can be," he said, standing [46]in the middle of the room and looking around; "that door has already been tried, and found not wanting. The only other means of entrance is through the windows, and after Red Feather's experience I am sure neither he nor any of his warriors will try that."

There were four windows—two at the front and two at the rear—all of the same shape and size. There was but the single door, of which so much has already been said, and therefore the lower portion of the building could not be made safer.

The stone chimney, so broad at the base that it was more than half as wide as the side of the outside wall, was built of stone, and rose a half-dozen feet above the roof. It was almost entirely out of doors, but was solid and strong.

"If the Indians were not such lazy people," said Melville—looking earnestly at the broad fire-place, in front of which stood the new-fashioned stove—"they might set to work and take down the chimney, but I don't think there is much danger of that."

He had hardly given expression to the thought when he fancied he heard a slight noise on the outside, and close to the chimney itself. He stepped forward, and held his ear to the stones composing the walls of the fire-place.

Still the sounds were faint, and he then touched his ear against them, knowing that solid substances are much better conductors of sound than air. He now detected the noise more plainly, but it was still so faint that he could not identify it.

He was still striving hard to do so when, to his amazement, Dot called him from above-stairs—

"Where are you, Mel? Is that you that I can hear crawling about over the roof?"

[47]CHAPTER FIVE

A STRANGE VISIT—OMINOUS SIGNS

MELVILLE Clarendon went up the short stairs three steps at a time, startled as much by the call of his sister as by anything that had taken place since the siege of the cabin began.

As he entered the room he saw Dot sitting up in bed, and staring wonderingly at the shivered window-glass, particles of which lay all around.

"Oh, Mel!" said she, "papa will scold you for doing that; how came you to do it?"

"It was the bad Indians who fired through the window at me, and I fired at them: you were sleeping so soundly that you only half awoke; but you must keep still a few minutes longer."

"I thought that was you on the roof," she added, in a lower voice.

That there was someone overhead was certain. The rasping sound of a person moving carefully along the peak of the roof was audible. The lad understood the meaning of that which puzzled him when on the lower floor: one of the warriors was carefully climbing the chimney—a task not difficult, because of its rough uneven formation.

The significance of such a strange act remained to be seen. It appeared unlikely that any of the Sioux were daring enough to attempt a descent of the chimney; but that such was really his purpose became clear within the following minute.

The Indian, after making his way a short distance along the peak, returned to the chimney, where, from the noises which reached the [48]listening ones, it was manifest that he was actually making his way down the flue, broad enough to admit the passage of a larger body than himself.

"I won't be caught foul this time," said Melville, turning to descend the stairs again; "Dot, stay right where you are on the bed till I come back or call to you."

She promised to obey, and there could be no doubt that she would do so.

"They must think I'm stupid," muttered the youth, taking his position in the middle of the room, with his rifle cocked and ready for instant use; "but they will find out the idiot is some one else."

He had not long to wait when in the large open space at the back of the stove appeared a pair of moccasins groping vaguely about for support. The pipe from the stove, instead of passing directly up the chimney, entered it by means of an elbow. Had it been otherwise, the daring warrior would have found himself in a bad fix on arriving at the bottom.

It would have been idle for the young man standing on the watch to fire at the feet or legs, and he waited an instant, when the Indian dropped lightly on his feet, and, without the least hesitation, stepped forward in the apartment and confronted Melville.

The latter was dumbfounded, for the first glance at his face showed that he was the chieftain Red Feather, the Indian whom of all others he least expected to see.

The act of the savage was without any possible explanation to the astonished youth, who, recoiling a step, stared at him, and uttered the single exclamation—

"Red Feather!"

[49]"Howly do, broder?" was the salutation of the Sioux, whose dusky face showed just the faintest smile.

Red Feather's descent of the chimney had not been without some disagreeable features. His blanket and garments, never very tidy, were covered with soot, enough of which had got on his face to suggest that he had adopted the usual means of his people to show they were on the war-path.

"A pair of moccasins groping vaguely about for support."

"A pair of moccasins groping vaguely about for support."

His knife and tomahawk were thrust in his girdle at his waist, and throughout this laborious task he had held his rifle fast, so that he was fully armed.

"Howly do?" he repeated, extending his hand, which Melville was too prudent to accept.

"No," he replied, compressing his lips, and keeping his finger on the trigger of his gun, "Red Feather speaks with a double tongue; he is not our friend."

"Red Feather been bad Injin—want white folks' scalp—don't want 'em now—little pappoose pray to Great Spirit—dat make Red [50]Feather feel bad—he hab pappoose—he lub Injin pappoose—lub white pappoose—much lub white pappoose."

This remark shed light upon the singular incident. To Melville it was a mystery beyond understanding that any person could look upon the sweet innocent face of Dot without loving her. Knowing how vile an Indian Red Feather had been, it was yet a question with the youth whether he could find it in his heart to wish ill to his wee bit of a sister.

Was it unreasonable, therefore, to believe that this savage warrior had been touched by the sight of the little one on her knees, with her hands clasped in prayer, and by her eagerness to keep away all harm from him?

This theory helped to explain what took place after the release of Red Feather from his odd imprisonment. The five warriors whom he had brought with him upon his raid must have combated his proposal to leave the children unharmed. In the face of his savage overbearing disposition they had fought his wish to keep the pledge to them, while he as firmly insisted upon its fulfilment.

But if such were the fact, how could his descent of the chimney be explained?

Melville did not try to explain it, for he had no time just then to speculate upon it; the explanation would come shortly.

The youth, however, was too wise to act upon that which he hoped was the truth. He had retreated nearly to the other side of the room, where he maintained the same defiant attitude as at first.

Red Feather read the distrust in his face and manner. With a deliberation that was not lacking in dignity, he walked slowly to the corner of the apartment, Melville closely following him with his eye, [51]and leaned his gun against the logs. Then he drew his knife and tomahawk from his girdle, and threw them on the floor beside the more valuable weapon. That done, he moved back to the fire-place, folded his arms, and, fixing his black eyes on the countenance of the lad, repeated—"Red Feather friend of white folk."

"I believe you," responded Melville, carefully letting down the hammer of his rifle and resting the stock on the floor; "now I am glad to shake hands with you."

A broader smile than before lit up the dusky face as the chief warmly pressed the hand of the youth, who felt just a little trepidation when their palms met.

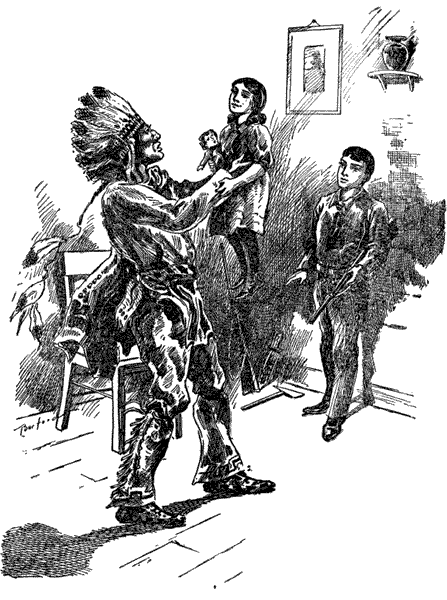

"Where pappoose?" asked Red Feather, looking suggestively at the steps leading to the upper story.

"Dot!" called Melville, "come down here; someone wants to see you."

The patter of feet was heard, and the next instant the little one came tripping downstairs, with her doll clasped by one arm to her breast.

"Red Feather is a good Indian now, and he wants to shake hands with you."

With a faint blush and a sweet smile Dot ran across the floor and held out her tiny hand. The chieftain stooped, and not only took the palm of the little girl, but placed each of his own under her shoulders and lifted her from the floor. Straightening up, he touched his dusky lips to those of the innocent one, murmuring, with a depth of emotion which cannot be described—

"Red Feather lub white pappoose—she make him good Injin—he be her friend always."

[52]The chieftain touched his lips but once to those of the little one, who showed no hesitation in accepting the salute. Pure, innocent, and good herself, she had not yet learned how evil the human heart may become.

Not only did she receive the salute willingly, but threw her free arm around the neck of the Indian and gave him a kiss.

"Red Feather, what made you come down the chimney?" questioned Melville when the Indian had released his sister.

"Can't come oder way," was the instant response.

"True; but why do you want to enter this house?"

"Be friend of white folk—come tell 'em."

"I am sure of that; but what can you do for us?"

Red Feather gave no direct answer to this question, but walked upstairs. As he did so he left every one of his weapons on the lower floor, and by a glance cast over his shoulder expressed the wish that the brother and sister should follow him. They did so, Dot tripping ahead, while Melville retained his weapons.

Reaching the upper floor, the Sioux walked directly to the window through which the shots had come that shattered the two panes of glass.

There was a curious smile on his swarthy face as he pointed at the pane on the left, and said—

"Red Feather fire dat!"

The explanation of his remark was that had Melville kept his place in front of the window at the moment the rifles were discharged, only one of the bullets would have hit him, and that would have been the one which Red Feather did not fire.[53]

The shot which he sent into the apartment, and which filled the [55]youth with so much indignation, had been fired for the purpose of making the other warriors believe the chieftain was as bitter an enemy of the brother and sister as he was of all white people.

Having convinced his followers on this point, he made his position still stronger with them by declaring his purpose of descending the chimney, and having it out with them, or rather with the lad, within the building.

Red Feather peered out of the window, taking care that none of his warriors saw him, though they must have felt a strong curiosity to learn the result of his strange effort to overcome the little garrison. Melville supposed that he had arranged to communicate with them by signal, for the result of the attempt must be settled quickly.

The youth took the liberty of peeping forth from the other window on the same side of the house.

Only two of the Sioux were in their field of vision, and their actions did not show that they felt much concern for their chief. They were mounted on their horses, and riding at a walk towards the elevations from which Red Feather had waved his blanket to the brother and sister when on the other side of the stream.

Melville's first thought was that they had decided to leave the place, but that hope was quickly dispelled by the action of the warriors. At the highest point of the hill they checked their ponies, and sat for a minute gazing fixedly to the northward in the direction of the settlement.

"They are looking for our friends," thought the youth, "but I am afraid they will not be in sight for a good while to come."

At this juncture one of the warriors deliberately rose to a standing position on the back of his pony, and turned his gaze to the westward.

[56]"Now they are looking for their friends," was the correct conclusion of Melville, "and I am afraid they see them; yes, there is no doubt of it."

The warrior, in assuming his delicate position, passed his rifle to his companion, whose horse was beside him. Then, with his two hands free, he drew his blanket from around his shoulders and began waving it, as Red Feather had done earlier in the day.

Melville glanced across at Red Feather, who was attentively watching the performance. He saw the countenance grow more forbidding, while a scowl settled on his brow.

It was easy to translate all this. The Sioux had caught sight of some of their friends, and signalled them. This would not have been done had there not been some person or persons to observe it.

The party which the chieftain had described as being in the Muddy Creek country must have changed their course and hastened to join Red Feather and the smaller party. If such were the fact, they would arrive on the spot within a brief space of time.

The interesting question arose whether, in the event of such arrival, and the attack that was sure to follow, Red Feather would come out as open defender of the children against his own people. Had there been only the five original warriors, he might have played a part something akin to neutrality, on the ground that his descent of the chimney had turned out ill for him, and, being caught at disadvantage he was held idle under the threat of instant death. Still further, it might have been his province to assume the character of hostage, and thus to defeat the overthrow of the couple by the Sioux.

But the arrival of the larger party would change everything. Among [57]the Muddy Creek band were several who disliked Red Feather intensely enough to be glad of a chance to help his discomfiture.

He had agreed that, in the event of his surprising the lad who was making such a brave defence, he would immediately appear at the front window and announce it, after which he would unbar the door and admit the warriors to the "last scene of all."

"'Let the Sioux send more of his warriors down the

chimney!'"

"'Let the Sioux send more of his warriors down the

chimney!'"

Several minutes had now passed, and no such announcement was made. The other three Sioux were lingering near the building, awaiting the signal which came not.

While the two were engaged on the crest of the hill the others suddenly came round in front of the house. They were on foot, and looked inquiringly at the windows, as if at a loss to understand the [58]cause of the silence. Red Feather instantly drew back, and said in a low voice to Melville—

"Speak to Injin—dem tink Red Feather lose scalp."

Grasping the situation, the youth showed himself at the window, where the Sioux were sure to see him, and uttered a tantalizing shout.

"Let the Sioux send more of their warriors down the chimney!" he called out; "the white youth is waiting for them, that he may take their scalps."

This was followed by another shout, as the lad withdrew beyond reach of a rifle-ball, that left no doubt of its meaning on the minds of the astounded warriors.

CHAPTER SIX

THE MUDDY CREEK BAND—THE TORCH

IT was easy for any spectator to interpret the actions and signals of the Sioux warrior who was standing erect on his pony and waving his blanket at some party invisible to the others.

After a minute or two he rested, with the blanket trailing beside him, while he still held his erect position, and continued gazing earnestly over the prairie. This showed that he was waiting for an answer to his signal. Either there was none, or that which was given was not satisfactory, for up went the blanket once more, and he swung it more vigorously than before, stopping and gazing away again.

This time the reply was what was desired, for the warrior dropped as suddenly astride of his horse as though his feet had been knocked [59]from under him, and, wheeling about, he and his companion galloped down the hill to where the others were viewing the cabin.

The taunting words which Melville had called through the front window must have convinced the Sioux that the pitcher had gone once too often to the fountain. Red Feather had escaped by a wonderful piece of good fortune when wedged in the window, and had been encouraged to another attempt, which ended in his ruin.

"Red Feather," said Melville, stepping close to the chieftain, who was still peering through one of the windows, "the other Sioux will soon be here."

"Dat so—dat so," replied the Indian, looking around at him and nodding his head several times.

"What will they do?"

"Standing erect and waving his blanket."

"Standing erect and waving his blanket."

Instead of replying to this question the chief seemed to be plunged in thought. He gazed fixedly in the face of the youth, as if uncertain what he ought to answer, and then he walked to the head of the stairs.

"Wait here—don't come."

And, without anything more, he went down the steps slowly, and without the slightest noise. Melville listened, but could hear nothing of his footfalls, though certain that he was moving across the floor.

[60]"I don't like this," muttered the lad, compressing his lips and shaking his head; "it makes me uneasy."

He was now in the lower story, where he left his rifle, knife, and tomahawk. He was therefore more fully armed than the youth, and, if he chose to play the traitor, there was nothing to prevent it.

It seemed to Melville that the coming of the larger party was likely to change whatever plans Red Feather might have formed for befriending him and his sister. What more probable than that he had decided to return to his first love?

But speculation could go on this way for ever, and without reaching any result.

"I'll do as I have done all along," he muttered; "I'll trust in Heaven and do the best I can. I'm sure of one thing," he added; "whatever comes, Red Feather won't hurt Dot: he has spared me on her account: and if he turns against me now, he will do what he can to save her. Therefore I'll make use of the little one."

Dot had held her peace through these trying moments, but he now called her to him and explained what he wished her to do. It was that she should place herself at the head of the stairs and watch Red Feather. In case he started to open the door, or to come up the stairs, she was to tell him. Dot was beginning to understand more clearly than before the situation in which she was placed. The belief that she could be of some use to her brother made her more anxious than ever to do her part. She walked to the head of the stairs and sat down where she could see what went on below.

Returning to his place at the window, Melville found enough to interest him without thinking of Red Feather.[61]

The band from the Muddy Creek country had just arrived, and [63]as nearly as he could judge, there were fully a score—all wild, ugly-looking fellows, eager for mischief. They had just galloped up the hill, where they gathered round the man that had first signalled them, he having ridden forward to meet them. They talked for several minutes, evidently to learn what had taken place in and around the Clarendon cabin.

This was soon made clear to them, and then the whole party broke into a series of yells enough to startle the bravest man. At the same time they began riding rapidly back and forth, swinging their rifles over their heads, swaying their bodies first on one side and then on another, and apparently growing more excited every minute.

At first they described short circles on the prairie, and then suddenly extended them so as to pass entirely around the house.

The Sioux, as they came in sight in front of the cabin, were in such a fire range that the youth felt sure he could bring down a warrior at every shot. He was tempted to do so, but restrained himself.

He reflected that, though several shots had been fired, no one, so far as he knew, had been hurt on either side. He had brought his own rifle to his shoulder more than once, and but a feather's weight more pressure on the trigger would have discharged it, but he was glad he had not done so.

"I shall not shoot any one," he said, determinedly, "until I see it must be done for the sake of Dot or myself. I wonder what Red Feather is at?"

Dot was still sitting at the head of the stairs, dividing her attention between Susie her doll and the chieftain. Stepping softly toward her, Melville asked—

"What is he doing, Dot?"

[64]"Nothing."

"Where is he standing?"

"Beside the front window, looking out just like you did a minute ago."

This was reassuring information, and helped to drive away the fear that had troubled the youth ever since the Sioux passed below stairs.

"Mel," called his sister the next minute, "I'm awful hungry; ain't it past dinner-time?"

"I'm afraid there is nothing to eat in the house."

"I'm awful thirsty, too."

"I feel a little that way myself, but I don't believe there is anything to eat or drink. You know, father and mother didn't expect us to stay here, or they would have left something for us."

"Can't I go downstairs and look?"

"Yes, if you will keep away from the windows, and tell Red Feather what you are doing."

"Hasn't he got eyes that he can see for himself?" asked the little one as she hurried down the steps.

The chief looked around when he heard the dainty steps, wondering what errand brought her downstairs.

"Red Feather," said the young lady, "I'm hungry; ain't you?"

"No—me no hungry," he answered, his dark face lighting up with pleasure at sight of the picture of innocence.

"Then you must have eaten an awful big breakfast this morning," remarked Dot, walking straight to the cupboard in the farther corner of the room, into which Melville had glanced when he first entered the house; "I know where mother keeps her jam and nice things."

[65]That she knew where the delicacies were stored Dot proved the next minute, when, to her delight, she found everything that heart, or rather appetite, could wish.

There were a jar of currant jam, a pan of cool milk, on which a thick crust of yellow cream had formed, three-fourths of a loaf of bread, and an abundance of butter. Good Mrs. Clarendon left them behind because she had an abundance without them. Little did she dream of the good service they were destined to do.

Dot uttered such a cry of delight that the chief walked toward her, and Melville seized the excuse to hurry below.

The first thing that struck him was that Red Feather's tomahawk and knife still lay in the corner where he had placed them. He simply held his rifle which most likely he was ready to use against his own people whenever the necessity arose.

"Well, Dot, you have found a prize," said her brother, following the chief, who was looking over her shoulder; "I had no idea that mother had left anything behind; there's enough for all."

She insisted that the others should partake while she waited, but neither would permit it. No matter how a-hungered either might have been, he enjoyed the sight of seeing her eat tenfold more than in partaking himself.

And you may be sure that Dot did ample justice to the rich find. Melville cut a thick slice for her, and spread the butter and jam on it, while a portion of the milk was poured into a cup.

I never heard of a little girl who could eat a piece of bread well covered with jam or preserves without failing to get most of it on her mouth. Dot Clarendon was no exception to the rule; and before she was through a goodly part of it, the sticky sweet stuff was on her [66]cheeks and nose. When she looked up at the two who were watching her, the sight was so comical that Red Feather did that which I do not believe he had done a dozen times in all his life—he threw back his head and laughed loud. Melville caught the contagion and gave way to his mirth, which was increased by the naive remark of Dot that she couldn't see anything to laugh at.

"He threw back his head and laughed loud."

"He threw back his head and laughed loud."

The appetite of the young queen having been satisfied, Melville insisted on Red Feather sharing what was left with him. The Sioux declined at first, but yielded, and the remaining bread and milk furnished them a grateful and nourishing repast. They did not use all, but saved enough to supply another meal for Dot, whose appetite was sure to make itself felt before many hours passed by.

Like most boys of his age in these later days, Melville Clarendon [67]carried a watch, which showed that it was past three o'clock in the afternoon. This was considerably later than he supposed, and proved that in the rush of incidents time had passed faster than he had suspected.

"What shall I do?" asked the youth, turning to the chief.

"Go—up up," he replied, pointing up the steps; "watch out. Red Feather—he watch out here."

"Do you want Dot to stay with you?" asked Melville, pausing on his way to the steps.

"Leave wid Red Feather—he take heap care ob pappoose."

"There can be no doubt of that," remarked the brother, as he bounded up the stairs, resuming his former station near the window.

Looking out with the same care he had shown from the first, he found the Sioux had grown tired of galloping round the house and buildings, or they were plotting some other kind of mischief, for only one of them was in sight.