« back

R M Ballantyne

"Under the Waves"

Preface.

This tale makes no claim to the character of an exhaustive illustration

I have to acknowledge myself indebted to the well-known submarine engineers Messrs Siebe and Gorman, and Messrs Heinke and Davis, of London, for much valuable information; and to Messrs Denayrouze, of Paris, for permitting me to go under water in one of their diving-dresses. Also—among many others—to Captain John Hewat, formerly Commander in the service of the Rajah of Sarawak, for much interesting material respecting the pirates of the Eastern Seas.

R.M.B. Edinburgh, 1876.

Chapter One.

Introduces our Hero, one of his Advisers, and some of his Difficulties.

“So, sir, it seems that you’ve set your heart on learning something of everything?”

The man who said this was a tall and rugged professional diver. He to whom it was said was Edgar Berrington, our hero, a strapping youth of twenty-one.

“Well—yes, I have set my heart upon something of that sort, Baldwin,” answered the youth. “You see, I hold that an engineer ought to be practically acquainted, more or less, with everything that bears, even remotely, on his profession; therefore I have come to you for some instruction in the noble art of diving.”

“You’ve come to the right shop, Mister Edgar,” replied Baldwin, with a gratified look. “I taught you to swim when you wasn’t much bigger than a marlinespike, an’ to make boats a’most before you could handle a clasp-knife without cuttin’ your fingers, an’ now that you’ve come to man’s estate nothin’ll please me more than to make a diver of you. But,” continued Baldwin, while a shade clouded his wrinkled and weatherbeaten visage, “I can’t let you go down in the dress without leave. I’m under authority, you know, and durstn’t overstep—”

“Don’t let that trouble you,” interrupted his companion, drawing a letter from his pocket; “I had anticipated that difficulty, and wrote to your employers. Here is their answer, granting me permission to use their dresses.”

“All right, sir,” said Baldwin, returning the letter without looking at it; “I’ll take your word for it, sir, as it’s not much in my line to make out the meanin’ o’ pot-hooks and hangers.—Now, then, when will you have your first lesson?”

“The sooner the better.”

“Just so,” said the diver, looking about him with a thoughtful air.

The apartment in which the man and the youth conversed was a species of out-house or lumber-room which had been selected by Baldwin for the stowing away of his diving apparatus and stores while these were not in use at the new pier which was in process of erection in the neighbouring harbour. Its floor was littered with snaky coils of india-rubber tubing; enormous boots with leaden soles upwards of an inch thick; several diving helmets, two of which were of brightly polished metal, while the others were more or less battered, dulled, and dinted by hard service in the deep. The walls were adorned with large damp india-rubber dresses, which suggested the idea of baby-giants who had fallen into the water and been sent off to bed while their costumes were hung up to dry. In one corner lay several of the massive breast and back weights by which divers manage to sink themselves to the bottom of the sea; in another stood the chest containing the air-pump by means of which they are enabled to maintain themselves alive in that uncomfortable position; while in a third and very dark corner, an old worn-out helmet, catching a gleam from the solitary window by which the place was insufficiently lighted, seemed to glare enviously out of its goggle-eyes at its glittering successors. Altogether, what with the strange spectral objects and the dim light, there was something weird in the aspect of the place, that accorded well with the spirit of young Berrington, who, being a hero and twenty-one, was naturally romantic.

But let us pause here to assert that he was also practical—eminently so. Practicality is compatible with romance as well as with rascality. If we be right in holding that romance is gushing enthusiasm, then are we entitled to hold that many methodical and practical men have been, are, and ever will be, romantic. Time sobers their enthusiasm a little, no doubt, but does by no means abate it, unless the object on which it is expended be unworthy.

Recovering from his thoughtful air, and repeating “Just so,” the diver added, “Well, I suppose we’d better begin wi’ them ’ere odds an’ ends about us.”

“Not so,” returned the youth quickly; “I have often seen the apparatus, and am quite familiar with it. Let us rather go to the pier at once. I’m anxious to go down.”

“Ah! Mister Edgar—hasty as usual,” said Baldwin, shaking his head slowly. “It’s two years since I last saw you, and I had hoped to find that time had quieted you a bit, but—. Well, well—now, look here: you think you’ve seen all my apparatus, an’ know all about it?”

“Not exactly all,” returned the youth, with a smile; “but you know I’ve often been in this store of yours, and heard you enlarge on most if not all of the things in it.”

“Yes—most, but not all, that’s where it lies, sir. You’ve often seen Siebe and Gorman’s dresses, but did you ever see this helmet made by Heinke and Davis?”

“No, I don’t think I ever did.”

“Or that noo helmet wi’ the speakin’-toobe made by Denayrouze and Company, an’ this dress made by the same?”

“No, I’ve seen none of these things, and certainly this is the first time I have heard of a speaking-tube for divers.”

“Well then, you see, Mister Edgar, you have something to larn here after all; among other things, that Denayrouze’s is not the first speakin’-toobe,” said Baldwin, who thereupon proceeded with the most impressive manner and earnest voice to explain minutely to his no less earnest pupil the various clever contrivances by which the several makers sought to render their apparatus perfect.

With all this, however, we will not trouble the reader, but proceed at once to the port, where diving operations were being carried on in connection with repairs to the breakwater.

On their way thither the diver and his young companion continued their conversation.

“Which of the various dresses do you think the best?” asked Edgar.

“I don’t know,” answered Baldwin.

“Ah, then you are not bigotedly attached to that of your employer—like some of your fraternity with whom I have conversed?”

“I am attached to Siebe and Gorman’s dress,” returned Baldwin, “but I am no bigot. I believe in every thing and every creature having good and bad points. The dress I wear and the apparatus I work seem to me as near perfection as may be, but I’ve lived too long in this world to suppose nobody can improve on ’em. I’ve heard men who go down in the dresses of other makers praise ’em just as much as I do mine, an’ maybe with as good reason. I believe ’em all to be serviceable. When I’ve had more experience of ’em I’ll be able to say which I think the best.—I’ve got a noo hand on to-day,” continued Baldwin, “an’ as he’s goin’ down this afternoon for the first time, so you’ve come at a good time. He’s a smart young man, but I’m not very hopeful of him, for he’s an Irishman.”

“Come, old fellow,” said Edgar, with a laugh, “mind what you say about Irishmen. I’ve got a dash of Irish blood in me through my mother, and won’t hear her countrymen spoken of with disrespect. Why should not an Irishman make a good diver?”

“Because he’s too excitable, as a rule,” replied Baldwin. “You see, Mister Edgar, it takes a cool, quiet, collected sort of man to make a good diver, and Irishmen ain’t so cool as I should wish. Englishmen are better, but the best of all are Scotchmen. Give me a good, heavy, raw-boned lump of a Scotchman, who’ll believe nothin’ till he’s convinced, and accept nothin’ till it’s proved, who’ll argue with a stone wall, if he’s got nobody else to dispute with, in that slow sedate humdrum way that drives everybody wild but himself, who’s got an amazin’ conscience, but no nerves whatever to speak of—ah, that’s the man to go under water, an’ crawl about by the hour among mud and wreckage without gittin’ excited or makin’ a fuss about it if he should get his life-line or air-toobe entangled among iron bolts, smashed-up timbers, twisted wire-ropes, or such like.”

“Scotchmen should feel complimented by your opinion of them,” said Edgar.

“So they should, for I mean it,” replied Baldwin, “but I hope the Irishman will turn up a trump this time.—May I take the liberty of askin’ how you’re gittin’ on wi’ the engineering, Mister Edgar?”

“Oh, famously. That is to say, I’ve just finished my engagement with the firm of Steel, Bolt, Hardy, and Company, and am now on the point of going to sea.”

Baldwin looked at his companion in surprise. “Going to sea!” he repeated, “why, I thought you didn’t like the sea?”

“You thought right, Baldwin, but men are sometimes under the necessity of submitting to what they don’t like. I have no love for the sea, except, indeed, as a beautiful object to be admired from the shore, but, you see, I want to finish my education by going a voyage as one of the subordinate engineers in an ocean-steamer, so as to get some practical acquaintance with marine engineering. Besides, I have taken a fancy to see something of foreign parts before settling down vigorously to my profession, and—”

“Well?” said Baldwin, as the youth made rather a long pause.

“Can you keep a secret, Baldwin, and give advice to a fellow who stands sorely in need of it?”

The youth said this so earnestly that the huge diver, who was a sympathetic soul, declared with much fervour that he could do both.

“You must know, then,” began Edgar with some hesitation, “the fact is—you’re such an old friend, Baldwin, and took such care of me when I was a boy up to that sad time when I lost my father, and you lost an employer—”

“Ay, the best master I ever had,” interrupted the diver.

“That—that I think I may trust you; in short, Baldwin, I’m over head and ears with a young girl, and—and—”

“An’ your love ain’t requited—eh?” said Baldwin interrogatively, while his weatherbeaten face elongated.

“No, not exactly that,” rejoined Edgar, with a laugh. “Aileen loves me almost, I believe, as well as I love her, but her father is dead against us. He scorns me because I am not a man of wealth.”

“What is he?” demanded Baldwin.

“A rich China merchant.”

“He’s more than that,” said Baldwin.

“Indeed!” said Edgar, with a surprised look; “what more is he?”

“He’s a goose!” returned the diver stoutly.

“Don’t be too hard on him, Baldwin. Remember, I hope some day to call him father-in-law. But why do you hold so low an opinion of him?”

“Why, because he forgets that riches may, and often do, take to themselves wings and fly away, whereas broad shoulders, and deep chest, and sound limbs, and a good brain, usually last the better part of a lifetime; and a brave heart will last for ever.”

“I am afraid that I have yet to prove, to myself as well as to the old gentleman, that the brave heart is mine,” returned Edgar. “As to the physique—you may be so far right, but he evidently undervalues that.”

“I said nothing about physic,” returned Baldwin, who still frowned as he thought of the China merchant, “and the less that you and I have to do wi’ that the better. But what are you goin’ to do, sir?”

“That is just the point on which I want to have your advice. What ought I to do?”

“Don’t run away with her, whatever you do,” said Baldwin emphatically.

The youth laughed slightly as he explained that there was no chance whatever of his doing that, because Aileen would never consent to run away or to disobey her father.

“Good—good,” said the diver, with still greater emphasis than before, “I like that. The gal that would sacrifice herself and her lover sooner than disobey her father—even though he is a goose—is made o’ the right stuff. If it’s not takin’ too great a liberty, Mister Edgar, may I ask what she’s like?”

“What she’s like—eh?” murmured the other, dropping his head as if in reverie, and stroking the dark shadow on his chin which was beginning to do duty for a beard. “Why, she—she’s like nothing that I ever saw on earth before.”

“No!” ejaculated Baldwin, elevating his eyebrows a little, as he said gravely, “what, not even like an angel?”

“Well, yes; but even that does not sufficiently describe her. She’s fair,”—he waxed enthusiastic here,—“surpassingly fair, with wavy golden tresses and blue eyes, and a bright complexion and a winning voice, and a sylph-like figure and a thinnish but remarkably pretty face—”

“Ah!” interrupted Baldwin, with a sigh, “I know: just like my missus.”

“Why, my good fellow,” cried Edgar, unable to restrain a fit of laughter, “I do not wish to deny the good looks of Mrs Baldwin, but you know that she’s uncommonly ruddy and fat and heavy, as well as fair.”

“Ay, an’ forty, if you come to that,” said the diver. “She’s fourteen stun if she’s an ounce; but let me tell you, Mister Edgar, she wasn’t always heavy. There was a time when my Susan was as trim and taut and clipper-built as any Aileen that ever was born.”

“I have no doubt of it whatever,” returned the youth, “but I was going to say, when you interrupted me, it is her eyes that are her strong point—her deep, liquid, melting blue eyes, that look at you so earnestly, and seem to pierce—”

“Ay, just so,” interrupted the diver; “pierce into you like a gimblet, goin’ slap agin the retina, turnin’ short down the jugular, right into the heart, where they create an agreeable sort o’ fermentation. Oh! Don’t I know?—my Susan all over!”

Edgar’s amusement was tinged slightly with disgust at the diver’s persistent comparisons. However, mastering his feelings, he again demanded advice as to what he should do in the circumstances.

“You han’t told me the circumstances yet,” said the diver quietly.

“Well, here they are. Old Mr Hazlit—”

“What! Hazlit? Miss Hazlit, is that her name?” cried Baldwin, with a look of pleased surprise.

“Yes, do you know her?”

“Know her? Of course I do. Why, she visits the poor in my district o’ the old town—you know I’m a local preacher among the Wesleyans—an’ she’s one o’ the best an’ sweetest—ha! Angel indeed! I’m glad she wasn’t made an angel of, for it would have bin the spoilin’ of a splendid woman. Bless her!”

The diver spoke with much enthusiasm, and the young man smiled as he said, “Of course I add Amen to your last words.—Well then,” he continued, “Aileen’s father has refused to allow me to pay my addresses to his daughter. He has even forbidden me to enter his house, or to hold any intercourse whatever with her. This unhappy state of things has induced me to hasten my departure from England. My intention is to go abroad, make a fortune, and then return to claim my bride, for the want of money is all that the old gentleman objects to. I cannot bear the thought of going away without saying good-bye, but that seems now unavoidable, for he has, as I have said, forbidden me the house.”

Edgar looked anxiously at his companion’s face, but received no encouragement there, for Baldwin kept his eyes on the ground, and shook his head slowly.

“If the old gentleman has forbid you his house, of course you mustn’t go into it. However, it seems to me that you might cruise about the house and watch till Sus— Aileen, I mean—comes out; but I don’t myself quite like the notion of that either, it don’t seem fair an’ above-board like.”

“You are right,” returned Edgar. “I cannot consent to hang about a man’s door, like a thief waiting to pounce on his treasure when it opens. Besides, he has forbidden Aileen to hold any intercourse with me, and I know her dear nature too well to subject it to a useless struggle between duty and inclination. She is certain to obey her father’s orders at any cost.”

“Then, sir,” said Baldwin decidedly, “you’ll just have to go afloat without sayin’ good-bye. There’s no help for it, but there’s this comfort, that, bein’ what she is, she’ll like you all the better for it.—Now, here we are at the pier. Boat a-hoy-oy!”

In reply to the diver’s hail a man in a punt waved his hand, and pulled for the landing-place.

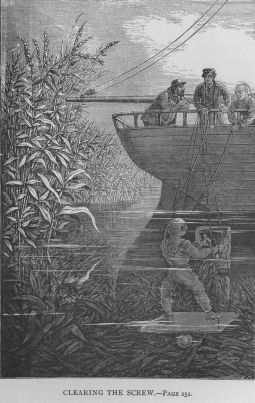

A few strokes of the oar soon placed them on the deck of a large clumsy vessel which lay anchored off the entrance to the harbour. This was the diver’s barge, which exhibited a ponderous crane with a pendulous hook and chain in the place where its fore-mast should have been. Several men were busied about the deck, one of whom sat clothed in the full dress of a diver, with the exception of the helmet, which was unscrewed and lay on the deck near his heavily-weighted feet. The dress was wet, and the man was enjoying a quiet pipe, from all which Edgar judged that he was resting after a dive. Near to the plank on which the diver was seated there stood the chest containing the air-pumps. It was open, the pumps were in working order, with two men standing by to work them. Coils of india-rubber tubing lay beside it. Elsewhere were strewn about stones for repairing the pier, and various building tools.

“Has Machowl come on board yet?” asked Baldwin, as he stepped on the deck. “Ah, I see he has.—Well, Rooney lad, are you prepared to go down?”

“Yis, sur, I am.”

Rooney Machowl, who stepped forward as he spoke, was a fine specimen of a man, and would have done credit to any nationality. He was about the middle height, very broad and muscular, and apparently twenty-three years of age. His countenance was open, good-humoured, and good-looking, though by no means classic—the nose being turned-up, the eyes small and twinkling, and the mouth large.

“Have you ever seen anything of this sort before?” asked Baldwin, with a motion of his hand towards the diving apparatus scattered on the deck.

“No sur, nothin’.”

“Was you bred to any trade?”

“Yis, sur, I’m a ship-carpenter.”

“An’ why don’t you stick to that?”

“Bekase, sur, it won’t stick to me. There’s nothin’ doin’ apparently in this poort. Annyhow I can’t git work, an’ I’ve a wife an’ chick at home, who’ve bin so long used to praties and bacon that their stummicks don’t take kindly to fresh air fried in nothin’. So ye see, sur, findin’ it difficult to make a livin’ above ground, I’m disposed to try to make it under water.”

While Rooney Machowl was speaking Baldwin regarded him with a fixed and critical gaze. What his opinion of the recruit was did not, however, appear on his countenance or in his reply, for he merely said, “Humph! Well, we’ll see. You’ll begin your education in your noo profession by payin’ partikler attention to all that is said an’ done around you.”

“Yis, sur,” returned Machowl, respectfully touching the peak of his cap and wrinkling his forehead very much, while he looked on at the further proceedings of the divers with that expression of deep earnest sincerity of attention which—whether assumed or genuine—is only possible to the countenance of an Irishman.

During this colloquy the two men standing by the pump-case, and two other men who appeared to be supernumeraries, listened with much interest, but the diver seated on the plank, resting and calmly smoking his pipe, gazed with apparent indifference at the sea, from which he had recently emerged.

This man was a very large fellow, with a dark surly countenance—not exactly bad in expression, but rather ill-tempered-looking. His diving-dress being necessarily very wide and baggy, made him seem larger than he really was—indeed, quite gigantic. The dress was made of very thick india-rubber cloth, and all—feet, legs, body, and arms—was of one piece, so perfectly secured at the seams as to be thoroughly impervious to air or water. To get into it was a matter of some difficulty, the entrance being effected at the neck. When this neck is properly attached to the helmet, the diver is thoroughly cut off from the external world, except through the air-tube communicating with his helmet and the pump afore mentioned.

“Have ye got the hole finished, Maxwell?” said Baldwin, turning to the surly diver.

“Yes,” he replied shortly.

“Well, then, go down and fix the charge. Here it is,” said Baldwin, taking from a wooden case an object about eighteen inches long, which resembled a large office-ruler that had been coated thickly with pitch. It was an elongated shell filled to the muzzle with gunpowder. To one end of it was fastened the end of a coil of wire which was also coated with some protecting substance.

As Baldwin spoke Maxwell slowly puffed the last “draw” from his lips and knocked the ashes out of his pipe on the plank, on which he still remained seated while the two supernumeraries busied themselves in completing his toilet for him; one screwing on his helmet, which appeared ridiculously large, the other loading his breast and back with two heavy leaden weights. When fully equipped, the diver carried on his person a weight fully equal to that of his own bulky person.

“Now look here, Mister Edgar, an’ pay partikler attention, Rooney Machowl. This here toobe, made of indyrubber, d’ee see? (‘Yis, sur,’ from Rooney) I fix on, as you perceive, to the back of Maxwell’s helmet. It communicates with that there pump, and when these two men work the pump, air will be forced into the helmet and into the dress down to his very toes. We could bu’st him, if we were so disposed, if it wasn’t for an escape-valve, here close beside the air-toobe, at the back of the helmet, which keeps lettin’ off the surplus air. Moreover, there is another valve, here in front of the breast-plate, which is under the control of the diver, so that he can let air escape by givin’ it a half-turn when the men at the pumps are givin’ him too much, or he can keep it in when they’re givin’ him enough.”

“An’ what does he do,” asked Rooney, with an anxious expression, “whin they give him too little?”

“He pulls on the air-pipe,—as I’ll explain to you in good time—the proper signal for ‘more air.’”

“But what if he forgits, or misremimbers the signal?” asked the inquisitive recruit.

“Why then,” replied Baldwin, “he suffocates, and we pull him up dead, an’ give him decent burial. Keep yourself easy, my lad, an’ you’ll know all about it in good time. I’ll soon give ’ee the chance to suffocate or bu’st yourself accordin’ to taste.”

“Come, cut it short and look alive,” said Maxwell gruffly, as he stood up to permit of a stout rope being fastened to his waist.

“You shut up!” retorted Baldwin.

Having exchanged these little civilities the two divers moved to the side of the barge—Maxwell with a slow ponderous tread.

A short iron ladder dipped from the gunwale of the barge a few feet down into the sea. The diver stepped upon this, turning with his face inwards, descended knee-deep into the water, and then stopped. Baldwin handed him the blasting-charge. At the same moment one of the supernumeraries advanced with the front-glass or bull’s-eye in his hand, and the men at the pumps gave a turn or two to see that all was working well.

“All right?” demanded the supernumerary.

“Right,” responded Maxwell, in a voice which issued sepulchrally from the iron globe.

There are three round windows fitted with thick plate-glass in the helmets to which we refer. The front one is made to screw off and on, and the fixing of this is always the last operation in completing a diver’s toilet.

“Pump away,” said the man, holding the round glass in front of Maxwell’s nose, and looking over his shoulder to see that the order was obeyed. The glass was screwed on, and the man finished off by gravely patting Maxwell in an affectionate manner on the head.

“Why does he pat him so?” asked Edgar, with a laugh at the apparent tenderness of the act.

“It’s a tinder farewell, I suppose,” murmured Rooney, “in case he niver comes up again.”

“It is to let him know that he may now descend in safety,” answered Baldwin. “The pump there is kep’ goin’ from a few moments before the front-glass is screwed on till the diver shows his head above water again—which he’ll do in quarter of an hour or so, for it don’t take long to lay a charge; but our ordinary spell under water, when work is steady, is about four hours—more or less—with perhaps a breath of ten minutes once or twice at the surface when they’re working deep.”

“But why a breath at the surface?” asked Edgar. “Isn’t the air sent down fresh enough?”

“Quite fresh enough, Mister Edgar, but the pressure when we go deep—say ten or fifteen fathoms—is severe on a man if long continued, so that he needs a little relief now and then. Some need more and some less relief, accordin’ to their strength. Maxwell has only gone down fifteen feet, so that he wouldn’t need to come up at all durin’ a spell of work. We’re goin’ to blast a big rock that has bin’ troublesome to us at low water. The hole was driven in it last week. We moored a raft over it and kep’ men at work with a long iron jumper that reached from the rock to the surface of the sea. It was finished last night, and now he’s gone to fix the charge.”

“But I don’t understand about the pressure, sur, at all at all,” said Machowl, with a complicated look of puzzlement; “sure whin I putt my hand in wather I don’t feel no pressure whatsomediver.”

“Of course not,” responded Baldwin, “because you don’t put it deep enough. You must know that our atmosphere presses on our bodies with a weight of about 20,000 pounds. Well, if you go thirty-two feet deep in the sea you get the pressure of exactly another atmosphere, which means that you’ve got to stand a pressure all over your body of 40,000 when you’ve got down as deep as thirty-two feet.”

“But,” objected Rooney, “I don’t fed no pressure of the atmosphere on me body at all.”

“That’s because you’re squeezed by the air inside of you, man, as well as by the atmosphere outside, which takes off the feelin’ of it, an’, moreover, you’re used to it. If the weight of our atmosphere was took off your outside and not took off your inside—your lungs an’ the like,—you’d come to feel it pretty strong, for you’d swell like a balloon an’ bu’st a’most, if not altogether.”

Baldwin paused a moment and regarded the puzzled countenance of his pupil with an air of pity.

“Contrairywise,” he continued, “if the air was all took out of your inside an’ allowed to remain on your outside, you’d go squash together like a collapsed indyrubber ball. Well then, if that be so with one atmosphere, what must it be with a pressure equal to two, which you have when you go down to thirty-two feet deep in the sea? An’ if you go down to twenty-five fathoms, or 150 feet, which is often done, what must the pressure be there?”

“Tightish, no doubt,” said Rooney.

“True, lad,” continued Joe. “Of course, to counteract this we must force more air down to you the deeper you go, so that the pressure inside of you may be a little more than the pressure outside, in order to force the foul air out of the dress through the escape-valve; and what between the one an’ the other your sensations are peculiar, you may be sure.—But come, young man, don’t be alarmed. We’ll not send you down very deep at first. If some divers go down as deep as twenty-five fathoms, surely you’ll not be frightened to try two and a half.”

Whatever Rooney’s feelings might have been, the judicious allusion to the possibility of his being frightened was sufficient to call forth the emphatic assertion that he was ready to go down two thousand fathoms if they had ropes long enough and weights heavy enough to sink him!

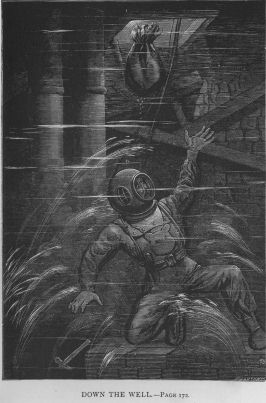

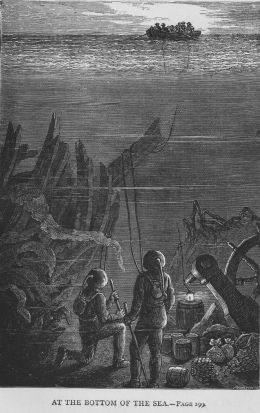

While the recruit is preparing for his subaqueous experiments, you and I, reader, will go see what Maxwell is about at the bottom of the sea.

Chapter Two.

Describes a first Visit to the Bottom of the Sea.

When the diver received the encouraging pat on the head, as already related, he descended the ladder to its lowest round. Here, being a few feet below the surface, the buoyancy of the water relieved him of much of the oppression caused by the great weights with which he was loaded. He was in a semi-floating condition, hence the ladder, being no longer necessary, was made to terminate at that point. He let go his hold of it and sank gently to the bottom, regulating his pace by a rope which descended from the foot of the ladder to the mud, on which in a few seconds his leaden soles softly rested. A continuous stream of air-bubbles from the safety-valve behind the helmet indicated to those above that the pumps were doing their duty, and at the same time hid the diver entirely from their sight.

Meanwhile the two men who acted as signalman and assistant stood near the head of the ladder, the first holding the life-line, the assistant the coil of air-tubing. Their duty was to stand by and pay out or haul in tubing and line according as the diver’s movements and necessities should require. They were to attend also to his signals—some of which were transmitted by the line and some by the air-tube. These signals vary among divers. With Baldwin and his party one pull on the life-line meant “All right;” four pulls, “I’m coming up.” One pull on the air-pipe signified “Sufficient air;” two pulls, “More air.” (pump faster.) Four pulls was an alarm, and signified “Haul me up.” The aspect of Rooney Machowl’s face when endeavouring to understand Baldwin’s explanation of these signals was a sight worth seeing!

But to return to our diver. On reaching the bottom, Maxwell took a coil of small line which hung on his left arm, and attached one end of it to a stone or sinker which kept taut the ladder-line by which he had descended. This was his clew to guide him back to the ladder. Not only is the light under water very dim—varying of course, according to depth, until total darkness ensues—but a diver’s vision is much weakened by the muddy state of the water at river-mouths and in harbours, so that he is usually obliged to depend more on feeling than on sight. If he were to leave the foot of his ladder without the guiding-coil, it would be difficult if not impossible to find it again, and his only resource would be to signal “Haul me up,” which would be undignified, to say the least of it! By means of this coil he can wander about at will—within the limits of his air-tube tether of course,—and be certain to find his way back to the ladder-foot in the darkest or muddiest water.

Having fastened the line, the diver walked in the direction of the rock on which he had to operate, dropping gradually the coils of the guiding-line as he proceeded. His progress was very slow, for water is a dense medium, and man’s form is not well adapted for walking in it—as every bather knows who has attempted to walk when up to his neck in it. He soon found the object of his search, and went down on his knees beside the hole already driven into the rock. Even this process of going on his knees was not so simple as it sounds, for the men above were sending down more air than could escape by the valve behind the helmet, and thus were filling his dress to such an extent that he had a tendency to rise off the ground despite his weights. To counteract this he opened the valve in front, let out the superabundant air, got on his knees, and was soon busy at work inserting the charge-tube into the hole and tamping it well home, taking care that the fine wire with which it communicated with the party in the barge should not be injured.

While thus engaged he was watched, apparently with deep interest, by a small crab, a shrimp, and several little fish of various kinds, all of which we may add, seemed to have various degrees of curiosity. One particular little fish, named a goby, and celebrated for its wide-awake nature and impudence, actually came to the front-glass of the helmet and looked in. But the diver was too busy to pay attention to it. Nothing abashed, the goby went to each of the side-windows, but, receiving no encouragement, it made for a convenient ledge of the rock, where, resting its fore-fins on a barnacle, it turned its head a little on one side and looked on in silence. Finding this rather tedious, after a time it went, with much of the spirit of a London street-boy, and, passing close to the shrimp, tweaked the end of one of its feelers, causing that volatile creature to vanish. It then made a demonstration of attack on the crab, but that crustaceous worthy, sitting up on its hind-legs and expanding both claws with a very “come-on-if-you-dare” aspect, bid it defiance.

Meanwhile the charge was laid, and Maxwell rose to return to the world above. Feeling a certain uncomfortable hotness in the air he breathed, and observing that his legs were remarkably thin, and that his dress was clasped somewhat too lovingly about his person, he became aware of the fact that, having neglected to reclose the front-valve, his supply of air was now insufficient. He therefore shut the valve and began to wend his way back to the ladder. By the time he reached it the air in his dress had swelled him out to aldermanic dimensions, so that he pulled himself up the ladder-rope, hand over hand, with the utmost ease—having previously given four pulls on his life-line to signal “coming up.” A few seconds more and his head was seen to emerge from the surface, like some goggle-eyed monster of the briny deep.

A comrade at once advanced and unscrewed his front-glass, and then, but not till then, did the men at the pumps cease their labours.

“All right,” said Maxwell, stepping over the side and seating himself on his plank.

“Stand by,” said Baldwin.

The two satellites did not require that order, for they were already standing by with a small electrical machine. The wire before mentioned as being connected with the charge of powder, now safely lodged in the hole at the bottom of the sea, was connected with the electrical machine, and a few vigorous turns of its handle were given, while every eye was turned expectantly on the surface of the sea.

That magic spark which now circles round the world, annihilating time and space, was evolved; it flashed down the wire; the ocean could not put it out; the dry powder received it; the massive rock burst into fragments; a decided shock was felt on board the barge, and a turmoil of gas-bubbles and dead or dying fish came to the surface, in the midst of which turmoil the shrimp, the crab, and the goby doubtless came to an untimely end.

Thus was cleared out of the way an obstruction which had from time immemorial been a serious inconvenience to that port; and thus every year serious inconveniences and obstructions that most people know very little about are cleared out of the way by our bold, steady, and daring divers, through the wisdom and the wonderful appliances of our submarine engineers.

“Now then, Rooney, come an’ we’ll dress you,” said Baldwin. “As you’re goin’ to be a professional diver it’s right that you should have the first chance and set a good example to Mister Berrington here, who’s only what we may call an amateur.”

“Faix, I’d rather that Mister Berrington shud go first,” said Rooney, who, as he spoke, however, stripped himself of his coat, vest, and trousers preparatory to putting on the costume.

“I’ll be glad to go first, Rooney, if you’re afraid,” said Edgar.

Rooney’s annoyance at being thought afraid was increased to indignation by a contemptuous guffaw from Maxwell.

Flushing deeply and casting a glance of anger at Maxwell, the young Irishman crushed down his feelings and said—

“Sure, I’m only jokin’. Put on the dress Mister Baldwin av ye plaze.”

A diver, like a too high-bred lady, cannot well dress himself. He requires two assistants. Rooney Machowl sat down on the plank beside Maxwell, who was busy taking off his dress, and acted according to orders.

First of all they brought him a thick guernsey shirt, a pair of drawers and pair of inside stockings, which he put on and fastened securely. Sometimes a “crinoline” to afford protection to the stomach in deep water is put on, but on the present occasion it was omitted, the water being shallow. Then Baldwin put on him a “shoulder-pad” to bear the weight of the helmet, etcetera, and prevent chafing.

“If it was cold, Rooney,” said his instructor, “I’d put two guernseys and pairs of drawers and stockin’s on you, but, as it’s warm, one set’ll do. Moreover, if you was goin’ deep you’d have the option of stuffin’ your ears with cotton soaked in oil, to relieve the pressure; some do an’ some don’t. I never do myself. It’s said to relieve the pressure of air on the ears, but my ears are strong. Anyway you won’t want it in this water.—Now for the dress, boys.”

The two assistants—with mouths expanded from ear to ear—here advanced with the strong india-rubber garment whose legs, feet, body, and arms are, as we have already said, all in one piece. Pushing his feet in at the upper opening, Rooney writhed, thrust, and wriggled himself into it, being ably assisted by his attendants, who held open the sleeves for him and expanded the tight elastic cuffs, and, catching the dress at the neck, hitched it upwards so powerfully as almost to lift their patient off his legs. Next, came a pair of outside stockings and canvas overalls or short trousers, both of which were meant to preserve the dress-proper from injury. Having been got into all these things, Rooney was allowed to sit down while his attendants each put on and buckled a boot with leaden soles—each boot weighing about twenty pounds.

“A purty pair of dancin’ pumps!” remarked Rooney, turning out his toes, while Baldwin put on his breast-plate, after having drawn up the inner collar of the dress and tied it round his neck with a piece of spare yarn.

The breast-plate was made of tinned copper. It covered part of the back, breast, and shoulders of the diver, and had a circular neck, to which the helmet was to be ultimately screwed. It rested on the inner collar of the dress, and the outer collar—of stout india-rubber—was drawn over it. In this outer collar were twelve holes, corresponding to twelve screws round the edge of the breast-plate. When these holes had been fitted over their respective screws, a breast-plate-band, in four pieces, was placed over them and screwed tight by means of nuts—thus rendering the connection between the dress and the breast-plate perfectly water-tight. It now only remained to screw the helmet to the circular neck of the breast-plate. Previously, however, a woollen night-cap was drawn over the poor man’s head, well down on his ears, and Rooney looked—as indeed he afterwards admitted that he felt—as if he were going to be hanged. He thought, however, of the proverb, that a man who is born to be drowned never can be hanged, and somehow felt comforted.

The diving helmet is made of tinned copper, and much too large for the largest human head, in order that the wearer may have room to move his head freely about inside of it. It should not touch the head in any part, but is fixed rigidly to the breast-plate, resting on the shoulders, and does not partake of the motions of the head. In it are three round openings filled with the thickest plate-glass and protected by brass bars or guards; also an outlet-valve to allow the foul air to escape; a short metal tube with an inlet-valve, to which the air-pump is screwed; and a regulating cock for getting rid of excess of air. The arrangement is such, that the fresh air enters, and is spread over the front of the diver’s face, while the foul escapes at the back of his head. By a clever contrivance—a segmental screw—the helmet can be fixed to its neck with one-eighth of a turn, instead of having to be twisted round several times. To various hooks and studs on the helmet and breast-plate are hung two leaden masses weighing about forty pounds each.

These weights having been attached, and a waist-belt with a knife in it put round Rooney’s waist, along with the life-line, the air-tube was affixed, and he was asked by Baldwin how he felt.

“A trifle heavy,” replied the pupil, through the front hole of the helmet, which was not yet closed.

“That feeling will go off entirely when you’re under water,” said Baldwin. “Now, remember, if you want more air, just give two pulls on the air-pipe—an’ don’t pull as if you was tryin’ to haul down the barge; we’ll be sure to feel you. Be gentle and quiet, whatever ye do. Gettin’ flurried never does any good whatever. D’ee hear?”

“Yis, sur,” answered Rooney, and his voice sounded metallic and hollow, even to those outside—much more so to himself!

“Well, then, if we give you too much air, you’ve only got to open the front-valve—so, and, when you’re easy, shut it. When you get down to the bottom, give one—only one—pull on the life-line, which means ‘All right,’ and I’ll give one pull in reply. We must always reply to each other, d’ee see? because if you don’t answer, of course we’ll think you’ve been suffocated, or entangled at the bottom among wreckage and what-not, or been took with a fit, an’ we’ll haul you up, as hard as we can; so you’ll have to be particular. D’ee understand?”

Again the learner replied “Yis, sur,” but less confidently than before, for Baldwin’s cautions, although meant to have an encouraging effect, proved rather to be alarming.

“Now,” continued the teacher, leading his pupil to the side of the barge, “be sure to go down slow, and come up slow. Whatever you do, do it slow, for if you do it fast—especially in comin’ up—you’ll come to grief. If a man comes up too fast from deep water, the condensed air inside of him is apt to swell him out, and the brain bein’ relieved too suddenly from the pressure, there’s a rush of blood to it, and a singin’ in the ears, and a pain in the head, with other unpleasant symptoms. Why,” continued Baldwin, growing energetic, “I’ve actually known a man killed outright by bein’ pulled up too quick from a depth of twenty fathoms. So mark my words, lad, and take it easy. If you get nervous, just stop a bit an’ amuse yourself with thinkin’ over what I’ve told you, and then go on with your descent.”

At this point Rooney’s heart almost failed him, but, catching sight of Maxwell’s half-amused, half-contemptuous face, he stepped resolutely on the ladder, and began to descend in haste.

“Hold on!” roared Baldwin, laying hold of the life-line. “Why, man alive, you’re off without the front-glass!”

“Och! Whirra! So I am,” said Rooney, pausing.

“Pump away, lads,” cried Baldwin, looking back at his assistants.

“Whist! What’s that?” asked the pupil excitedly, as a hissing sound buzzed round his head.

“Why, that’s the air coming in. Now then, I’ll screw on the glass. Are you all right?”

“All right,” replied Rooney, telling, as he said himself afterwards, “one of the biggist lies he iver towld in his life!”

The glass was screwed on, and the learner was effectually cut off from all connection with the outer air, save through the slight medium of an india-rubber pipe.

Having thus screwed him up—or in—Baldwin gave him the patronising pat on the helmet, as a signal for him to descend, but Rooney stood tightly fixed to the ladder, and motionless.

Again Baldwin patted his head encouragingly, but still Rooney stood as motionless as one of the iron-clad warriors in the Tower of London. The fact was, his courage had totally failed him. He was ashamed to come up, and could not by any effort of will force himself to go down.

“Why, what’s wrong?” demanded Baldwin, looking in at the glass, which, however, was so clouded with the inmate’s breath that he could only be seen dimly. It was evident that Rooney was speaking in an excited voice, but no sound was audible through that impervious mass of metal and glass. Baldwin was therefore about to unscrew the mouth-glass, when accident brought about what Rooney’s will could not accomplish. In attempting to move, the poor pupil missed his hold, or slipped somehow, and fell into the sea with a sounding splash.

“Let him go, boys—gently, or he’ll break everything. A dip’ll do him no harm,” cried Baldwin to the alarmed assistants.

The men let the life-line and air-tube slip, until the rushing descent was somewhat abated, and then, checking the involuntary diver, they hauled him slowly to the surface, where his arms and open palms went swaying wildly round until they came in contact with the ladder, on which they fastened with a grip that was sufficient to have squeezed the life out of a gorilla.

In a few seconds he ascended a step, and his head emerged, then another step, and Baldwin was able to unscrew the glass.

The first word that the poor man uttered through his porthole was “Och!” the next, “Musha!”

A burst of laughter from his friends above somewhat reassured him, and again the tinge of contempt in Maxwell’s voice reinfused courage and desperate resolve.

“Why, man, what was your haste?” said Baldwin.

“Sure the rounds o’ yer ladder was slippy,” answered Rooney, with some indignation. “Didn’t ye see, I lost me howld? Come, putt on the glass an’ I’ll try again. Never say die was a motto of me owld father, an’ it was the only legacy he left me.—I’m ready, sur.”

It is right here to remark that something of the pupil’s return of courage and resolution was due to his quick perception. He had time to reflect that he really had been at, or near, the bottom of the sea—at all events over head and ears in water—for several minutes without being drowned, even without being moistened, and his faith in the diving-dress, though still weak, had dawned sufficiently to assert itself as a power.

“Ha! My lad, you’ll do. You’ll make a diver yet,” said Baldwin, when about to readjust the glass. “I forgot to tell you that when your breath clouds the front-glass, you’ve only got to bend your head down, and wipe it off with your night-cap. Now, then, down you go once more.”

This time the pat on the head was followed by a descending motion. The mailed figure was feeling with its right foot for the next round of the ladder. Then slowly—very slowly—the left foot was let down, while the two hands held on with a tenacity that caused all the muscles and sinews to stand out rigidly. Then one hand was loosened, and caught nervously at a lower round—then the other hand followed, and thus by degrees the pupil went under the surface, when his helmet appeared like a large round ball of light enveloped in the milky-way of air-bubbles that rose from it.

“You’d better give the signal to ask if all’s right,” said Edgar, who felt a little anxious.

“Do so,” said Baldwin, nodding to the assistant.

The man obeyed, but no answering signal was returned.

According to rule they should instantly have hauled the diver up, but Baldwin bade them delay a moment.

“I’m quite sure there’s nothing wrong,” he said, stooping over the side of the barge, and gazing into the water, “it’s only another touch of nervousness.—Ah! I see him, holdin’ on like a barnacle to the ladder, afraid to let go. He’ll soon tire of kickin’ there—that’s it: there he goes down the rope like the best of us.”

In another moment the life-line and air-pipe ceased to run out, and then the assistant gave one pull on the line. Immediately there came back one pull—all right.

“That’s all right,” repeated Baldwin; “now the ice is fairly broken, and we’ll soon see how he’s going to get on.”

In order that we too may see that more comfortably, you and I, reader, will again go under water and watch him. We will also listen to him, for Rooney has a convenient habit of talking to himself, and neither water nor helmet can prevent us from overhearing.

True to his instructions, the pupil proceeded to fasten his clew-line to the stone at the foot of the ladder-rope, and attempted to kneel.

“Well, well,” he said, “did ye iver! What would me mother say if she heard I couldn’t git on my knees whin I tried to?”

Rooney began this remark aloud, but the sound of his own voice was so horribly loud and unnaturally near that he finished off in a whisper, and continued his observations in that confidential tone.

“Och! Is it dancin’ yer goin’ to do, Rooney?—in the day-time too!” he whispered, as his feet slowly left the bottom. “Howld on, man!”

He made a futile effort to stoop and grasp the mud, then, bethinking himself of Baldwin’s instructions, he remembered that too much air had a tendency to bring him to the surface, and that opening the front-valve was the remedy. He was not much too soon in recollecting this, for, besides rising, he was beginning to feel a singing in his head and a disagreeable pressure on the ears, caused by the ever-increasing density of the air. The moment the valve was fully opened, a rush out of air occurred which immediately sank him again, and he had now no difficulty in getting on his knees.

“There’s little enough light down here, anyhow,” he muttered, as he fumbled about the stone sinker in a vain attempt to fasten his line to it, “sure the windy must be dirty.”

The thought reminded him of Baldwin’s teaching. He bent forward his head and wiped the glass with his night-cap, but without much advantage, for the dimness was caused by the muddiness of the water.

Just then he began to experience uncomfortable sensations; he felt a tendency to gasp for air, and became very hot, while his garments clasped his limbs very tightly. He had, like Maxwell, forgotten to reclose the breast-valve, but, unlike the more experienced diver, he had failed to discover his omission. He became flurried and anxious, and getting, more and more confused, fumbled nervously at his helmet to ascertain that all was right there. In so doing he opened the little regulating cock, which served to form an additional outlet to foul air. This of course made matters worse. The pressure of air in the dress was barely sufficient to prevent the water from entering by the breast-valve and regulating cock. Perspiration burst out on his forehead. He naturally raised his hand to wipe it away, but was prevented by the helmet.

Rooney possessed an active mind. His thoughts flew fast. This check induced the following ideas—

“What if I shud want to scratch me head or blow me nose? Or what if an earwig shud chance to have got inside this iron pot, and take a fancy to go into my ear?”

His right ear became itchy at the bare idea. He made a desperate blow at it, and skinned his knuckles, while a hitherto unconceived intensity of desire to scratch his head and blow his nose took violent possession of him.

Just then a dead cat, that had been flung into the harbour the night before, and had not been immersed long enough to rise to the surface, floated past with the tide, and its sightless eyeballs and ghastly row of teeth glared and glistened on him, as it surged against his front-glass. A slight spirt of water came through the regulating cock at the same instant, as if the dead cat had spit in his face.

“Hooroo! Haul up!” shouted Rooney, following the order with a yell that sounded like the concentrated voice of infuriated Ireland. At the same time he seized the life-line and air-tube, and tugged at both, not four times, but nigh forty times four, and never ceased to tug until he found himself gasping on the deck of the barge with his helmet off and his comrades laughing round him.

“It’s not a bad beginning,” said Baldwin, as he assisted his pupil to unrobe; “you’ll make a good diver in course o’ time.”

Baldwin was right in this prophecy, for in a few months Rooney Machowl became one of the best and coolest divers on his staff.

We need not try the reader’s patience with an account of Edgar’s descent, which immediately followed that of the Irishman. Let it suffice to say that he too accomplished, with credit and with less demonstration, his first descent to the bottom of the sea.

Chapter Three.

Refers to a small Tea-Party, and touches very mildly on Love.

Miss Pritty was a good soul, but weak. She was Edgar Berrington’s maiden aunt—of an uncertain age—on the mother’s side. Her chief characteristic was delicacy—delicacy of health, delicacy of sentiment, delicacy of intellect—general delicacy, in fact, all over. She was slight too—slightly made, slightly educated, slightly pretty, and slightly cracked. But there were a few things in regard to which Miss Laura Pritty was strong. She was strong in her affections, strong in her reverence for all good things (including a few bad things which in her innocence she thought good), strong in her prejudices and impulses, and strong—remarkably strong—in parentheses. Her speech was eminently parenthetical, insomuch that the range of her ideas was wholly untrammelled by the proprieties of subject or language. Given a point to be aimed at in conversation, Miss Pritty never aimed at it. She invariably began with it, and, parting finally from it at the outset, diverged to any or every other point in nature. Perplexity, as a matter of course, was the usual result both in speaker and hearer, but then that mattered little, for Miss Pritty was also strong in easy-going good-nature.

On the evening in which we introduce her, Miss Pritty was going to have her dear and intimate friend Aileen Hazlit to tea, and she laid out her little tea-table with as much care as an engineer might have taken in drawing a mathematical problem. The teapot was placed in the exact centre of the tray, with its spout and handle pointing so that a line drawn through them would have been parallel to the sides of her little “boudoir.” The urn stood exactly behind it. The sugar-basin formed, on one side of the tray, a pendant to the cream-jug on the other, and inasmuch as the cream-jug was small, a toast-rack was coupled with it to constitute the necessary balance. So, too, with the cups: they were placed equidistant from the teapot, the sides of the tray, and each other, while a salver of cake on one side of the table was scrupulously balanced by a plate of buns on the other side.

“There she is—the darling!” exclaimed Miss Pritty, with a little skip and (excuse the word) a giggle as the bell rang.

“Miss Aileen Hazlit,” announced Miss Pritty’s small and only domestic, who flung wide open the door of the boudoir, as its owner was fond of styling it.

Whereupon there entered “an angel in blue, with a straw hat and ostrich feather.”

We quote from the last, almost dying, speech of a hopeless youth in the town—a lawyer’s clerk—whose heart was stamped over so completely with the word “Aileen” that it was unrecognisable, and practically useless for any purpose except beating—which it did, hard, at all times.

Aileen was beautiful beyond compare, because, in her case, extreme beauty of face and feature was coupled with rare beauty of expression, indicating fine qualities of mind. She was quiet in demeanour, grave in speech, serious and very earnest in thought, enthusiastic in action, unconscious and unselfish.

“Pooh! Perfection!” I hear some lady reader ejaculate.

No, fair one, not quite that, but as near it as was compatible with humanity. Happily there are many such in the world—some with more and some with less of the external beauty—and man is blessed and the world upheld by them.

The chief bond that bound Aileen and Miss Pritty together was a text of Scripture, “Consider the poor.” The latter had strong sympathy with the poor, being herself one of the number. The former, being rich in faith as well as in means, “considered” them. The two laid their heads together and concerted plans for the “raising of the masses,” which might have been food for study to some statesmen. For instance, they fed the hungry and clothed the naked; they encouraged the well-disposed and reproved the evil; they “scattered seeds of kindness” wherever they went; they sowed the precious Word of God in all kinds of ground—good and bad; they comforted the sorrowing; they visited the sick and the prisoner; they refused to help, or, in any way to encourage, the idle; they handed the obstreperous and violent over to the police, with the hope—if not the recommendation—that the rod should not be spared; and in all cases they prayed for them. The results were considerable, but, not being ostentatiously trumpeted, were not always recognised or traced to their true cause.

“Come away, darling,” exclaimed Miss Pritty, eagerly embracing and kissing her friend, who accepted, but did not return, the embrace, though she did the kiss. “I thought you were not coming at all, and I have not seen you for a whole week! What has kept you? There, put off your hat. I’m so glad to see you, dear Aileen. Isn’t it strange that I’m so fond of you? They say that people who are contrasts generally draw together—at least I’ve often heard Mrs Boxer, the wife of Captain Boxer, you know, of the navy, who used to swear so dreadfully before he was married, but, I am happy to say, has quite given it up now, which says a great deal for wedded life, though it’s a state that I don’t quite believe in myself, for if Adam had never married Eve he would not have been tempted to eat the forbidden fruit, and so there would have been no sin and no sorrow or poverty—no poor! Only think of that.”

“So that our chief occupation would have been gone,” said Aileen, with a slight twinkle of her lustrous blue eyes, “and perhaps you and I might never have met.”

Miss Pritty replied to this something very much to the effect that she would have preferred the entrance of sin and all its consequences—poverty included—into the world, rather than have missed making the friendship of Miss Hazlit. At least her words might have borne that interpretation—or any other!

“My father detained me,” said Aileen, seating herself at the table, while her volatile friend put lumps of sugar into the cups, with a tender yet sprightly motion of the hand, as if she were doing the cups a special kindness—as indeed she was, when preparing one of them to touch the lips of Aileen.

“Naughty man, why did he detain you?” said Miss Pritty.

“Only to write one or two notes, his right hand being disabled at present by rheumatism.”

“A gentleman, Miss, in the dinin’-room,” said the small domestic, suddenly opening a chink of the door for the admission of her somewhat dishevelled head. “He won’t send his name up—says he wants to see you.”

“How vexing!” exclaimed Miss Pritty, “but I’ll go down. I’m determined that he shan’t interrupt our tête-à-tête.”

Miss Pritty uttered a little scream of surprise on entering the dining-room.

“Well, aunt,” said Edgar Berrington, with a hearty smile, as he extended his hand, “you are surprised to see me?”

“Of course I am, dear Eddy,” cried Miss Pritty, holding up her cheek for a kiss. “Sit down. Why, you were in London when I last heard of you.”

“True, but I’m not in London now, as you see. I’ve been a week here.”

“A week, Eddy! And you did not come to see me till now?”

“Well, I ought to apologise,” replied the youth, with a slight look of confusion, “but—the fact is, I came down partly on business, and—and—so you see I’ve been very busy.”

“Of course,” laughed Miss Pritty; “people who have business to do are usually very busy! Well, I forgive you, and am glad to see you—but—”

“Well, aunt—but what?”

“In short, Eddy, I happen to be particularly engaged this evening—on business, too, like yourself; but, after all, why should I not introduce you to my friend? You might help us in our discussion—it is to be about the poor. Do you know much about the poor and their miseries?”

Edgar smiled sadly as he replied—

“Yes, I have had some experimental knowledge of the poor—being one of them myself, and my poverty too has made me inconceivably miserable.”

“Come, Eddy, don’t talk nonsense. You know I mean the very poor, the destitute. But let us go up-stairs and have a cup of tea.”

The idea of discussing the condition of the poor over a cup of tea with two ladies was not attractive to our hero in his then state of mind, and he was beginning to excuse himself when his aunt stopped him:—

“Now, don’t say you can’t, or won’t, for you must. And I shall introduce you to a very pretty girl—oh! such a pretty one—you’ve no idea—and so sweet!”

Miss Pritty spoke impressively and with enthusiasm, but as the youth knew himself to be already acquainted with and beloved by the prettiest girl in the town he was not so much impressed as he might have been. However, being a good-natured fellow, he was easily persuaded.

All the way up-stairs, and while they were entering the boudoir, little Miss Pritty’s tongue never ceased to vibrate, but when she observed her nephew gazing in surprise at her friend, whose usually calm and self-possessed face was covered with confusion, she stopped suddenly.

“Good-evening, Miss Hazlit,” said Edgar, recovering himself, and holding out his hand as he advanced towards her; “I did not anticipate the pleasure of meeting you here.”

“Then you are acquainted already!” exclaimed Miss Pritty, looking as much amazed as if the accident of two young people being acquainted without her knowledge were something tantamount to a miracle.

“Yes, I have met Mr Berrington at my father’s several times,” said Aileen, resuming her seat, and bestowing a minute examination on the corner of her handkerchief.

If Aileen had added that she had met Mr Berrington every evening for a week past at her father’s, had there renewed the acquaintance begun in London a year before, and had been wooed and won by him before his stern repulse by her father, she would have said nothing beyond the bare truth; but she thought, no doubt, that it was not necessary to add all that.

“Well, well, what strange things do happen!” said Miss Pritty, resuming her duties at the tea-table. “Sugar, Eddy? And cream?—Only to think that Aileen and I have known each other so well, and she did not know that you were my nephew; but after all it could not well be otherwise, for now I think of it, I never mentioned your name to her. Out of sight, out of mind, Eddy, you know, and indeed you don’t deserve to be remembered. If we all had our deserts, some people that I know of would be in a very different position from what they are, and some people wouldn’t be at all.”

“Why, aunt,” said Edgar, laughing. “Would you—”

“Some more cake, Eddy?”

“No, thank you. I was going to say—”

“Have you enough cream? Allow me to—”

“Quite enough, thanks. I was about to remark—”

“Some sugar, Aileen?—I beg your pardon—yes—you were about to say—”

“Oh! Nothing,” replied Edgar, half exasperated by these frequent interruptions, but laughing in spite of himself, “only I’m surprised that sentence of annihilation should be passed on ‘some people’ by one so amiable as you are.”

“Oh! I didn’t exactly mean annihilation,” returned Miss Pritty, with a pitiful smile; “I only mean that I wouldn’t have had them come into existence, they seem to be so utterly useless in the world, and so interfering, too, with those who want to be useful.”

“Surely that quality, or capacity of interference, proves them to be not utterly useless,” said Edgar, “for does it not give occasion for the exercise of patience and forbearance?”

“Ah!” replied Miss Pritty, with an arch smile, shaking her finger at her nephew, “you are a fallacious reasoner. Do you know what that means? I can’t help laughing still at the trouble I used to have in trying to find out the meaning of that word fallacious, when I was at Miss Dullandoor’s seminary for young ladies—hi! Hi! Some of us were excessively young ladies, and we were taught everything by rote, explanations of meanings of anything being quite ignored by Miss Dullandoor. Do you remember her sister? Oh! I’m so stupid to forget that it’s exactly thirty years to-day since she died, and you can’t be quite that age yet; besides, even if you were, it would require that you should have seen, and recognised, and remembered her on her deathbed about the time of your own birth. Oh! She was so funny, both in face and figure. One of the older girls made a portrait of her for me which I have yet. I’ll go fetch it; the expression is irresistible—it is killing. Excuse me a minute.”

Miss Pritty rose and tripped—she never walked—from the room. During much of the previous conversation our hero had been sorely perplexed in his mind as to his duty in present circumstances. Having been forbidden to hold any intercourse with Aileen, he questioned the propriety of his remaining to spend the evening with her, and had made up his mind to rise and tear himself away when this unlooked-for opportunity for a tête-à-tête occurred. Being a man of quick wit and strong will, he did not neglect it. Turning suddenly to the fair girl, he said, in a voice low and measured—

“Aileen, your father commanded me to have no further intercourse with you, and he made me aware that he had laid a similar injunction on yourself. I know full well your true-hearted loyalty to him, and do not intend to induce you to disobey. I ask you to make no reply to what I say that is not consistent with your promise to your father. For myself, common courtesy tells me that I may not leave your presence for a distant land without saying at least good-bye. Nay, more, I feel that I break no command in making to you a simple deliberate statement.”

Edgar paused for a moment, for, in spite of the powerful restraint put on himself, and the intended sedateness of his words, his feelings were almost too strong for him.

“Aileen,” he resumed, “I may never see you again. Your father intends that I shall not. Your looks seem to say that you fear as much. Now, my heart tells me that I shall; but, whatever betide, or wherever I go, let me assure you that I will continue to love you with unalterable fidelity. More than this I shall not say, less I could not. You said that these New Testaments”—pointing to a pile of four or five which lay on the table—“are meant to be given to poor men. I am a poor man: will you give me one?”

“Willingly,” said Aileen, taking one from the pile.

She handed it to her lover without a single word, but with a tender anxious look that went straight to his heart, and took up its lodging there—to abide for ever!

The youth grasped the book and the hand at once, and, stooping, pressed the latter fervently to his lips.

At that moment Miss Pritty was heard tripping along the passage.

Edgar sprang to intercept her, and closed the door of the boudoir behind him.

“Why, Edgar, you seem in haste!”

“I am, dear aunt; circumstances require that I should be. Come down-stairs with me. I have stayed too long already. I am going abroad, and may not spend more time with you this evening.”

“Going abroad!” exclaimed Miss Pritty, in breathless surprise, “where?”

“I don’t know. To China, Japan, New Zealand, the North Pole—anywhere. In fact, I’ve not quite fixed. Good-bye, dear aunt. Sorry to have seen so little of you. Good-bye.”

He stooped, printed a gentle kiss between Miss Pritty’s wondering eyes, and vanished.

“A most remarkable boy,” said the disconcerted lady, resuming her seat at the tea-table—“so impulsive and volatile. But he’s a dear good boy nevertheless—was so kind to his mother while she was alive, and ran away from school when quite young—and no wonder, for it was a dreadful school, where they used to torture the boys,—absolutely tortured them. The head-master and ushers were tried for it afterwards, I’m told. At all events; Eddy ran away from it after pulling the master’s nose and kicking the head usher—so it is said, though I cannot believe it, he is usually so gentle and courteous.—Do have a little more tea. No? A piece of bun? No? Why, you seem quite flushed, my love. Not unwell, I trust? No? Well, then, let us proceed to business.”

Chapter Four.

Divers Matters.

Charles Hazlit, Esquire, was a merchant and a shipowner, a landed proprietor, a manager of banks, a member of numerous boards and committees, a guardian of the poor, a volunteer colonel, and a good-humoured man on the whole, but purse-proud and pompous. He was also the father of Aileen.

Behold him seated in an elegant drawing-room, in a splendid mansion at the “west end” (strange that all aristocratic ends would appear to be west ends!) of the seaport town which owned him. His blooming daughter sat beside him at a table, on which lay a small, peculiar, box. He doated on his daughter, and with good reason. Their attention was so exclusively taken up with the peculiar box that they had failed to observe the entrance, unannounced, of a man of rough exterior, who stood at the door, hat in hand, bowing and coughing attractively, but without success.

“My darling,” said Mr Hazlit, stooping to kiss his child—his only child—who raised her pretty little three-cornered mouth to receive it, “this being your twenty-first birthday, I have at last brought myself to look once again on your sainted mother’s jewel-case, in order that I may present it to you. I have not opened it since the day she died. It is now yours, my child.”

Aileen opened her eyes in mute amazement. It would seem as though there had been some secret sympathy between her and the man at the door, for he did precisely the same thing. He also crushed his hat somewhat convulsively with both hands, but without doing it any damage, as it was a very hard sailor-like hat. He also did something to his lips with his tongue, which looked a little like licking them.

“Oh papa!” exclaimed Aileen, seizing his hand, “how kind; how—”

“Nay, love, no thanks are due to me. It is your mother’s gift. On her deathbed she made me promise to give it you when you came of age, and to train you, up to that age, as far as possible, with a disregard for dress and show. I think your dear mother was wrong,” continued Mr Hazlit, with a mournful smile, “but, whether right or wrong, you can bear me witness that I have sought to fulfil the second part of her dying request, and I now accomplish the first.”

He proceeded to unlock, the fastenings of the little box, which was made of some dark metal resembling iron, and was deeply as well as richly embossed on the lid and sides with quaint figures and devices.

Mr Hazlit had acquired a grand, free-handed way of manipulating treasure. Instead of lifting the magnificent jewels carefully from the casket, he tumbled them out like a gorgeous cataract of light and colour, by the simple process of turning the box upside down.

“Oh papa, take care!” exclaimed Aileen, spreading her little hands in front of the cataract to stem its progress to the floor, while her two eyes opened in surprise, and shone with a lustre that might have made the insensate gems envious. “How exquisite! How inexpressibly beautiful!—oh my dear, darling mother—!”

She stopped abruptly, and tears fluttered from her eyes. In a few seconds she continued, pushing the gems away, almost passionately—

“But I cannot wear them, papa. They are worthless to me.”

She was right. She had no need of such gems. Was not her hair golden and her skin alabaster? Were not her lips coral and her teeth pearls? And were not diamonds of the purest water dropping at that moment from her down-cast eyes?

“True, my child, and the sentiment does your heart credit; they are worthless, utterly worthless— mere paste”—at this point the face of the man at the door visibly changed for the worse—“mere paste, as regards their power to bring back to us the dear one who wore them. Nevertheless, in a commercial point of view”—here the ears of the man at the door cocked—“they are worth some eight or nine thousand pounds sterling, so they may as well be taken care of.”

The tongue and lips of the man at the door again became active. He attempted—unsuccessfully, as before—to crush his hat, and inadvertently coughed.

Mr Hazlit’s usually pale countenance flushed, and he started up.

“Hallo! My man, how came you here?”

The man looked at the door and hesitated in his attempt to reply to so useless a question.

“How comes it that you enter my house and drawing-room without being announced?” asked Mr Hazlit, drawing himself up.

“’Cause I wanted to see you, an’ I found the door open, an’ there warn’t nobody down stair to announce me,” answered the man in a rather surly tone.

“Oh, indeed?—ah,” said Mr Hazlit, drawing out a large silk handkerchief with a flourish, blowing his nose therewith, and casting it carelessly on the table so as to cover the jewel-box. “Well, as you are now ere, pray what have you got to say to me?”

“Your ship the Seagull has bin’ wrecked, sir, on Toosday night on the coast of Wales.”

“I received that unpleasant piece of news on Wednesday morning. What has that to do with your visit?”

“Only that I thought you might want divers for to go to the wreck, an’ I’m a diver—that’s all.”

The man at the door said this in a very surly tone, for the slight tendency to politeness which had begun to manifest itself while the prospect of “a job” was hopeful, vanished before the haughty manner of the merchant.

“Well, it is just possible that I may require the assistance of divers,” said Mr Hazlit, ringing the bell; “when I do, I can send for you.—John, show this person out.”

The hall-footman, who had been listening attentively at the key-hole, and allowed a second or two to elapse before opening the door, bowed with a guilty flush on his face and held the door wide open.

David Maxwell—for it was he—passed out with an angry scowl, and as he strode with noisy tread across the hall, said something uncommonly pithy to the footman about “upstarts” and “puppies,” and “people who thought they was made o’ different dirt from others,” accompanied with many other words and expressions which we may not repeat.

To all of this John replied with bland smiles and polite bows, hoping that the effects of the interview might not render him feverish, and reminding him that if it did he was in a better position than most men for cooling himself at the bottom of the sea.

“Farewell,” said John earnestly; “and if you should take a fancy to honour us any day with your company to dinner, do send a line to say you’re coming.”

John did not indulge in this pleasantry until the exasperated diver was just outside of the house, and it was well that he was so prudent, for Maxwell turned round like a tiger and struck with tremendous force at his face. His hard knuckles met the panel of the door, in which they left an indelible print, and at the same time sent a sound like a distant cannon shot into the library.

“I’m afraid I have been a little too sharp with him,” said Mr Hazlit, assisting his daughter to replace the jewels.

Aileen agreed with him, but as nothing could induce her to condemn her father with her lips she made no reply.

“But,” continued the old gentleman, “the rascal had no right to enter my house without ringing. He might have been a thief, you know. He looked rough and coarse enough to be one.”

“Oh papa,” said Aileen entreatingly, “don’t be too hasty in judging those who are sometimes called rough and coarse. I do assure you I’ve met many men in my district who are big and rough and coarse to look at, but who have the feelings and hearts of tender women.”

“I know it, simple one; you must not suppose that I judged him by his exterior; I judged him by his rude manner and conduct, and I do not extend my opinion of him to the whole class to which he belongs.”

It is strange—and illustrative of the occasional perversity of human reasoning—that Mr Hazlit did not perceive that he himself had given the diver cause to judge him, Mr Hazlit, very harshly, and the worst of it was that Maxwell did, in his wrath, extend his opinion of the merchant to the entire class to which he belonged, expressing a deep undertoned hope that the “whole bilin’ of ’em” might end their days in a place where he spent many of his own, namely, at the bottom of the sea. It is to be presumed that he wished them to be there without the benefit of diving-dresses!

“It is curious, however,” continued Mr Hazlit, “that I had been thinking this very morning about making inquiries after a diver, one whom I have frequently heard spoken of as an exceedingly able and respectable man—Balding or Bolding or some such name, I think.”

“Oh! Baldwin, Joe Baldwin, as his intimate friends call him,” said Aileen eagerly. “I know him well; he is in my district.”

“What!” exclaimed Mr Hazlit, “not one of your paupers?”

Aileen burst into a merry laugh. “No, papa, no; not a pauper certainly. He’s a well-off diver, and a Wesleyan—a local preacher, I believe—but he lives in my district, and is one of the most zealous labourers in it. Oh! If you saw him, papa, with his large burly frame and his rough bronzed kindly face, and broad shoulders, and deep bass voice and hearty laugh.”

The word suggested the act, for Aileen went off again at the bare idea of Joe Baldwin being a pauper—one at whose feet, she said, she delighted to sit and learn.

“Well, I’m glad to have such a good account of him from one so well able to judge,” rejoined her father, “and as I mean to go visit him without delay I’ll be obliged if you’ll give me his address.”

Having received it, the merchant sallied forth into those regions of the town where, albeit she was not a guardian of the poor, his daughter’s light figure was a much more familiar object than his own.

“Does a diver named Baldwin live here?” asked Mr Hazlit of a figure which he found standing in a doorway near the end of a narrow passage.

The figure was hazy and indistinct by reason of the heavy wreaths of tobacco-smoke wherewith it was enveloped.

“Yis, sur,” replied the figure; “he lives in the door it the other ind o’ the passage. It’s not over-light here, sur; mind yer feet as ye go, an’ pay attintion to your head, for what betune holes in the floor an’ beams in the ceilin’, tall gintlemen like you, sur, come to grief sometimes.”

Thanking the figure for its civility, Mr Hazlit knocked at the door indicated, but there was no response.

“Sure it’s out they are!” cried the figure from the other end of the passage. “Joe Baldwin’s layin’ a charge under the wreck off the jetty to-day—no doubt that’s what’s kep’ ’im, and it’s washin’-day with Mrs Joe, I belave; but I’m his pardner, sur, an’ if ye’ll step this way, Mrs Machowl’ll be only too glad to see ye, sur, an’ I can take yer orders.”