« back

With Frederick The Great:

A Story of the Seven Years' War

by G. A. Henty.

Illustrated by Wal Paget

1910

| Preface. | |

| Chapter 1: | King and Marshal. |

| Chapter 2: | Joining. |

| Chapter 3: | The Outbreak Of War. |

| Chapter 4: | Promotion. |

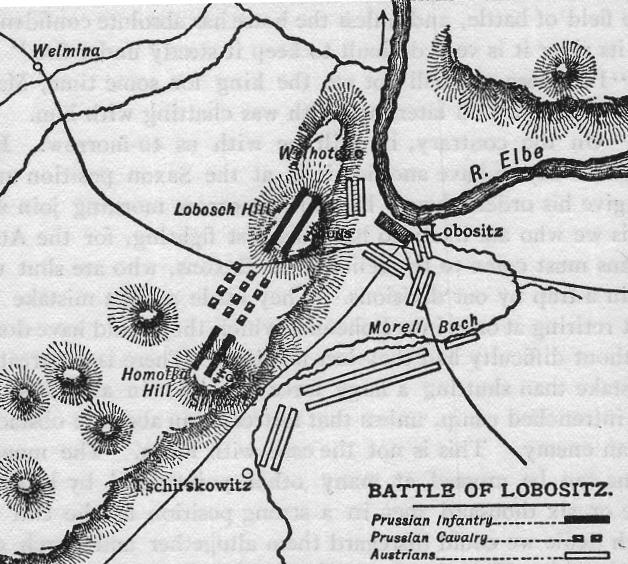

| Chapter 5: | Lobositz. |

| Chapter 6: | A Prisoner. |

| Chapter 7: | Flight. |

| Chapter 8: | Prague. |

| Chapter 9: | In Disguise. |

| Chapter 10: | Rossbach. |

| Chapter 11: | Leuthen. |

| Chapter 12: | Another Step. |

| Chapter 13: | Hochkirch. |

| Chapter 14: | Breaking Prison. |

| Chapter 15: | Escaped. |

| Chapter 16: | At Minden. |

| Chapter 17: | Unexpected News. |

| Chapter 18: | Engaged. |

| Chapter 19: | Liegnitz. |

| Chapter 20: | Torgau. |

| Chapter 21: | Home. |

| Map showing battlefields of the Seven Years' War |

| Battle of Lobositz |

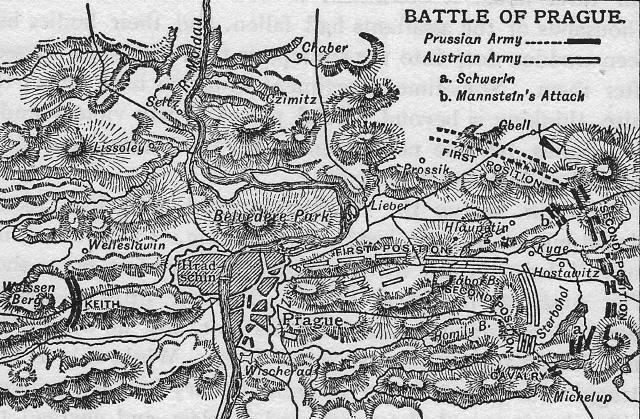

| Battle of Prague |

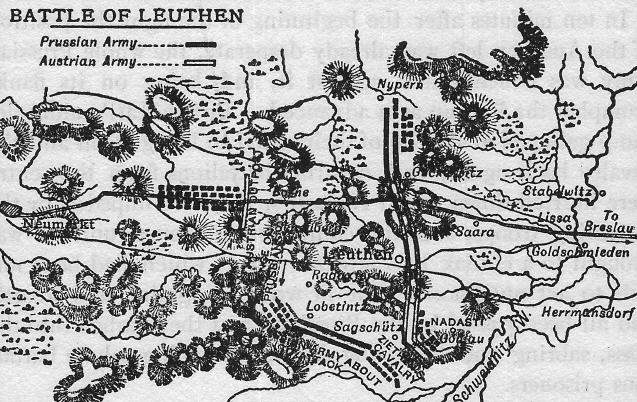

| Battle of Leuthen |

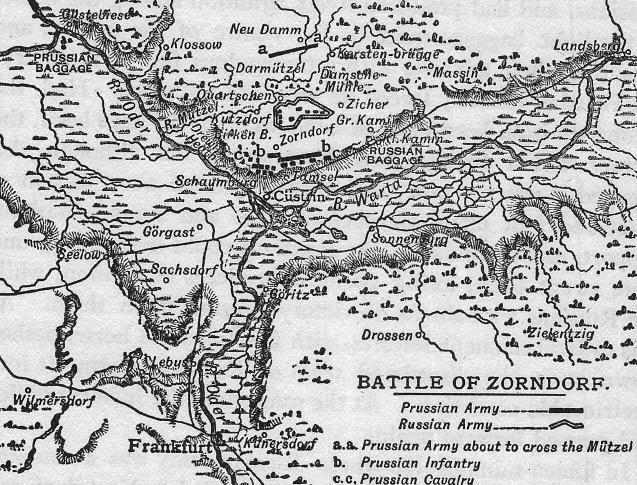

| Battle of Zorndorf |

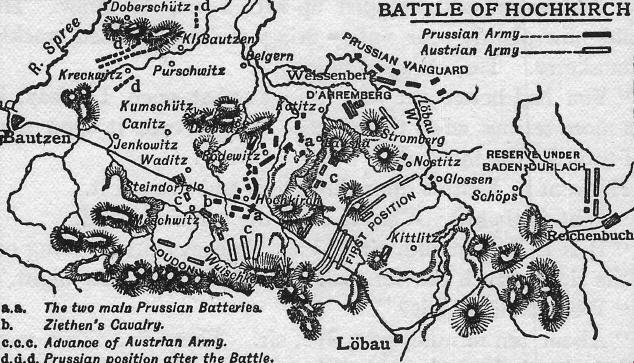

| Battle of Hochkirch |

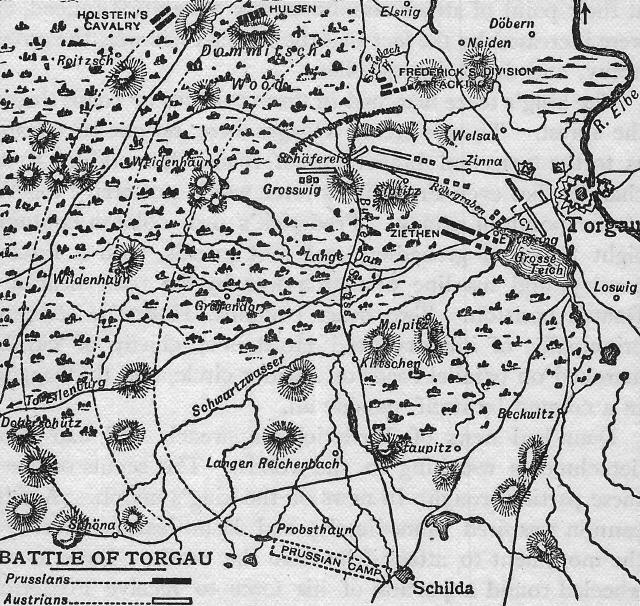

| Battle of Torgau |

Preface.

Among the great wars of history there are few, if any, instances of so long and successfully sustained a struggle, against enormous odds, as that of the Seven Years' War, maintained by Prussia--then a small and comparatively insignificant kingdom--against Russia, Austria, and France simultaneously, who were aided also by the forces of most of the minor principalities of Germany. The population of Prussia was not more than five millions, while that of the Allies considerably exceeded a hundred millions. Prussia could put, with the greatest efforts, but a hundred and fifty thousand men into the field, and as these were exhausted she had but small reserves to draw upon; while the Allies could, with comparatively little difficulty, put five hundred thousand men into the field, and replenish them as there was occasion. That the struggle was successfully carried on, for seven years, was due chiefly to the military genius of the king; to his indomitable perseverance; and to a resolution that no disaster could shake, no situation, although apparently hopeless, appall. Something was due also, at the commencement of the war, to the splendid discipline of the Prussian army at that time; but as comparatively few of those who fought at Lobositz could have stood in the ranks at Torgau, the quickness of the Prussian people to acquire military discipline must have been great; and this was aided by the perfect confidence they felt in their king, and the enthusiasm with which he inspired them.

Although it was not, nominally, a war for religion, the consequences were as great and important as those which arose from the Thirty Years' War. Had Prussia been crushed and divided, Protestantism would have disappeared in Germany, and the whole course of subsequent events would have been changed. The war was scarcely less important to Britain than to Prussia. Our close connection with Hanover brought us into the fray; and the weakening of France, by her efforts against Prussia, enabled us to wrest Canada from her, to crush her rising power in India, and to obtain that absolute supremacy at sea that we have never, since, lost. And yet, while every school boy knows of the battles of ancient Greece, not one in a hundred has any knowledge whatever of the momentous struggle in Germany, or has ever as much as heard the names of the memorable battles of Rossbach, Leuthen, Prague, Zorndorf, Hochkirch, and Torgau. Carlyle's great work has done much to familiarize older readers with the story; but its bulk, its fullness of detail, and still more the peculiarity of Carlyle's diction and style, place it altogether out of the category of books that can be read and enjoyed by boys.

I have therefore endeavoured to give the outlines of the struggle, for their benefit; but regret that, in a story so full of great events, I have necessarily been obliged to devote a smaller share than usual to the doings of my hero.

G. A. Henty.

Chapter 1: King and Marshal.

It was early in 1756 that a Scottish trader, from Edinburgh, entered the port of Stettin. Among the few passengers was a tall young Scotch lad, Fergus Drummond by name. Though scarcely sixteen, he stood five feet ten in height; and it was evident, from his broad shoulders and sinewy appearance, that his strength was in full proportion to his height. His father had fallen at Culloden, ten years before. The glens had been harried by Cumberland's soldiers, and the estates confiscated. His mother had fled with him to the hills; and had lived there, for some years, in the cottage of a faithful clansman, whose wife had been her nurse. Fortunately, they were sufficiently well off to be able to maintain their guests in comfort; and indeed the presents of game, fish, and other matters, frequently sent in by other members of the clan, had enabled her to feel that her maintenance was no great burden on her faithful friends.

For some years, she devoted herself to her son's education; and then, through the influence of friends at court, she obtained the grant of a small portion of her late husband's estates; and was able to live in comfort, in a position more suited to her former rank.

Fergus' life had been passed almost entirely in the open air. Accompanied by one or two companions, sons of the clansmen, he would start soon after daybreak and not return until sunset, when they would often bring back a deer from the forests, or a heavy creel of salmon or trout from the streams. His mother encouraged him in these excursions, and also in the practice of arms. She confined her lessons to the evening, and even after she settled on her recovered farm of Kilgowrie, and obtained the services of a tutor for him, she arranged that he should still be permitted to pass the greater part of the day according to his own devices.

She herself was a cousin of the two brothers Keith; the one of whom, then Lord Marischal, had proclaimed the Old Pretender king at Edinburgh; and both of whom had attained very high rank abroad, the younger Keith having served with great distinction in the Spanish and Russian armies, and had then taken service under Frederick the Great, from whom he had received the rank of field marshal, and was the king's greatest counsellor and friend. His brother had joined him there, and stood equally high in the king's favour. Although both were devoted Jacobites, and had risked all, at the first rising in favour of the Old Pretender, neither had taken part in that of Charles Edward, seeing that it was doomed to failure. After Culloden, James Keith, the field marshal, had written to his cousin, Mrs. Drummond, as follows:

"Dear Cousin,

"I have heard with grief from Alexander Grahame, who has come over here to escape the troubles, of the grievous loss that has befallen you. He tells me that, when in hiding among the mountains, he learned that you had, with your boy, taken refuge with Ian the forester, whom I well remember when I was last staying with your good husband, Sir John. He also said that your estates had been confiscated, but that he was sure you would be well cared for by your clansmen. Grahame told me that he stayed with you for a few hours, while he was flying from Cumberland's bloodhounds; and that you told him you intended to remain there, and to devote yourself to the boy's education, until better times came.

"I doubt not that ere long, when the hot blood that has been stirred up by this rising has cooled down somewhat, milder measures will be used, and some mercy be shown; but it may be long, for the Hanoverian has been badly frightened, and the Whigs throughout the country greatly scared, and this for the second time. I am no lover of the usurper, but I cannot agree with all that has been said about the severity of the punishment that has been dealt out. I have been fighting all over Europe, and I know of no country where a heavy reckoning would not have been made, after so serious an insurrection. Men who take up arms against a king know that they are staking their lives; but after vengeance comes pardon, and the desire to heal wounds, and I trust that you will get some portion of your estate again.

"It is early yet to think of what you are going to make of the boy, but I am sure you will not want to see him fighting in the Hanoverian uniform. So, if he has a taste for adventure let him, when the time comes, make his way out to me; or if I should be under the sod by that time, let him go to my brother. There will, methinks, be no difficulty in finding out where we are, for there are so many Scotch abroad that news of us must often come home. However, from time to time I will write to you. Do not expect to hear too often, for I spend far more time in the saddle than at my table, and my fingers are more accustomed to grasp a sword than a pen. However, be sure that wherever I may be, I shall be glad to see your son, and to do my best for him.

"See that he is not brought up at your apron string, but is well trained in all exercises; for we Scots have gained a great name for strength and muscle, and I would not that one of my kin should fall short of the mark."

Maggie Drummond had been much pleased with her kinsman's letter. There were few Scotchmen who stood higher in the regard of their countrymen, and the two Keiths had also a European reputation. Her husband, and many other fiery spirits, had expressed surprise and even indignation that the brothers, who had taken so prominent a part in the first rising, should not have hastened to join Prince Charlie; but the more thoughtful men felt it was a bad omen that they did not do so. It was certainly not from any want of adventurous spirit, or of courage, for wherever adventures were to be obtained, wherever blows were most plentiful, James Keith and his brother were certain to be in the midst of them.

But Maggie Drummond knew the reason for their holding aloof; for she had, shortly before the coming over of Prince Charlie, received a short note from the field marshal:

"They say that Prince Charles Edward is meditating a mad scheme of crossing to Scotland, and raising his standard there. If so, do what you can to prevent your husband from joining him. We made but a poor hand of it, last time; and the chances of success are vastly smaller now. Then it was but a comparatively short time since the Stuarts had lost the throne of England, and there were great numbers who wished them back. Now the Hanoverian is very much more firmly seated on the throne. The present man has a considerable army, and the troops have had experience of war on the Continent, and have shown themselves rare soldiers. Were not my brother Lord Marischal of Scotland, and my name somewhat widely known, I should not hang back from the adventure, however desperate; but our example might lead many who might otherwise stand aloof to take up arms, which would bring, I think, sure destruction upon them. Therefore we shall restrain our own inclinations, and shall watch what I feel sure will be a terrible tragedy, from a distance; striking perhaps somewhat heavier blows than usual upon the heads of Turks, Moors, Frenchmen, and others, to make up for our not being able to use our swords where our inclinations would lead us.

"The King of France will assuredly give no efficient aid to the Stuarts. He has all along used them as puppets, by whose means he can, when he chooses, annoy or coerce England. But I have no belief that he will render any useful aid, either now or hereafter.

"Use then, cousin, all your influence to keep Drummond at home. Knowing him as I do, I have no great hope that it will avail; for I know that he is Jacobite to the backbone, and that, if the Prince lands, he will be one of the first to join him."

Maggie had not carried out Keith's injunction. She had indeed told her husband, when she received the letter, that Keith believed the enterprise to be so hopeless a one that he should not join in it. But she was as ardent in the cause of the Stuarts as was her husband, and said no single word to deter him when, an hour after he heard the news of the prince's landing, he mounted and rode off to meet him, and to assure him that he would bring every man of his following to the spot where his adherents were to assemble. From time to time his widow had continued to write to Keith; though, owing to his being continually engaged on campaigns against the Turks and Tartars, he received but two or three of her letters, so long as he remained in the service of Russia. When, however, he displeased the Empress Elizabeth, and at once left the service and entered that of Prussia, her letters again reached him.

The connection between France and Scotland had always been close, and French was a language familiar to most of the upper class; and since the civil troubles began, such numbers of Scottish gentlemen were forced either to shelter in France, or to take service in the French or other foreign armies, that a knowledge of the language became almost a matter of necessity. In one of his short letters Keith had told her that, of all things, it was necessary that the lad should speak French with perfect fluency, and master as much German as possible. And it was to these points that his education had been almost entirely directed.

As to French there was no difficulty and, when she recovered a portion of the estate, Maggie Drummond was lucky in hearing of a Hanoverian trooper who, having been wounded and left behind in Glasgow, his term of service having expired, had on his recovery married the daughter of the woman who had nursed him. He was earning a somewhat precarious living by giving lessons in the use of the rapier, and in teaching German; and gladly accepted the offer to move out to Kilgowrie, where he was established in a cottage close to the house, where his wife aided in the housework. He became a companion of Fergus in his walks and rambles and, being an honest and pleasant fellow, the lad took to him; and after a few months their conversation, at first somewhat disjointed, became easy and animated. He learned, too, much from him as to the use of his sword. The Scotch clansmen used their claymores chiefly for striking; but under Rudolph's tuition the lad came to be as apt with the point as he had before been with the edge, and fully recognized the great advantages of the former. By the time he reached the age of sixteen, his skill with the weapon was fully recognized by the young clansmen who, on occasions of festive gatherings, sometimes came up to try their skill with the young laird.

From Rudolph, too, he came to know a great deal of the affairs of Europe, as to which he had hitherto been profoundly ignorant. He learned how, by the capture of the province of Silesia from the Empress of Austria, the King of Prussia had, from a minor principality, raised his country to a considerable power, and was regarded with hostility and jealousy by all his neighbours.

"But it is only a small territory now, Rudolph," Fergus said.

"'Tis small, Master Fergus, but the position is a very strong one. Silesia cannot well be invaded, save by an army forcing its way through very formidable defiles; while on the other hand, the Prussian forces can suddenly pour out into Saxony or Hanover. Prussia has perhaps the best-drilled army in Europe, and though its numbers are small in proportion to those which Austria can put in the field, they are a compact force; while the Austrian army is made up of many peoples, and could not be gathered with the speed with which Frederick could place his force in the field.

"The king, too, is himself, above all things, a soldier. He has good generals, and his troops are devoted to him, though the discipline is terribly strict. It is a pity that he and the King of England are not good friends. They are natural allies, both countries being Protestant; and to say the truth, we in Hanover should be well pleased to see them make common cause together, and should feel much more comfortable with Prussia as our friend than as a possible enemy.

"However, 'tis not likely that, at present, Prussia will turn her hand against us. I hear, by letters from home, that it is said that the Empress of Russia, as well as the Empress of Austria, both hate Frederick; the latter because he has stolen Silesia from her; the former because he has openly said things about her such as a woman never forgives. Saxony and Poland are jealous of him, and France none too well disposed. So at present the King of Prussia is like to leave his neighbours alone; for he may need to draw his sword, at any time, in self defence."

It was but a few days after this that Maggie Drummond received this short letter from her cousin, Marshal James Keith:

"My dear Cousin,

"By your letter, received a few days since, I learned that Fergus is now nearly sixteen years old; and is, you say, as well grown and strong as many lads two or three years older. Therefore it is as well that you should send him off to me, at once. There are signs in the air that we shall shortly have stirring times, and the sooner he is here the better. I would send money for his outfit; but as your letter tells me that you have, by your economies, saved a sum ample for this purpose, I abstain from doing so. Let him come straight to Berlin, and inquire for me at the palace. I have a suite of apartments there; and he could not have a better time for entering upon military service; nor a better master than the king, who loves his Scotchmen, and under whom he is like to find opportunity to distinguish himself."

A week later, Fergus started. It needed an heroic effort, on the part of his mother, to let him go from her; but she had, all along, recognized that it was for the best that he should leave her. That he should grow up as a petty laird, where his ancestors had been the owners of wide estates, and were powerful chiefs with a large following of clansmen and retainers, was not to be thought of. Scotland offered few openings, especially to those belonging to Jacobite families; and it was therefore deemed the natural course, for a young man of spirit, to seek his fortune abroad and, from the days of the Union, there was scarcely a foreign army that did not contain a considerable contingent of Scottish soldiers and officers. They formed nearly a third of the army of Gustavus Adolphus, and the service of the Protestant princes of Germany had always been popular among them.

Then, her own cousin being a marshal in the Prussian army, it seemed to Mrs. Drummond almost a matter of course, when the time came, that Fergus should go to him; and she had, for many years, devoted herself to preparing the lad for that service. Nevertheless, now that the time had come, she felt the parting no less sorely; but she bore up well, and the sudden notice kept her fully occupied with preparations, till the hour came for his departure.

Two of the men rode with him as far as Leith, and saw him on board ship. Rudolph had volunteered to accompany him as servant, but his mother had said to the lad:

"It would be better not, Fergus. Of course you will have a soldier servant, there, and there might be difficulties in having a civilian with you."

It was, however, arranged that Rudolph should become a member of the household. Being a handy fellow, a fair carpenter, and ready to turn his hand to anything, there would be no difficulty in making him useful about the farm.

Fergus had learnt, from him, the price at which he ought to be able to buy a useful horse; and his first step, after landing at Stettin and taking up his quarters at an inn, was to inquire the address of a horse dealer. The latter found, somewhat to his surprise, that the young Scot was a fair judge of a horse, and a close hand at driving a bargain; and when he left, the lad had the satisfaction of knowing that he was the possessor of a serviceable animal, and one which, by its looks, would do him no discredit.

Three days later he rode into Berlin. He dismounted at a quiet inn, changed his travelling dress for the new one that he carried in his valise, and then, after inquiring for the palace, made his way there.

He was struck by the number of soldiers in the streets, and with the neatness, and indeed almost stiffness, of their uniform and bearing. Each man walked as if on parade, and the eye of the strictest martinet could not have detected a speck of dust on their equipment, or an ill-adjusted strap or buckle.

"I hope they do not brace and tie up their officers in that style," Fergus said to himself.

He himself had always been accustomed to a loose and easy attire, suitable for mountain work; and the high cravats and stiff collars, powdered heads and pigtails, and tight-fitting garments, seemed to him the acme of discomfort. It was not long, however, before he came upon a group of officers, and saw that the military etiquette was no less strict, in their case, than in that of the soldiers, save that their collars were less high, and their stocks more easy. Their walk, too, was somewhat less automatic and machine-like, but they were certainly in strong contrast to the British officers he had seen, on the occasions of his one or two visits to Perth.

On reaching the palace, and saying that he wished to see Marshal Keith, he was conducted by a soldier to his apartment; and on the former taking in the youth's name, he was at once admitted. The marshal rose from his chair, came forward, and shook him heartily by the hand.

"So you are Fergus Drummond," he said, "the son of my cousin Maggie! Truly she lost no time in sending you off, after she got my letter. I was afraid she might be long before she could bring herself to part from you."

"She had made up her mind to it so long, sir, that she was prepared for it; and indeed, I think that she did her best to hurry me off as soon as possible, not only because your letter was somewhat urgent, but because it gave her less time to think."

"That was right and sensible, lad, as indeed Maggie always was, from a child.

"She did not speak too strongly about you, for indeed I should have taken you for fully two years older than you are. You have lost no time in growing, lad, and if you lose no more in climbing, you will not be long before you are well up the tree.

"Now, sit you down, and let me first hear all about your mother, and how she fares."

"In the first place, sir, she charged me to give you her love and affection, and to thank you for your good remembrance of her, and for writing to her so often, when you must have had so many other matters on your mind."

"I was right glad when I heard that they had given her back Kilgowrie. It is but a corner of your father's lands; but I remember the old house well, going over there once, when I was staying with your grandfather, to see his mother, who was then living there. How much land goes with it?"

"About a thousand acres, but the greater part is moor and mountain. Still, the land suffices for her to live on, seeing that she keeps up no show, and lives as quietly as if she had never known anything better."

"Aye, she was ever of a contented spirit. I mind her, when she was a tiny child; if no one would play with her, she would sit by the hour talking with her dolls, till someone could spare time to perch her on his shoulder, and take her out."

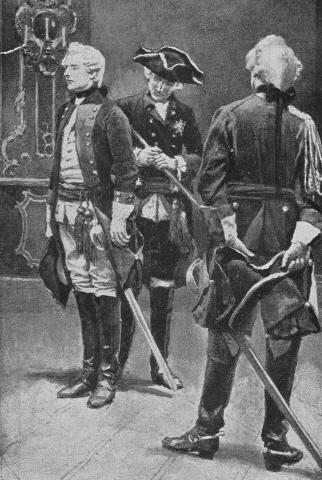

Marshal Keith was a tall man, with a face thoughtful in repose, but having a pleasant smile, and an eye that lit up with quiet humour when he spoke. He enjoyed the king's confidence to the fullest extent, and was regarded by him not only as a general in whose sagacity and skill he could entirely rely, but as one on whose opinion he could trust upon all political questions. He was his favourite companion when, as happened not unfrequently, he donned a disguise and went about the town, listening to the talk of the citizens and learning their opinions upon public affairs.

"I have spoken to the king about your coming, lad, and told him that you were a kinsman of mine.

"'Indeed, marshal,' the king said, 'from what I can see, it appears to me that all Scotchmen are more or less kin to each other.'

"'It is so to some extent, your majesty. We Scotchmen pride ourselves on genealogy, and know every marriage that has taken place, for ages past, between the members of our family and those of others; and claim as kin, even though very distant, all those who have any of our blood running in their veins. But in this case the kinship is close, the lad's mother being a first cousin of mine. His father was killed at Culloden, and I promised her, as soon as the news came to me, that when he had grown up strong and hearty he should join me, wherever I might be, and should have a chance of making his fortune by his sword.'

"'You say that he speaks both French and German well? It is more than I can do,' the king said with a laugh. 'German born and German king as I am, I get on but badly when I try my native tongue, for from a child I have spoken nothing but French. Still, it is well that he should know the language. In my case it matters but little, seeing that all my court and all my generals speak French. But one who has to give orders to soldiers should be understood by them.

"'Well, what do you want me to do for the lad?'

"'I propose to make him one of my own aides-de-camp,' I replied, 'and therefore I care not so much to what regiment he is appointed; though I own that I would far rather see him in the uniform of the guards, than any other.'

"'You are modest, marshal; but I observe that it is a common fault among your countrymen. Well, which shall it be--infantry or cavalry?'

"'Cavalry, since you are good enough to give me the choice, sire. The uniform looks better, for an aide-de-camp, than that of the infantry.'

"'Very well, then, you may consider him gazetted as a cornet, in my third regiment of Guards. You have no more kinsmen coming at present, Keith?'

"'No, sire; not at present.'

"'If many more come, I shall form them into a separate regiment.'

"'Your majesty might do worse,' I said.

"The king nodded. 'I wish I had half a dozen Scotch regiments; aye, a score or two. They were the cream of the army of Gustavus Adolphus, and if matters turn out as I fear they will, it would be a welcome reinforcement.'

"I will give you a note presently," continued the marshal, "to a man who makes my uniforms, so that I may present you to the king, as soon as you are enrolled. You must remember that your favour, or otherwise, with him will depend very largely upon the fit of your uniform, and the manner in which you carry yourself. There is nothing so unpardonable, in his eyes, as a slovenly and ill-fitting dress. Everything must be correct, to a nicety, under all circumstances. Even during hot campaigns, you must turn out in the morning as if you came from a band box.

"I will get Colonel Grunow, who commands your regiment, to tell off an old trooper, one who is thoroughly up to his work, as your servant. I doubt not that he may be even able to find you a Scotchman, for there are many in the ranks--gentlemen who came over after Culloden, and hundreds of brave fellows who escaped Cumberland's harryings by taking ship and coming over here, where, as they supposed, they would fight under a Protestant king."

"But the king is a Protestant, is he not, sir?"

"He is nominally a Protestant, Fergus. Absolutely, his majesty has so many things to see about that he does not trouble himself greatly about religion. I should say that he was a disciple of Voltaire, until Voltaire came here; when, upon acquaintance, he saw through the vanity of the little Frenchman, and has been much less enthusiastic about him since.

"By the way, how did you come here?"

"We heard of a ship sailing for Stettin, and that hurried my departure by some days. I made a good voyage there, and on landing bought a horse and rode here."

"Well, I am afraid your horse won't do to carry one of my aides-de-camp, so you had best dispose of it, for what it will fetch. I will mount you myself. His majesty was pleased to give me two horses, the other day, and my stable is therefore over full.

"Now, Fergus, we will drink a goblet of wine to your new appointment, and success to your career."

"From what you said in your letter to my mother, sir, you think it likely that we shall see service, before long?"

"Aye, lad, and desperate service, too. We have--but mind, this must go no further--sure news that Russia, Austria, France, and Saxony have formed a secret league against Prussia, and that they intend to crush us first, and then partition the kingdom among themselves. The Empress of Austria has shamelessly denied that any such treaty exists, but tomorrow morning a messenger will start, with a demand from the king that the treaty shall be publicly acknowledged and then broken off, or that he will at once proclaim war. If we say nine days for the journey there, nine days to return, and three days waiting for the answer, you see that in three weeks from the present we may be on the move, for our only chance depends upon striking a heavy blow before they are ready. We have not wasted our time. The king has already made an alliance with England."

"But England has no troops, or scarcely any," Fergus said.

"No, lad, but she has what is of quite as much importance in war--namely, money, and she can grant us a large subsidy. The king's interest in the matter is almost as great as ours. He is a Hanoverian more than an Englishman, and you may be sure that, if Prussia were to be crushed, the allies would make but a single bite of Hanover. You see, this will be a war of life and death to us, and the fighting will be hard and long."

"But what grievance has France against the king?"

"His majesty is open spoken, and no respecter of persons; and a woman may forgive an injury, but never a scornful gibe. It is this that has brought both France and Russia on him. Madame Pompadour, who is all powerful, hates Frederick for having made disrespectful remarks concerning her. The Empress of Russia detests him, for the same reason. She of Austria has a better cause, for she has never forgiven the loss of Silesia; and it is the enmity of these women, as much as the desire to partition Prussia, that is about to plunge Europe into a war to the full as terrible as that of the thirty years."

Keith now rung a bell, and a soldier entered.

"Tell Lieutenant Lindsay that I wish to speak to him."

A minute later an officer entered the room, and saluted stiffly.

"Lindsay, this is a young cousin of mine, Fergus Drummond. The king has appointed him to a cornetcy in the 3rd Royal Dragoon Guards, but he is going to be one of my aides-de-camp. Now that things are beginning to move, you and Gordon will need help.

"Take him first to Tautz. I have written a note to the man, telling him that he must hurry everything on. There is still a spare room on your corridor, is there not? Get your man to see his things bestowed there. I shall get his appointment this evening, I expect, but it will be a day or two before he will be able to get a soldier from his regiment. He has a horse to sell, and various other matters to see to. At any rate, look after him, till tomorrow. 'Tis my hour to go to the king."

Lindsay was a young man of two or three and twenty. He had a merry, joyous face, a fine figure, and a good carriage; but until he and Fergus were beyond the limits of the palace, he walked by the lad's side with scarce a word. When once past the entrance, however, he gave a sigh of relief.

"Now, Drummond," he said, "we will shake hands, and begin to make each other's acquaintance. First, I am Nigel Lindsay, very much at your service. On duty I am another person altogether, scarcely recognizable even by myself--a sort of wooden machine, ready, when a button is touched, to bring my heels smartly together, and my hand to the salute. There is something in the air that stiffens one's backbone, and freezes one from the tip of one's toes to the end of one's pigtail. When one is with the marshal alone, one thaws; for there is no better fellow living, and he chats to us as if we were on a mountain side in Scotland, instead of in Frederick's palace. But one is always being interrupted; either a general, or a colonel, or possibly the king himself, comes in.

"For the time, one becomes a military statue; and even when they go, it is difficult to take up the talk as it was left. Oh, it is wearisome work, and heartily glad I shall be, when the trumpets blow and we march out of Berlin. However, we are beginning to be pretty busy. I have been on horseback, twelve hours a day on an average, for the past week. Gordon started yesterday for Magdeburg, and Macgregor has been two days absent, but I don't know where. Everyone is busy, from the king himself--who is always busy about something--to the youngest drummer. Nobody outside a small circle knows what it is all about. Apparently we are in a state of profound peace, without a cloud in the sky, and yet the military preparations are going on actively, everywhere.

"Convoys of provisions are being sent to the frontier fortresses. Troops are in movement from the Northern Provinces. Drilling is going on--I was going to say night and day, for it is pretty nearly that--and no one can make out what it is all about.

"There is one thing--no one asks questions. His majesty thinks for his subjects, and as he certainly is the cleverest man in his dominions, everyone is well content that it should be so.

"And now, about yourself. I am running on and talking nonsense, when I have all sorts of questions to ask you. But that is always the way with me. I am like a bottle of champagne, corked down while I am in the palace, and directly I get away the cork flies out by itself, and for a minute or two it is all froth and emptiness.

"Now, when did you arrive, how did you arrive, what is the last news from Scotland, which of the branches of the Drummonds do you belong to, and how near of kin are you to the marshal? Oh, by the way, I ought to know the last without asking; as you are a Drummond, and a relation of Keith, you can be no other than the son of the Drummond of Tarbet, who married Margaret Ogilvie, who was a first cousin of Keith's."

"That is right," Fergus said. "My father fell at Culloden, you know. As to all your other questions, they are answered easily enough. I know very little of the news in Scotland, for my mother lived a very secluded life at Kilgowrie, and little news came to us from without. I came from Leith to Stettin, and there I bought a horse and rode on here."

His companion laughed.

"And how about yourself? I suppose you know nothing of this beastly language?"

"Yes; I can speak it pretty fluently, and of course know French."

"I congratulate you, though how you learnt it, up in the hills, I know not. I did not know a word of it, when I came out two years ago; and it is always on my mind, for of course I have a master who, when I am not otherwise engaged, comes to me for an hour a day, and well nigh maddens me with his crack-jaw words; but I don't seem to make much progress. If I am sent with an order, and the officer to whom I take it does not understand French, I am floored. Of course I hand the order, if it is a written one, to him. If it is not, but just some verbal message, asking him to call on the marshal at such and such a time, I generally make a horrible mess of it. He gets in a rage with me, because he cannot understand me. I get in a rage with him, for his dulness; and were it not that he generally manages to find some other officer, who does understand French, the chances are very strongly against Keith's message being attended to.

"First of all, I will take you to our quarters. That is the house."

"Why, I thought you lodged in the palace?"

"Heaven forbid! Macgregor has a room in the chief's suite of apartments. He is senior aide-de-camp, and if there is any message to be sent late, he takes it; but that is not often the case. Gordon lodges here with me. The house is a sort of branch establishment to the palace. Malcolm Menzies and Horace Farquhar, two junior aides of the king, are in the same corridor with us. Of course we make up a party by ourselves. Then there are ten or twelve German officers--some of them aides-de-camp of the Princes Maurice and Henry, the Prince of Bevern and General Schwerin--besides a score or so of palace officials.

"Fortunately the Scotch corridor, as we call it, has a separate entrance, so we can go in or out without disturbing anyone. It is a good thing, for in fact we and the Prussians do not get on very well together. They have a sort of jealousy of us; which is, I suppose, natural enough. Foreigners are never favourites, and George's Hanoverian officers are not greatly loved in London. I expect a campaign will do good, that way. They will see, at any rate, that we don't take our pay for nothing, and are ready to do a full share and more of fighting; while we shall find that these stiff pipe-clayed figures are brave fellows, and good comrades, when they get a little of the starch washed out of them.

"Now, this is my room, and I see my man has got dinner ready."

Chapter 2: Joining.

In answer to the shout of "Donald," a tall man in the pantaloons of a Prussian regiment, but with his tunic laid aside, came out from a small room that served as a kitchen, and dormitory, for himself.

"I am just ready, sir," he said. "Hearing you talking as you came along, and not knowing who you might have with you, I just ran in to put on my coat; but as you passed, and I heard it was Scottish you were speaking, I knew that it didna matter."

"Put another plate and goblet on the table, Donald. I hope that you have meat enough for two of us."

"Plenty for four," the soldier said. "The market was full this morning, and the folk so ta'en up wi' this talk of war, and so puzzled because no one could mak' out what it was about, that they did more gossiping than marketing. So when the time came for the market to close, I got half a young pig at less than I should hae paid for a joint, as the woman did not want to carry it home again."

"That is lucky. As you are from Perth, Donald, it is possible you may know this gentleman. He is Mr. Fergus Drummond, of Tarbet."

"I kenned his father weel; aye, and was close beside him at Culloden, for when our company was broken I joined one that was making a stand, close by, and it was Drummond who was leading it. Stoutly did we fight, and to the end stood back to back, hewing with our claymores at their muskets.

"At last I fell, wounded, I couldna say where at the time. When I came to myself and, finding that all was quiet, sat up and felt myself over, I found that it was a musket bullet that had ploughed along the top of my head, and would ha' killed me had it not been that my skull was, as my father had often said when I was a boy, thicker than ordinary. There were dead men lying all about me; but it was a dark night, and as there was no time to be lost if I was to save my skin, I crawled away to some distance from the field; and then took to my heels, and did not stop till next morning, when I was far away among the hills."

While he was talking, Donald had been occupied in adding a second plate and knife and fork and glass, and the two officers sat down to their meal. Fergus asked the soldier other questions as to the fight in which his father had lost his life; for beyond that he had fought to the last with his face to the foe, the lad had never learnt any particulars, for of the clansmen who had accompanied his father not one had ever returned.

"Mr. Drummond will take the empty room next to mine, Donald. I am going down now with him, to the inn where he has left his horse. As he has a few things there, you had best come with us and bring them here."

The landlord of the inn, on hearing that Fergus wished to sell his horse, said that there were two travellers in the house who had asked him about horses; as both had sold, to officers, fine animals they had brought in from the country, there being at present a great demand for horses of that class. One of these persons came in as they were speaking, and after a little bargaining Fergus sold the horse to him, at a small advance on the price he had given for it at Stettin. The landlord himself bought the saddle and bridle, for a few marks; saying that he could, at any time, find a customer for such matters. Donald took the valises and cloak, and carried them back to the palace.

"That matter is all comfortably settled," Lindsay said. "Now we are free men, but my liberty won't last long. I shall have to go on duty again, in half an hour. But at any rate, there is time to go first with you to the tailor's, and put your uniform in hand."

"I wish to be measured for the uniform of the 3rd Royal Dragoon Guards," Fergus said, as he entered the shop and the proprietor came up to him.

"Yes, Herr Tautz; and his excellency, Marshal Keith," Lindsay put in, "wishes you to know that the dress suit must be made instantly, or quicker if possible; for his majesty may, at any moment, order Mr. Drummond to attend upon him. Mr. Drummond is appointed one of the marshal's aides-de-camp; and as, therefore, he will often come under the king's eye, you may well believe that the fit must be of the best, or you are likely to hear of it, as well as Mr. Drummond."

"I will put it in hand at once, lieutenant. It shall be cut out without delay; and in three hours, if Mr. Drummond will call here, it shall be tacked together in readiness for the first trying on. By eight o'clock tomorrow morning it shall be ready to be properly fitted, and unless my men have bungled, which they very seldom do, it shall be delivered by midday."

"Mr. Drummond lodges in the next room to myself," the lieutenant said; "and my servant is looking after him, till he gets one of his own, so you can leave it with him."

While the conversation was going on, two of the assistants were measuring Fergus.

"Will you have the uniform complete, with belts, helmet, and all equipments?"

"Everything except the sword," Fergus said.

"At least I suppose, Lindsay, we can carry our own swords."

"Yes, the king has made that concession, which is a wonderful one, for him, that Scottish officers in his service may carry their own swords. You see, ours are longer and straighter than the German ones, and most of us have learnt our exercises with them, and certainly we would not fight so well with others; besides, the iron basket protects one's hand and wrist vastly better than the foreign guard. The concession was first made only to generals, field officers and aides-de-camp; but Keith persuaded the king, at last, to grant it to all Scottish officers, pointing out that they were able to do much better service with their own claymores, than with weapons to which they were altogether unaccustomed; and that Scottish men were accustomed to fight with the edge, and to strike downright sweeping blows, whereas the swords here are fitted only for the point, which, although doubtless superior in a duel, is far less effective in a general melee."

"I should certainly be sorry to give up my own sword," Fergus said. "It was one of my father's, and since the days when I was big enough to begin to use it, I have always exercised myself with it; though I, too, have learned to use the point a great deal, as I had a German instructor, as well as several Scottish ones."

"Except in a duel," Lindsay said, "I should doubt if skill goes for very much. I have never tried it myself, for I have never had the luck to be in battle; but I fancy that in a cavalry charge strength goes for more than skill, and the man who can strike quickly and heavily will do more execution than one trained to all sorts of nice points and feints. I grant that these are useful, when two men are watching each other; but in the heat of a battle, when every one is cutting and thrusting for his life, I cannot think that there is any time for fooling about with your weapon."

They had by this time left the shop, and were strolling down the streets.

"Is there much duelling here?"

"It is strictly forbidden," Lindsay said, with a laugh; "but I need hardly say that there is a good deal of it. Of course, pains are taken that these affairs do not come to his majesty's ears. Fever, or a fall from a horse, account satisfactorily enough for the absence of an officer from parade, and even his total disappearance from the scene can be similarly explained. Should the affair come to the king's ears, 'tis best to keep out of his way until it has blown over.

"Of course, with us it does not matter quite so much as with Prussian officers. Frederick's is not the only service open to us. Good swords are welcome either at the Russian or Austrian courts, to say nothing of those of half a dozen minor principalities. At all of these we are sure to find countrymen and friends, and if England really enters upon the struggle--and it seems to me that if there is a general row she can scarcely stand aloof--men who have learned their drill and seen some service might be welcomed, even if their fathers wielded their arms on the losing side, ten years ago.

"Of course, to a Prussian officer it would be practical ruin to be dismissed from the army. This is so thoroughly well understood that, in cases of duels, there is a sort of general conspiracy on the part of all the officers and surgeons of a regiment to hush the matter up. Still, if an officer is insulted--or thinks that he is insulted, which is about the same thing--he fights, and takes the consequences.

"I am not altogether sorry that I am an aide-de-camp, and I think that you can congratulate yourself on the same fact; for we are not thrown, as is a regimental officer, into the company of Prussians, and there is therefore far less risk of getting into a quarrel.

"I have no doubt the marshal, himself, will give you a few lessons shortly. He is considered to be one of the finest swordsmen in Europe, and in many respects he is as young as I am, and as fond of adventure. He gave me a few when I first came to him, but he said that it was time thrown away, for that I must put myself in the hands of some good maitre d'armes before he could teach me anything that would be useful. I have been working hard with one since, and know a good deal more about it than I did; but my teacher says that I am too hot and impetuous to make a good swordsman, and that though I should do well enough in a melee, I shall never be able to stand up against a cool man, in a duel. Of course the marshal had no idea of teaching me arms, but merely, as he said, of showing me a few passes that might be useful to me, on occasion. In reality he loves to keep up his sword play, and once or twice a week Van Bruff, who is the best master in Berlin, comes in for half an hour's practice with him, before breakfast."

After Lindsay had left him at the entrance to the palace, Fergus wandered about the town for some hours, and then went to the tailor's and had his uniform tried on. Merely run together though it was, the coat fitted admirably.

"You are an easy figure to fit, Herr Drummond," the tailor said. "There is no credit in putting together a coat for you. Your breeches are a little too tight--you have a much more powerful leg than is common--but that, however, is easily altered.

"Here are a dozen pairs of high boots. I noticed the size of your foot, and have no doubt that you will find some of these to fit you."

This was indeed the case, and among a similar collection of helmets, Fergus also had no difficulty in suiting himself.

"I think that you will find everything ready for you by half-past eight," the tailor said, "and I trust that no further alteration will be required. Six of my best journeymen will work all night at the clothes; and even should his majesty send for you by ten, I trust that you will be able to make a proper appearance before him, though at present I cannot guarantee that some trifling alteration will not be found necessary, when you try the uniforms on."

Fergus supped with the marshal, who had now time to ask him many more questions about his home life, and the state of things in Scotland.

"'Tis a sore pity," he said, "that we Scotchmen and Irishmen, who are to be found in such numbers in every European army, are not all arrayed under the flag of our country. Methinks that the time is not far distant when it will be so. I am, as you know, a Jacobite; but there is no shutting one's eyes to the fact that the cause is a lost one. The expedition of James the Third, and still more that of Charles Edward, have caused such widespread misery among the Stuarts' friends that I cannot conceive that any further attempt of the same kind will be made.

"In fact, there is no one to make it. The prince has lost almost all his friends, by his drunken habits and his quarrelsome and overbearing disposition. He has gone from court to court as a suppliant, but has everywhere alienated the sympathies of those most willing to befriend him. I may say that as a King of England and Scotland he is now impossible, and his own habits have done more to ruin his cause than even the defeat of Culloden. There are doubtless many, in both countries, who consider themselves Jacobites, but it is a matter of sentiment and not of passion.

"At any rate, there is no head to the cause now, and cannot possibly be unless the prince had a son; therefore, for at least five-and-twenty years, the cause is dead. Even if the prince leaves an heir, it would be absurd to entertain the idea that, after the Stuarts have been expelled from England a hundred years, any Scotchman or Englishman would be mad enough to risk life and property to restore them to the throne.

"Another generation and the Hanoverians will have become Englishmen, and the sentiment against them as foreigners will have died out. Then there will be no reason why Scotchmen and Irishmen should any longer go abroad, and all who wish it will be able to find employment in the army of their own country.

"This, indeed, might have happened long before this, had the Georges forgotten that they were Electors of Hanover as well as Kings of Great Britain; and had surrounded themselves with Englishmen instead of filling their courts with Germans, whose arrogance and greed made them hateful to Englishmen, and kept before their eyes the fact that their kings were foreigners. Hanover is a source of weakness instead of strength to Great Britain, and its loss would be an unmixed benefit to her; for as long as it remains under the British crown, so long must Britain play a part in European politics--a part, too, sometimes absolutely opposed to the interests of the country at large."

After supper was over, two general officers dropped in for a chat with the marshal. He introduced Fergus to them, and the latter then retired and joined the little party of Scottish officers at Lindsay's quarters. Lindsay introduced him to them, and he was very heartily received, and it was not until very late that they turned into bed.

At half-past eight next morning Fergus went to the tailor's, and found that he had kept his promise, to the letter. The uniforms fitted admirably, and were complete in every particular. As Marshal Keith had, the evening before, informed him that he had received his appointment to the 3rd Royal Dragoon Guards, he had no hesitation in putting on a uniform when, a quarter of an hour later, it arrived at his quarters. Donald went out and fetched a hairdresser, who combed, powdered, and tied up his hair in proper military fashion. When he left, Donald took him in hand, attired him in his uniform, showed him the exact angle at which his belt should be worn, and the military salute that should be given.

It was fortunate that he was in readiness, for at half-past ten Lindsay came in with a message from the marshal that he was, at once, to repair to the palace, with or without a uniform; as the king had sent to say that he should visit Keith at eleven, and that he could then present his cousin to him.

It could not be said that Fergus felt comfortable, as he started from his quarters. Accustomed to a loose dress and light shoes, he felt stiff and awkward in his tight garments, closely buttoned up, and his heavy jack boots; and he found himself constrained to walk with the same stiffness and precision that had amused him in the Prussian officers, on the previous day.

"So you have got your uniform," the marshal said, as Fergus entered and saluted, as Donald had instructed him. "It becomes you well, lad, and the king will be pleased at seeing you in it. He could not have blamed you had it not been ready, for the time has been short, indeed; but he will like to see you in it, and will consider that it shows alacrity and zeal."

Presently the door opened and, as the marshal rose and saluted, Fergus knew that it was the king. He had never had the king described to him, and had depicted to himself a stiff and somewhat austere figure; but the newcomer was somewhat below middle height, with a kindly face, and the air rather of a sober citizen than of a military martinet. The remarkable feature of his face were his eyes, which were very large and blue, with a quick piercing glance that seemed to read the mind of anyone to whom he addressed himself. So striking were they that the king, when he went about the town in disguise, was always obliged to keep his eyes somewhat downcast; as, however well made up, they would have betrayed him at once, had he looked fixedly at anyone who had once caught sight of his face.

"Good morning, marshal!" he said, in a friendly tone. "So this is my last recruit--a goodly young fellow, truly."

He walked round Fergus as if he were examining a lay figure, closely scrutinizing every article of his appointment, and then gave a nod of approbation.

"Always keep yourself like that, young sir. An officer is unfit to take charge of men, unless he can set an example of exactness in dress. If a man is precise in little things, he will be careful in other matters.

"Although he is going to be your aide-de-camp, Keith, he had better go to his regimental barracks, and drill for a few hours a day, if you can spare him."

"He shall certainly do so, sire. I spoke to his colonel yesterday evening, and told him that I would myself take the lad down to him, this morning, and present him to his comrades of the regiment. It would be well if he could have six months' drilling, for an aide-de-camp should be well acquainted with the meaning of the orders he carries; as he is, in that case, far less likely to make mistakes than he would otherwise be. Your majesty has nothing more to say to him?"

"Nothing. I hope he is not quarrelsome. But there, it is of no use my hoping that, Keith; for your Scotchman is a quarrelsome creature by nature, at least so it seems to me. Of the duels that, in spite of my orders, take place--I know you all try to hide them from me, Keith--I hear of a good many between these hot-headed countrymen of yours and my Prussian officers."

"With deference to your majesty, I don't think that that proves much. It would be as fair to say that these duels show how aggressive are your Prussian officers towards my quiet and patient countrymen.

"Now you can retire, cornet."

Fergus gave the military salute, and retired to the anteroom.

"Have you passed muster?" Lindsay asked with a laugh.

"Yes; at least the king found nothing wrong. He was not at all what I thought he would be."

"No; I was astonished myself, the first time I saw him. He is a capital fellow, in spite of his severity in matters of military etiquette and discipline. He is very kind hearted, does not stand at all upon his dignity, bears no malice, and very soon remits punishment he has given in the heat of the moment. I think that he regards us Scots as being a people for whom allowances must be made, on the ground of our inborn savagery and ignorance of civilized customs. He does not mind plain speaking on our part and, if in the humour, will talk with us much more familiarly than he would do to a Prussian officer."

In a few minutes the bell in the next room sounded. Lindsay went in.

"Are the horses at the door?"

"Yes, marshal."

"Then we will mount at once. I told the colonel of the 3rd that I should be at the barracks by twelve o'clock, unless the king wanted me on his business."

Fergus had already put on his helmet, and he and Lindsay followed Keith downstairs. In the courtyard were the horses, which were held by orderlies.

"That is yours, Fergus," Keith said. "It has plenty of bone and blood, and should carry you well for any distance."

Fergus warmly thanked the marshal for the gift. It was a very fine horse, and capable of carrying double his weight. It was fully caparisoned with military bridle and saddle and horse cloth.

They mounted at once. The orderlies ran to their horses, which were held by a mounted trooper, and the four fell in behind the officers. Lindsay and Fergus rode half a length behind the marshal, but the latter had some difficulty in keeping his horse in that position.

The marshal smiled.

"It does not understand playing second fiddle, Fergus. You see, it has been accustomed to head the procession."

As they rode along through the street, all officers and soldiers stood as stiff as statues at the salute, the marshal returning it as punctiliously, though not as stiffly. In a quarter of an hour they arrived at the gate of a large barracks. The guard turned out as soon as the marshal was seen approaching, and a trumpet call was heard in the courtyard as they entered the gate.

Fergus was struck with the spectacle, the like of which he had never seen before. The whole regiment was drawn up in parade order. The colonel was some distance in the front, the officers ranged at intervals behind him. Suddenly the colonel raised his sword above his head, a flash of steel ran along the line, eight trumpeters sounded the first note of a military air, and the regiment stood at the salute, men and horses immovable, as if carved in stone. A minute later the music stopped, the colonel raised his sword again, there was another flash of steel, and the salute was over. Then the colonel rode forward to meet the marshal.

"Nothing could have been better, my dear colonel," the latter said. "As I told you yesterday, my inspection of your regiment is but a mere form, for I know well that nothing could be more perfect than its order; but I must report to the king that I have inspected all the regiments now in Berlin and Potsdam, and others that will form my command, should any untoward event disturb the peace of the country.

"But before I begin, permit me to present to you this young officer, who was yesterday appointed to your regiment. I have already spoken to you of him. This is Cornet Fergus Drummond, a cousin of my own, and whom I recommend strongly to you. As I informed you, he will for the present act as one of my aides-de-camp."

"You have lost no time in getting your uniform, Mr. Drummond," the colonel said. "I am sure that you will be most cordially received, by all my officers as by myself, as a relation of the marshal, whom we all respect and love."

"I will now proceed to the inspection," the marshal said, and he proceeded towards the end of the line.

The colonel rode beside him, but a little behind. The two aides-de-camp followed, and the four troopers brought up the rear. They proceeded along the front rank, the officers having before this taken up their position in the line. The marshal looked closely at each man as he passed, horse as well as man being inspected.

"I do not think, colonel, that the king himself could have discovered the slightest fault or blemish. The regiment is simply perfect. I hope that during the next few days you will have every shoe inspected by the farrier, and every one showing the least signs of wear taken off and replaced; and that you will also direct the captains of troops to see that the men's kits are in perfect order."

"That shall be done, sir, though I own that I cannot see against whom we are likely to march; for though the air is full of rumours, all our neighbours seem to think of nothing so little as war."

"It may be," Keith said with a smile, "that it is merely his majesty's intention to see in how short a time we can place an army, complete in every particular and ready for a campaign, in the field. His majesty is fond of trying military experiments."

"I hope, marshal, that you will do us the honour of drinking a goblet of champagne with us. Some of my officers have not yet been presented to you, and I shall be glad to take the opportunity of doing so."

"With pleasure, colonel. A good offer should never be refused."

By this time they had moved to the front of the regiment.

"Officers and men of the 3rd Royal Dragoon Guards," Keith said in a loud voice, "I shall have great pleasure in reporting to the king the result of my inspection, that the regiment is in a state of perfect efficiency, and that I have been unable to detect the smallest irregularity or blemish. I am quite sure that, if you should at any time be called upon to fight the enemies of your country, you will show that your conduct and courage will be fully equal to the excellence of your appearance. I feel that whatever men can do you will do.

"God save the king!"

He lifted his plumed hat. The trumpet sounded, the men gave the royal salute, and then a loud cheer burst from the ranks; for the rumours current had raised a feeling of excitement throughout the regiment, and though no man could see from what point danger threatened, all felt that great events were at hand.

The regiment was then dismissed, hoarse words of command were shouted, and each troop moved off to its stable; while the colonel and Keith rode to the officers' anteroom, the trumpets at the same time sounding the officers' call. In a few minutes all were gathered there. The colonel first presented some of his young officers to the marshal, and then introduced Fergus to his new comrades, among whom were two Scotch officers.

"Mr. Drummond will, for the present, serve with the marshal as one of his aides-de-camp; but I hope that he will soon join the regiment where, at any rate, he will at all times find a warm welcome."

Keith had already told the colonel that, for the present, Fergus would be released from all duty as an aide-de-camp, and would spend his time in acquiring the rudiments of drill.

Champagne was now served round. The officers drank the health of the marshal, and he in return drank to the regiment; then all formality was laid aside for a time, and the marshal laughed and chatted with the officers, as if he had been one of themselves. Fergus was surrounded by a group, who were all pleased at finding that he could already talk the language fluently; and in spite of the jealousy of the Scottish officers, felt throughout the service, the impression that he made was a very favourable one; and the hostility of race was softened by the fact that he was a near relation of the marshal, who was universally popular. He won favour, too, by saying, when the colonel asked whether he would rather have a Scottish or a Prussian trooper assigned to him, as servant and orderly, that he would choose one of the latter.

After speaking to the adjutant the colonel gave an order and, two minutes later, a tall and powerful trooper entered the room and saluted. The adjutant went up to him.

"Karl Hoger," he said, "you are appointed orderly and servant to Mr. Fergus Drummond. He is quartered at the officers' house, facing the palace. You will take your horse round there, and await his arrival. He will show you where it is to be stabled. You are released from all regimental duty until further orders."

The man saluted and retired, without the slightest change of face to show whether the appointment was agreeable to him, or otherwise.

Half an hour later the marshal mounted and, with his party, rode back to the palace. After he had dismounted, Lindsay and Fergus rode across to their quarters. Karl Hoger was standing at the entrance, holding his horse. He saluted as the two officers came up.

"I will go in and see if dinner is ready," Lindsay said. "I told Donald that we should be back at half-past one, and it is nearly two now, and I am as hungry as a hunter."

Fergus led the way to the stable, and pointed out to the trooper the two stalls that the horses were to occupy; for each room in the officers' quarters had two stalls attached to it, the one for the occupant, the other for his orderly.

"I suppose you have not dined yet, Karl?"

"No, sir, but that does not matter."

"I don't want you to begin by fasting. Here are a couple of marks. When you have stabled the horses and finished here, you had better go out and get yourself dinner. I shall not be able to draw rations for you for today.

"After you have done, come to the main entrance where I met you and take the first corridor to the left. Mine is the fifth door on the right-hand side. If I am not in, knock at the next door to it on this side. You will see Lieutenant Lindsay's name on it.

"You need not be in any hurry over your meal, for I am just going to have dinner, and certainly shall not want you for an hour."

On reaching Lindsay's quarters Fergus found that dinner was waiting, and he and Lindsay lost no time in attacking a fine fish that Donald had bought in the market.

"That is a fine regiment of yours, Drummond," Lindsay said.

"Magnificent. Of course, I never saw anything like it before, but it was certainly splendid."

"Yes. They distinguished themselves in the campaigns of Silesia very much. Their colonel, Grim, is a capital officer--very strict, but a really good fellow, and very much liked by his officers. However, if I were you, I should be in no hurry to join. I had two years and a half in an infantry regiment, before Keith appointed me one of his aides-de-camp, and I can tell you it was hard work--drill from morning till night. We were stationed at a miserable country place, without any amusements or anything to do; and as at that time there did not seem the most remote chance of active service, it was a dog's life. Everyone was surly and ill tempered, and I had to fight two duels."

"What about?"

"About nothing, as far as I could see. A man said something about Scotch officers, in a tone I did not like. I was out of temper, and instead of turning it off with a laugh I took it up seriously, and threw a glass at his head. So of course we fought. We wounded each other twice, and then the others stopped it. The second affair was just as absurd, except that there I got the best of it, and sliced the man's sword arm so deeply that he was on the sick list for two months--the result of an accident, as the surgeon put it down. So although I don't say but that there is a much better class of men in the 3rd than there was in my regiment, I should not be in any hurry to join.

"If there is a row, you will see ten times as much as an aide-de-camp as you would in your regiment, while during peacetime there is no comparison at all between our lives as aides-de-camp and that of regimental officers.

"I fancy you have rather a treasure in the man they have told off to you. He was the colonel's servant at one time, but he got drunk one day, and of course the colonel had to send him back to the ranks. One of the officers told me about him when he came in, and said that he was one of the best riders and swordsmen in the regiment. The adjutant told me that he has specially chosen him for you, because he had a particularly good mount, and that as your orderly it would be of great importance that he should be able to keep up with you. Of course, he got the horse when he was the colonel's orderly; and though he was sent back to the ranks six months ago, the colonel, who was really fond of the man, allowed him to keep it."

"I thought it seemed an uncommonly good animal, when he led it into the stable," Fergus said. "Plenty of bone, and splendid quarters. I hope he was not unwilling to come to me. It is a great fall from being a colonel's servant to become a cornet's."

"I don't suppose he will mind that; and at any rate, while he is here the berth will be such an easy one that I have no doubt he will be well content with it, and I daresay that he and Donald will get on well together.

"Donald is a Cuirassier. After Keith appointed me as one of his aides, he got me transferred to the Cuirassiers, who are stationed at Potsdam. That was how I came to get hold of Donald as a servant."

A few minutes after they had done dinner, there was a knock at the door. The orderly entered and saluted.

"You will find my man in there," Lindsay said. "At present, Mr. Drummond and I are living together. I daresay you and he will get on very comfortably."

For the next fortnight, Fergus spent the whole day in barracks. He was not put through the usual preliminary work, but the colonel, understanding what would be most useful to him, had him instructed in the words of command necessary for carrying out simple movements, his place as cornet with a troop when in line or column; and being quick, intelligent, and anxious to learn, Fergus soon began to feel himself at home.

Chapter 3: The Outbreak Of War.

As Lindsay had predicted, the marshal had, on the evening of the day Fergus joined his regiment, said to him:

"I generally have half an hour's fencing the first thing of a morning, Fergus. It is good exercise, and keeps one's muscles lissome. Come round to my room at six. I should like to see what the instructors at home have done for you, and I may be able to put you up to a few tricks of the sword that may be of use to you, if you are ever called upon to break his majesty's edicts against duelling."

Fergus, of course, kept the appointment.

"Very good. Very good, indeed," the marshal said, after the first rally. "You have made the most of your opportunities. Your wrist is strong and supple, your eye quick. You are a match, now, for most men who have not worked hard in a school of arms. Like almost all our countrymen, you lack precision. Now, let us try again."

For a few minutes Fergus exerted himself to the utmost, but failed to get his point past the marshal's guard. He had never seen fencing like this. Keith's point seemed to be ever threatening him. The circles that were described were so small that the blade seemed scarcely to move; and yet every thrust was put aside by a slight movement of the wrist, and he felt that he was at his opponent's mercy the whole time. Presently there was a slight jerk and, on the instant, his weapon was twisted from his hand and sent flying across the room.

Keith smiled at his look of bewilderment.

"You see, you have much to learn, Fergus."

"I have indeed, sir. I thought that I knew something about fencing, but I see that I know nothing at all."

"That is going too far the other way, lad. You know, for example, a vast deal more than Lindsay did when he came to me, six months ago. I fancy you know more than he does now, or ever will know; for he still pins his faith on the utility of a slashing blow, as if the sabre had a chance against a rapier, in the hands of a skilful man. However, I will give you a lesson every morning, and I should advise you to go to Van Bruff every evening.

"I will give you a note to him. He is by far the best master we have. Indeed, he is the best in Europe. I will tell him that the time at your disposal is too short for you to attempt to become a thorough swordsman; but that you wish to devote yourself to learning a few thrusts and parries, such as will be useful in a duel, thoroughly and perfectly. I myself will teach you that trick I played on you just now, and two others like it; and I think it possible that in a short time you will be able to hold your own, even against men who may know a good deal more of the principles and general practice of the art than yourself."

Armed with a note from the marshal, Fergus went the next day to the famous professor. The latter read the letter through carefully, and then said:

"I should be very glad to oblige the marshal, for whom I have the highest respect, and whom I regard as the best swordsman in Europe. I often practise with him, and always come away having learned something. Moreover, the terms he offers, for me to give you an hour and a half's instruction every evening, are more than liberal. But every moment of my time in the evening is occupied, from five to ten. Could you come at that hour?"

"Certainly I could, professor."

"Then so be it. Come at ten, punctually. My school is closed at that hour, but you will find me ready for you."

Accordingly, during the next three weeks Fergus worked, from ten till half-past eleven, with Herr Van Bruff; and from six till half past with the marshal. His mountain training was useful indeed to him now; for the day's work in the barrack was in itself hard and fatiguing and, tough as his muscles were, his wrist at first ached so at nights that he had to hold it, for some time, under a tap of cold water to allay the pain. At the end of a week, however, it hardened again; and he was sustained by the commendations of his two teachers, and the satisfaction he felt in the skill he was acquiring.

"Where is your new aide-de-camp, marshal?" the king asked, one evening.

It was the close of one of his receptions.

"As a rule, these young fellows are fond of showing off in their uniforms, at first."

"He is better employed, sire. He has the makings of a very fine swordsman and, having some reputation myself that way, I should be glad that my young cousin should be able to hold his own well, when we get to blows with the enemy. So I and Van Bruff have taken him in hand, and for the last three weeks he has made such progress that this morning, when we had open play, it put me on my mettle to hold my own. So, what with that and his regimental work, his hands are more than full; and indeed, he could not get through it, had he to attend here in the evening; and I know that as soon as he has finished his supper he turns in for a sound sleep, till he is woke in time to dress and get to the fencing school, at ten. Had there been a longer time to spare, I would not have suffered him to work so hard; but seeing that in a few days we may be on the march to the frontier, we have to make the most of the time."

"He has done well, Keith, and his zeal shows that he will make a good soldier. Yes, another three days, and our messenger should return from Vienna; and the next morning, unless the reply is satisfactory, the troops will be on the move. After that, who knows?"

During the last few days, the vague rumours that had been circulating had gained strength and consistency. Every day fresh regiments arrived and encamped near the city; and there were reports that a great concentration of troops was taking place, at Halle, under the command of Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick; and another, under the Duke of Bevern, at Frankfort-on-the-Oder.

Nevertheless, the public announcement that war was declared with Austria, and that the army would march for the frontier, in three days' time, came as a sudden shock. The proclamation stated that, it having been discovered that Austria had entered into a secret confederacy with other powers to attack Prussia; and the king having, after long and fruitless negotiations, tried to obtain satisfaction from that power; no resource remained but to declare war, at once, before the confederates could combine their forces for the destruction of the kingdom.

Something like dismay was, at first, excited by the proclamation. A war with Austria was, in itself, a serious undertaking; but if the latter had powerful allies, such as Russia, France, and Saxony--and it was well known that all three looked with jealousy on the growing power of the kingdom--the position seemed well-nigh desperate.

Among the troops, however, the news was received with enthusiasm. Confident in their strength and discipline, the question of the odds that might be assembled against them in no way troubled them. The conquest of Silesia had raised the prestige of the army, and the troops felt proud that they should have the opportunity of proving their valour in an even more serious struggle.

Never was there a more brilliant assembly than that at the palace, the evening before the troops marched. All the general officers and their staffs were assembled, together with the ladies of the court, and those of the nobility and army. The king was in high good humour, and moved about the rooms, chatting freely with all.

"So you have come to see us at last, young sir," he said to Fergus. "I should scold you, but I hear that you have been utilizing your time well.

"Remember that your sword is to be used against the enemies of the country, only," and nodding, he walked on.

The Princess Amelia was the centre of a group of ladies. She was a charming princess, but at times her face bore an expression of deep melancholy; and all knew that she had never ceased to mourn the fate of the man she would have chosen, Baron Trench, who had been thrown into prison by her angry father, for his insolence in aspiring to his daughter's hand.

"You must be glad that your hard work is over, Drummond," Lindsay said, as they stood together watching the scene.

"I am glad that the drill is over," Fergus replied, "but I should have liked my work with the professor to have gone on for another six months."

"Ah, well! You will have opportunities to take it up again, when we return, after thrashing the Austrians."

"How long will that be, Lindsay?"

The latter shrugged his shoulders.

"Six months or six years; who can tell?" he said. "If it be true that Russia and France, to say nothing of Saxony, are with her, it is more likely to be years than months, and we may both come out colonels by the time it is over."

"That is, if we come out at all," Fergus said, with a smile at the other's confidence.

"Oh! Of course, there is that contingency, but it is one never worth reckoning with. At any rate, it is pretty certain that, if we do fall, it will be with odds against us; but of course, as aides-de-camp our chance is a good deal better than that of regimental officers.